Patrick walked with his friend Marek, a Polish immigrant who spoke English in chunks but laughed like a full sentence.

“You hear?” Marek asked. “Company say today will be easy. Easy day.”

Patrick snorted. “The company doesn’t know the meaning of easy.”

Marek grinned. “They know the meaning of money.”

Patrick didn’t answer. He looked at the mine entrance as it grew closer, that black mouth in the hillside that swallowed men the way the sea swallowed ships. Above it, winter trees stood like witnesses who had grown tired of testifying.

At the lamp house, Patrick checked his gear. The lamp’s flame was small and stubborn. He stared at it a moment too long, thinking about how a flame was basically a captive miracle. One breath wrong, and it died.

“Pat!” someone called. “You coming?”

He forced himself forward. One step, then another, down into the wooden throat of the earth.

The mine greeted them with its familiar dampness, its metallic tang, its slow drip-drip that sounded like a clock losing patience. The air was thick. Patrick could feel it on his tongue.

They rode down and down, the sounds of the surface thinning until the only world left was rock and timber and the scrape of boots. At the bottom, they split into teams.

Patrick’s assignment that day was in a deep section that had been mostly stable. Mostly. The word “mostly” had killed men before.

He worked with steady hands, swinging his pick, listening to the rock, to the timbers, to Marek’s muttered prayers in Polish. Between strikes, Patrick heard the mine’s breath, that subtle shift of air that made his skin prickle.

At some point, a strange stillness settled. Not quiet exactly, but something like the mine pausing to think.

Patrick looked up.

Marek wiped his forehead. “You feel that?”

Patrick nodded. “Yeah.”

The lamps flickered.

Somewhere deeper, far off, came a sound that didn’t belong to tools. It was a low thump, as if the earth had taken a fist and tested its own wall.

Men froze. Then the mine answered itself with a deeper roar.

The explosion hit like a furious god.

It wasn’t a single noise. It was a chain of violence: a crack, a boom, a rushing pressure that shoved air through tunnels like a giant’s breath, carrying dust and fire and death. The lamps went out in a blink. Darkness snapped shut like a trap.

Patrick was thrown sideways. His shoulder slammed rock. His head rang. In the black, men screamed names, screamed prayers, screamed nothing at all.

Then came the collapse.

Timbers groaned. Rock poured. The tunnel shuddered like a living thing trying to shake off fleas.

Patrick crawled instinctively, hands scraping stone, lungs choking on dust so thick it felt like swallowing cloth. Something struck his back, hard. He cried out, then bit it back because he needed air for more important things: breathing, living.

He heard Marek shouting, heard his friend’s voice break off mid-word, swallowed by the earth.

Patrick reached into darkness, fingers closing around nothing.

The collapse continued, then slowed, then stopped with a final, ugly settling sound that felt like a door being locked.

Silence came after. Not the peaceful kind. The kind that meant the mine was done screaming and had started eating.

Patrick lay still, listening to his own breath rasping. He tried to move his legs. Pain flared, but movement happened. That was good. He rolled onto his side and coughed until his throat burned.

When he sat up, he bumped his head on something low. He reached up and touched timber.

Wood.

He kept his palm there, feeling its rough grain, and realized the timber wasn’t pressing down on him. It had wedged in a way that held back the full weight of the rock. A jagged piece of wood, trapped at an angle, pinned between fallen stone and what was left of the tunnel ceiling.

A small pocket of space.

A cruel little mercy.

Patrick’s heart hammered. He felt around with trembling hands. Rock on three sides. Timber above. Behind him, the tunnel wasn’t collapsed completely, but it was sealed, packed with debris like a cork in a bottle.

He was alive.

That was the first fact.

The second fact came like ice water: he was buried.

He called out. “Hello! Hello!”

His voice bounced off rock and came back smaller. He tried again. “Is anyone there? Marek!”

No answer.

He listened, straining so hard it hurt. Nothing but drip… drip… drip.

Somewhere above, the world had exploded and kept moving without him.

Patrick’s mind tried to sprint into panic. He grabbed it by the collar. Not yet, he told himself. Panic is a luxury. Panic spends energy you cannot afford.

He checked his lamp. Dead.

He checked his pockets. Nothing useful. A bit of tobacco. A matchbook, crushed. A scrap of bread, flattened, dusted in grit. He ate it anyway, slowly, as if chewing could stretch hope.

Then he pressed his ear to the debris and shouted again, until his throat ached.

Minutes passed, or hours. Time in darkness is a liar.

At some point, faint vibrations came through the rock. Distant. Like someone knocking on a door far away.

Patrick surged up, heart leaping. “Here!” he screamed. “I’m here!”

He screamed again and again, until his voice turned raw.

The vibrations returned, then faded. Returned, then faded.

Rescue teams, his mind insisted. They were coming. They had to.

He clung to that belief like a rope in a flood.

The first day, he rationed his voice. The second day, he didn’t. He shouted at every hint of sound. He pounded rock with his fists until his knuckles split.

By the third day, his throat was so swollen it felt like he had swallowed a nail.

And then, the worst sound of all came through the debris: not rock, not timber, not men.

Silence.

Not just a pause.

A stopping.

Patrick lay with his cheek against stone, listening for the scraping of shovels, the pick of iron, the human stubbornness of rescue.

Nothing.

He tried to shout, but only a harsh croak came out. He forced air through his wrecked throat. “Please,” he rasped. “Please.”

No answer.

Later, he understood what had happened: the rescue teams had declared everyone dead after three days. That was the rule of despair. That was what a town did when it could not bear to keep hoping.

But Patrick didn’t know the rule. He only knew the result.

They stopped digging.

The mine had closed its fist around him and the world had walked away.

In the black, his mind began to do what minds do when cornered: it tried to build a coffin out of thoughts.

You are alone.

You will run out of air.

You will die and no one will find you until your bones are polite.

Patrick pressed his palms to his face. His eyes were open, but there was nothing to see. Darkness was a physical thing now, thick as felt. It seemed to press against his eyeballs, whispering, Look at it. Look how endless I am.

He remembered Nora’s face at the table. The baby’s grip. The warmth of coffee.

He remembered the mine entrance, that black mouth.

He wanted to cry, but he was afraid tears would waste water.

Because now water was the only currency that mattered.

He crawled along the small space, hands exploring rock and wood. His fingers found dampness. A trickle. Not much, but enough that the stone was wet.

He pressed his mouth to it and drank like a starving animal.

The water tasted of earth and metal. It was cold. It was alive.

Patrick whispered, “Thank you,” to the rock, to God, to anything that might be listening.

Food was a different problem.

The first few days, hunger was a dull ache. Then it sharpened into something that felt like teeth inside his belly. His body began eating itself in quiet protest.

He searched his pockets again. Tobacco. A crushed match. Dust.

He tried to chew tobacco, to trick his stomach. It worked for an hour, then the hunger came back angrier.

By day five or six, his thoughts became strange. He caught himself imagining bread as if it were a person. He caught himself smelling stew that wasn’t there.

He stayed still as much as he could to conserve air, to conserve strength. The darkness made sleep difficult because sleep required surrender, and surrender felt too close to dying.

Sometimes he drifted off anyway, and the mine visited him in dreams: ceilings collapsing, Marek’s voice cut off, Nora calling his name from far away. He woke gasping, heart racing, hands clawing at rock.

He began to talk to himself, not because he was losing his mind, but because silence felt like it was trying to erase him.

“My name is Patrick O’Brien,” he whispered. “I’m twenty-nine. I live on Water Street. My wife is Nora. My daughter is…” He said her name like a spell. “I am not dead.”

He repeated it. Again and again.

The hardest battle was not with hunger or thirst.

It was with the idea that the world had already buried him in its mind.

Patrick could almost hear the town’s voices: All gone. God help us. It’s over.

Over.

The word tasted like dirt.

“No,” he told the dark. “Not yet.”

By the seventh day, his body was weakening. He stood less. He moved slower. His mouth was dry more often. The trickle of water seemed smaller, or maybe he was drinking more because his body was desperate.

His boots sat near his knees, heavy shapes in the black. He touched them, feeling the leather.

He remembered his mother saying, when they were poor, that leather was “food in disguise” if you were hungry enough. He’d laughed then, a boy with a full belly.

Now, he didn’t laugh.

He took one boot and worked at the edge with his fingers, tearing a strip of leather. It was tough, stubborn. He chewed it. His jaw ached. The leather tasted like salt, like sweat, like every mile he’d walked to the mine.

He swallowed slowly, forcing it down, and his stomach clenched in offended confusion, then quieted slightly, as if it had accepted the bargain.

Patrick ate another strip.

He whispered, “Sorry,” to his boot, as if it were a friend he was sacrificing. “I need you to keep me here.”

Days blurred.

He counted them by routine: drink when he could, chew leather when hunger clawed too hard, rest, listen, whisper his name, whisper Nora’s name, refuse to let darkness turn him into a story with an ending.

Sometimes he thought he heard digging again. He would shoot upright, heart lurching, and shout until his throat bled, only to realize it was his own blood roaring in his ears, or a rock shifting, or the mine settling as it always did.

But on what he believed was the eleventh day, something changed.

At first it was so faint he thought it was another lie. A vibration, a rhythm. Not random settling, not the groan of timber.

A scrape. A tap. Another scrape.

Patrick froze, afraid to breathe too loud.

Then it came again, stronger.

His heart slammed against his ribs like it was trying to break out and run toward the sound.

He crawled to the debris, pressed his ear to it, and heard something impossible: human voices, muffled but real. The sound of men working, cursing softly, breathing hard.

Patrick opened his mouth to shout and realized his throat was nearly gone. He forced the sound anyway, a ragged animal noise.

“Here!” he rasped. “Here!”

He pounded the rock with his fist.

The voices stopped.

A pause, then a shout from the other side, faint but clear enough to slice through the darkness like a blade.

“Did you hear that?”

Patrick cried, a sound that came out half sob, half cough. He slammed his fist again.

Tools struck rock. Faster now. Urgent.

Patrick’s body trembled so violently he couldn’t control it. He laughed, then coughed, then laughed again, because the sound of digging was the most beautiful music he had ever heard.

The rescue team had returned on the eleventh day, not with hope, but with grim duty. They were looking for bodies.

Instead, they found a man who had refused to become one.

Rock shifted. A small hole opened. A sliver of light pierced the darkness.

Patrick screamed.

Not in joy.

In pain.

The light stabbed his eyes like a spear. After eleven days of absolute dark, even a candle would have been cruel. This was brighter. The world poured into him too fast.

“Easy!” a voice called. “Easy, for God’s sake!”

Hands reached in, rough hands, careful hands. Someone’s fingers brushed Patrick’s cheek and he flinched, not from fear of touch, but from the overwhelming shock of being touched by the living.

“He’s alive,” someone said, disbelief wrapped around the words like bandage gauze.

“Sweet Jesus, he’s alive.”

They widened the opening, working quickly, and Patrick felt air move, fresh air that smelled like sweat and cold and the outside world.

They pulled him gently, inch by inch, out of the pocket that had been his tomb and his shelter.

His body protested. His muscles cramped. His bones felt like they had forgotten how to be bones.

When they finally lifted him into the open tunnel, he tried to speak, tried to say thank you, tried to say I’m here, I’m here, but only a hoarse whisper came.

He blinked at the light and saw only blur, white and burning. Shapes moved around him, men’s faces swimming in brightness.

“Don’t look,” someone said. “Close his eyes.”

They covered him, carried him up, up, up through the mine that had tried to keep him forever. Every jolt made him gasp. Every breath tasted like coal and resurrection.

When he surfaced into the winter air, the cold hit him like a slap, and he loved it anyway. Cold meant sky existed. Cold meant the world had not ended.

People gathered, shouting, crying, praying. Women pressed hands to mouths. Men took off hats like they were in church.

Patrick heard someone sobbing and realized it was him.

They brought him to a small room, wrapped him in blankets, poured warm broth into him in careful spoonfuls. Doctors hovered, murmuring words that sounded far away.

Patrick lay staring into a haze. His eyes wouldn’t focus. The light seemed too big. He tried to blink tears away, but the tears didn’t help.

A doctor leaned close. “Patrick,” the man said gently, “can you see me?”

Patrick squinted. He saw a pale shape. He heard the concern in the voice. “I… I see light,” Patrick croaked.

The doctor’s jaw tightened. “Your eyes were in complete darkness a long time. They’ve been damaged. We’ll do what we can.”

“What does that mean?” Nora’s voice cut in.

Patrick turned his head toward the sound. He couldn’t see her clearly, but he knew her voice the way a sailor knows the direction of home.

Nora grabbed his hand. Her fingers were warm, shaking. “Pat,” she whispered, breaking. “Pat, I thought…”

Patrick tried to lift his hand to her face, but his arm felt like it belonged to someone else.

“I didn’t,” he rasped. “I didn’t die.”

Nora sobbed, pressing her forehead to his knuckles like she was anchoring him to the world.

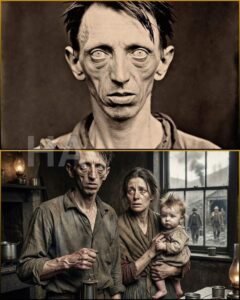

Two days later, a photographer took a portrait.

Patrick sat stiffly, thinner already, his cheeks hollowed as if the mine had sucked the flesh right off his bones. He held a piece of wood in his hands, the same jagged timber that had wedged into falling rock and saved him from being crushed.

He held it like a relic and like a weapon.

His eyes, damaged by darkness, looked strange in the light. He tried to stare straight ahead, but the world swam.

The photograph caught him not as a hero, not as a ghost, but as something more unsettling: a man who had returned from a place most people didn’t come back from, and who carried that place behind his eyes.

When the company men came, Patrick expected sympathy.

What he got was paperwork and a check.

A supervisor in a clean coat cleared his throat. “Patrick, we’re… glad you made it,” he said, as if describing a lucky horse. “The company is prepared to offer you fifty dollars. And of course, the medical care. It’s… generous, considering circumstances.”

Patrick stared at the man’s blurry outline. “Fifty,” he repeated.

“Yes,” the supervisor said, relieved Patrick understood numbers.

Patrick’s throat tightened, not from injury, but from rage so sharp it felt like a new kind of pain.

“How much for eleven days?” Patrick whispered. His voice was still rough, but the words landed like stones. “How much for being buried alive?”

The supervisor shifted uncomfortably. “Patrick, no one could have predicted…”

“Three hundred and sixty-two men died,” Patrick said, the number coming out like a curse. “Dead at once. And I…” He swallowed. “I lived. I drank water from rock. I ate my boot. I listened to you stop digging after three days.”

The supervisor’s face went stiff. “That was a decision made by rescue leadership based on available information.”

Patrick laughed once, bitter. “Available information,” he repeated. Then he held up the check, the paper trembling in his fingers. “You call this luck?”

The supervisor’s voice hardened. “You survived. You should be grateful.”

Patrick’s eyes burned. “I’d rather have died,” he said quietly, and the room went still, “than take fifty dollars as pay for eleven days in a grave you built.”

Nora gasped softly. The supervisor flushed.

“Take it or don’t,” the company man snapped, pride wounded. “But the matter is settled.”

He left the check anyway.

Patrick stared at it long after the door closed, as if paper could suddenly turn into an apology.

He didn’t go back underground. He couldn’t.

At first he told himself he would. He pictured himself descending again, proving he was still a man. He imagined the town’s respect, the company’s nod, the way miners looked at each other when one of them didn’t break.

But then night came.

And with night came the tunnel.

In his bed, Patrick would close his eyes and feel rock above him. He would feel the air thinning. He would hear Marek’s cut-off shout. He would wake gasping, clawing at the sheets like they were debris.

If Nora blew out the candle, Patrick jolted upright, panicked, heart sprinting.

“I can’t,” he whispered, trembling. “Not dark. Not dark.”

So Nora left a lamp burning. A small nightlight before people used the word “nightlight.” A flame that stood guard between Patrick and the mine that still waited inside him.

He found work above ground for a while, eighteen months of hauling, sorting, doing jobs that kept him under the open sky. The company tolerated him because his story had made headlines, because he was a living reminder that the mine had a conscience problem.

But stories fade. The company’s patience did too.

One day, a foreman called him in. “Patrick,” the man said, not unkindly, “they say your productivity’s down.”

Patrick stared at him. “My productivity,” he repeated, amazed.

The foreman rubbed his neck. “Orders from above. They say you move slow. They say you get… distracted.”

Patrick thought of the way his hands shook when he heard loud bangs. Of the way his eyes, still damaged, struggled with glare and shadow. Of the way his stomach turned when he walked near the mine entrance.

“My productivity is down,” he said carefully, “because your tunnel buried me for eleven days.”

The foreman’s face tightened. “Accident happened,” he said, rehearsed words sliding out like coins. “Company says injuries from that day aren’t their responsibility. You lived. It’s finished.”

Finished.

There was that word again.

Patrick left the office without yelling. He didn’t have enough voice left in him for that kind of fight. He walked home under an open sky and felt the strange loneliness of being alive in a town that had already moved on.

He tried other work. Small jobs. Fixing fences. Delivering coal above ground. Anything that kept him out of tight spaces.

But even open fields couldn’t fully erase the mine’s shadow.

Years passed. The baby grew into a girl who learned early not to slam doors, because loud bangs made her father’s face go pale. Nora learned to read Patrick’s breathing the way some wives read weather. If it got shallow, she knew the mine was visiting him again.

Patrick lived fifty-six more years with the aftermath of eleven days.

That was the cruel math of survival.

He didn’t die in the tunnel, but part of him stayed there, pressed under rock, counting drips of water, chewing leather, refusing the dark’s invitation to quit.

In 1950, when Patrick was old enough that his hair had gone mostly white, a young man came to his house with a notebook. The boy said he was collecting stories, testimony, truth that towns tried to bury.

Patrick almost refused.

He was tired of being “the lucky one.” Tired of people saying, “At least you lived,” as if living was automatically a blessing.

But his grandson, Sean, sat on the floor nearby, listening with wide eyes, and Patrick felt something shift. Not hope exactly. Responsibility.

He cleared his throat and spoke slowly, each word shaped like it cost him something.

“I survived eleven days in the collapsed mine,” Patrick said. “I drank seep water and ate my shoe leather. Rescue teams gave up after three days. I refused to die.”

The young man’s pencil moved quickly.

Patrick continued, voice rougher now, not from age, but from memory. “The company gave me fifty dollars for surviving. I spent fifty-six years with nightmares, panic, ruined sight. They called me lucky.”

He paused, eyes staring past the room.

“I survived,” he said, and his voice softened into something that sounded like grief wearing plain clothes. “But I never stopped being buried. A part of me stayed in that tunnel for fifty-six years. Survival isn’t freedom. It’s a long burial.”

The boy’s pencil stopped. Even Sean stopped breathing for a moment, as if the room itself was listening.

Patrick reached for the lamp on the table, the one that always stayed lit when the sun went down. His fingers brushed the warm glass.

“At night,” he said quietly, “I keep the light on. I’m eighty-five and I keep a light on because darkness remembers me.”

Sean didn’t understand it fully then.

He understood later.

In 1963, Patrick died at eighty-five.

He died in a bed with a lamp burning nearby, because the dark was still too heavy to trust. Nora had passed before him, and the house was quieter than it used to be, but the lamp remained, faithful as breath.

On the day of the funeral, Sean stood by the grave holding the old photograph, the one taken in 1907. Patrick’s hollow face stared out from the image like a man returning from the underworld. In his hands was the jagged piece of wood that had made a pocket of air, a small defiance against stone.

Sean ran his thumb along the photo’s edge.

People said kind things at the graveside. They said, “He was strong.” They said, “He was lucky.” They said, “God had a plan.”

Sean listened politely, but inside him something burned.

Because he remembered the way Patrick’s voice had sounded in 1950 when he said I never stopped being buried.

After everyone left, Sean stayed a while. The winter air was sharp. The sky was open.

He placed the photograph carefully back into his coat and pulled something else out: a small lamp, simple, plain. Not fancy. Just a little light.

He set it on the ground near the fresh earth.

A foolish gesture, maybe.

But Sean wasn’t doing it for the dead. He was doing it for the living part of his grandfather that had stayed underground for fifty-six years.

He imagined Patrick in the tunnel, eleven days in pitch black, whispering his own name so the darkness couldn’t erase it. He imagined the way Patrick must have flinched when the first light appeared, not because he didn’t want rescue, but because even salvation can hurt when it comes too suddenly.

Sean lit the lamp.

The flame trembled, then steadied.

He spoke out loud, voice quiet, the way you talk in churches and mines. “You’re not there anymore,” he said, not sure who he was addressing. “You’re not buried.”

The wind moved through the trees, and for a moment it sounded like distant digging.

Sean stood, wiped his eyes with the back of his hand, and looked toward the mine in the far hills, invisible from here but present in the town’s bones.

He understood something then that Patrick had lived in his body for decades:

Survival is not a clean ending.

Survival is not a parade.

Sometimes survival is a man waking up every night for fifty-six years, reaching for light because darkness still has teeth.

But Sean also understood something else, something Patrick hadn’t been able to fully feel while he was busy fighting the tunnel inside his head:

A story can be a rescue team that comes late, but comes anyway.

So Sean carried the photograph home. He kept Patrick’s testimony. He told the story to his own children, not as a tale of luck, but as a warning and a promise: that men are not disposable, that suffering cannot be paid off with fifty dollars and a shrug, that the earth remembers everything, and so should we.

And every night, before bed, Sean left a small lamp burning in the hallway.

Not because he was afraid of the dark.

But because he refused to let the dark pretend it had won.

Sean didn’t keep the lamp lit because he feared the night.

He kept it lit because his grandfather had earned the right to never be alone in the dark again.

Years later, when strangers asked about the old portrait on the wall, Sean would point to the jagged timber in Patrick’s hands and say, “That piece of wood held back the mountain. But what truly saved him was that he refused to accept the world’s decision for him.”

And whenever the room went quiet, Sean would add, almost like a prayer that didn’t need a church:

“Survival isn’t the same as being saved. But telling the truth is how we bring someone all the way home.”

The lamp stayed on.

Not as fear.

As remembrance.

As justice in miniature.

As a small, steady refusal to let any human life be written off as ‘lucky’ and forgotten.

THE END

News

The billionaire dismissed the nanny without explanation—until his daughter spoke up and revealed a truth that left him stunned…..

Laura’s throat tightened, but she kept her voice level. “May I ask why?” she said, because even dignity deserved an…

I HAVE BEEN SLEEPING WITH OUR GATE MAN FOR 3 GOOD YEARS AND MY HUSBAND KNEW.

The first time I said it out loud, the words tasted like pennies and smoke. It was in a conference…

A single schoolteacher adopted two orphaned brothers. When they grew up to become pilots, their biological mother returned with 10 million pesos, hoping to “pay a fee” to take them back…

The departures hall at Los Angeles International Airport always sounded like a thousand lives humming at once. Wheels whispered over…

My grandpa saw me walking while holding my newborn baby and said ” I gave you a car, right?”…

The cold that morning wasn’t the cute, Hallmark kind of winter cold. It was the kind that turned your eyelashes…

He Visited the Hospital Without Telling Anyone — What This Millionaire Witnessed Changed Everything

Alexander Reynolds walked into the hospital believing he still had time. Time to fix things. Time to protect the people…

The Billionaire Was About To Sign Bankruptcy Papers When A Waitress Spotted A Crucial Mistake

The pen hovered a breath above the paper. Across the polished conference table, the billionaire’s hand shook so badly the…

End of content

No more pages to load