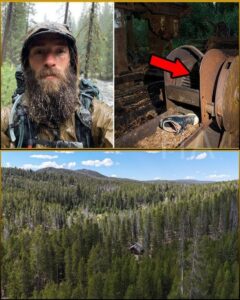

When 32-year-old programmer Greg Morrison vanished in Georgia’s Chattahoochee National Forest in September 2001, few imagined the truth would surface four years later — inside a Cold War bunker buried beneath the earth, where his phone flickered to life one last time.

The Signal

It began with a blip.

In March 2005, a technician at a cellular company monitoring dormant numbers noticed a brief, impossible signal — a phone inactive for four years suddenly connecting for five seconds in a remote forest region. The number belonged to Greg Morrison, missing since 2001.

“It shouldn’t have happened,” technician Harold Dean later recalled. “The account was closed, the phone dead. But the system showed coordinates — deep in the woods, miles from any tower. That’s what scared me.”

Dean reported it. Within days, rangers and police hiked into the rugged northern Georgia wilderness. What they found was a discovery that stunned the nation and forever changed the meaning of “missing.”

The Disappearance

Greg Morrison had been the picture of an ordinary man trying to heal. A quiet software developer from Atlanta, recently divorced, no children, no scandals — just a solitary hiker who loved nature.

“Greg said the forest helped him think,” his former boss, Alan Pierce, said later. “He was the kind of guy who’d bring trail maps to lunch meetings.”

On September 14, 2001, Greg left for what he called “a solo reset.” He packed a tent, supplies, and his old Nokia cellphone. He signed in at the ranger station, cheerful and confident. A ranger on duty, 64-year-old Bill Hopkins, remembered him vividly.

“I told him the weather might turn rough,” Hopkins recalled. “He just smiled and said, ‘That’s part of the fun.’ He knew what he was doing.”

When Greg didn’t return on September 18 as planned, coworkers assumed he’d extended the trip. By the third day, his boss called police. His car was found untouched in the trailhead parking lot — locked, no signs of struggle.

Then came the long silence.

For two weeks, volunteers, helicopters, and dogs combed the area. The scent trail vanished near a stream. “It was like he’d evaporated,” Hopkins said. “No tent, no trace. Just gone.”

The case grew cold. His parents, from Ohio, visited every few months, posting flyers. His father searched the trails until his knees gave out. “We thought maybe he fell, maybe got lost,” his mother later told reporters. “We never imagined…”

The Bunker

The 2005 signal led officers twelve miles from the nearest road into terrain so thick they had to hack through undergrowth with machetes. As dusk fell, one ranger noticed something unnatural — a low mound too symmetrical to be natural.

Under moss and roots, they unearthed a concrete wall and a rusted steel door disguised as rock. When they finally cut it open, the stench hit like a wave: decay, mold, and something older, heavier.

Flashlights revealed a descending corridor lined with mildew-coated concrete. At the bottom, they entered a large chamber.

And froze.

Four skeletons sat chained to a pipe along the wall, their ankles bound with rusted iron.

Each had been a person once — still clothed in shreds of jeans and shirts, shoes on their feet, surrounded by empty cans and bottles.

Near the last body lay an ancient Nokia cellphone and a piece of frayed electrical wire. Investigators quickly realized what had happened: a fallen live wire from the bunker’s old circuitry had brushed the phone’s contacts, briefly charging it — long enough to send that five-second signal to the cell network.

That random spark had led rescuers to a nightmare buried for nearly two decades.

The Victims

DNA tests identified the remains as:

Robert Hansen, 53 — a history teacher who vanished in 1988.

Jennifer Cole, 27 — a nurse lost in 1999.

David Price, 43 — a fellow programmer missing since 2001.

Greg Morrison, 32 — the last to disappear.

Each had vanished years apart while hiking alone in roughly the same region. Their names, etched with fingernails or stones, were scratched into the concrete wall beside hundreds of tally marks — four years’ worth of days counted by someone desperate to stay sane.

“We counted 1,340 marks,” said Detective Ray Carter. “That means at least one of them lived down there nearly four years. Imagine marking every sunrise you’ll never see.”

The Diary

In a side room, investigators found a notebook lying on a rusted metal table. Inside were 16 years of handwritten entries.

“Brought the first one today,” the earliest note read. “Male, about fifty. Subject will serve as baseline for experiment.”

The author: Howard Lamb, a retired Army officer who’d lived alone in a cabin eight miles away.

Lamb’s diary chronicled what he chillingly called his “experiment.” He had discovered the abandoned Cold War bunker in the 1990s and decided to use it for “psychological research” — observing “human endurance under prolonged isolation.”

He abducted hikers one by one over 16 years, knocking them unconscious with chloroform, chaining them in the bunker, and visiting weekly with food and water.

He didn’t torture them physically. He simply waited — watched — recorded.

His entries were cold, clinical:

Day 30: Subject has stopped begging. Eats less. Water usage normal.

Day 400: Subject 1 weakening. Subject 2 attempts to comfort him.

Day 600: Subject 1 deceased. Remaining subjects distressed. Continue observation.

The final entry, June 2004, read:

My health declines. Liver cirrhosis. Experiment ending. Will not return.

He stopped visiting. The captives, left without food or help, marked days until they died.

The Monster Next Door

Howard Lamb died two months later — August 2004 — of liver failure at 62. His body was cremated quietly. No one suspected he had spent decades abducting hikers.

When police entered his home, they found dozens of other journals and maps of the forest marked with seven points — likely previous abduction sites. In his basement were backpacks, sleeping bags, and personal belongings from unidentified victims.

Neighbors described him as “polite but odd.”

“He kept to himself,” one woman said. “Always out walking in the woods with a pack. We thought he was just another vet who liked hiking.”

He was more than that. He was a methodical predator — disciplined, emotionless, obsessed with control.

Psychologists later reviewing his writings concluded Lamb wasn’t insane in the legal sense. “He saw it as research,” said Dr. Alan Weber, a forensic psychiatrist. “He believed he was studying ‘mental endurance’ — not committing murder. That’s what made him so terrifying.”

Aftermath

The families received the news in waves of devastation.

Greg Morrison’s parents sat silent as detectives explained. “Four years,” his mother whispered. “He was alive for four years.”

Jennifer Cole’s father refused to believe it until shown her wristwatch, still on her skeletal arm. “She never took it off,” he said, crying.

Robert Hansen’s grown daughter, estranged for years, learned her father hadn’t abandoned her as she once believed. “He didn’t leave us,” she said. “He was stolen.”

The state demolished the bunker in 2006. Officials feared it would attract morbid curiosity. “Some places don’t deserve to be remembered,” one ranger said.

Lamb’s cabin burned down mysteriously months later. Locals called it justice. Police never investigated.

The Forest Remains

Today, the Chattahoochee trails are still open, though hikers now register routes and carry GPS trackers. Rangers say they still get questions about “the bunker.”

For most, the story has become legend — a dark whisper in the pines. But for the families, it remains an unending echo.

Four people walked into the forest seeking peace. They found a man who mistook cruelty for science.

And in the end, it took a dying phone and a single flicker of electricity to bring their voices — silent for years — back to the surface.

News

Boy Scouts Vanish in 1997 — A Buried Container Unveils a Decade-Long Horror

Boy Scouts Vanish in 1997 — A Buried Container Unveils a Decade-Long Horror It was a July afternoon in 1997…

Police Sergeant Vanished in 1984 — 15 Years Later, What They Found Was Too Horrific to Explain

Police Sergeant Vanished in 1984 — 15 Years Later, the Truth Emerged Too Horrific to Comprehend Sergeant Emily Reigns had…

FAMILY VANISHED in Death Valley… 13 Years Later, 2 Hikers Make a Shocking Discovery

Family Vanished in Death Valley: 13 Years Later, Two Hikers Solve the Mystery In the summer of 1996, a seemingly…

Hiker Disappears On Trail. Years Later, He Returns With A Shocking Story!

Hiker Disappears on Trail, Returns Years Later With a Shocking Story It was a foggy morning in late August when…

Father and Daughter Vanished on Mount Hooker — 11 Years Later, a Discovery Changed Everything

Father and Daughter Vanished on Mount Hooker — 11 Years Later, a Discovery Changed Everything Sometimes, the mountain doesn’t take…

They Sent the Obese Girl to Clean His Barn — But the Rancher Refused to Let Her Go

The boarding house kitchen smelled of burnt coffee and stale bread. Sunlight slanted through grimy windows, dust motes dancing in…

End of content

No more pages to load