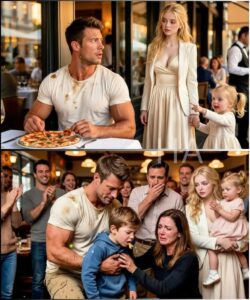

His shoulders eased as the first slice warmed his hands and the kitchen’s garlic reached his nose. He had given himself permission to be ordinary that night. Then, like a bell tugging him back to attention, a small voice said, “Mommy, I like him. Can we sit with him?”

A woman stood with a child at her hand. The little girl—Mila—had a soft tumble of brown curls and a curiosity that arrived like sunlight. The woman beside her wore her hair loose and simple, and her dress was cream, the kind of elegance that didn’t need announcements. But what struck Eli more than clothes was the look in the woman’s eyes: a tired kind of strength, as if she were both shield and weather. She apologized for her daughter before the request was made and offered to sit. Eli, who had never been good at saying no to the small mercies of company, nodded.

They ate pizza and talked. It was the easiest kind of conversation—one that happens when strangers lower the parts of themselves that wore best in solitude. The child danced over to him with the natural authority of someone who belonged to no vanity, and called him “superhero” because he had shown Mila that it was possible to make faces with a crust and then stop when the baby in the booth started crying.

When a child at a neighboring table started choking—throat closing, face going red—Eli moved without thinking. There was a calm certainty in his hands as he performed the Heimlich, a casual muscle memory from volunteer training at the community center. The boy expelled his terror in a cough, the restaurant exhaled in relief, and when laughter and applause followed, Eli ducked like someone who never sought an audience. Savannah Langford watched him and felt something unfamiliar in her chest uncoil.

Savannah Langford was not like any woman Eli had met previously. She was the daughter of Harold Langford, the CEO of a company that made the town’s most admired cars and the man who often sat at the table that determined what was tasteful or necessary. Savannah’s life had been a string of windows—the big glass kind that showed only what the world wanted her to be: polished, poised, perfect. She’d married young and with the kind of urgency that betrayed a desire to escape rather than to build. That marriage had folded, public and sharp, and left her with a daughter and a reputation taped together with a thousand headlines. She had learned to armor herself in the currency of composure.

But something about Eli’s smallness was not contemptible. It was sacred. She watched him kneel to tie Mila’s shoe in the park, felt the way he spoke to parents with the simple reverence of someone who had not been taught to perform for crowds, and she found herself returning, like a moth to a candle that did not try to blind her. He fixed her car on the side of a busy street, hood open to the world, and his hands were both gentle and exacting. When Mila offered him a gold star from a sticker sheet, Eli accepted it like it was the truest sort of ceremony and stuck it on his shirt pocket as if that small sticker could become a kind of permission.

Rumors, like shadows, spread differently depending on the light. The office boys’ joke turned into whispers in bars and then into the neat, rumor-shaped headlines that circulate a small town with appetite and speed. They expected embarrassment, a red-faced retreat, but what they did not plan for was that Eli simply kept being himself. He let the mocking pass over him like rain over clay and continued to hold doors, fix a neighbor’s mower for free, and teach kids from the after-school program to hone a wrench without being rough.

Harold Langford noticed. He noticed because the world he ran depended on noticing—on perfect detail, on the knowledge that every narrative could be smoothed into the language of commerce. He drove down to the garage one day in a suit that had not been imagined for manual labor and asked Eli to step out from under the car. Harold said things he had been taught to say: protect, status, image. He told the mechanic to walk away. Eli, steady and polite, said Savannah chooses for herself.

“You don’t understand what you’re dealing with,” Harold told him in a tone that carried decades of men who had never known being told no. “You don’t get to climb above your station by courtship.”

“I don’t want anything,” Eli said. “I want to be there for Savannah and Mila. That’s it.”

“You think I don’t know what this looks like?” Harold’s face flattened into an adamantine schoolmaster’s brow. “You think I trust stories that start in garages?”

Eli did not flinch. He had learned to hold his breath and listen to the hum of an engine, and it steadied him now. “Sir,” he said, “I’m not trying to be anything but myself.”

Harold left, and for a while there was war in the air. Harold called conversations he thought were necessary. He spoke to reporters when he needed to steer perception. He tried to cast Eli as a curiosity, a man Savannah might pity. Savannah, however, had learned to fight like a woman for whom the interior life mattered more than the exterior trappings of approval. She told her father, in a voice that trembled only once, that she was not a thing to be managed.

They had fought, left the penthouse in opposing storms, then found themselves in a park days later where time moved like paint drying—slow, luminous, inevitable. Harold, a man who had been all engine and steel at the office, stood under an elm and watched. He watched as Eli repaired a broken stroller with the same easy competence he had used to coax a Fiat into life. He watched a child leap into the mechanic’s arms, watched his daughter smile in a way money could not buy, and something like a fissure opened inside him.

Harold had lived a life that equated value with scale: how many factories, how many boards, how much profit. This was not the first time it had served him well, but it had also been a life that produced a certain kind of blindness—an inability to see tenderness when it didn’t come wrapped in a hand-stitched logo. Watching Eli with Mila, he saw an unbought kindness that no ledger could contain. He did not decide to spoil everything and accept his daughter’s choice right away. He decided, instead, to observe and to consider whether greatness could present itself in a small, greasy package.

Time does odd things when people are honest. The office boys’s joke bloomed into a series of small, tender moments. Savannah and Eli saw each other in the ordinary places people live—groceries, the community center, the park. Eli took no steps to change who he was. He arrived with a patched jacket, a willingness to teach Mila how a carburetor worked if she cared to know, and a soft, unassuming patience. Savannah, who had long ago learned to tidy her feelings for public view, started to welcome imperfections like a secret remedy. She let Mila climb on his lap and watched the child be free in a way that softened her like water on stone.

But the world would not stop for tenderness. There had to be a climax that asked everyone to stand fully in what they believed. That moment arrived one humid evening when the community center’s “Stars of Service” fundraiser was in full swing. Langford Motors, trying to polish what could not always be polished, had sponsored a new initiative—Community Car Care—aimed at providing free basic maintenance for those who could not afford repairs. Harold was to give a speech; Savannah, quietly proud, had invited Eli to attend. Eli had not prepared lines—he never had. When the mic found him, however, the world hushed in a way it sometimes does when truth is about to be spoken.

A reporter asked him about the beginnings of his work, about the men who had once thought the blind date a laughing matter. Eli spoke like he always did—plain, steady, and without a hint of the bitterness that their prank might have earned him. He spoke of his mother and of the people who had taught him that a man’s worth was the sum of his kindnesses.

But it was when he looked at Savannah, who stood by with Mila grinning, that the room changed. He told a small story about a pizza and a child’s gold star and the way the smallest of people could see the best in others. Harold, in the crowd, watched his daughter’s hands curl around the child’s small shoulder and felt his hard conclusion begin to melt. The applause was more than for the program. It was a recognition of the kind of living that sews community into being.

After the speech, a woman approached Harold. She had been at the back of the room, a social worker whose clients had benefited from community car repair days. She told him quietly about nurses who could not get to shifts because of flat tires, about teachers missing parent-teacher nights when a car failed them, about janitors who could not afford the $200 the dealership would charge. Harold listened, and something in him—maybe fatigue, maybe new awareness—shifted into a strategy rather than a reflex.

He returned to the podium later and made an offer that surprised everyone including himself. He spoke of a new arm of Langford Motors: a dedicated program that would not only provide free maintenance but would hire people from communities who knew cars not as commodities, but as lifelines. “We need people who know how to talk to neighbors,” he said, “not simply to repair vehicles.” When he looked around the room, his eyes found Eli’s. “Eli Turner,” he said aloud, “we want you to lead it.”

Eli thought he had misheard. He tugged at his collar and laughed a little, the kind of laugh that hid the tremor in a man’s chest when the floor beneath him suddenly rearranged into something unfamiliar. Harold nodded, his expression raw and undecorated. “You showed me something I had lost the capacity to see. I asked you once to walk away. I ask you now to come with us. Help us build an initiative that sees people for who they are.”

There was no grand ceremonial ribbon. The deal was a quiet handshake, a brochure turned over on a crowded table. But the meaning of it was enormous. For Eli it was a chance to teach dignity in a place that would listen. For Harold it was a bridge he hadn’t expected to cross. For Savannah, it was the first time she heard her father offer something without conditions—an apology wrapped in an opportunity to do better.

The weeks that followed were busy with preparation and the clumsy grace of learning to work across lines that had formerly felt like boundaries. Eli walked through Langford Motors like a man walking through a museum he had helped restore. He chose the people who would staff the Community Car Care initiative with his same quiet instincts: women who had been single mothers and knew the cost of a dead battery; a retired mechanic whose hands were as steady as Eli’s but who needed dignity more than a check; young men who had never had a chance to learn a trade. Eli taught them how to check brakes with tenderness and how to explain to a scared parent that the car would be okay. The program grew by doing the work it promised, and the town, watching, began to notice that Langford Motors was changing into something less like an unapproachable factory and more like a neighbor that could be knocked on for help.

And the most important changes were not public. They lived in the small, private acts between Eli and Savannah. He learned how to be present for Mila’s recitals, how to tie a school uniform tie, how to sit through a child’s prolonged inquiry into dinosaurs. Savannah taught Eli about spreadsheets and investor meetings, not because he needed to attend them but because she wanted him to see the world she navigated and to understand the pressures he did not carry. They learned to be unflinching with each other about past losses and about the fear that lingered like a stain. Eli told Savannah about the time his uncle had shown him how to weld by the light of a single garage lamp. Savannah told Eli about the ache of headlines and the way public opinion had once felt heavier than gravity.

When they were apart, they missed each other like worn gloves miss hands. When they were together, they discovered that love sometimes arrives unannounced, and then asks the simplest things: show up, be kind, be honest. The town watched, and then the town settled into a new expectation: that people of means might do more than give money; they might give space for dignity.

On a late autumn evening, Mae Turner stood on the garage porch and watched as Savannah bent down to re-tie Mila’s bootlaces. The sky bled pink and gray, and the air was the kind that made conversation feel inevitable. Mae wrapped her cardigan close and smiled in a way that had room for both sorrow and joy. “I never thought I’d see my son with a daughter like hers,” she said quietly to herself. She had known, perhaps, that people find their places in ways that a map cannot predict.

The climax, of course, needed to be gentle. There was no melodramatic reckoning where Harold performed a sudden conversion. He moved slowly, as men of power often do when they truly change: through the steady accumulation of small acts. He sat with a young mechanic Eli had hired and listened to him tell the story of how he had learned to stay sober because someone had believed in his work. Harold funded scholarships for vocational schools and created policies within Langford Motors that made space for people who had formerly been ignored.

One night, Harold took Savannah aside on the balcony of his penthouse. The city stretched below, a net of lights. He put his hand over hers and did not sermonize. “You were right,” he said simply. “Not because I let you have what you wanted but because I finally saw what you saw. There is work in the smallness that matters.” Savannah, who had once packed her love into an unlabeled box and placed it behind a shuttered window, let herself unbolt her defenses that night. She forgave him, which was not a light thing to do, and in that forgiveness, both of them discovered a softer land.

Privately, the office boys—now men with wives and children and fewer jokes to spare—found their laughter less easy to use as a weapon. They frequented the garage less to mock and more to ask Eli about the Community Car Care days. One came by to apologize, bringing a plate of something his wife had baked, and the kitchen smell felt like truce.

Eli never forgot how the blind date had started as a prank. He told the story once, not with hurt but with a small grin, at a community event where they served pizza to volunteers. “You can start something ugly and end with a family,” he said, his voice quiet and unassuming. “Or you can start with a pizza and end with a whole town learning what dignity looks like.” The room laughed and then nodded; it was that kind of laughter that mended things.

In the end, the romance that grew between them was not the flashy kind. It was built in slow, truthful increments: in the way Savannah taught Mila to read at night while Eli didzeled away at a stubborn engine in the evenings; in the way Eli held Savannah when she had to face a cruel article; in the way they negotiated money and space, toys and time, public scrutiny and private tenderness. Mila, who had crowned Eli “superhero” on a night when he had rescued a choking boy, crowned him again in all the ways that matter, with stickers and invitations and the unreserved authority only a child gives.

Years later, as Langford Motors rolled out a nationwide model of community programs modeled on the pilot Eli had led, Harold watched a video of a small mechanic in a faded shirt speaking to a crowd of working people. The video showed hands callused and clean in the same frame, someone who had not moved to fit a mold but had instead carved out a space where everyone could belong. Harold felt something that resembled a miracle: a correction to a life that had once been all assembly and not enough heart.

Mae Turner grew older and gentler. She watched her son and Savannah sit at the kitchen table planning their next outreach and felt a tenderness that was both pain and gratitude. The porch light stayed on, but now it was the light people sought out in evening hours because it meant warmth and, often, a cup of kettle tea waiting.

They married in a small ceremony hosted at the community center with a ribbon of fairy lights, Mila between them, giggling every time she mispronounced the word “vows.” The office boys attended, their faces softer, their humor traded for applause. Harold stood at the back, a man who had learned that control could be loosened without losing the self, that gentleness was not a weakness but a tool. When he walked his daughter down the aisle he felt something like peace.

On the day the Community Car Care program marked its hundredth free service, Savannah put her hand in Eli’s on the stage. She looked at him as one might look at a harbor after a long haircut of storms: with relief, gratitude, and the quiet joy of being known. The crowd cheered, and Mila jumped up, placing a gold star on Eli’s apron. “For hope,” she declared to the cheering room. Eli laughed and then kissed Savannah, a quick press that had the weight of years and the extraordinary lightness of finally choosing.

The town learned, slowly, that status could be redefined in practical tenderness. People with money could do more than buy titles—they could create systems that listened. Mechanics could be teachers, CEOs could be students of human things, and children could tell the truth in ways adults were sometimes too afraid to hear.

And Eli, who had once been set up as a joke, never became a spectacle. He remained a man who fixed things, who loved with the cautious bravery of someone who knew the cost of small mercies. He built the community program into a place where neighbors came to learn and to teach, where the hiss of engines meant more than commerce: it meant life sustained.

When the narrator of their story—if one believes in such things—looked back, perhaps the most tender truth was this: a mean prank had pushed open a door only for the quiet, patient work of real people to walk through. The world had not been remade in an instant, but it had been altered by choices: Myrtle the receptionist and her Tuesday volunteer drives, Harold’s slow, unperformative apologies expressed in policy, a dozen small sticker-giving moments by a child with curls and a directness all her own.

They did not become perfect. They argued over the right wallpaper for the nursery. They fought about money. Savannah had nights when her anxieties crawled up and made her return to old regrets. Eli, who had always been good at mending inanimate things, sometimes stumbled with the delicate machinery of the heart. But in the spaces between their faults, they kept choosing each other.

Years later, on a porch where a faucet needed tightening and a plant needed repotting, someone would ask Eli how he had become the man who could hold both a wrench and a woman’s hand. He would point, likely, to a gold sticker on his tool chest and say, “Hope.” He would say it simply, as if hope were a screwdriver you could carry in your pocket. He would tell the story of a prank that became a partnership, and how a town, watching, decided to do the small, important things that make life livable.

And Mila, grown just a little but still with the same urgent truth, would one day say at a school show, “I like him,” and mean it in the way only children can—without irony, without reservation, with the pure, practical knowledge that some people are simply good.

That is the shape of the story: a quiet life given the chance, a woman brave enough to follow the small, a father who learned to look, and a town that remembered how to be kind. Not everything in the world changed, but everything that mattered did.

News

Prison Bully Pours Coffee Over the New Black Inmate – Unaware He’s a Taekwondo Champion

The cafeteria erupted into noise—shouts, scuffles, the metallic symphony of bodies that only prisons know. Men who owed Tank favors…

🚨“A Live-TV Reckoning: Rachel Maddow Just Triggered the Most Explosive On-Air Showdown America Has Seen in Years” ⚡

RACHEL MADDOW DETONATES A LIVE-TV EARTHQUAKE: “BONDI, I’LL NAME ALL 35—RIGHT NOW. IF TRUTH TERRIFIES YOU, THEN YOU’RE THE PROOF…

When my grandfather walked in after I gave birth, his first words were, “My dear, wasn’t the 250,000 I sent you every month enough?” My heart stopped.

Vivian, suddenly playing the injured matriarch, bristled. “Now Edward—there must be some mistake. Banks make errors—” Edward’s eyes, a pale…

My Husband Hid A Secret Phone In His Car—What I Found On It Destroyed Everything

I emailed her anonymously at first. “I have information about Julian Mercer. You need to see this.” She replied with…

My husband cooked dinner, and right after my son and I ate, we collapsed. Pretending to be unconscious,…..

My husband cooked dinner, and right after my son and I ate, we collapsed. Pretending to be unconscious, I heard…

Everyone Feared the Billionaire’s Fiancée, But the New Maid Made a Difference When She…

“Let go!” Clarissa hissed, panic sharpening the edges of her voice. The room leaned forward as if the very walls…

End of content

No more pages to load