Walter tried to steady his breathing. He’d seen newsreel footage of Panzer fours: boxy silhouettes, thick armor, a feel of certain death that they carried around. The Sherman’s 75mm gun had been built for mobility and support; it was not a dueling weapon. They had no illusions. The math said four Shermans to every Panzer. Reality said four Shermans for one Panzer sometimes became a bad joke minutes after it was told.

“Pete,” Miller said, “try to pin them. Walter, you know the drill. Load on my mark.”

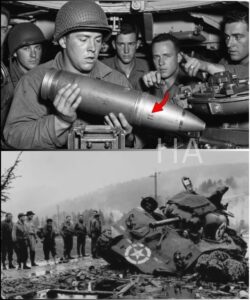

Walter glanced at the ready rack. Twenty shells. Thirty-eight pounds each. He felt the weight of the first one against his palms and it was like lifting a small, stubborn child. His right shoulder whispered a complaint that went sharp and brief. He tried to think of the motion they’d practiced: face the breech, two hands on the shell, line it up nose forward, ram it home. It was a simple, four-second dance if you were on a range under Fort Knox’s forgiving sun. The turret rocked slightly as Cruz eased the Sherman back into a shallow fold in the land.

He took the shell with both hands and tried to turn. His right arm refused to cooperate. Pain cut, precise. His fingers tightened but they were a clique of muscles that could not lift into authority. The shell wobbled. Pete swore. The Panzer silhouettes moved like shadows under a shared sun.

Walter could feel his heart in his throat. Muscles had an interesting way of answering fear with stubbornness. There was an animal-thin part of him that wanted to run headlong into the hedge, tear himself away from something that smelled of hot powder and fate. But a mechanic is a man of tools; he knows how things move. He could feel the breach beside him, warm with the promise of fire. The turret held him.

Desperation is not a thought; it is a verb. He let go with his right hand and turned—because he had to, because the alternative was to fumble and have someone else die. He turned his back to the breech and reached behind with his left hand, fingers sweeping the hot rim like a blind man searching for a familiar handle. The shell’s nose met the chamber. He guided it backward, a motion that made no sense in manuals.

He rammed.

The breach caught and slammed. The gun fired, a sound that reconfigured the inside of the Sherman and sent smoke and cordite into his face. Recoil kissed his back like a billeted lover. Pain bloomed, raw and immediate, but also, startlingly, there was a clean confidence in that motion. In the cramped space, his elbow did not catch on the gunner; he did not collide with the traverse wheel. The arc of his body needed less width. His muscles, bent and anchored, generated more force.

Three and a half seconds. The gunner fired again. The second shell was the same. Three seconds. The third came faster. Two and a half. The fourth—two seconds flat. He felt like a craftsman who had found a better tool and, for the first time since the accident, felt useful in the way that counted.

They hit two of the Panzers before one of them tucked behind a tree line and the rest backed away like wolves that had underestimated their own size. The engagement stopped in four minutes. Walter’s back was black with powder, his shirt a map of sweat. The hatch opened and Miller crawled down and looked at him like a man seeing something he’d been told is impossible.

“How fast?” Miller asked.

The gunner, still staring at Walter as if the man had grown a second head, answered. “Two point eight on average, Sergeant. Sometimes less.”

“You did that with your back to the breech?” Miller asked, incredulous.

Walter said nothing because there were no good words. “My shoulder,” he offered finally. “Right one’s gone on me.”

Miller was quiet in a way that had gravity now. He could have reported the violation. Technical Manual 9-731A did not forgive turning your back on a breech. It insisted upon facing forward, both hands on the shell, eyes on the rim. It contained lists of accidents and three documented cases where improper loading had resulted in catastrophic failure. Those were not small things. But the manual did not smell like smoke and survival. The manual did not have men to keep alive.

Miller looked at his crew, at Rosie’s interior that smelled of hot metal and cordite and his own tired breath. “You doing that again?” he asked Walter, and it was not an order—yet.

Walter shrugged. “If you want us to die slower, I’ll try anything.”

They did it again. And again. Where the standard method required full extension and the fragile arithmetic of triceps and risk, the backward method used ankles of bone and the body’s big muscles. It was like shifting from trying to open a stuck door with the tips of your fingers to using your shoulder and weight. In the tight profile of the Sherman turret, turning his back narrowed Walter’s silhouette, removed collisions, and let the loader use his dominant hand unopposed.

Word passed like a rumor—which in war is often how truths that can kill contaminate the water—moving from hatch to hatch, tank to tank. Other loaders tried the motion on their own, at first out of curiosity, then necessity. A left-handed loader who had been fighting with the right hand’s awkward geometry found that his speed improved. A right-handed loader discovered it felt natural too if you adapted. They steamed shells in times no one had been able to count without tape, minutes that could mean the difference between a clean hit and a tank that lit like a tinderbox.

The fourth armored division kept losing tanks at a rate that made the ground ashamed. But the crews who adopted Walter’s method began to come back more often. A tank that could get three, four shots off before a Panzer found range and fired had a chance. The kill ratios the generals had accepted as math began to go askew. Where a Tiger had once made a field into an epitaph, Shermans using the backward load method started to hunt.

Sergeant Miller made the choice the quiet men make in the middle of bad things: he kept his mouth shut and taught. He called Walter into the mess tent and had him demonstrate, hands shaking from the strain and the rhythm. Miller timed them with a stopwatch and they practiced until hands became instinct. No official paperwork passed this way; there was no need. When a man’s life depends on one small motion, you either rise to it or you are not told about it twice.

Lieutenant Colonel Kraton Abrams—Abrams with the eyes like a man who never forgot a line of a map—was not a man to be fooled by rumor. He liked the smell of results. When he walked into the exercise area on September 23rd and watched a loader turn his back and finish in under three seconds, he stopped and called in Miller. Abrams asked questions not to punish but to understand. He listened without interruption to the story of dislocation, improvisation, and an odd kind of success.

“Does it work better than the manual?” Abrams asked finally.

“Sir,” Miller said, “it’s faster. It’s safer under fire.”

Abrams was silent for a long time, measuring what had been uncounted. The battalion commander did not have the luxury of manuals when his men were dying. He had to choose between doctrine and life. He chose life.

Within forty-eight hours, the 37th Tank Battalion had a new informal drill. Walter stood before replacement loaders like a teacher with grease on his knuckles, showing the motion step by step. He watched men practice—left-handers and right-handers both—and he felt a strangeness in his chest that had nothing to do with fear. It felt like gratitude mixed with the odd embarrassment of a man who did something by accident and had somehow stepped over the line drawn by rule and into the wide world of effect.

Then a rumor reached higher, the kind that carries when numbers change and admirals lean in: General Patton asked what had happened when he saw the improved after-action reports. Patton did not waste time. He was not interested in manuals unless they matched results. He came down to see for himself, stood in a provincial field under a blue sky that looked like a map, and timed three loaders. 3 seconds. 2.88. 2.9. He smiled like a man who had won a small argument with fate. He gave an order: Third Army would adopt it immediately.

It spread like a tide afterwards. The manual did not change. It couldn’t in the heat of the moment and men a step away from discipline found themselves measured by a different standard: survival. Now there were manuals that discussed minutes and chance, but there was also a body language that moved through crews and training tents: turn your back, feel the breach, guide the shell, ram with your shoulder, step clear.

Walter never imagined it would change anything beyond the inside of Rosie and a series of datelines that read like screaming headlines: Sherman kills Panzer. But it did. The kill ratios shifted. Units came back with fewer smoking hulks. The men who had been taught the motion in a tent by a sergeant who had chosen to keep someone alive watched colleagues stay that much more human.

Later, it would be said—that the backward method saved hundreds of lives, that it was taught at Fort Knox, that it traveled to Korea and Vietnam, that even the Abrams had a memory of the motion in the muscle. Historians would write papers and estimate the lives saved. But in those small, green moments around Araort, what counted was a man whose shoulder was telling him he could not do things the right way and decided to find the right way that the manuals had never foreseen.

After the war, Walter went back to Detroit and to the Ford plant and to a life that smelled of stamping and coffee. He married a woman named Margaret who liked bread done crisp on the edges and who could make a Sunday chicken taste like a benediction. He had three children who thought of war as something their father had in a photograph: a place where a man could be brave or foolish, depending on which version they chose to hold up.

He never sought recognition that the army would not have given him; the army does not issue medals for violations of regulations, even if those violations tilt the balance toward life. In quiet hours, veterans would come to his funeral in 2004 and stand in a circle the size of a small country and say, without flourish, thank you. They were men whose fingers still knew the reach and the pull of those shells. Some of them had never met Walter until his coffin was a wooden truth, but they had learned the motion from men who had learned it from him. The motion had the strange economy of gratitude: it passed from hand to hand, like an offering.

If anything about him was heroic, it was not that he had done something brilliant—he had not invented the engine or its gun—but that he had been, in a way, willing. The war needed willing people and doctrine; doctrine needed willing people too, especially those who could find better ways in the small dark spaces of necessity. To Walter, the backward loading was not a drama. It was an answer to a problem that the manual had named without naming its marrow: human bodies are not all symmetrical, and the most efficient textbook is sometimes the one that a man’s back writes with sweat in a night of danger.

There is, in every story that lasts, a kernel of human conflict that is not about victory. For Walter, the conflict had been internal at first: the ache in a shoulder, the shame at being less than what others expected. There was also the external, the sergeant and the men and the machine to consider. He had to live with knowing he had broken a rule and saved a man at the same time. That learning shaped him more than any battlefield glory could. It taught him the humility of small solutions.

Years carried Walter across a life that held its own kinds of weather. Ford paid him to teach men the art of brake drums and piston rings; war paid him only in ghosts and in a few good friends who would always know a look. Margaret died before him; that pain was a quieter kind of battle. His children made lives that were not like his, some near the river, some farther. He would sit in his chair and listen to the radio and let the days be a kind of measured peace.

When the historian knocked at his door in the 1990s, Walter treated him like another courier of the past. The man had a notebook and a hope and did not seem fussy about pedigree. He asked questions that pulled out the muscle and memory off the shelf. Walter told the story as best he could. He described the weight of a shell as if it were a living thing, the smell of cordite, the taste of the air after a gun fired in a hedgerow. He spoke of Miller and Pete and Cruz—names he could not forget—and of the odd, raw act of turning his back on a set of instructions because his shoulder had other ideas.

“You changed how tanks were loaded,” the historian said, as if it were a conclusion. Walter laughed the way men laugh at accolades they feel they do not deserve.

“No,” he said. “I broke some rules when I had to. I didn’t change anything on the paperwork. People just stopped dying as much after that.”

The historian wrote his paper. He sent it to journals that liked this kind of human arithmetic: two seconds shaved off a load time, multiplied up, meant hundreds saved. He called it an innovation of the front lines. He wanted to name Walter—place the man in a paragraph and a footnote and a date. Walter was not bothered. He liked the idea that a thing he had done in panic and pain had carried forward into other wars and other tanks. If it had meaning, it would be in those hands that did not fumble a shell beneath crossfire.

There were, of course, costs to bending rules. Manuals exist because of caution and the memory of bad things. Turning one’s back to a breech was dangerous; you could misalign a shell, you could cause a jam, and there were stories of catastrophic failures—loud, ugly things that ate men. Walter’s backward method was not a universal cure. It required judgment and a careful hand. That’s the other thing about the human element: we must remain, even in invention, ethical in our use of it.

The humane ending to the story, if you allow one, is not a neat medal pinned on a chest at a public ceremony. It’s a small meal shared in an old kitchen with the smell of newspapery gravy, a sister-in-law’s gentle teasing, the three children whose faces at his funeral carried the clean lines of sorrow and pride. It’s the way men who learned at his side would come to his grave and say nothing, sit on the low stone and tap the palm as if counting the beats of a heart.

When the museum at Fort Knox put Rosie in a glass case, they preserved the interior like an altar to the past. Visitors stand inside the Sherman’s confined hull and understand. The placard lists armor thickness and engine horsepower. It does not mention Walter. Museums, for all their duty to detail, love the grand narrative: tanks and doctrine and dates that look like banners. But people who know will, quietly, press their palm to the glass and imagine the narrowness and remember, in the way memory does, the palms and the physics and the simple efficacy of an act done to keep breathing men from getting too used to death.

That is the thing that makes this a human story: not the tactical advantage, not the numbers improved in some sterile report, but the small, embarrassing, miraculous truth that a 22-year-old mechanic turned his back on a breech and made a motion that kept a crew, a number of crews, alive.

“What kept you going?” a reporter once asked Walter in a late-in-life interview, his voice damp with the age of the question.

Walter’s hands were still thick with honesty. He thought about his children and the Ford bench and about the men who’d stood in his burial line and he said, simply: “We were scared. We were tired. We were hungry. And someone had to be practical. If you can do something that helps someone else live, you do it. Rules are for when you have the luxury of not dying.”

He smiled then, and there was no trumpet in it, only the tired smallness of a man who had done right by the people he’d had around him. It was not a hero’s smile. It was a man’s. That made it, for the people who knew how to look, the kindest kind of testimony.

War taught many lessons, none of them clean. But sometimes, when the wind hits the hedgerow at Araort just right, you can imagine Rosie hunched in the mud, its loader bending with a shell in hand and the man inside turning his back on the manual and toward life. You can imagine a chain of palms passing the motion down, a kind of secret handshake that had no room for pride and a lot of room for mercy.

And that is the way stories like Walter Kowalsski’s travel: not as the triumphant flicker of a single man’s accolade, but as a slow, generous reweaving of the way people survive together, teaching each other the small motions that keep the dark away a little bit longer.

News

Sir, I Heard a Groan in the Tomb” — What Came Out of the Earth Made the Millionaire turn pale

Miles got sick fast. So fast it didn’t feel real. One minute he was sprawled on the living room rug,…

Come With Me… The Millionaire Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kid abandoned in the Road

The dirt road looked like it had been forgotten on purpose. Not abandoned in a romantic way, not the kind…

Millionaire Visited His Ex Wife And Son For The First Time In 8 Years, Changed Their Life Overnight

Michael Harrington had always been good at leaving. He could walk out of a meeting worth millions without glancing back,…

Millionaire Gets In The Car And Hears A Little Girl Telling Him To Shut Up, The Reason Was…

The drizzle had just begun to turn the cobblestone slick when James Whitmore stepped out of the historic hotel, the…

Most Beautiful Love Story: She Signed Divorce Papers, Left Pregnancy Test At Christmas Eve

Snow drifted past the windows of the Asheville Law Office like soft ash, quiet and slow, almost gentle inside. Nothing…

End of content

No more pages to load