It began with eight words that felt like a verdict.

“Pick someone else. I’ve been returned three times.”

Lucas Hail had built his life around certainty: algorithms that predicted markets, contracts written in steel, a calendar so tight it could slice the air. The noise of his world—investors, press releases, the steady hum of his penthouse above Central Park—had taught him to answer everything with a plan. He was not prepared, not for a child who said no with the calm of weather.

He had not told anyone he was coming. The city that morning was a pattern he recognized by habit: taxi horns, coffee steam, newsfeeds full of numbers. He left the suit in the closet, traded the driver and the town car for a subway token and a hoodie he had not worn since he was twenty and broke in the Bronx. He walked into St. Catherine’s Family and Adoption Center with the kind of anonymity that felt unfamiliar and oddly clean.

“Mr. Hail, we weren’t expecting—” the receptionist began.

“Just Lucas,” he interrupted, lowering his voice. “I’m here to see Maya Rivera.”

Dr. Nisha Patel led him to the room where children’s drawings lined the walls—homes with doors permanently open, suns with too many rays, crayon rainbows. The first time he saw Maya the world narrowed to the frame of her wheelchair, angled toward the window, a turtle plush folded in her lap like a small, solemn companion. Her curls made a halo, and the rims of the chair’s wheels were wrapped in galaxy tape.

She didn’t look up when he spoke. “Hi, Maya. I’m Lucas.”

She studied his sneakers, then his face, the way someone would test a material to see if it would withstand pressure. “They told me you build things,” she said. “Apps and robots or something.”

“I build ways for people to connect,” he offered.

She shrugged as if connections were a weather pattern. “People always connect until they leave.”

Something in his chest tightened. He had come to fix a person, or perhaps to fix himself; guilt from his sister Anna’s death still tasted like rust in his mouth. He knelt beside the wheelchair because the gap between adult world and child world felt too wide to bridge standing. “Do you mind if I sit here for a bit?”

She shrugged once. “I’m easy to push, but hard to keep.”

Dr. Patel, watching, murmured, “She doesn’t say much to most people.”

Maya’s voice was small but direct. “Pick someone else. I’ve been returned three times. Once because I cried too loud. Once because the mom said I reminded her of her own kid who died. The last one said she was tired.”

Lucas’s throat closed around a sound that was almost a laugh and almost a sob. “I don’t get tired easy,” he said.

“You will,” she answered without accusation. “They all do.”

He tried to smile but his vision blurred. She hugged her turtle and said, “I don’t want you to get tired.”

“I’m sorry,” he said, which felt too small for the weight of her truth.

“You didn’t do anything,” she said, surprising him with the kindness in her dismissal. “I just don’t want anyone to promise they’ll stay when they won’t.”

They talked for an hour that was supposed to be fifteen minutes. They spoke about turtles (they stay), about jazz on night nurses’ radios, about clouds that look like continents. Maya drew a stick figure and a wheelchair under a crooked sun and pushed the paper toward him. “You can take it,” she said, “so you don’t forget what I look like when you change your mind.”

He folded the crayon drawing into his pocket like a relic. “I’m coming back,” he promised.

She didn’t answer. The sunlight pooled on her knees. “People always can,” she murmured. “It’s the staying that’s hard.”

He left the center with the city’s roar feeling new and thin. For the first time in years he was not performing; he was listening. He read Dr. Patel’s medical notes that night—spina bifida, therapy schedules, hospital visits—but the reports couldn’t capture what living with a child like Maya felt like: the small, defensive rituals, the need to test the world to learn if it could be trusted.

He came back the next week in the same hoodie, then again and again. He learned to fold Maya’s therapy brace, to adjust the wheelchair harness, to distract her when the physical therapy made her eyes water. He brought two bags of plantain chips—both kinds—and remembers she noted, almost approvingly, that he had remembered the small things. She liked painting when no one watched. She liked turtles because “they stay.” She called him out when he tried to fix something that wasn’t broken. “Maybe you’ll stop trying to fix things that aren’t broken,” she said once, and he laughed because she had caught him bare.

They began to weave a private rhythm. Saturday outings—an hour in Central Park, a saxophonist playing by Bethesda, ice cream cones and the awkward moment when a pigeon startled them and her chair tipped on a curb. She froze and the world narrowed to the pivot of a wheel and the steadying of hands. “You’re okay. You’re safe,” he said, with the reflex of an adult offering shelter.

“Don’t say that word,” she whispered, near panic. “Everyone says that before they go.”

He heard it then, the brittle scaffolding beneath many promises, and he swallowed the word. “No more promises,” he said. “Just ice cream.” She took the cone.

Lucas began to re-calculate his priorities with the same ruthless clarity he had once reserved for boardrooms. He wrote an email to his board—indefinite leave. He bought a brownstone in Brooklyn Heights with chipped steps and a backyard stubborn with ivy. He told the contractors to build it as though someone he loved would live there: wider doorways, ramps, an elevator chair. He read, he listened, he learned. Dr. Patel warned him that high-profile applicants often faced extra scrutiny. “They’ll test you to see if you mean it,” a lawyer told him.

“Good,” he said. “They should.”

The city saw it differently. Photos leaked, cameras lurked, and the headlines called it salvation theater. The internet labeled motives and sold judgment with a swipe. Reporters camped outside St. Catherine’s. People questioned whether a billionaire could really give what a child like Maya needed. Maya saw the headlines. “Are you famous?” she asked one evening.

“Yes,” he said. “I used to be.”

“Used to be?” she said. The kindest possible truth. He stopped worrying about optics. He stopped performing.

There was a day when the process almost failed—not by his fault but by the bureaucracy and fear that follows children with complicated pasts. A former foster family filed an objection, calling Maya unstable, too difficult, manipulative. They wanted a judge to decide if she should stay in the fold that Lucas hoped to make permanent. Lucas thought he had learned to be brave in boardrooms; that was different. This time his nerves were raw for a different reason. The fear was of failing a child who had already been failed.

He drove to the courthouse in silence. Maya sat beside Dr. Patel with her turtle in her lap, wearing a red sweater Lucas had given her the first week he took her to a park. The courtroom smelled faintly of paper and stale air. When it was his turn to speak he did not offer polished rhetoric. He climbed the stand and looked at the people who had come to tell his motives.

“I’m not here because of guilt or headlines,” he said, his voice steadying into something he had not expected to find. “I’m here because a six-year-old girl taught me what love looks like if it refuses to quit. You want to know my motive? It’s not charity. It’s not redemption. It’s staying.”

He told stories—about the ice cream cone and the pigeon, about a whiteboard he had brought for days when words were heavy, about sign language lessons learned with clumsy hands and laughter. He spoke about Anna, about how grief had remade him into someone who could measure life in minutes rather than profit margins. He did not hide the part of himself that was broken; he offered it like a map.

At the end of the hearing the judge said she needed time to deliberate. Lucas waited in a corridor that smelled like old coffee and rain. Maya wheeled up and said what she often said after one of his speeches. “You talked a lot.”

“I do that when I’m nervous,” he admitted.

“You didn’t sound nervous,” she observed.

“I was,” he said. “You make me brave.”

The decision came at dawn, a text from Dr. Patel that trembled like a small victory. The judge approved the placement. Lucas sat on the edge of his bed and stared at the wet city outside as sunlight threaded through the clouds. He whispered as if to someone who had guided him here, “We did it, Maya. We finally stayed.”

On moving day the city felt softer, as if every honk and rush had been turned down a notch. Maya rolled down the brownstone ramp wearing a denim jacket over a yellow dress, the turtle perched like a talisman. She looked around with a mixture of suspicion and cautious approval.

“It looks old,” she said.

“Old things have stories,” he replied, and it was true. The brownstone had been renovated with intention, not for show. There was a place for her wheelchair by the bed and a painting she’d once drawn framed on the desk—a secret photo from Central Park tucked into the frame. “You kept this,” she said.

“I keep everything that matters,” he answered.

The first months were a study in ordinary tenderness. Nurses came in the mornings. Therapists took schedules and taught him how to hold a pill bottle like a valet holds a key—deliberate, careful, respect embedded. Maya made pancakes with too much syrup; he burned a few and laughed about it. She taught him when to speak and when to be silent. She taught him how to read her without words, the flicker of a brow that meant she was worried, the way her fingers worried at the hem of a shirt when she needed reassurance. He taught her how to trust a calendar again, the gentle constancy of a man who came home because he wanted to, not because a camera asked him to.

Maya began to open in small ways. She attended art classes, shy at first, then proud enough to hand him a paper streaked with color and say, “This is what quiet looks like.” She took up wheelchair basketball with Marvin, the coach who bellowed encouragement like a second dad. Neighbors stopped staring and started asking about plants in the backyard. Grace from the diner brought soup.

One autumn evening, with wind tossing leaves like confetti, they sat in the garden and Maya said, “Do you still miss her?” She meant Anna. He did—still—less like an empty place and more like a room he visited sometimes with a bouquet.

“Yes,” he said, “but it doesn’t hurt like before.”

“Maybe that’s what love does,” she said, looking small and very old at the same time. “It stays, even when it changes shape.”

She leaned her head against his arm and fell asleep as he watched the sky. He realized then that staying was not an act of endurance alone; it was a decision to accept small, quiet transformations. It was the daily choice to be present when it would be easier to walk away.

Spring came a year later with daffodils nodding in the garden. Maya’s painting—galaxy-wheeled turtle, two figures, a starry field—won a place in a community art show. The title read simply: Staying. When the applause broke around her, she handed him a folded paper: her “new resume.” Under the creases, in uneven handwriting, were three sentences—“I can laugh again. I can love. I can stay.” He added one more in his head and in his voice when he hugged her: “You taught me how to stay too.”

On quiet nights, when New York hummed beyond the window like an engine waiting, they kept to small rituals: pancakes on Sundays, garden club on Tuesdays, drawing on Thursdays. Sometimes he would find a note taped to his office door—purple crayon handwriting reading, You forgot to sign my turtle drawing. Underneath, in smaller letters, People who stay should sign things.

He signed the corner of the sky.

There was no miracle, no sweeping redemption staged for the cameras. What changed was pedestrian, stubborn, and profound: a billionaire learned to be ordinary; a little girl learned to allow a single adult to be permanent. They taught each other how to endure the small defeats and to accept that staying sometimes means simply being present on days when presence looks like silence.

When asked later, in quieter moments, what had made him choose to stay, Lucas would touch the faded crayon drawing in his wallet and say, “She said she’d been returned three times. I heard her and I understood that some things, the hardest things, are not fixed by money. They’re fixed by someone deciding to be there, again and again.”

Maya would answer with the practical certainty she’d always carried. “Turtles don’t fly away,” she would say. “They stay. People should try that.”

They did.

News

A Billionaire Found His Grandson Living in a Shelter — “Where Is Your $3 Million Trust Fund?”

Malcolm Hayes kept his grief polished the way some men kept their watches. Shined. Quiet. Always visible if you knew…

Millionaire come home to see the new maid’s son Doing the Unthinkable, after “18 Doctors Failed.

The surgeon’s pen tapped the consent form the way a metronome taps out a countdown. “You’re signing today, sir,” he…

Your Mother Is Alive, I Saw Her in the Dump!, The Poor Boy Shouted to the Millionaire,

Before the city could breathe again, it had to learn how to listen. For forty-eight hours, the name Margaret Hail…

A Homeless Black Girl Saved a Dying Man Unaware he’s a Millionaire What he Did Next Shocked Everyone

The air above the scrapyard shimmered like a warning. Heat rose off the twisted ribs of metal and broken glass,…

“Sir, your son gave me this shirt yesterday” — What the boy revealed next shocked the millionaire

The wind that afternoon felt like it had been carrying the same sentence for years and still didn’t know where…

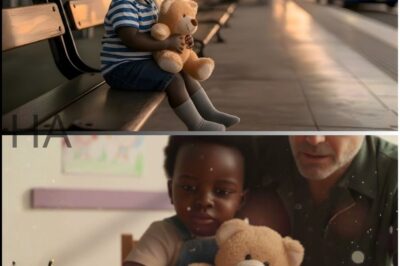

Dad Abandoned his disabled son At Bus Stop- Millionaire found him what he Did Next Will Shock You!

The sunset burned against the glass walls of Edge Hill Bus Terminal, turning every metal edge into a knife of…

End of content

No more pages to load