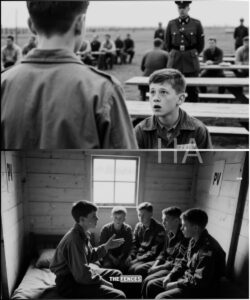

When the guards returned, they carried crates. The boys’ shoulders tensed in unison, ready to collapse under the weight of whatever came next. One crate lid creaked open and the light caught on something red and familiar: Coca-Cola, the name written in a script Eric had seen on posters and in the margins of magazines before the war. The letters were like a joke—bright and curving and absurdly cheerful in the gray field. Somebody had told them, in hurried whispers on rail cars and in the hollow shuffle of bunkrooms, that the Americans were decadent, that their decadence was a thing to despise. Eric had believed all of it. He had believed most of it because believing is simpler than not believing.

Another guard set down a crate thick with frozen meat shaping into patties. The smell—I can still tell you how the smell was—seemed to argue with the gray memory of bread and watery soup. Oil began to hiss and sing on a hot griddle. The sound was small and domestic, the sort of noise you associate with kitchen counters and laughter, not with armed camps and barbed wire.

The boys watched, every muscle taut. Some whispered prayers under their breath in German. Others stared past the guards, into the mountains, committing the measure of snow to memory. Eric thought, absurdly, of his sister’s laugh—short and bell-like—and wondered whether she had eaten berries that spring. The patties sizzled; steam coerced the air into carrying something like mercy.

When the guards assembled the food, the boys remained motionless, as if they had to gather the courage to keep breathing. The first boy received a wrapped burger and a bottle sweating with cold. He clutched it, eyes like a beggar’s. Then another took one. Then another. A guard nodded at Eric. He stepped forward as if into a photograph of himself he’d never seen before: a fourteen-year-old with fingers that had once held a different kind of toy. He accepted the paper-wrapped circle of warmth and the glass that was so cold it bit. For a moment, he did not understand why hands trembled upon the paper; why an eating could feel like trespassing.

The first bite was bewilderment. The beef was rich and strange, seasoned in a way he could not name but that told him of kitchens that had not known scarcity. The bun was soft and the lettuce crisp—luxuries that had become myths three years earlier. He bit carefully at first, to prove to himself that the world still obeyed a geometry of cruelty. But with the second bite his mouth exploded into memory: not of hunger alone, but of something softer, older, a sunlit kitchen in a house that might not exist anymore. He drank the Coke and the fizz pricked the back of his throat like a laugh.

Around him other boys were doing the same. The tension sloughed from their shoulders like a cloak that had been too tight. For a few minutes the camp—if one could call it that—was a long table at which boys with war-painted faces ate like children again. The guards kept their distance, retaining the distance of order and duty. They did not smile wide; they did not make statements; they simply cooked, plated, and offered.

Later, in an interview recorded with historians long after, Eric would say, halting and surprised, that the feeding had felt like a translation. Up until that moment, he had understood the war in a single language—commands, threats, fear. The hamburger spoke another language: it said, perhaps there is room for kindness even in the geometry of conflict. That language was dangerous and fragile; it sat like a single warm stone in a river of ice. To be given a meal was not the same as mercy saved for the dramatic crescendo of a world in collapse. It was something smaller, more potent: a simple shift in the expected texture of human interaction.

But mercy begets curiosity as much as gratitude, and curiosity is a dangerous thing in prisoners. After the feeding the guards repacked crates and cooled the griddle. The boys were marched back, past the sheds and toward the barracks that smelled like damp wood and other people’s sleep. It was as if they had retraced their steps through the same scene but with a different coloration. The fences still frowned with their wire; the watchtowers still stood like questions. Only the boys had shifted in the equation. The weight of expectation had been lifted by something as small as a hamburger.

Inside the barracks, the boys dispersed. Some lay on bunks staring at the planks above, the wood grain like a map to a life they’d lost. Others sat in clusters trading thin jokes, their laughter small and rusty. Eric walked to the fence and sat where the chain link made a shadow like lace. He held the crumpled wrapper in his pocket for a while, then took it out, smoothing the paper with a thumb as if he might iron away memory and leave only the warmth.

Later that day, after guards closed the gates and the dust settled, Eric found a corner note in his chest that would keep time for decades: the idea that the enemy’s hands could make something that smelled like home. He would never confuse a soldier with a monster again. Instead, he learned to live with the complexity of people who could do both harm and ordinary, quiet good.

The war did not end in private moments of bread alone. It ended with headlines, with the collapse of cities and the unraveling of an ideology that had eaten its own children. Repatriation came slowly. Eric boarded a ship in November that creaked and rocked with the same lilting insistence as his childhood trains. Europe unrolled beneath him like a map whose towns lay in cigarette-colored ash. He stepped off into Dusseldorf to a city that blinked in sunlight and rubble. His mother stood in the doorway of an apartment that had survived; she was thinner, older, and the moment of their reunion had the awkward, careful joy of people who had been reset by catastrophe. There were tears that had no proper language—neither laugh nor wail—and they held each other like newly rescued objects.

Eric married a woman from a rebuilt neighborhood and worked as a clerk in a municipal office. He had a son who loved comic books and a daughter who painted her nails a defiant red. He fixed a failing bicycle for a neighbor and told small jokes at team dinners. He built a life of the ordinary kind—work, carpools, birthdays—and the war sat in him like a seam: a place where the fabric had been stitched together but not smoothed flat. The morning in Colorado rarely left his lips. It was a private shard of light he kept in a box.

Years passed, and the hamburger faded into a background cadence of memory. The world grew modern in a way that would have astonished the boy who once believed in the iron language of propaganda. American films entered German cinemas, jazz carried with it an afterimage of possibility, then hamburgers themselves became a symbol of modernity and compromise. In markets across Dusseldorf the scent of sizzling meat could startle Eric into remembering that morning as if it had been painted in the day before.

One autumn afternoon when Eric was seventy, he stood in a market square with his wife and watched a boy shape patties at a street stall. The hands were young and deft, and the rhythm of shaping and frying cracked something open in him. He felt weathered, steadier than he had once been, and yet the smell of the grilling meat pulled him backward with the force of a tide. He ordered a hamburger with the absent-mindedness of someone who has learned how to wear old habits. The vendor wrapped the sandwich in paper and handed it to him.

He walked to a bench where leaves were falling like confetti. He sat and tasted the sandwich. It was different—seasoned differently, warmed by technology that had no place in 1945—but the act itself, the simple act of eating an ordinary meal without worry, felt like a promise he had kept to himself. A promise that it was possible to survive and not let the war become an entire identity.

When he died, in the winter of 2003 at the age of seventy-two, his funeral was small and bordered on the quiet dignity he had carried all his life. His children remembered him as patient, wry, and generous. Some of his friends spoke of the modest acts of service he’d done—fixing a neighbor’s fence, teaching children to read. Nobody, outside of a single archived interview and the soft footnotes of war chronicles, knew the detail of that morning in Colorado’s field.

But because history seldom allows itself to be contained, the story of the hamburgers leaked into the complex weave of the past. A historian—meticulous, patient, the sort who reads the quiet pages others skip—had found an interview and a personnel roster and traced the names of guards to their small obscurities. It turned out that the feeding was not an isolated act; it was the brainchild of one sergeant: James “Jimmy” Mallory, a cook by station and a sergeant by temperament, who had once been a boy with clenched fists and an older brother who died overseas. Jimmy remembered hunger that had the shape of threat, and he disliked the idea of children being told the language of death when they could be relearned at a table.

In the years after the war, Jimmy had kept a photograph of those boys in his trunk, tucked between ration cards and a letter from his mother. He had never intended the feeding to be heroic. It was a small decision that had the geometry of common sense: a way to calm young prisoners so that they would not panic and the camp would not become chaotic. Yet for some of those boys—Eric among them—it became meaningful in a way that defied the sergeant’s practical mind.

Decades later, when old soldiers gathered and memory turned narcotic, Jimmy visited Europe once, with the shallow aim of seeing a place he’d only known in maps and newspapers. At a reunion in a small town, in a church basement heated by a slow radiator, he met a man with eyes like a map and a name that sounded like a childhood. It took time, three letters, and a photograph before an old exchange was set. Names were matched to faces, faces to decades. A slow correspondence grew between lover of kitchens and a man who had once stood in a gravel yard, trembling.

They arranged to meet in Dusseldorf on a gray spring day. Eric arrived with the small bundle of things people bring when they expect to translate memory into language: a handful of old photos, a letter he had written as a boy and never sent, and the sort of brittle curiosity that grows in the chest when a child tries to understand the adult world. He walked into the café that had been chosen for the reunion and found Jimmy standing, hands folded like a man being polite to a warrant. He had the same face, if you could trust photographs—creased, a little softer—but the eyes were familiar: steady, capable of small regrets.

They looked at each other the way two people look across a river they once crossed: with the recognition of landscapes and the absence of certain past terrors. Then they sat. There was a polite awkwardness at first, a need to pad the silence with banalities. Eric told Jimmy about his life: the work, the children, the quiet satisfaction of ordinary days. Jimmy told Eric about the war in a way that acknowledged the difficulty of the subject without demanding confession: about ration cards, about his brother, about the decision to make something that smelled like comfort and hand it over to trembling boys.

“You were looking at me,” Jimmy said finally, voice worn by years. “Not with accusation. Just…looking like a boy who wonders whether men are whole or broken.”

Eric smiled, and the smile was a small, hard thing. “We were taught to believe stories,” he said. “Those stories are not easy to give up.”

They spoke about small things—about how language changes the shape of memory, about the first thing each had eaten after the war (a plate of boiled potatoes for Eric; for Jimmy, a slice of bread that tasted like hope). They did not speak of politics, nor did they offer grand apologies. There was no need for absolution; they carried the history between them. What they did do, with hands that had learned to be cautious, was to place a small, warm thing in the center of the table: a hamburger, not a symbol but a shared reference point.

When Eric reached for his coffee, his hand brushed Jimmy’s. The touch was accidental but bright. It felt, to both, like the closing of a loop: a small human contact that affirmed the complex truth that people are capable of both harm and generosity. There was no moral simplification in the gesture. The war remained as it had been: an atrocity, a catastrophe, a rupture. Yet within that rupture there were choices, and some men had chosen, in small ways, to preserve the humanity of others.

Eric died ten years later, and when his children spoke at his funeral—a routine of eulogies like soft folding paper—someone mentioned a story he’d told once, about a morning in Colorado when the sky was sharp and the air smelled of frying meat. They laughed, a little uncertain, at the incongruity. The story had been small in the book of his life but it carried weight for those who heard: a proof that life could be mended in tiny stitches.

History is made of both monstrous engines and the small acts that slow them. The morning the boys thought they would die and were given hamburgers instead became, in time, a parable about the human capacity for surprise. It taught Eric, and the guard who fed him, and those who later heard the story in the warm hush of later years, that compassion does not require melodrama. It asks only for the courage to act.

In the decades after the war, when children who had once been teenage fighters became fathers and uncles and ordinary workers, hamburgers and Coca-Cola became commonplace across Europe, the very things the boys had once been taught to despise. A quick meal at a stall or a flash of an advertisement became, for many, nothing more than a convenience. Yet for those who survived that long, the smell of grilling meat could still act like an electric switch. It could flip on a memory of fear replaced by warmth, of guards whose faceless orders had been interrupted by the small, intentional act of feeding.

Eric kept one of the glass Coca-Cola bottles from that day until his decay began. He kept it in a drawer between maps and a small tin of buttons. It was a relic without sanctity; sometimes he would bring it out and look at the red script and feel the pulse of a morning that had changed the grammar of fear into something else: a grammar of possibility. He never wrote to the sergeant who’d made the meal. The world keeps its small mercies like ciphers. But when a historian tracked Jimmy down years later and arranged for the meeting, both of them felt less like strangers and more like people who had brushed against each other during a storm.

It would be a mistake to triumphalize the gesture. The war was monstrous; its suffering vast and indeterminate. The feeding was a small correction to a larger imbalance. Yet those small corrections add up; they are the stitches in a garment that cannot be repaired by generals or treaties alone. Acts of ordinary decency—food placed in hands that expect blows—are the quiet daily work that allows survivors to return to their streets and build again.

When Eric’s granddaughter ran through a park and laughed, she had no language for the battles her grandfather had fought inside himself. She only knew the warmth of a grandfather who read to her, who showed her how to tie laces without scolding. And when she grew older and wondered why her grandfather had the habit of lingering at street stalls that sold grilled meats, why he would close his eyes and place a hand over his chest when the smell rose, his daughter told her: there are things some people do that change others’ lives. Sometimes it’s a meal.

In the end, the story of the sixteen boys in the Colorado field is not only about one morning. It’s about the ways small human acts travel like seeds through the seasons of a life. It’s about a child who thought he was marching to his death and instead tasted a burger and a bottle of Coke and discovered that the map of the world had new routes. It’s about a cook who decided, for reasons both practical and tender, to feed the trembling. It’s about the slow architecture of healing, built not by decrees but by the hands that fix broken things in the quiet hours.

This is not a story that resolves itself in neat justice. There is no sweeping redemption that erases the ruin of cities or the lives ended too soon. The war’s deeds remain and will always remain. But within that ruin lives the knowledge that, even in places where cruelty seemed natural and expected, people still sometimes chose to hand over warmth. That choice is not small in its consequences. It can be the hinge on which a single human life—perhaps many—swings back toward the ordinary.

Eric’s son inherited from his father a small, frayed photograph of sixteen boys on a bench—a frozen page with the mountains behind them and an inscrutable sun above. When he held that photograph, he did not feel the inexorable machinery of history. He felt, rather, the simple proof that a world capable of horror is still capable of ordinary compassion. He framed the photograph in his house and often told his children an abbreviated version of the story: how once, in a field in Colorado, boys who had expected death were handed a meal and found themselves alive to astonishment.

The true ending of the story is not tidy. Wars have many endings. The last line, perhaps, is this: that small mercies are not opposites of cruelty but companions to it, fragile as bread and as necessary. The boy who believed the world was a line of shouting men learned, at a bench warmed by sun and oil, that humans are more complicated and more promising than the stories they are told. He lived a lifetime in the light of that learning. He died having kept the memory close, not as a trophy but as a quiet compass.

On some mornings, when the air is thin and the smell of grilling meat curls into the sky, a person who knows better might pause and remember. They might think of a field, of boys with hollow cheeks, of guards with steady hands, and of a sergeant who understood that feeding a child could be an act larger than any order. They might understand, in that pause, that history is made of choices—choices that are sometimes, stubbornly, small.

News

The Maid Accused by a Millionaire Appeared in Court Without a Lawyer — Until Her Son Revealed the Trut

The disappointment in his voice carved a wound she knew would never truly heal. “No, sir,” she whispered. “I swear…

They Sent 40 ‘Criminals’ to Fight 30,000 Japanese — What Happened Next Created Navy SEALs

On the morning of June fifteenth, 1944, the sea held the sky and everything was waiting for the sound of…

“If I share my cookie, will you stay?”—Asked the CEO’s Little Girl to A Poor Single Mom on the Plane

He watched as Haley rocked the baby, watched Laya rest her head on a shoulder that did not belong to…

On Christmas Morning, My Daughter Said: “Mom, Drink This Special Tea I Made.” I Switched Cups Wit…

Mary’s body didn’t feel like it had been touched. In the hours after Richard got home, she felt no dizziness,…

Prison Bully Pours Coffee Over the New Black Inmate – Unaware He’s a Taekwondo Champion

The cafeteria erupted into noise—shouts, scuffles, the metallic symphony of bodies that only prisons know. Men who owed Tank favors…

🚨“A Live-TV Reckoning: Rachel Maddow Just Triggered the Most Explosive On-Air Showdown America Has Seen in Years” ⚡

RACHEL MADDOW DETONATES A LIVE-TV EARTHQUAKE: “BONDI, I’LL NAME ALL 35—RIGHT NOW. IF TRUTH TERRIFIES YOU, THEN YOU’RE THE PROOF…

End of content

No more pages to load