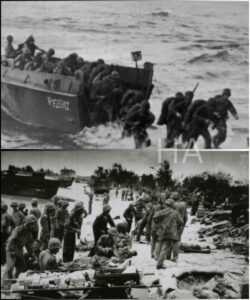

On the morning of June fifteenth, 1944, the sea held the sky and everything was waiting for the sound of orders. Tachsky stood in the bow of a Higgins boat thirty yards from Saipan’s southern teeth with salt on his lips and a list of names he had promised he would not betray. The command was blunt and simple: get in, move inland, find the enemy, mark the coordinates, and then vanish. For days. No support. No rescue if the ocean swelled the wrong way. They were to go where scouts went and return with knowledge of the island’s pulse.

The first wave hit like a paper flag in a hurricane. Machine gun fire braided the surf into spit, and men fell into the froth with the suddenness of old photographs. The beaches were carnivals of hell. Tachsky’s platoon moved through water that tried to pull their legs away and out onto a shore that smelled of powder and broken flesh. By nine-thirty they were three hundred yards inland, where the air thinned into jungle and silence had to be invented all over again.

They found the first pillbox quickly. Sergeant Bill Canuple — who had a history of getting into bar fights and an aptitude for seeing angles — spotted it, a concrete mouth set into a ridge with a machine gun peering like a tooth. To an ordinary unit, the pillbox was an anchor for death; it would halt men and feed them to the guns. Tachsky knew different. He wanted the pillbox removed, but with a hand quick enough to not unsettle their own mission. He had his men deploy a bazooka. Private Marvin Strombo — who had hands like a sculptor’s — put a rocket into the slit and the pillbox coughed flame. The men had learned to be fast and be gone. Within minutes the smoke had cleared and the other divisions walked through a valley where a machine gun had been, and no one knew who had taken it.

By noon the platoon had mapped seventeen positions, called in pronto coordinates to destroy pillboxes and nests with naval gunfire, and they moved deeper. Saipan’s interior unspooled like a secret, revealing caves masked by vines, ridges with guns carved into them, and a tank battalion hidden under a net that looked like a patch of shade. Thirty-seven Type 97s sat like a threat that had a number and a plan. Intelligence had guessed a handful; the forty thieves saw a forest of metal.

Tachsky sat in a crouch under a canopy of ferns and wanted to laugh and wanted to vomit at the same time. The company did not have assets immediately — not shells, not air, not anything that could erase thirty-seven tanks in time. They had six bazookas and six men who knew the rhythm of firing them. Thirty-six rockets to answer thirty-seven tanks. The numbers meant nothing when a man had to choose to act, but for Tachsky the math presented a moral problem. He had recruited men whose lives had been written in minor crimes and sudden fights, men who understood the logic of risk. He also knew what happened if the tanks reached the command post. He could have radioed back and waited for someone with bigger guns, but waiting would mean losing a position, maybe a whole beachhead. He chose the kind of leadership that followed gut and conscience and the quiet arithmetic of what might save others at the expense of themselves.

They moved into position at four fifteen that afternoon. Six bazooka teams spaced like teeth across a semicircle. They were small, nimble, and dangerous. When the engines of the tanks started and the crews came out to inspect maps, the world turned into a thing of engines and heat. Private Herbert Hajes — who had fingers that could steady a rocket like a surgeon’s hand — found a flank and fired. The rocket struck the Type 97 under the turret where armor thinned, detonated, and the tank bloomed into a fireball that lit the jungle like a noon sun. The explosion was not merely a kill; it was a signal. The Japanese infantry near the burning tank redirected toward smoke, believing there was a larger force waiting, and the command post remained untouched. Tachsky’s shot had not only killed men but shifted the battlefield’s geometry.

The price for those benefits was immediate. The muzzle flash gave them away. Machine guns swung toward them like the disapproval of a heavy god. Mortar rounds began to pound their positions. The platoon melted like something that had been taught to be something else. Standard formations dissolved into small teams inching away through vines, moving by hand signals Tachsky had taught weeks before. The night was a long homework of hiding, breathing, listening. Some men kept their pistol but did not fire. They let shadows pass.

By nightfall half the platoon had made it to a prearranged clearing behind American lines. Seventeen were missing. They were either dead, captured, or lost in the endless condition of darkness that had swaddled the island. Tachsky refused to leave men behind if there was breath and chance. He sent search teams at dawn. They found bodies first: Private Donald Evans, shot twice and without dog tags — a detail that made the men glance downward because sometimes the enemy took those tokens as souvenirs of conquest. They found more bodies later; some had been executed, hands bound and bayoneted as if some codified contempt gripped their killers.

But the platoon’s tally also grew with those who had survived: men who had clambered through fissures in the earth, who had crawled out and greeted sunrise like those who have been given back. Five men were trapped in a cave system a mile behind enemy lines. Tachsky could signal artillery to roar and make a diversion, but artillery within caves was a poor surgeon. It would collapse passages and possibly bury friend and foe. He chose a faster, dirtier solution: a six-man rescue team that would move soft and small and take the chance. They slipped into the cave under a sky that was indifferent to the details of bravery and came out with weary faces and five comrades who had been listening to the enemy move above them for a night that had felt eternal. They moved toward friendly lines in daylight because waiting would kill the sick among them.

A Japanese patrol found them partway across the clearing. They ambushed with a killing efficiency that made the men swear and then move to a different kind of battle. The patrol died in seven seconds, nothing more than a mechanical act of muscle and training, but it sounded like a bow snapped in the jungle. The noise returned as voices and whistles and the pounding of feet. They ran and descended into a ravine, and the mathematics of geography almost made their story end. The ravine became a box canyon with a rear wall that looked solid until two men found a fissure that breathed. They slipped through a crack the size of a man’s hope and crawled in darkness through a passage that spat them onto the ridge behind Japanese lines.

When they finally returned to friendly territory at two thirty in the afternoon, they were eleven men who had run the island’s teeth and survived. The count was better but still cruel. They had lost six men in those first days and more would be buried in the weeks to come. The casualty rates were high; the number that mattered most in the calculus of the Corps, the one that came up in generals’ briefings, the one that meant lives spared because of their tracking and marking, sat at the other end: some commanders estimated their work had reduced casualties across the division by roughly fifteen percent. That was an odd kind of victory. You could bury ten men and save two thousand. War keeps its arithmetic cold and precise like that.

After that first week the forty thieves — they had become more myth than platoon in some camp mess halls — moved farther inland. They mapped tunnels where artillery lay hidden as if the island had a secret heart made of iron and acclimatized hatred. Their mission required entering caves the size of small churches, a decision that made the engineers who were months away gnash teeth. Rosco Mullins and Marvin Strombo volunteered to go in with the smallest light they could manage and map passages where guns were shifted like restless ghosts. They found howitzers nested inside caverns, magazines stacked with rounds, men sleeping in carved rooms. They listened to Japanese patrols pass within feet and held their breath until their lungs felt like overused lungs.

The most audacious mission came in the ruins of Garapan. The town had been pulverized by bombing, a place where stones leaned against one another like tired men. Tachsky selected four men to join him and told them to ride. Bicycles — Japanese military bicycles left against a crumpled wall — leaned like clustered sentinels. Five men on bicycles in a town that had once been an enemy’s capital would look like a small, harmless blip, a rumor of movement among ruins. They rode through Garapan as if they belonged to some other story, counting troops and supply dumps, weaving past officers who might have waved if someone had bothered to ask for their names. It was an exercise in audacity that tasted like the old streets of home. For forty-three minutes the platoon became the enemy in plain sight, taking notes as if the world were a map they intended to give away.

The cost of audacity is always measured in lives. Over the next three weeks the forty thieves continued to push, to mark, to wade into places hope had not yet touched. They found children forced to jump from cliffs rather than be captured, they saw wounded Marines used as bait, and they collected the kind of memories that do not unclench easily. By July ninth, when the island was declared secure, they had lost twelve men and nine had been wounded. The casualty rate for tachsky’s unit — though lower than the 73 percent scout-sniper average planners had feared — was nonetheless devastating in ways numbers do not account for.

The survivors came home with bent shoulders and pockets full of dust. Some drifted into restlessness and alcohol. The war had carved hollows into their expressions and no lecture could fill them. Frank Tachsky returned to civilian life and settled into the town-light of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin, where he ran the kind of office that taught him new lessons about men and compromise. He became mayor one day because the town liked his reluctance and the way he described storms. He never spoke — hardly at all — about the forty thieves. He kept their stories in a sapless chest at the bottom of a trunk and took them out sometimes at night like an old photograph: the smell of canvas, the scrape of dog tags, a map with ink lines that ran like the memory of a life.

Years folded into more years and the men who survived grew older and more secretive. Rosco Mullins married and taught carpentry, but sometimes he would sit on a stoop and stare at the horizon as if he were waiting for a sea that would not come. Marvin Strombo took a job in a factory, his hands still quiet and precise from the days of careful shots. Herbert Hajes rubbed an arthritis into his thick hands, the kind of ache that was not only a weather complaint but a ledger for old wounds. Many turned to drink or to silence. A few, like Tachsky, built a life with public service to help forget the private ways in which grief had sutured them.

After the war, official recognition for the sort of work the forty thieves had done was slow and awkward. Military taxonomy is a bureaucracy that likes its boxes neat and labeled. The scout-sniper platoon was an experiment initially, and it stayed a rumor in some officers’ offices for decades. There would be later honors, after the world paid more attention to the quietly effective work of small, specialized units. The tactics the platoon used — deep reconnaissance, independent operations, silent killing traded for information — would thread into the DNA of units that would later be called special forces and, much later, Navy SEALs. Those men had not invented courage; they had been shaped by circumstances and a commander who trusted the calculus of their survival instincts. But influence is not the same thing as fame. They were instruments whose music was not always acknowledged.

Frank died in 2011 and his son Joseph found the footlocker behind an old bureau in the attic, a chest of small bones and heavy paper. There were maps with inked coordinates, a camera with negatives, dog tags, a ribbon with a name, and a pair of boxing gloves that had belonged to a man who used to hit things because he could not ask for help. Joseph had grown up with stories of his father’s mayoral prudence and the quiet way he folded his newspaper. He had not been told about the forty thieves. He sat down with a lamp and the postcards of the war and read until the paper blurred.

Reading the maps, Joseph saw more than coordinates. He saw the geometry of a moral calculus that had been painfully simple: fifty men could not cover an island but they could find the places where the island meant to kill. He saw the baked mud of ravines and the names of men who had been reduced to commas in the public record. He found, too, letters — a small packet bound in twine, written in a hand that shook when it told of nights that tasted of rust. One letter was addressed to a boy, a small note about not letting the memory of violence make him hard, to keep his hands open. Another was a map of laughter: places where men had sung when they thought no one watched.

Joseph made something with the chest he had found. He wrote to town historians, to veterans’ groups, and he sat down with the few living members of the platoon who would still speak, and put their words together into a book that read like a eulogy stretched across decades. The process of translation — of turning a history filed under “minor” into a story that people could read around tables — was not just bureaucratic. It was a moral act, an assembly of truth and tenderness.

When the book came out, there were, as is always the case with old soldier’s stories, a few who wanted medals and parades and more clean categories. There were others who wanted silence and the privacy to heal without being prodded. Joseph understood both impulses. He also understood that there was a responsibility to the living. The story mattered less as a means to glorify violence and more as a way to ask what we ask of those we call criminals. He wanted to ask what it meant to give a man a choice: prison or a life that involved risking everything for strangers.

At a small ceremony in Sturgeon Bay, a modest plaque went up on a stone near the harbor. It was simple, a list of names in a clean type, and a single line that said, “To those who were counted cost, and those who counted.” Some families came, others could not bear to witness the names. Veterans from other wars, who had learned their own versions of grief and glory, stood with folded hands. Someone played a trumpet that seemed to forget its notes and begin again with something like a song.

Not all the men who had been called criminals were redeemed in easy ways. Some died clutching ghosts, their sleep interrupted by the smell of burnt oil. A few could not keep a job; too many days in which certain sounds were lethal. The survivors told stories in bars and in the solitude of their kitchens, in voices that hovered between pride and sorry. Several of them found quiet comfort in the idea that somewhere, across an ocean of absent faces, their work had saved two thousand lives. It was a math that made less sense as it filtered into the softer mathematics of love: fathers who had been absent because their presence had been traded for a rifle, lovers who had waited and been given a man different from the one they had married.

The legacy, when it came, arrived as a strange, living thing. Young officers read the maps, the after-action reports, and they began to build doctrines that took heed of the loose, dangerous genius of small units. They taught scouts to think like thieves: to slip, to steal information, to survive on the crumbs they could find. The doctrine became less bravado and more method. Special forces training borrowed the humility of those men who had learned to die softly in the jungle, and the Navy SEALs, years later, would take that DNA into their bones. Veterans of the platoon met with recruits and complained like embarrassed fathers, telling them that bravery is not a neat costume but a messy, daily decision that does not always end in applause.

On the anniversary of July ninth, a small group walked the dunes where the Higgins boats had disgorged men onto Saipan’s beaches. There were only a few: Joseph Tachsky, Herbert Hajes, a lean, quiet man who liked to whistle under his breath; Marvin Strombo, whose hands had a habit of finding shapes in wood; and Bill Canuple, who told jokes that were rough with missing teeth. They carried flags and a photograph in which forty men were squinting into sunlight. They placed flowers at a rock and read the names. The wind wanted to make more of the moment and it did, lifting cloth and carrying the sound south and out to a sea that did not keep scores.

“What do you tell someone who asks why you fought?” Joseph asked once that afternoon, his voice small against the sky.

Hajes shrugged. “I tell them I had a hand on a bazooka and a choice. I tell them I chose to point it at something. People like choices, even small men.”

Canuple looked at the sea. “We fought because it was what was in front of us. We wanted someone’s child not to be killed for something stupid. A fool’s dream, maybe. But people sometimes need fools.”

Strombo rubbed the rim of a flower. “I tell them I found a kind of family I’d never had before. That’s enough.”

Not everyone accepted that easy redemption. A dozen family members of dead Marines wanted more than the explanation that had been offered. They wanted official recognition that might explain why their sons had been ordered into the texture of the island where they were cut out like shapes. They wanted assurances that the men who made war such calculated choices had been honored in kind. The government slowly, awkwardly, accommodated with medals and letters and chapters in books. It did not fix everything. It could not put back into men what the war had taken from them.

There were moments of human tenderness that stole past the scars, though, like light through a crack. A Japanese civilian once came to a later memorial, his hair white as a gull’s wing and his hands folded as if he were praying. He met only a few of the surviving marines, and when he offered a small apology for the suffering of both sides, an old man in a ragged coat took the man’s hand and bowed his head. The exchange was small and private and without the fanfare that often makes reconciliation into spectacle. It was a human hand reaching across a map scarred by artillery.

Frank Tachsky’s son would, in years after the book, find that his father’s footlocker had become an argument no longer necessary to have. People began to read the maps and learn the names and carry them forward. Old men wrote letters to their grandchildren. A New England boy who had been the child of one of the platoon’s youngest recruits asked to see a photograph and when he looked at the face of someone who had been seventeen and later died, he understood a new scale of what sacrifice might mean.

Wartime is a geometry that compresses and widens and often forgets its finer details. When the forty thieves stepped into Saipan’s rain and mud they were not thinking about legacies. They were thinking about a single breath and a small calculation: one man’s life might, with enough risk, save many. It is a monstrous economy in many ways, and yet it ended in human choices. When the men who had been called criminals stood at a small stone and then walked away into the long, ordinary dusk, they left behind more than names. They left a method and a moral problem and a proof that people who have been cast aside can sometimes become the instruments that pull a force through a narrow hour.

At the end of his life, Tachsky sat on a porch in Wisconsin that smelled of lake water and old paint. Occasionally a neighbor would pass and ask if he had ever been a soldier. He would nod and then say little. He had a son who had unfolded his trunk and put the maps into the light. He had the knowledge that the men he had trained had made a difference the way certain doctors save lives by making small, precise moves. He had a conscience that lived with the memory of the men who died under his command and those who had been executed behind lines and those who had been saved because someone decided a bazooka was more useful than waiting.

The island remained scarred and later slowly healed in the way land does when human hands retire from turning it into a battlefield. New trees took root in old shell holes. Fish grew around broken steel. The names of the fallen were written on a stone formed in a language that tried to be tidy about grief.

The larger world, relentless and indifferent, moved on. Wars are like that: entire cultures of grief pile up at historical moments and then the rest of life resumes its small economies and small pleasures. But for those who had been in the forty thieves, for the families who had smiled and cried and the town that would later read their letters aloud, the story remained a thread. It was not the kind of celebrity that a poster of a hero might bring; it was quieter, like the hum of a lamp at midnight when everything else is sleeping.

If there is a final accounting for such acts it is not in medals or monuments. It is in a child who grows up because someone else risked his life. It is in a town mayor who keeps his quiet and in a son who uncovers a trunk and decides that memory must be carried. It is in men who used to be called criminals and later came to be called by a kinder name: veterans.

War makes hypocrites of language. Criminal meant something at the start — a man punished by a system for petty or violent misdeeds — but in the hot calculus of Saipan they were redefined by what they did, not by what they had done on the streets of America. The island asked a question of a small group of men: which small, brutal gift will you give to others? They answered not so much in valor as in a stubborn kind of survival, in a deliberate cruelty to inertia and an embrace of a kind of mercy. They gave maps and coordinates that were not numbers but chances.

At night, years later in the town of Sturgeon Bay, someone would sometimes hear a trumpet and think it was a neighbor. The sound was more often a memory than a musician. In the attic of Frank’s old house, the trunk remained closed, but the maps had been copied and the stories retold, and town kids learned that the man who once walked their streets had led a unit of men who navigated darkness and kept others alive. That knowledge, if nothing else, made the ordinary citizens of the town look at the next man who came home with a limp and a silence and feel the possibility that behind any quiet face there might be a story more complicated than names in a ledger.

They were called criminals once, and for a long time that name clung like a shadow. But names shift. Sometimes they become a kind of shelter. Twenty-seven years after his return, a veteran would sit on his porch and teach the boy across the street how to whittle a piece of wood, passing down an instruction in quiet. You do not need to say the war aloud in that moment — the act itself holds witness. A child will grow into a man who will, perhaps, rescue someone, perhaps not. That is the slow alchemy of history.

Saipan had been a wound. Men bled and died there, and a small platoon of forty men had altered the way a lot of the rest of the world thought about war. They did not become saints. They became witnesses to the fact that redemption is messy and that courage is sometimes found in the parts of people other people had already decided to throw away. In a bright photograph in a small museum case, they looked sideways at the camera, some smiling, some not, and the plaque below read, simply: “For those who were counted cost, and those who counted.”

If you ever find yourself walking by a harbor town and someone tells you a story about a trunk and maps and men who were once called thieves, listen. It is a story about choices made small and large, about the way a man like Frank Tachsky took a handful of men and let them be more than what a badge had said they were. The sea remembers them in a way that is more honest than any ceremony: the waves keep time with the steps men take, and sometimes they return what was taken, not as treasure but as a chance to say their names out loud.

News

The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Trut

The disappointment in his voice carved a wound she knew would never truly heal. “No, sir,” she whispered. “I swear…

“If I share my cookie, will you stay?”—Asked the CEO’s Little Girl to A Poor Single Mom on the Plane

He watched as Haley rocked the baby, watched Laya rest her head on a shoulder that did not belong to…

On Christmas Morning, My Daughter Said: “Mom, Drink This Special Tea I Made.” I Switched Cups Wit…

Mary’s body didn’t feel like it had been touched. In the hours after Richard got home, she felt no dizziness,…

German Child Soldiers Braced for Execution — Americans Brought Them Hamburgers Instead

When the guards returned, they carried crates. The boys’ shoulders tensed in unison, ready to collapse under the weight of…

Prison Bully Pours Coffee Over the New Black Inmate – Unaware He’s a Taekwondo Champion

The cafeteria erupted into noise—shouts, scuffles, the metallic symphony of bodies that only prisons know. Men who owed Tank favors…

🚨“A Live-TV Reckoning: Rachel Maddow Just Triggered the Most Explosive On-Air Showdown America Has Seen in Years” ⚡

RACHEL MADDOW DETONATES A LIVE-TV EARTHQUAKE: “BONDI, I’LL NAME ALL 35—RIGHT NOW. IF TRUTH TERRIFIES YOU, THEN YOU’RE THE PROOF…

End of content

No more pages to load