Family Vanished in Death Valley: 13 Years Later, Two Hikers Solve the Mystery

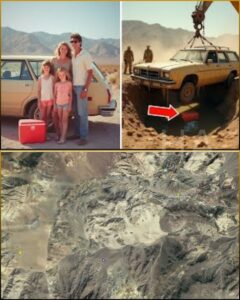

In the summer of 1996, a seemingly ordinary vacation for a German family turned into one of the most perplexing and tragic disappearances in American history. The Rimis-Meyer family—a quartet of travelers from Dresden, Germany—set out to explore the American West, unaware that the journey ahead would lead them into one of the deadliest landscapes on Earth: Death Valley.

The family’s story begins on July 8, 1996, at Seattle Tacoma International Airport. Egert Rimis, a 34-year-old architect with ambitious dreams beyond his native Dresden, stepped off the plane with his 11-year-old son, George Weber. Traveling with them was Cornelia “Connie” Meyer, Egert’s 27-year-old girlfriend, along with her 4-year-old son, Max Meyer. Excitement radiated from the family as they embarked on what they believed would be an adventure of a lifetime.

From Seattle, they flew to Los Angeles, where they picked up a green 1996 Plymouth Voyager minivan from a rental company. Their early days in Southern California were filled with sun-drenched excursions, as they acclimated to the vastness of this new continent. Egert even contacted his bank in Germany to wire additional funds and sent a fax to his ex-wife requesting further assistance—requests that, unfortunately, would never be fulfilled.

By July 22, 1996, the family had set out for Death Valley, temperatures already climbing to a blistering 124°F. The asphalt shimmered with heat waves, and the air seemed to burn on contact. Armed with German-language copies of the Death Valley National Monument Museum guide, they believed themselves prepared for the journey. Rather than spend on hotel accommodations, they opted to camp in their minivan at Hanapa Canyon near Telescope Peak.

The next morning, July 23, they began exploring the park. They visited tourist sites, snapped photographs with a Praktica 35mm camera, and signed the visitor log at Warm Spring Mine, noting in German, “We are going over the pass. Connie, Egert, George, Max.” Investigators later deduced that the pass referenced Mangle Pass—a deceptively simple route on paper but an extremely treacherous path, suitable only for four-wheel-drive vehicles. Their suburban minivan would have no chance.

Along their route, the family visited a geologist cabin in Butte Valley, taking an American flag as a souvenir—a small act of impulsive tourism that would later prove significant in piecing together their movements. As the day wore on and the desert heat intensified, the family faced choices that seemed logical in the moment but would seal their fate. The guidebook suggested a shorter route back to the main valley via Amble Canyon—a rough, abandoned mining track that hadn’t seen traffic in decades. This wrong turn would ultimately transform a dream vacation into a nightmare.

By the end of that day, the family had become trapped in one of the most remote and inhospitable areas of the United States. Without communication tools, sufficient water, or realistic escape options, their situation quickly turned desperate. Their planned return flight to Germany on July 27 was never boarded, and soon, concerns arose.

Back in Germany, Egert’s ex-wife, Haiko Weber, became alarmed when neither her former husband nor her son returned from vacation. German authorities reached out to their American counterparts, but with no crime scene, witnesses, or jurisdictional clarity, the case fell into bureaucratic limbo. The family could have theoretically gone anywhere, staged a disappearance, or met foul play—but the truth remained elusive.

Three months later, on October 21, 1996, park ranger Dave Briner conducted routine aerial surveillance over Anvil Canyon, searching for illegal desert activity. Amid the rugged landscape, he spotted a vehicle in a forbidden wilderness area: the very minivan rented by the German family. The Plymouth Voyager was locked, tires flat, axles buried in sand, and the surrounding terrain showed signs of desperate but futile attempts to move it. There were no footprints aside from Briner’s own, a chilling sign that the occupants had left the vehicle—and vanished.

Inside the van, investigators found luggage, clothing, children’s toys, camera equipment, camping gear, and even bottles of beer and bourbon. The German guidebooks and an American flag helped reconstruct the family’s route, while traces of human waste indicated they had spent at least one night near the vehicle. Temperatures of 107°F by day and 79°F by night suggested that survival would be possible only with ample water and shelter—both lacking in this harsh desert.

The discovery of the van on October 22nd triggered the largest search and rescue operation in Death Valley history. Teams from California, Nevada, and beyond scoured the landscape by foot, horse, and helicopter. Despite their expertise, the desert yielded almost no clues. The only early sign of human passage was a half-buried Budweiser bottle near a bush, suggesting one family member had ventured east from the van.

The official search ended after four days. Around 250 people had combed the desert with no success, leaving the case filed among America’s enduring unsolved mysteries. Over the years, conspiracy theories emerged: some suggested Egert was pursuing classified military technology, possibly attracting clandestine government intervention. Others speculated the family staged their disappearance, inspired by Egert’s musings of relocating to Costa Rica. Foul play theories, too, circulated, including encounters with criminals or drug traffickers—but none were substantiated. To those who knew him, Egert was simply a family man, not an industrial spy.

Years passed. By 2009, 13 years after the disappearance, retired Los Angeles County search and rescue worker Tom Mahoud, intrigued by the case, took it upon himself to investigate. Mahoud approached the mystery like an engineer: breaking the scenario into components, analyzing evidence with fresh eyes, and challenging assumptions made by professional searchers. He theorized that the family had headed south from the stranded van, rather than east or north as previous searches assumed. He deduced that Egert likely sought the China Lake Naval Weapons Center, about 8–9 miles south—a facility he imagined would provide water, communication, and rescue.

Joined by fellow searcher Les Walker, Mahoud began retracing the family’s probable path in treacherous terrain southeast of Golola Wash. Their persistence would finally solve the mystery. On November 12, 2009, they discovered Cornelia Meyer’s remains scattered over 150 meters of desert floor, along with her passport and bank identification confirming her identity. Nearby, a toothbrush, toothpaste tube, and fragments of a small shoe were recovered. Further evidence included a portion of her daily planner and two wine bottles, one identified as belonging to the van.

Over the subsequent days, the remains of Egert Rimis were also located, precisely where Mahoud’s theory had predicted. The terrain was so rugged and remote that prior searches had simply overlooked it. Their route had been a desperate bid for salvation—a journey south toward a military installation, rather than a return to the main valley. Unfortunately, the facility likely had no permanent personnel, leaving the family stranded in one of the most unforgiving landscapes on Earth.

The discoveries ended 13 years of speculation and conspiracy theories. There had been no cover-ups, no staged disappearance, no elaborate deception—just a sequence of logical but fatal decisions made by well-intentioned people confronting a perilous and alien environment.

Subsequent investigations recovered additional remains, though there was insufficient DNA evidence to confirm the identities of the children. Nevertheless, the central mystery of the Death Valley Germans had been resolved. The tragedy highlighted the vulnerability of unprepared travelers in America’s wilderness, where beauty can disguise lethal hazards.

The lessons are clear: Death Valley is unforgiving. Visitors must carry water and food, use terrain-appropriate vehicles, notify others of itineraries, and not rely solely on outdated maps. Even experienced travelers can fall victim to the desert’s deceptive simplicity.

Beyond survival lessons, the story is a testament to human resilience and curiosity. Mahoud and Walker’s dedication brought closure to families who had waited more than a decade for answers. The Rimis and Meyer families in Dresden could finally hold memorials and begin the process of healing.

Ultimately, the story of the Death Valley Germans is a tragic narrative of good intentions and deadly miscalculations. Egert Rimis sought to show his son George the wonders of America; Cornelia embraced adventure alongside her loved ones; young George experienced life beyond Dresden; little Max trusted the adults to keep him safe. Every decision—driven by hope, practicality, or love—was individually reasonable, yet collectively led them into a death trap.

The real heroes of this story are not only the family, whose courage and optimism tragically met the desert’s cruelty, but also the determined investigators who refused to let bureaucracy and the passage of time obscure the truth. Their persistence, fresh thinking, and meticulous analysis solved a case that had baffled professionals for over a decade.

The story of the Death Valley Germans has become American folklore, a cautionary tale about the power of hope, the fragility of human life, and the importance of preparation. It reminds us that missing person cases represent real families and real lives, and that perseverance can eventually uncover the truth, no matter how long it takes.

While the desert keeps many secrets, some—the story of Egert, Cornelia, George, and Max—can finally be told. And sometimes, when hope seems lost and answers impossible, the human spirit proves stronger than the desert itself.

News

Boy Scouts Vanish in 1997 — A Buried Container Unveils a Decade-Long Horror

Boy Scouts Vanish in 1997 — A Buried Container Unveils a Decade-Long Horror It was a July afternoon in 1997…

Police Sergeant Vanished in 1984 — 15 Years Later, What They Found Was Too Horrific to Explain

Police Sergeant Vanished in 1984 — 15 Years Later, the Truth Emerged Too Horrific to Comprehend Sergeant Emily Reigns had…

Hiker Disappears On Trail. Years Later, He Returns With A Shocking Story!

Hiker Disappears on Trail, Returns Years Later With a Shocking Story It was a foggy morning in late August when…

Father and Daughter Vanished on Mount Hooker — 11 Years Later, a Discovery Changed Everything

Father and Daughter Vanished on Mount Hooker — 11 Years Later, a Discovery Changed Everything Sometimes, the mountain doesn’t take…

They Sent the Obese Girl to Clean His Barn — But the Rancher Refused to Let Her Go

The boarding house kitchen smelled of burnt coffee and stale bread. Sunlight slanted through grimy windows, dust motes dancing in…

He Never Touched Her, Until the Day Everything Changed

He Never Touched Her, Until the Day Everything Changed The Prescott mansion stood like a fortress against the Charleston sun,…

End of content

No more pages to load