Mira’s fingers trembled as she turned the pages. There were notations in the margins: dates, small crosses, sometimes calculations. The handwriting changed over the generations, but the message remained the same — a devotion to a single principle annotated again and again: keep the blood pure. Nell read the phrase and felt its weight as a physical pressure.

“How long?” Mira asked. Her voice had gone small.

“Since 1649,” Nell said. “Sixteen generations.”

Mira closed the Bible with the reverence of someone who understood that books sometimes saved you from repeating themselves. “It’s a kind of cumulative ruin,” she said. “When a gene pool is isolated and the same alleles are passed over and over, recessive mutations that once lay dormant become the rule. There’s a name for it — inbreeding depression. But it’s more than biology. It’s a moral collapse when the family’s identity becomes more important than its children.”

Nell thought of Ada’s stories: a child with an extra finger hidden away, a crying woman whose baby had not lived, a little boy who never spoke and sang to no one. “Ada always said there was a boy,” she said. “She’d hush when she told me his story. She said he didn’t belong to the world and the world didn’t belong to him.”

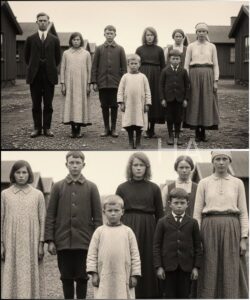

When Mira took the photograph and held it up, something in Nell’s chest loosened. The boy in the picture was twelve, according to the penciled note on the back. The caption read: William Mather. Born 1938. Died 1993. Last of the line.

“How did we never know?” Nell asked. “If it was this bad, how did no one intervene?”

Mira’s answer was not simple. “Privilege isolates. Wealth funds secrecy. A family that owns land and doctors and private tutors can create an alternate reality where outside scrutiny becomes a threat. They guarded the family line because the line was their identity. People in power often mistake preservation for virtue. Look at the ledger — they recorded everything and yet admitted nothing.”

They read together in the brittle light for hours, tracing the entries that told a story in more than dates: stillbirths, infants who lived a few days, children who suffered seizures, limbs that failed to form properly. Between entries, in a different hand, a physician had begun to keep a journal. Harold Brennan was his name. He had been the Mathers’ doctor for thirty years.

The journal was a different kind of text. Where the Bible contained ritual, Brennan’s writing contained doubt. He wrote of unease. He wrote of a child delivered in 1938 who should not have been able to survive given the cumulative genetic load. He described the boy — William — in clinical terms and then stopped at the thing that made him shudder: the child’s eyes. “He seemed to be looked through,” Brennan had written. “There was an otherness there I cannot explain.”

Nell read the sentence twice. The air in the reading room felt thin.

“We should publish this,” she said before she could stop herself.

Mira looked at her with the kind of caution that comes from knowing how stories explode. “We can’t just publish. There are people still alive who remember. The name Mather — you can’t just drag the bones of a family into the light without acknowledging how much pain you risk creating. You’ll need descendants’ consent, you’ll need the university’s counsel, you’ll need …”

“Justice,” Nell said. “Maybe.”

There was a silence like a held breath. Outside, a delivery truck thumped past the stone columns of the archive. In those three beats, Nell thought of Ada at the kitchen table, needle suspended, eyes on the fire. She thought of the child who had stood looking at the camera like a warning. She thought of all the small compromises that become a culture.

“We should at least try to find who’s left,” Mira said finally. “We should find the servants’ descendants first. They deserve to be told by us, not by journalists who only want a headline.”

Ada’s son — Nell’s father — had always been a man of silence. He would lift his coffee mug, nod at the photograph on the mantel of Ashford Hall — a ruin of a portrait given in better light — and change the subject. “Some houses close their doors for a reason,” he would say.

Ada was gone by then. She had died when Nell was three, leaving fragmented recollections stitched into lullabies and recipes: ash cakes, beans cooked with sage, a particular lullaby that began with a line about the moon being a white button in the sky. Nell had all Ada’s things in a trunk. Among them was a brittle tape recording Ada had made one winter at the insistence of a local historian. “For when I’m gone,” Ada had told the interviewer. “I don’t want them to think only the house remembered.”

Nell played the tape for Mira in the archive after they had read the Bible and Brennan’s journal. Ada’s voice came across nasally and slow, like someone savoring every syllable.

“They had a child with the wrong organs,” Ada said plainly. “We called him the mirror boy. He would stand and watch the wallpaper in the library for hours. Sometimes he’d say things that made my cat hiss. Mrs. Mather — she cried a lot in her room. She was a kind woman, but the house ate her. I was small, but I remember the funerals. They buried the children in a place that we were not to speak of. The Mathers did not like anyone to speak of what happened here.”

Mira’s hand lay on the tape recorder as if she could touch the past. “This is valuable,” she whispered. “Oral histories are the bones of a truth that official records won’t tell.”

Nell thought of how easily the family had closed itself off, how simple it was to hang a curtain and pretend the world outside was a storm to be warded away. She thought about the line in Brennan’s journal: “I have delivered a child who should not exist.” The sentence felt like a verdict.

They began to look for people. The university’s =”bases were not as comprehensive as the internet had made us think; small towns kept their own stories under the floorboards. But people talk at church potlucks and laundromats and in the long lines at the post office. Nell and Mira drove to the town nearest the old Ashford property and began to ask.

“Mathers?” an elderly woman at the diner said. “Lord, don’t start no trouble. They were a strange breed.” But she knew where Ada had worked. She could tell Nell the name of the priest who had officiated the private chapel, though the priest had died years earlier. A retired groundskeeper said he had planted bulbs in the estate garden three decades ago and had never been paid for the last season.

Piece by piece, a mosaic of recollections formed: a boy who never laughed, a woman who hid her face in a veil, a family that kept to itself like an animal wounded and ashamed. They found a few people who had last names in the Bible and who still lived within reach, scattered relatives who had left the line for marriage and survival. Most were reluctant to speak. None complained that the Mathers’ secrecy had been surprising.

But the most important voice was Ada’s descendants, who owned a small house in the subdivision that had been built over the old Ashford grounds. Ada’s granddaughter, Tessa, was a schoolteacher with a laugh that made her face crinkle like a well-thumbed book. She remembered stories — not all of them pretty — and she remembered the headstones that had been moved “when they decided to build houses.” Her children played in a yard where marble markers had once read names that were no more.

“You want us to remember?” Tessa asked when Nell came with the Bible and the photograph and the recording. She sat at the kitchen table with a paper cup of coffee and watched Nell like someone waiting for the storm to tell them what to carry to shelter.

“We want to tell this story properly,” Nell said. “Not to shame, but to explain. To remember the children who were lost. To understand why our communities must never let a family’s pride become a law.”

Tessa’s jaw worked. “My grandmother would want the truth told. She would want them named,” she said. “We used to say their names under our breath, like prayers. I want a place in the park where my kids play now — a plaque. A bench. So people know what was done in the name of pedigree.”

Nell felt the first seams of what she’d been looking for: not a scandal, but a renunciation. The people who had served the Mathers — not just Ada — deserved truth, not silence.

“Will you help me?” Nell asked.

Tessa gripped the cup as if it were a life ring. “Yes,” she said. “But we do this together.”

The hardest part was the coming face-to-face with the Mathers’ last living relatives. There were a few, not by blood but by marriage and proximity: a cousin who had taken a new name to marry a man in Richmond, a niece who lived quietly in a retirement community and signed her mail with initials that masked the surname. The legal family had left the estate long before, scattered like seeds. But there was one person who still carried the old name with a clenched jaw: Miriam Mather.

Miriam was ninety-two and lived in a small brick house with trimmed hedges that looked like a portrait in slow motion. She had been a child of the later generation — raised within the boundaries of the covenant but with enough external contact to leave her options narrowed rather than sealed. Her son had fled as soon as he could; her husband was gone. Miriam kept the portrait of Ashford Hall on her wall and covered it at night with a crocheted shawl.

“She won’t speak to strangers,” the woman at the front desk of the assisted living facility warned them. “Mrs. Mather’s mind is sharp but her pride is sharper.”

Nell and Mira both felt the weight of that word before they rang the bell. Miriam answered herself, as if she had expected them. Her eyes were the same as the boy in the photograph — a deep set that regarded you by measuring your intentions as if they were a ledger.

“Do you want something?” she asked.

Nell stepped forward, the Bible pressed to her chest like an accusation. “My name is Eleanor Rivers,” she said. “My grandmother Ada worked at Ashford Hall. We have papers. Photographs. A journal from Dr. Brennan.”

Miriam’s face remained carved with a stillness that was almost ritual. “We’ve been studied enough,” she said. “If you want to make trouble, take it elsewhere.”

“We don’t want trouble,” Mira said. “We want to understand, and to give the children a voice. Your family… the Mathers taught for generations that they were preserving something. But preservation can be destructive when it becomes an idol.”

Miriam’s jaw tightened. “You speak as if you have the authority to judge my family.”

“We only have the authority of fact,” Nell said. “And memories. Dr. Brennan’s journal said what he saw. Ada’s recording talks about a boy named William. We want to put a marker where the children were buried. We want a public acknowledgment that mistakes were made.”

Miriam’s eyes flicked to the Bible Nell held. “I don’t authorize strangers to come and take my family’s sins and make them a spectacle,” she said. “William was my cousin. He was —” Her voice fractured. For the first time there was both a crack and a human sound there, like thin glass breaking.

“He was a child,” Nell said softly. “William didn’t create the world he was born into. We are asking you to help us tell the truth so future parents know what pride costs.”

Miriam’s silence stretched. The room seemed full of the slow tick of decisions. Then she did something that surprised both Nell and Mira: she invited them in.

Inside Miriam’s house the world had been condensed. Portraits lined the walls like constellations of memory. There were objects wrapped in linen, names on placards. Miriam poured tea into delicate cups and sat, not like a woman expecting to defend herself but like someone preparing to remember.

“You are young,” she said, and the words were neither reproach nor praise. “My father told me I must keep the line. It was the way of things. You do not know what it is to be raised on the idea that to lose your name is to lose yourself. It becomes part of your bones.”

“I know that,” Nell said. “Ada told me how they’d hush things, how they’d bury children in the family yard.”

Miriam’s breath left her in a slow exhale. “We hid the infirmities because we thought shame made them less likely to appear. Stupid. Superstition. But we believed we were protecting a heritage.”

“Did you ever worry?” Mira asked. “Did anyone in the family ever say this is madness?”

Miriam’s hand trembled as she brought the cup to her lips. “There were whispers. When Catherine wanted to leave — she wanted to marry outside the line — my grandfather said he would strike her from the Bible. She stayed. She had children. She mourned. I watched my cousins die in silence. We told ourselves that God took the weak. But one does not decide what God takes. We decide what we honor in his name.”

Then Miriam surprised them again. She reached into a drawer and produced an envelope that had yellowed with decades. Inside, folded like a fragile bird, was a letter. Miriam placed it between her trembling fingers and gave it to Nell.

“This was my brother Thomas’s,” she said. “He tried to leave and then came back. He wrote to say he was sorry. He asked us to stop. We did not. We claimed the law of family was higher than a man’s plea.”

Nell read the letter with a sensation like walking across a glass floor. The handwriting was hurried, angry and pleading in the same breath. “What have we done?” the letter read. “We have made our children currency, and in the trading we have spent their lives.”

Miriam’s eyes filled and the shield she’d worn for decades slipped. “He killed himself three years later,” she said. “We pretended it was illness. It was shame. We pretended we were strong. We were a house of bones.”

The confession did not heal anything with a single exhale — that is not how history yields itself — but it moved something that had been fixed into place. It made the past porous.

“Will you help us put a marker?” Nell asked. “A plaque. A small memorial where the cemetery once stood. Not to sensationalize the Mathers but to name the children and to say that this was wrong.”

Miriam held the letter against her chest. “If you want to make a spectacle, go ahead,” she said. “If you want to remember the children, then yes. I will help.”

Her consent was not absolution. It was an offering.

The hardest part, Nell had learned, was assembling people who had reason to resist being reminded of old sins. The developers who had built the subdivision were wary of memorials that might dent the charm of their advertisements. Local politicians wondered about property values. But the people who had lived on the land for generations, and the descendants of the servants who kept the house, were the ones who made the difference. They met in a school gymnasium on a Thursday night lit by fluorescent lights and brought casseroles and patience.

Nell stood at a podium that had been borrowed from the PTA. Tessa sat in the front row with her children, who had crayons on their shirts. Mira had prepared a short talk about how scientific humility could coexist with public memory. Miriam sat in the back with the letter on her lap.

“I’m not here to shame anyone,” Nell said into the microphone. “I’m here because if you build a culture where secrecy and pedigree trump life, you will eventually pay for it. That’s not a moralizing slogan. It’s a simple lesson from a family that loved its own image more than its children. William Mather was a person. He did not deserve to be hidden. The families who were servants did not deserve silence.”

There were people in the gym who had family members in the photograph who had been erased from the public record. There were also families who had recently bought houses in the subdivision and worried about the stigma they’d be associated with. Someone in the crowd — a middle-aged man with eyes like a bank clerk’s — stood up and demanded why the Mathers were being singled out when every family had secrets.

“Because the Mathers’ secret had consequences,” Mira said. “Because their choices culminated in a lineage that left a child so genetically damaged he could not thrive without intense medical intervention. Because we need to learn from this and change our culture so that love is not measured in how pure your blood is.”

There was a long, messy conversation. People banged on tables with their hands. Someone cried. Someone else made a joke to defuse the tension. In the end, the town agreed to a modest proposal: the developer would donate a small parcel of land for a memorial garden; the county would place a small plaque that told the story of the children who had died and named William; the university archives would make the Mather Bible available to researchers; and a fund would be established to support genetic counseling and outreach in rural communities, where misinformation often thrived.

It was not grand. It was not enough. It was, in its own way, honest.

On the morning the ground was broken for the memorial — a small circular garden with benches and a stone plinth — Miriam arrived in a blue cardigan and walked as slowly as if each step was an apology. She stood at the edge of the ceremony and watched the gardener plant bulbs that would bloom long after any of them were gone. Ada’s great-grandchildren were there, their hands dirty, planting a sapling that would grow where marble once lay.

Nell read from Dr. Brennan’s journal and from Ada’s tape recording. She read the passages aloud not to vilify but to witness. “There are some things medicine cannot explain,” Brennan had written. “There are some outcomes that science predicted, but humanity refused to believe.” Nell’s voice shook as she spoke the words; she had known them for months now, but saying them aloud made them more than sentences on brittle paper. They became an obligation.

Afterwards, when the crowd had thinned and the sky had turned the metallic blue of a late afternoon, Miriam asked to speak with Nell alone. They walked between the budding roses and the saplings, and Miriam’s spindly fingers found a bench and sat like someone who had spent a lifetime carrying too much weight.

“You were brave,” Miriam said. “You came with a family’s sins and gave us a chance to be human about it.”

Nell’s throat tightened. “You gave consent.”

Miriam’s hand brushed the letter in her lap. “It was time,” she said. “I thought we were preserving something noble. I thought to keep the line was to keep meaning. I was wrong. I watched my cousins die and told myself God had reasons. That’s cowardice disguised as faith. If anything I have left is worth anything, it’s that I can say I am sorry.”

“How do you forgive yourself?” Nell asked.

Miriam laughed softly, a sound like a clock struck on a bell. “You don’t,” she said. “You only stop making the same mistake. Forgiveness is overvalued, child. What matters is repair. Planting trees. Naming names. Telling children that their blood is not their worth. That is how you begin to make amends.”

She reached out and took Nell’s hand, surprising her with the warmth of it. “Promise me you’ll tell them,” Miriam said. “Write it down. Let the children learn their history. Let them know that sometimes the worst sins of our ancestors can be corrected by the smallest acts of courage.”

Nell promised.

Years later, when the sapling had grown into a tree and the plaques had smoothed with weather, children came to the garden to play. Sometimes they read the plaque and asked their parents what a covenant meant. Sometimes adults sat on the benches with their heads bowed and their pockets heavy with the small, private confessions that come later in life when people start to account. Ada’s descendants taught a class at the local school about oral history. Mira published a paper that used the Mather family as a case study in ethical genetics — not a scientific exposé but an account that emphasized human cost. The university added a small exhibit in the local history museum about communities that closed themselves to the world and the consequences.

The memorial did not change everything. People still held prejudices. Old habits are like hedges, needing repeated pruning. But the story of the Mathers — of sixty children who had been recorded and then recorded no further, of the boy with right-sided heart and mirror organs — became a cautionary tale in local curricula. Doctors in the county report more willingness to counsel families and to offer genetic services. The fund established in the wake of the memorial paid for free counseling and, once, for a child from a nearby farm family to see a specialist in Richmond.

One spring, Nell watched a group of first-graders run through the garden and then sit under the tree to hear a story. A small boy with braids and a gap tooth asked, “Why did they keep marrying the same people?” The teacher, a woman who had once been Tessa’s student, smiled and said, “Because sometimes people value an idea more than a person. But we can choose better.”

Nell felt the truth of Miriam’s words in the warm air: repair matters more than absolution. She thought of the photograph in the archive, of the ledger in the vault, of the letter trembling with its old shame. She thought of Ada’s voice, which had been recorded and preserved and then at last publicly played in a room where people could listen without fear.

At the end of her life, Miriam died quietly, with the letter folded on her nightstand. They buried her in the municipal cemetery alongside the moved headstones. The funeral was small and honest. Miriam’s son — who had not come for years — stood and read a line from his mother’s letter that had always made him ache: “We made our children currency, and in the trading we spent their lives.” He whispered, “We will not spend more.”

In the years that followed, the Mathers’ Bible remained in the archive, but the university had digitized it in full with redactions only where privacy laws demanded. Families, scholars, and students could see both the entries and the omissions. The photograph of William was not used as spectacle. It was part of an exhibit with a simple caption: William Mather, 1938–1993. Last recorded descendant. A life worth more than the story it ended.

Nell kept a copy of the photograph in her desk. Sometimes, late at night, she would take it out and place it under her lamp. The boy’s eyes did not look through her so much as they asked, in that old, patient way children sometimes have, to be seen as human.

She married once, to a man who had been a childhood friend and who loved her because she could sit quietly in a storm and make a meal. Together they planned their life not as a lineage to be preserved but as a conversation to be continued. When they had a child, the birth announcement did not note pedigree. It noted a name, a home, and a gift of curiosity. Nell thought of the covenant and of the way the Mathers had believed purity could be engineered like a garden hedge. She thought of the simple fact that life, like soil, is richer with variety.

One morning, years later, she took her child to the memorial garden. The boy — small, already curious — reached up and touched the bark of the tree that had been planted in memory of children who had been buried and moved and finally named. Nell watched her son run with other children and thought of the strange, wide world that had once been kept out by shutters that stayed shut too long.

“What did you learn in school today?” she asked her son as they walked home.

He looked at her with earnestness and said, “We learned about a family that loved their name too much.”

“And?” she prodded.

“And we learned that names don’t have to hurt us,” he said.

Nell felt something like relief and then something like grief, both mingled. She thought of Miriam’s letter, of Ada’s recorded lullaby, of Dr. Brennan’s trembling admission. We are capable of great shame, she thought. We are also capable of small, persistent courage: telling the truth, naming the dead, planting a tree where a headstone once lay.

At the archive, the photograph stayed in its box, beneath glass and climate control. People requested it from time to time: historians, students, curious neighbors. They asked for the ledger. They read the names. Sometimes they asked about the boy’s eyes.

A small plaque had been set into the garden’s low stone wall. It read, simply:

Here, families once buried their children in silence. We remember them now. We remember Ada and the housekeepers who kept the records and the secrets. We remember William, and the consequences of believing purity was worth more than life. Let this place be a lesson and an offering: choose repair over pride.

It was neither a sermon nor an epitaph. It was a promise stitched into stone.

There is a photograph locked in a vault in Virginia. But it is no longer only a warning. It is part of a ledger that names both the sin and the remedy. It tells of a family that believed in purity as an end, and of a town that learned to make amends.

When Nell closed the ledger one evening, she felt the world was not cured. It never would be. But she also felt — as a summer breeze stirred the garden and children laughed in the nearby subdivision — that repair is possible if one chooses it. That is a small mercy. For some families, it comes late. It comes with gray hair and with letters unfolded and with people who ask to be forgiven and who then do the work of not repeating.

On the photograph in the archive, the boy still stares out. The archive label now reads: William Mather, 1938–1993. Last page closed. The last page, perhaps, but not the last lesson.

News

Sir, I Heard a Groan in the Tomb” — What Came Out of the Earth Made the Millionaire turn pale

Miles got sick fast. So fast it didn’t feel real. One minute he was sprawled on the living room rug,…

Come With Me… The Millionaire Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kid abandoned in the Road

The dirt road looked like it had been forgotten on purpose. Not abandoned in a romantic way, not the kind…

Millionaire Visited His Ex Wife And Son For The First Time In 8 Years, Changed Their Life Overnight

Michael Harrington had always been good at leaving. He could walk out of a meeting worth millions without glancing back,…

Millionaire Gets In The Car And Hears A Little Girl Telling Him To Shut Up, The Reason Was…

The drizzle had just begun to turn the cobblestone slick when James Whitmore stepped out of the historic hotel, the…

Most Beautiful Love Story: She Signed Divorce Papers, Left Pregnancy Test At Christmas Eve

Snow drifted past the windows of the Asheville Law Office like soft ash, quiet and slow, almost gentle inside. Nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load