“Moon, what the hell are you doing?” Kincaid demanded. He had noticed the heavier grenade. “Those aren’t—”

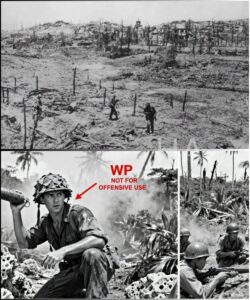

“They won’t bounce,” Harold said. He didn’t need to explain the rest; the calculus was already happening inside him. The M15 was heavier and the phosphorus burned at a temperature that could, if it went inside, make the bunker a furnace and smoke the gunner out. The regulations meant something in the classroom. On Biak, the regulations were getting men killed.

“Put it back,” Kincaid said.

Harold did not. He thumbed the pin, felt the sudden, small, precise action that separated intent from consequence, and threw.

The heavier grenade arced as he expected: a cleaner trajectory, a flatter flight, a punctuation that matched the angle of the firing slit. It hit the lip and dropped in. Harold counted under his breath—one, two, three—and then a white fire and smoke rolled out, scorching the leaves, a smell like metal and burning cloth. The machine gun snapped and then stilled.

The reaction around him was instantaneous: shouts, a wild rush of movement as men realized what had happened. Harold let out a breath he did not know he’d been holding, and Kincaid, who was no fool but had been schooled in manuals and common procedure, said, “Goddamn it.”

They kept going. Another M15, another perfect entry. Another stoppage. By noon Harold had cleared, single-handedly as far as anyone could tell, eight bunkers. Men who had been cursing and bleeding now moved forward in a jittery, stunned line. The company advanced four hundred yards, perhaps the fastest progress they had made since landing.

Word spread. It always does in war—the rumor that something odd works, the gossip of foxholes and mess tents, the whisper that a farm kid had used smoke grenades like weapons and had not only lived but helped bring men home. Captain James Winters, Harold’s company commander and a man used to neat doctrine and the comfort of protocol, pulled Harold aside later in the day.

“Private Moon,” Winters said, his voice low and brittle with that nervous laugh officers have when the rules bend, “you realize those—those aren’t for offensive use.”

Harold met him with the simple honesty bred of a life where things had to be said plainly. “Yes, sir.” He looked down at the mud on his boots, at the serrated cut of blood on his palm. “They won’t bounce. The Mark 2s keep slippin’ off the coral. I throw where I can get a straight shot in, wait the four seconds on the fuse, take cover. Ain’t killed a soul on our side with it.”

Winters’ jaw worked. He had orders. He had field manuals and a career and the knowledge that men would look to him if this was a trick of luck and not a tactic. He also had the faces of the men he commanded—smoky, exhausted, alive—and that tilted something in him.

“If this comes down from higher,” Winters said finally, “and you get hauled up for violating ordinance—”

“Then court-marshal me after we take this island, sir,” Harold replied.

Winters stared at him, and in that look was the weight of a man who must choose between being rigid and being human. He closed his mouth. “I didn’t see anything,” he said. “But if you get yourself killed doing this—don’t expect me to write to your mother.”

Harold laughed then, a short, dry sound. “Fair enough.”

The reckoning came sooner than they expected. Lieutenant Colonel Alexander McNab called the officers together at battalion headquarters two days later. The tent smelled of fatigues and stale paper. Maps lay scattershot across the table. Captain Winters laid out the company’s after-action report: twenty bunkers cleared in one day, nearly a mile of advance, and no friendly casualties in those assaults. Major Robert Thornton, the battalion weapons officer, was blunt and furious.

“This is insanity,” Thornton snapped. He had the slow, precise rage of a man trained to hold systems together. “You used white phosphorus offensively in confined spaces. That’s—Do you understand what that does to human tissue? Regulations exist to prevent this.”

McNab listened, watchful, then called Harold in. The farm boy from Iowa stood barefoot in dust and mud while men with maps and ribbons circled him like a rare specimen. He explained in the same plain way he spoke about corn and soybeans—this grenade didn’t bounce; it entered the slit; the phosphorus did the rest.

Thornton’s face angled like a man who had swallowed something terrible. “Two days’ success doesn’t equal validation,” he said. “A private’s ingenuity might save men—or get us all condemned.” He was thinking not of numbers but of the broader implications: treaties, regulations, the horror of something that burned through skin.

McNab, who wore command like an old coat and was tired of seeing men die in ways that made no sense, had Harold demonstrate the throwing technique on an abandoned bunker half a mile away. He watched the grenade’s arc and the column of molten white phosphorus that filled the dark interior. He watched, dispassionately at first, then with a quickened breath as the logic of the moment rearranged what doctrine had insisted for months.

“Major,” he said, finally, when the men had returned to the tent and the maps lay quiet again, “I don’t like it. But I like men who come back more.”

“Sir,” Thornton protested. “This violates Ordinance Department regulations.”

“Then tell them that in Washington,” McNab said. “We have an island to take.”

Authorization, when it came, was messy and ambiguous. McNab didn’t claim to have rewritten doctrine; he issued an order that at once recognized reality and managed the paperwork around it: white phosphorus for “special employment” cleared for bunker assault under specific conditions. It was bureaucratic fudge, but it was also a command decision that sent more men home alive.

Harold, who had been promoted to squad leader by virtue of results, taught his squad the simple rules: identify the opening, calculate the angle, throw the heavier M15, take cover for the four-second fuse, and always, always check who is between you and the blast. It was not complicated, but it was precise. It demanded patience and judgment and a cold, honest assessment of when the odds favored a throw and when they did not.

The statistics that came back from Biak were brutal but beautiful in their charity: before Moon’s technique, they were expending an average of forty-seven fragmentation grenades per bunker. After, they used an average of two to three M15s per bunker. Casualties dropped from 3.2 per bunker to under one. The battalion’s after-action reports were careful not to say “Harold Moon,” but they could not help the arithmetic.

War stories have a way of moving beyond the facts into legend. In the dark hours, around smoldering cigarettes, men told the tale of the farm kid who had asked whether regulations were killing his friends and had then thrown his weighty doubt at a coral wall and made it work. Some veterans in later reunions would mutter that Moon had risked being accused of chemical warfare. Others would say he had simply stopped the killing with what he had. The argument lived on in pubs and mess halls and in the diaries of men who’d been there.

The Japanese, for their part, did not write diaries that betrayed confusion. They did not need to. After the battle, captured documents spoke plainly of a new American tactic: “burning fire that enters our caves, that makes the air lethal,” an officer wrote. “It forces evacuation or death.”

The decisive fight came on June 2nd at Mokmer airfield. The Japanese had ringed the perimeter with sixty-eight bunkers. They had designed overlapping fields of fire so that attackers would find no safe approach. The staff officers predicted three days to breach the defenses; the men on the ground, who had already paid those predictions in blood, did the math differently. Harold’s squad had trained others. The technique had diffused like a rumor. Men who had once accepted doctrine without question now carried heavier grenades in pouches and a new small print in their brains: think, aim, do not waste.

At zero-six-hundred, they went across the open ground. Machine-gun fire carved the morning. Men fell in shell craters and in the silt; medics ran on cries and lost their own. Harold signaled his team and moved in bounds, suppression from a team and forward movement from another. The first bunker was a straightforward arc. The second required him to half stand in view to get the right angle, bullets stinging his back like a dozen small, angry wasps. For the third, he had to throw two M15s in quick succession—one in the main slit, the other into a ventilation port. The bunker filled with white heat and choking smoke; the machine gun fell silent.

Across the field, other squads used the same method. A defense that had been invulnerable for months fell into anatomical collapse. By midafternoon the perimeter was breached. American forces cleared the airfield by thirteen-hundred hours—eight hours, not three days. The cost was terrible in human terms—still lives lost—but far less than the staff officers’ original numbers had predicted. The math was, again, cruel and kind.

After the war, the world tried to tidy its uncomfortable features. Regulations were revised in print but not in spirit. Field manuals appended caveats about using smoke grenades in extreme conditions. The Ordnance Department, wary of precedent and litigation, never wrote Harold Moon’s name next to those amendments. The silver star citation he received used the soothing language of bureaucracy: “for gallantry in action and innovative employment of available resources.” It was accurate in the way a photograph is accurate: it recorded light without telling the story behind the eyes.

Harold returned to Grundy County as the war’s heavy quiet settled on him like wool. He married his high school sweetheart, Mary, whose hands smelled of flour and the days when she’d been waiting for letters with a patient, small hope. They raised three children. He took over his father’s dairy farm and learned again the intimate habits of cows and seasons. He went to church on Sundays and shucked corn in the rows and repaired fences with the same exactness he’d once used to estimate a grenade’s trajectory.

Veterans called and wanted him at reunions. Papers asked for interviews. He declined. Not out of shame—Harold did not appear to keep such things close as a penumbral sorrow—but because he had seen what being the center of attention did to men who were trying only to live after war. He had watched others find a voice and use it like a fist. He wanted nothing to do with that noise. He wanted his children to know him as a father who could mend a milking machine and dig a well.

Yet closure is a social thing, not just an interior habit, and years have a way of making people search for small reconciliations. At a 41st Division reunion in Des Moines in 1982, an elderly man with a slow step came up to Harold in the hall between the coffee urn and the registration table. The man’s eyes were ringed with tiredness and gratitude.

“My father was Captain James Winters,” he said, without preamble. “He died in ’79. Before he passed, he asked me to find you. Wanted me to tell you something.”

Harold listened while the man spoke, while he said that his father had kept a list of every man in Easy Company who had come home. He had calculated, in the thin arithmetic of a commander, that had Moon’s technique not been used, forty-seven men who had returned would have died on Byak. “He kept saying,” the son told Harold, “that you saved his company. That you were the bravest man he ever commanded.”

Harold wanted to say something small and proper. He put a hand on the man’s shoulder and felt the skin like a thing he recognized. “He was a good captain,” Harold said. “He didn’t like men not following orders. That’s a hard habit for a commander. Tell him I said thank you.”

The son laughed wetly, and the room seemed to tilt and align. “He wanted you to know,” he said. “And he wanted you to know he knew.”

There was nothing in that moment to fix the horrible things war had done—no ledger that balanced the dead—but there was a kind of human arithmetic that mattered: acknowledgement, a hand on an old shoulder, the passing of gratitude from one generation to the next.

Harold died in 1998 at seventy-six. His obituary in the Grundy County Register mentioned his service in one passing sentence and then went on to say he loved his family, the farm, and the smell of cut hay. That was, to him and to those who mattered, the truth. The story of silent bunkers and white fires was told in histories and footnotes and veterans’ recollections, but the essence of Harold’s life was quieter: he’d loved the people around him enough to risk breaking a rule to save them.

There are, in the telling, complications that cannot be airbrushed. White phosphorus is not a benign thing. It burns and smokes and kills indiscriminately; it leaves marks that last. Some of those marks were left on Japanese defenders who had dug themselves into caves and had then been smoked out. War, always, is tangled with this moral hard knot. When Harold threw the first M15, he did not dream in technicalities; he saw men with names and faces, men who might go home to brides and children if someone could find a way to get them out of coral teeth. He gambled on human life, and he won in that small instant.

After the conflict, arguments persisted in quiet rooms and in policy papers about whether methods that circumvented manuals were permissible, whether the ends justified the means, whether human lives were a variable to be optimized at the expense of other moral claims. The army did what organizations do: it adapted in small, bureaucratic ways. Manuals were amended not by fanfare but by footnote. In classrooms at infantry schools, instructors told the story of the BAK campaign as a case study—“innovation under fire”—and emphasized judgment, the importance of measuring risk, and the responsibility to protect one’s men.

Harold never liked being called an innovator. It sounded too grand. He was a farmer who understood throws and a soldier who had watched his friends die for methods that were plainly failing. Perhaps that is what heroism looks like—an ugly, quotidian thing that involves deciding in a messy world not to defer to paper when flesh and life are at stake.

On warm summer nights at the farm, after the cows were milked and the babies were fed and the light in the kitchen had gone soft, Mary would sometimes sit by Harold and watch him peel potatoes. “You were a brave man,” she’d say. Not because a paper said so, but because she had seen him come home with mud in his hair and a silence in his jaw. “We were worried,” she’d add, because it was the truth.

Harold would only shrug. “I did what I had to do,” he’d say. “A man sees a way to keep his friends alive, he takes it. Ain’t no glory in it.”

But there was glory of a kind: in letters received decades later from men who had been under his command and who wrote in cramped, shaky handwriting about dances they had gone to and weddings they had attended and children who would not have been born if not for a farm kid who had tossed two heavy grenades into the hungry mouth of a coral bunker.

There is a lesson in that quiet, too—a kind of moral arithmetic that modern doctrine tries to teach in classrooms: regulations are tools, not masters. Rules exist to protect and structure action, but they were made by people who could not anticipate every battlefield. In the end, the responsibility remains with the person in the moment: to think, to choose, and to live with the consequences.

On Biak, men died who never got to see these arguments played out. Their letters arrived late, if at all. Their names are carved on memorials and whispered by grandsons and daughters on certain days of the year. Harold always carried that in him. He took nothing for granted. When the old man from Winters’ family clasped his hand in that hall in Des Moines and spoke with tears, Harold felt the weight of all those names in a way that made him half-laugh and half-weep.

“What would you have done differently?” the man asked him once, later, in the quiet of a reunion room.

Harold thought of the mornings when he had been a boy throwing bales, of the way corn slanted in rows, of his father’s face as they argued the fine point of planting. He thought of Tommy and of the medic and of men who had stretched and breathed and then been gone. He thought of the letters from men who had been children at the time and who wrote now with children and grandchildren and a voice full of gratitude.

“Not much,” he said slowly. “Maybe been a mite more careful sometimes. Maybe not have got so close. But if I’d followed the manual to the letter? They’d be numbers on a report somewhere. Ain’t life worth more than that?”

The man nodded and took the hand Harold offered. It was a small reconciliation—two men acknowledging a truth they could both hold. That kind of thing keeps the world balanced in its necessary, fragile way.

In the end, Harold’s legacy was not in plaques or parades. It was in the quiet arithmetic of lives returned to tables and churches and fields. It was in a son who grew up to farm a patch of land and teach his own kids how to throw a baseball so it would land exactly where he wanted it to. It was in a testimony that taught students at infantry schools to think hard and use judgment, not to worship doctrine when it contradicted reality.

Sometimes heroes are forged in the peculiar temper of necessity. Sometimes they are simply people who look at the mess and choose a path—reckless, perhaps, to some; brave and human, to others. Harold Moon, who had dropped out of school after the tenth grade to learn the honest labor of a farm, never wanted to be remembered as a savior. He wanted, as he had once told Captain Winters, only that his friends come home alive.

That is how he lived, and that is how he wished to be remembered: not for the fire he threw into coral, but for the hands he held at the end of a long day and the quiet, stubborn hope that a man could do right in a world that often insisted on something else. In the end, the numbers, the reports, the footnotes in manuals—all of them mattered less than the way men warmed to their families’ light across decades because one farm boy trusted his instincts more than an ancient sheet of rules.

Sometimes the world needs a person willing to break the rulebook in order to keep its people alive. Harold Moon did that. He took his medal to a drawer, came home, repaired fences, and watched his daughters dance at their weddings. Around him, the world remembered and argued, but inside his kitchen the simple truths endured: care for your neighbors, weigh your choices, and never confuse procedure with conscience.

Maybe that is, in the end, what heroism really is.

News

Sir, I Heard a Groan in the Tomb” — What Came Out of the Earth Made the Millionaire turn pale

Miles got sick fast. So fast it didn’t feel real. One minute he was sprawled on the living room rug,…

Come With Me… The Millionaire Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kid abandoned in the Road

The dirt road looked like it had been forgotten on purpose. Not abandoned in a romantic way, not the kind…

Millionaire Visited His Ex Wife And Son For The First Time In 8 Years, Changed Their Life Overnight

Michael Harrington had always been good at leaving. He could walk out of a meeting worth millions without glancing back,…

Millionaire Gets In The Car And Hears A Little Girl Telling Him To Shut Up, The Reason Was…

The drizzle had just begun to turn the cobblestone slick when James Whitmore stepped out of the historic hotel, the…

Most Beautiful Love Story: She Signed Divorce Papers, Left Pregnancy Test At Christmas Eve

Snow drifted past the windows of the Asheville Law Office like soft ash, quiet and slow, almost gentle inside. Nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load