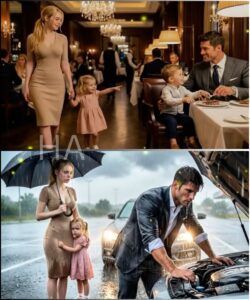

La Lar Rose felt like another world—the marble, the soft light, the kind of place Harper had passed like an island on a map and never set foot on. Sophie saw a man in a gray suit and a boy with a small plastic dinosaur and announced with the solemnity of kings, “There, that’s him, Mommy.” Before Harper could form proper rules about introductions and manners and the art of not interrupting a stranger’s evening, Sophie, in a paper crown, had crossed the lobby and claimed the empty seat beside the boy.

The man rose. He had the quiet of someone used to commanding a room without having to announce it. When he smiled, his eyes softened. “You must be Harper. I’ve heard a lot about you,” he said.

Nate. His name was Nathaniel, but everyone called him Nate. He used to tell people the story of his nephew’s first steps as though it were the founding of a myth. He said his work—architectural design—was about building places that breathe so people could exist more kindly inside them. He had been a widower for a few years; a silence folded around him like an old scarf. Owen, the boy with the dinosaur, made small remarks and watched Sophie with the devotion children have for mirrors.

The evening unspooled like a carefully drawn breath. Sophie and Owen played with crayons borrowed from a neighboring table. Harper worried about menu prices and whether Nate would notice, and then she discovered that he did notice—and when he noticed, it was not to pity but to make room. “Order whatever you and Sophie like,” he said, leaning in. “No pressure. Just here to eat and maybe survive the chaos together.”

That simple phrase—survive the chaos together—scooted under Harper’s ribs and settled there like a warm coin. Conversation began with the expected niceties and then softened into something more candid. Harper told him about the late nights at the rehab center and Mrs. Langford’s sharp wit and softer mischief. Nate spoke about Owen’s obsession with pillow forts and the way the house smelled like failed attempts at bread when he tried to bake. He told her, not with bravado but with a blunt tenderness, that when his wife had died the first years had been a fog. Owen had been the beginning of his return.

By the time they left, Harper’s initial embarrassment had been polished by laughter and two forks turned into makeshift drums that caused a circle of polite applause. Nathaniel—Nate—walked them out to the cab. “I’ll text you,” he said to Sophie. “Ask me if pink cows make strawberry milk.”

Sophie whispered to Harper on the ride home, “Mommy, he laughed when I said pink cows.” Harper’s cheeks flushed in a way that made the cabbie glance at his rearview mirror and smile politely, like the world had allowed her a small, improbable pleasure.

The coincidence of a park visit the next Saturday—Mrs. Eleanor’s planned picnic—was, if not contrived, then certainly arranged by forces Harper preferred to call fate. Nate and Owen were already there with a blanket and a wicker basket. The green afternoon felt like an inside joke. Children invented games whose rules only they remembered. Nate produced mint tea in a bottle because he had remembered Harper wrinkling her nose at coffee on their first date. He brought a pack of hypoallergenic wipes because Owen used to get sneezy in spring. Those small attentions—an inkling of observation tuned to care—began to stitch themselves into Harper’s life in a way she had not planned.

The things that mattered with Nate were not showy. He didn’t arrive with presents that announced their presence in angles and lace. He arrived with the patience of someone who had learned how to stay. He filed forms and fixed small troubles and listened. He filed himself into the margins of Harper’s days like a bookmark.

And yet Harper’s life had a weight that didn’t disappear. She’d been left with Sophie at twenty-three; the memory of judgmental faces, the ex who vanished into morning without a backward glance, sat like an old bruise. Mrs. Langford, one of Harper’s charges—eighty-two, with a diamond brooch and a sharper tongue than most knives—offered a version of this doubt before Harper could finish giving voice to it. “Don’t confuse kindness with affection,” the old woman warned in the laundry room one afternoon. “Men like that don’t marry women like us, dear. They’re not uninterested in hearts; they’re uninterested in strings.”

The words sank, salted Harper’s soft places, and she began to pull back. The safety she had wrapped herself in—a pocketbook of steady electricity and predictable shifts and Sophie’s small hand tucked in hers—felt less flimsy than another attempt at opening to someone who moved in rooms with chandeliers.

So she sent the email. It read the kindest possible thing she could manage: thank you for everything; you’ve made my weeks brighter, but I need to focus on being a mother and on my work. The sending of it felt like stepping off a low cliff. She imagined Nate reading it and understanding. She tried to imagine Sophie’s future with fewer risk lines in it.

Sophie asked in a fragile voice, “Did I do something wrong?” That question landed like a stone in Harper’s pocket and sat there, making her move with a small lurch.

The hiatus was awkward and empty and fragile enough that it cracked at the edges. Then Mrs. Eleanor fell down the stairs. It was a minor accident, but she was bruised and under observation. Harper rushed to the hospital and found Nate there, the timing of his arrival soft as a hand. They settled into hospital chairs and took turns holding Mrs. Eleanor’s paper cup of cranberry muffins.

When Nate said, “You didn’t need to push me away,” he did not sound offended. He sounded tired of the role he had never asked for—someone who had to prove his earnestness. “When I see you,” he said, “I don’t see baggage. I see someone who shows up for the hard work.”

Harper looked at her hands, which had grown callouses from folding blankets and from the constant giving that kept her household moving. She felt small and large at once—small before the half-syllables of possibility, large with the weight of someone who would not abandon Sophie’s small hand. Her instinct, refined by years of care, was to test reality to its edges.

Nate handed her a small box that, when she opened it, contained Sophie’s tiny pink shoes, mended so neatly the worn souls seemed new. “I didn’t fix them because I felt sorry,” he said. “I fixed them because those shoes remind me of the best walk I’ve taken in years.” Harper’s throat worked. It was an ordinary thing—a pair of shoes—but it was the ordinary things that decide the future.

They did not sign their names on a contract that afternoon. There were no murmured promises. Instead, there was a quiet understanding that would become more and more resilient: they cared for each other’s people, and that carried more weight than words.

The days that followed were filled with small, ordinary domestic miracles. Nate learned the names on the recycling bins and where Harper’s favorite mugs lived. He carried a small toolbox and fixed the creaky hinges of Harper’s front door. He arrived on Saturdays with a booster seat already set at the table. Harper began to accept invitations to Nate’s house, the before-gilded space softened by a booster seat and crayon marks on the cabinet. Sophie found her drawing of four stick figures pinned to the fridge and proceeded to claim ownership of the world.

Harper’s hesitations had not evaporated; caution is the handmaiden of a woman who has navigated loss. But where fear ruled before, a cautious hope took root. They tested the new contours of family with a mixture of clumsy tenderness: weekend picnics, library readings where Harper read dragons into the yawns of small children, and Sunday mornings of pancakes where Nate burned the edges and Sophie proclaimed them perfect.

Then, the winter came when the world felt fragile and white. Owen ran a high fever. Nate stayed home with him and texted Harper. She brought a thermos of chicken soup and a stuffed bear named Mr. Barry because some problems still demanded a parent’s hands. Owen, who had been aloof and shy in the beginning, reached out in his fever and took Harper’s hand while mumbling in a dream: “Can you be my real mommy? Then Daddy won’t be lonely.”

Those words stripped away the last of the performances. In the hush of the living room, the snow pressing its soft face to the windows, neither Harper nor Nate offered a retort or a precaution. They simply leaned into the warmth that protects small things. Harper fed Owen spoonfuls of soup. Sophie fell asleep with Mr. Barry tucked into her arms. When the fever broke, it was not with an announcement but with the slow returning of color to cheeks and the lightness of small bodies that had been pressed by illness.

It was not a sudden conversion. Love, when it comes to people with lives and wounds and memos to sign and shifts to keep, is a series of small repairs. Nate showed up one Saturday with a small envelope in Sophie’s backpack—a trip to a countryside farm that was less about the country and more about the promise of unharmed time. They went, and in the golden hour of a hayfield they walked and collected moments. Sophie, with her sticky hair and paper crown, asked with the blunt honesty only children can muster whether this felt like a real family. Harper reached for Nate’s hand and did not let go.

The proposal, when it came, lacked all the grandiosity that often accompanies such scenes in stories. It was honest. Owen, chosen to be the ring-bearer, tripped over the box and made the moment human by laughing in between tears. Nate produced a velvet box: a simple silver ring inside, understated, as if it were an offering rather than an auction. “This isn’t a perfect life,” he said. “But it’s the one I want.” Harper said yes. Sophie screamed and spun, convinced the world had rearranged itself into a kinder shape.

They married in a small garden under a modest sun, surrounded by the people who had shown up for them in different costumes: Mrs. Langford, who insisted on wearing a brooch that had been lost and found in the laundry room of life; Mrs. Eleanor, who had the air of someone who knew the ending before the opening; coworkers from the rehab center who had once been family and would remain so. There were petals and spilled juice and a ring box opened and closed by a trembling boy who took his role seriously and dropped the box in the grass with a face that said he’d done something epic.

The wedding was less a public declaration and more a private settling: two people who had gathered pieces of themselves and put them together with careful hands. It was an assembly of ordinary lives, stitched together by patience and the small, unadvertised miracles of mutual care.

After marriage, their life did not alchemize into the fiction of perfect domestic sitcoms. There were utility bills that required negotiations, nights when Sophie woke up with nightmares and Nate needed to rise and calm her, and days at the rehab center when Harper’s shift left her bones tired and her spirit dim. There were board meetings and deadlines that pulled Nate away and shifts at odd hours that tethered Harper to the center. But there was also a language they had developed for the everyday: the way Nate would place a hand on Harper’s back as she did the dishes, the way she would tuck a note in Owen’s lunchbox like small papery prayers.

Parenting in a blended family is not a tidy matter. Old loyalties wobble and then settle. Owen and Sophie taught each other the limits and expanses of sharing. They learned to trade crayons, to take turns on the swing, to fight over the last pancake and then join in conspiratorial giggles. Nate watched on the sidelines at first and then learned the choreography of being both father and partner to someone who had always known how to do the job of being enough.

There were moments of doubt—Mrs. Langford’s forewarning resurged sometimes as a whisper in Harper’s ear—and there were the harsher tests the universe could throw: a bankruptcy scare at Nate’s company which turned the family’s plans into tattered calendars for a while, a hospital scare with Mrs. Eleanor that required a last-minute trip to the city. In each of those small emergencies Harper found herself acting beside Nate, not behind him. They argued in the heat of bills and decisions, and then they apologized, and then they fixed the faucet while sharing a memory of a small boy playing with a toy dinosaur.

One evening a few years in, long past the first shyness, Harper found Sophie and Owen sitting side by side on a blanket in the park, looking up at the clouds. “Why do you think Daddy fixed our door?” Sophie asked Owen. “Because he wants our home to be safe,” Owen replied, with a sagely seriousness that made them both giggle. That was the kind of thing that made Harper think even deeper about the strange arithmetic of life: care begets care. It is a simple law that does not require proofs, only practice.

Sometimes people ask how you know when love isn’t a temporary shelter. Harper’s answer would be small and peculiarly domestic: when you willingly accept someone else’s small, inconvenient needs as if they were your own, when you find room in your heart for the complex graph of someone else’s past. For Harper, it was in the way Nate fixed Sophie’s shoes, yes, but also in the way he learned the music of her patience and returned it in small acts: a bowl of soup on a heavy night, a hand on a shoulder, a willingness to show up when the weather was bad and nothing spectacular awaited him.

In the end the story did not resolve in fireworks or a single triumph. Life continued, messy and bright. Harper and Nate had days when they loved each other loudly and days when they loved each other quietly. They were sometimes foolish and sometimes brave. They argued about paint colors and grocery lists and sometimes forgot to be romantic in the way movies suggested. But they also taught two children how to be part of a unit that offered more than shelter—it offered steadiness.

On a Sunday in late spring, when the grass had the fresh green of new things and Sophie ran through the park letting a ribbon stream the way wind allows a flag, Harper lay back on a picnic blanket and watched the sky. Nate’s hand found hers and settled there like a bookmark, familiar and warm.

“Funny,” she murmured. “How one little girl in a pink dress pulled me over a threshold I didn’t know I needed.”

Nate laughed softly. He brushed a loose curl from her forehead and kissed the line where hair met skin. “Best wrong turn we ever took,” he said.

Sophie and Owen came back, triumphant and sticky, with pockets full of dandelion seeds and a plan to construct a fort of blankets later. They asked if they could move into the house next door, which was a joke Harper and Nate played with for years and never answered with anything except a new patch of shared laughter.

The rest of their mornings and dinners and rainy nights slipped into a kind of ordinary richness. There were more surgeries of broken toys and fewer nights spent alone. There were the dull battles of money and the acute joy of watching children learn to read. There were regrets that never quite went away, but they softened into an extra color in a painting that otherwise had broad strokes of contentment.

At some point the old brooch Mrs. Langford talked about—once assumed lost to the wash—appeared on a drawer beneath Harper’s bedside lamp. That, too, required a repair: a small hinge mended and a knot in memory untied. Harper learned, in the slow algebra of daily life, that the world returns more often than it takes away if you keep your hands open.

Years later, Harper would sometimes tell Sophie and Owen the story of how everything began: a cream envelope, a paper crown, a little girl’s hand dragging a mother across a restaurant. “It was the best pull of my life,” she would say, and Sophie would look at her with a face lit by a thousand ordinary suns and declare that it was all due to her.

If there is any moral to the life that grew around a navy dress, a gray suit, and a pair of scuffed pink shoes, it is this: families are not only born from grand declarations. They are assembled from the small, habitual acts of people who choose, day after day, to show up. They are built by those who fix what’s broken because they notice. They are created by children who will love you without reservation and by adults who allow themselves to be loved back.

Harper would never claim to have become anyone other than who she always was: stubborn, patient, honest. But those traits, in the company of another who could meet them with equal steadiness, multiplied into a kind of home that held more laughter than fear.

The camera that never existed would have pulled back then: a family under a blanket, two little hands reaching for ribbon, a man and a woman whose fingers looked like they had become a single safety net. No dramatic crescendo was needed. The quiet would have been loud enough.

They did not live in a castle or a tidy magazine spread. They lived in a house that smelled sometimes of burnt toast and sometimes of cookies, a place where crayons disappeared into sofa cushions and the toe of a shoe needed mending. It was, in every practical and profound way, whole. And they were, imperfect and ordinary and resolutely kind, exactly themselves.

News

Single Dad Fixed the CEO’s Computer and Accidentally Saw Her Photo. She Asked, “Am I Pretty?”

It was Victoria. Not the steel-edged CEO, not the woman who strode into boardrooms like a pronouncement. It was a…

They Mocked His “Caveman” Dive Trick — Until He Shredded 9 Fighters in One Sky Duel

In Pat’s view the turning fights were a slow death: time elongated, decisions muddled, the advantage swallowed by patience. In…

They Set Up the Poor Mechanic on a Blind Date as a Prank—But the CEO’s Daughter Said, “I Like Him”…

His shoulders eased as the first slice warmed his hands and the kitchen’s garlic reached his nose. He had given…

“OPEN THE SAFE AND $100M WILL BE YOURS!!” JOKED THE BILLIONAIRE, BUT THE POOR GIRL SURPRISED HIM…

She slipped into a vent that brought her out in a corner office smelling of leather and citrus and cold…

Single Dad LOSES job opportunity for helping an elderly woman… unaware that she was the CEO’s mother

“We have a strict policy,” the receptionist said, the kind of reply that had been rehearsed until it lost the…

The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Trut

The disappointment in his voice carved a wound she knew would never truly heal. “No, sir,” she whispered. “I swear…

End of content

No more pages to load