In Pat’s view the turning fights were a slow death: time elongated, decisions muddled, the advantage swallowed by patience. In a dive the decision loop collapsed. You saw, you acted, and the enemy could not create the buffer that doctrine adored. It was ugly and it needed nerve, the precise combination of courage and judgment that could not be learned by rote between tea and the evening post. The older pilots mocked him over port. The younger watched and learned in silence, because when a man returns with fewer bullet holes in his skin than his mates, questions are asked in whispers instead of lectures.

The day the German sweep formed off the French coast, the sky was hard and blue enough to hurt. Intelligence had flagged a large operation; the Germans meant to draw the RAF and bleed it. Every available squadron climbed. The briefing repeated, as it always did: climb, engage, protect the bombers. Pat listened and then climbed as ordered, but when the merge came and he saw the arrangement of 109s and heavier Focke-Wulfs waiting in staggered altitude like a layered trap, he saw something else — a machine waiting for a certain kind of prey. The Spitfires below were in Vicks of three, wings too close, eyes too distracted by keeping station. He could feel the trap in his bones.

When the signal came for standard attack, Pat broke away. Formations, he believed, were shields until they became cages. He pushed his stick forward and the Spitfire became a stone, the world a blur of wind and instrument needles. The plane shuddered with the speed, controls grown unusually tight. The altimeter unwound as if someone had grabbed it, the engine screamed. Warnings flashed in the edge of his vision — structural limits, vibration, the thing that all pilots fear most, the knowledge that their machine might not survive their decision. He ignored the warnings. He dove into the center of the Luftwaffe’s arrangement.

The first pass was surgical. He closed on a 190 toward the edge of the formation, centered the gun sight, and burned a two-second burst into its flanks. The German rolled, smoke spitting, then surrendered the sky. Pat zipped through the formation and pulled up, climbing at an angle that made his lungs ache. The surprise had already started to rot their coordination; the Germans had not expected a Spitfire to drive into them like a spear. He picked a different target the moment his energy allowed and dove again.

For the next four minutes he would operate at the edge of both his own body and the Spitfire’s design. Time compressed until each heartbeat felt like a drumbeat in his jaw. He dove and climbed and dove again; every pass was a lightning strike, a two-second conversation with fate where the language was gunfire and the punctuation the small explosion of another fighter falling away. He stitched the sky with tracers and saw the geometry of it in a way no lecture could teach.

By the time his fuel gauge wavered and the engine began to cough, he had claimed kills — confirmed and probable — in a number that made the others look at him as if they had been miscounting reality. He landed on fumes, the Spitfire groaning and warped from strain, the ground crew pouring out like a flock of worried men. His hands smelled of oil and something metallic. He raised eight fingers, then paused and corrected himself to nine. He had forgotten the first one; the brain misfires under shock and adrenaline.

There was no fanfare, no trumpets. The squadron leader did not yell, though the men were looking for words. Instead he asked Pat to explain what happened, step by step. Pat explained in simple terms: choose high, strike with surprise, use speed to avoid counterattack, disengage. He sketched angles in the dirt with his boot. He spoke like a farmer listing seasons or a mechanic listing parts; there was no bravado, only clarity.

The ripple began quietly. Other pilots came to the ready room and asked exactly where to start. Trainers at the flight school opened a space to teach energy tactics. A doctrine that had been inviolate for so long unfurled like a map with new routes. The old guard grumbled. They pointed to the planes that failed and to the young fools who tried to imitate without judgment. There was truth in their complaint: boom-and-zoom required a combination of judgment, situational awareness, and the ability to tolerate the uncomfortable close to the limits of structure and nerve. Yet where the doctrine once killed by ritual, the new approach saved lives by changing the terms of engagement.

It was not only the kill count that mattered. It was the message. Men who had clung to the safety of dogfight orthodoxy watched a single methodical soul carve through a formation and survive. He had not been theatrical; he had not staged a solitary myth. He had adapted principle to reality. When a tactic returns men to their families instead of to the memorial roll, it becomes a contagion.

He kept flying after that day, not as a demagogue but as a man who preferred work. He did not tour in triumph. He never courted the press. He continued to stroll the wing before and after flights, glancing down at rivets and asking the plane if it had behaved. With each sortie his kill tally crept higher. Other pilots — young, hungry, scared — adopted the tactic with varying results. Some came back with holes that spoke of survival; some did not come back at all. The technique demanded more than imitation. It demanded judgment.

There were nights when Pat sat alone staring at his hands, the same hands that had once steadied oxen or tightened a fence post in his father’s absence. The war was a field of broken promises and small gestures. Men swapped anecdotes and keepsakes, photographs from a life that seemed incongruous with the roar of engines. Pat had his own little rituals: the slow walk around the aircraft, the counting of rivets like beads on a rosary, the occasional note in the edge of a logbook where he recorded minor mechanical peculiarities. He scribbled lines and numbers more often than thoughts.

When the war’s chaos eased in small theaters, and when the shape of air combat shifted under the pressure of technology and doctrine, the techniques he had used were taught differently. They were given names that sounded technical and academic. Instructors spoke of energy management and potential energy; academics wrote papers that named and measured the phenomena he had exploited instinctively. Doctrine codified what he had done without fanfare. He left the lectures to others. He rarely corrected the papers — he had no taste for scholastic victory. His victory, he seemed to believe, was to give a useful thing away.

In the months after the nine-kill sortie, the squadron told smaller stories about him the way fishermen tell of weather: the time he pulled a maintenance boy out of the path of a collapsed wing that had given without warning; the time he refused to accept a medal, saying the luck was not worth dressing for. There was a photograph that circulated amongst the men — faded and shy — where he stood beside a Spitfire, hands on hips, looking off-camera at something beyond the frame. He was not smiling. He looked like someone who had learned the shape of danger and the mathematics of survival, and found them heavy.

Heroism, in that war, was not measured by medals alone. It was a ledger of small mercies: a pilot who refused to leave a wingman, a mechanic who saved a spark of life through midnight toil, a nurse who insisted on listening twice to a child’s flat laugh. Pat’s legacy would not rest in a single sortie, no matter how dramatic, but in the habit he left behind: the invitation to think, to question, to try a method that looked crude on a chalkboard and dangerous in a mess hall but saved men in the sky.

There was a day in a dim debriefing room when a young pilot asked him how he knew when to push and when to pull back. The pilot had fingers that remembered the throttle and eyes too recent with grief. Pat looked at him as if measuring the distance between two stars. “You learn the sound of a thing and the sound of yourself,” he said. “If you’re honest with both, the plane tells the truth. The trick isn’t in being brave; it’s in being honest enough not to try a move you cannot finish.”

The war wore on. Technology sprinted ahead of the things men knew how to do with it. Yet Pat’s simple geometry — altitude, energy, initiative — threaded through the new machines. Pilots in faster jets would adopt the same instincts, though the instruments evolved and the names changed. The vertical dimension became an argument not between doctrine and chaos but between situational control and complacency. His name did not appear on every list of innovators; history is a sieve. But the students who removed their notes in lecture halls decades later did not argue with actions that kept them alive.

When the war finally breathed its exhausted sigh of surrender, Pat returned to the veld as if to test whether the world had changed in a way that mattered. The orange trees were the same; the wind still smelled of dust and the tang of citrus. He walked the farm in old boots, hands used to levers and cables now taking to plow handles. He married a woman named Elise whose laughter could fold open a sun that had long been gray from fatigue. She liked that he did not talk about the war often; she liked, too, that he cleared his plate at supper and talked about rain, about seed, about the shape of the day. The war had taught him to measure the small things with solemnity. He left the loftier matters to others.

At home there were nights when he would wake and write single lines in a thin notebook — a phrase about an engine note, an angle that had saved a friend, a boy’s face in a photo who had not come back. He burned unmatched letters; he sent others in neat envelopes to mothers and fathers who had requested nothing but acknowledgment. He never sought a monument. The idea of a statue felt performative. He favored instead a quiet ritual: teaching local boys who dreamed at dusk to fly gliders, not because they would likely become aces but because they should know the habits that keep a pilot and a man honest. He taught them to listen to the machine and to themselves, to feel the aircraft like a companion. The boys called him “Pat” and sometimes “Old Marm” affectionately. He had no taste for the heroics that appreciate a microphone. He preferred a chalkboard and the smell of canvas.

Years later, when one of those boys — gray around the temples and careful with the memory of nights over the Channel — visited the farm, he found Pat in a field of tall grass, teaching a small child how to whittle a stick. The visitor asked him whether he regretted anything. Pat looked at the boy, then at the sky, then at the dirt under his boots. “Regret is for things you might have fixed,” he said. “I have memories that ache. That is different from regret. We did what we could. Sometimes that was clever; sometimes it was simply stubbornness. Both are useful.”

The younger man pressed, because men of that age are never satisfied with simple answers. “If you could do it again, would you fight differently?”

Pat paused. A hawk circled over the far fence, a small dark dot against the blue. “No,” he said finally. “I would probably wear a different coat.” He smiled a small, private smile. “No. If I had to, I would choose differently where I could. But the principle is the same. You act with what you know in the moment. You own the consequences. If you’ve learned something useful from it, pass it along. That’s how the world tilts away from harm.”

He kept his hands in the work of the farm and in the teaching of young pilots. He wrote an odd, short essay once for a flight journal, not for academic prestige but because an old friend begged him gently. He wrote about the concept of initiative and energy without citing models or calling names, the sort of practical wisdom that made instructors nod and then rewrite it into diagrams. It was short and unadorned. The journal printed it. Pilots in later conflicts would read those few paragraphs and swear that they kept them under their helmets.

In ceremonies years later, when the old men met and swapped faded photographs and debates about tactics, his name came up sometimes as something almost mythical — not the conquering hero in the operatic sense, but the quiet man who changed how people thought about a terrible thing. It is easier to raise monuments for battles and big names; it is quieter to keep alive the memory of a method that saved ordinary lives. And that, perhaps, was the shape of his modest pride.

There were nights, still, when the campo of his dreams was a blue bruise of tracers and the smell of burning fuel, and he woke with hands pressed to his chest as if to assure himself that the house was not a cockpit. Elise would lift a blanket and find him like that sometimes and hold his shoulder until the pulse eased. She understood the ways trauma and habit blurred in a man who had learned to trust his senses before they trusted soft instructions. She also understood patience and mercy. Theirs was a marriage sober and practical, with small mercies given freely.

The war did not end with the comfort of tidy endings. There were men who never forgave themselves for moments of cowardice or hesitation; there were families that never again ate in a certain room without remembering a son; there were communities that became hollow through absence. Pat taught by example that healing is a series of small returns: showing up, naming the sorrow, teaching a child to listen for the engine, greeting a neighbor who had lost a young man with the same measured respect he would offer any loss. There is a kind of kindness in ritual that stitches back together the ragged edges of grief.

In the end, the measure of his life was not the nine kills, though the story of that day became legend and was taught in dusty staff college rooms for a generation. It was not the medals — he accepted a few, reluctantly — nor the notice of historians who used him as a footnote to a larger text. The real measure, if there must be one, was in the way he passed along something useful: the insistence that rules are tools and not scripture, that the world changes and thinking must change with it, and that courage includes the willingness to bear consequences for experiments in survival.

The boy who had once learned to listen for engine notes grew up to be a pilot and then an instructor himself. When he told a new class about a method that had saved scores of men, he did not invoke thunder. He did not speak of glory. He drew a simple line and pointed to the angle where initiative met physics and said, “Listen.”

Many years later, at a small gathering, a man — older now and with a slow sort of dignity earned by sustained attention to small things — spoke about one more quiet item in his life. He told, with an easy rhythm, about the way a Spitfire had once been a stone and how it had cut the sky up into safe places for men who still had mothers at home. There were now grandchildren at the edges of the room and a small boy who chewed his knuckles and listened intently. Elise had passed away the winter before; the grief had been as silent and steady as snowfall. Pat, whose life had once been a string of engine noises and altitudes, had learned to be companionable with simple loss.

At the end of the evening, as men began to drift away and the lamplight painted the table with tired halos, the old pilot took the small boy’s hand and led him outside. The night was clear and a few stars pricked the dark. He pointed to the sky, the way a teacher points to the part of a map a student should memorize. “You can be brave in many ways,” he said. “Bravery isn’t always the loud sort. Sometimes it’s the stubborn, quiet kind that chooses a path when everyone else is clinging to a map that no longer fits.”

The boy nodded, solemn with the gravity of the moment. He asked the question children ask of men who have weathered storms: “Were you scared?”

Pat laughed softly, the warm sound of a man finally comfortable admitting something small and honest. “Every minute. Every time I moved the stick. Fear’s the measuring stick. Courage is what you do with it.”

The boy did not fully understand then, not as he would years later when his fingers had known a control column and the taste of metal and exhaust. But the words sat in him like the seed of a practice.

Years later still, after Pat’s hands had been stilled by time itself and the farm smelled of harvest and quiet, pilots would sometimes stand and tell his story. In lecture halls and at small reunions, they would speak of a man who dove like a falcon, who turned gravity into armor, who refused to wait for consensus while men died. They would pass along the lesson: that doctrine must breathe, that rules cannot be worshipped when they become instruments of death. Some would come and place a single orange in the dirt near the farmhouse where he had taught those local boys to listen to engines. A small monument might appear on a quiet knoll, but the real memorial was the tactics that saved lives and the small, stubborn practice of teaching what one had learned.

If a legend must have a last line: he had once been mocked in an officer’s mess as a caveman, and the men who had mocked him later borrowed his lines, rephrased them politely, taught them in lectures, and wrote them into manuals. Pat smiled at none of it. He had wanted only to fly true, to speak plainly, and to pass on the useful things. In the end that was enough. The nine-kill sortie mattered in the way a single bright strike can reroute a river. But it was the habit of thinking clearly under pressure, the courage to act on what you know, and the willingness to teach the next man that marked the humane arc of his life.

In the quiet that comes after engines rest, people who learned from him — and through him, a generation of pilots — kept a rule that might be worth keeping in other times: listen to the machine and listen to yourself. Act without waiting for perfection. Be honest in your limits. Teach the thing you learned without insisting it be worshipped. Pass it on.

Those were the things he gave away. The sky over the Channel could not forget him. The men and women who flew after him kept a little of his logic in their helmets, and through their children and their students, his lesson still rippled. It was not a monument the size of a cathedral. It was the gentler sort of architecture: the careful construction of small uses that preserve life. That, in the end, is a human thing — both ruthless and merciful — and it was the measure of Marmaduke Thomas St. John Pat.

News

Single Dad Fixed the CEO’s Computer and Accidentally Saw Her Photo. She Asked, “Am I Pretty?”

It was Victoria. Not the steel-edged CEO, not the woman who strode into boardrooms like a pronouncement. It was a…

They Set Up the Poor Mechanic on a Blind Date as a Prank—But the CEO’s Daughter Said, “I Like Him”…

His shoulders eased as the first slice warmed his hands and the kitchen’s garlic reached his nose. He had given…

“OPEN THE SAFE AND $100M WILL BE YOURS!!” JOKED THE BILLIONAIRE, BUT THE POOR GIRL SURPRISED HIM…

She slipped into a vent that brought her out in a corner office smelling of leather and citrus and cold…

Single Dad LOSES job opportunity for helping an elderly woman… unaware that she was the CEO’s mother

“We have a strict policy,” the receptionist said, the kind of reply that had been rehearsed until it lost the…

The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Trut

The disappointment in his voice carved a wound she knew would never truly heal. “No, sir,” she whispered. “I swear…

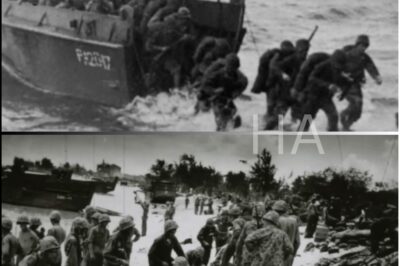

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

On the morning of June fifteenth, 1944, the sea held the sky and everything was waiting for the sound of…

End of content

No more pages to load