She had every reason to turn around and drive away. Instead she tested the voice recorder on her phone, took a slow breath, and pushed through the front door. Mildew and something else—sour and sweet, like old candy—hit her first, then dust like the breath of an old book.

The west wing held odd preservation. In the matron’s quarters a bed sat with a quilt half unrolled, a desk with papers still stacked as if someone had gone to fetch a pen and never returned. A bookshelf did not fit against one wall; it was too shallow and too neat. Ruth pushed. Hinges squealed and a second door slid open into a narrow room—no windows, shelves on every wall.

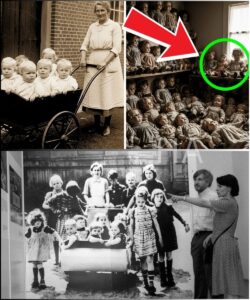

Dolls. Not a scattered heap but an audience of faces, porcelain, cloth, carved wood; some with glass eyes, some with painted smiles that did not reach the painted cheeks. Each was labeled with a name and a date. On the shelf a typed note tacked with a rusted pin read, PERSONAL EFFECTS — SECURED FOR RETRIEVAL — DECEMBER 15, 1968.

Ruth’s fingers shook as she opened a porcelain doll’s dress. Inside, wrapped in tissue, lay a small medal on a chain—a St. Christopher, tarnished but whole—and a brittle note: Tommy Randall, age seven. St. Christopher from Papa. Hold until Christmas adoption.

She documented seventeen dolls before someone cleared his throat behind her.

“Earl.” The voice was a dry scrape. He stood in the doorway like a weathered figure cut out of barn wood, tobacco smell clinging to him. “Should’ve listened.”

“You helped build this room,” Ruth said, the words tripping out of her. “You said—”

“Vernon told us it was for safekeeping,” Earl said. “He gave me the night off. Said he had a special project. Said the children were only going to their Christmas families. Said they’d be back.”

“Back,” Ruth whispered, and the word was an accusation.

Earl’s jaw worked. He told her about the night—December 15th, 1968—of the trucks and the vans. He told her about Sheriff Pike’s press conference about an emergency evacuation because of a gas leak. He told her about Annette, the young woman who had made the dolls with the children, who had been sent home early and found the place empty the next morning. He told Ruth how Vernon Whitmore, the town’s generous benefactor and secret ledger-keeper, had smiled and started buying car dealerships in January with money that had not been in his account two weeks before.

“You got to stop digging,” Earl said finally, and it sounded like a sermon. “Some things don’t want to be found. Vernon—he got what he wanted. He owns half the county and the other half owes him money. If you go poking, they’ll make you wish you hadn’t.”

But Ruth could not unsee the dolls. Inside one she found a little woman’s wedding band, the inside engraved with a name so small she had to press her forehead to the porcelain to read it. Inside another a pocket watch with a dead face. Inside a tiny Bible a petal, dried and pressed. Each possession was a promise: we’ll be back. Each note was a child’s handwriting cramped and earnest.

She drove into town, lodged the photographs at three cloud services, then sat in the library at dawn with Martha, the librarian, and searched microfilm until the reels blurred. The headlines were procedural and dull: Willoughbrook Orphanage Closes; Children Relocated After Gas Emergency. Sheriff Pike’s words were printed like a spell meant to make questions stop. Vernon Whitmore’s expression in the photograph that accompanied the article was of a benefactor who had saved children with a swoop.

“But I saw trucks,” Martha told her. “Three moving trucks and two vans, midnight. Drove right past my house, split at the crossroad and headed different ways.”

The ledger in the hidden room had 43 names, ages three to sixteen, and underneath one hurried, slanted line: SPECIAL PLACEMENT INITIATIVE — VW APPROVED — PERSONAL EFFECTS SECURED PENDING RETRIEVAL — DECEMBER 15, 1968. Ruth found her mother’s ledger entry—Grace Caldwell, admitted March 1968, pregnant, father unknown. Grace was gone on December 16th, but the doll in the hidden room held an ultrasound photo, yellowed, the blurry shape of a new life.

Earl had told her Annette Briggs would know more. Annette sat at Vernon Whitmore’s polished desk for forty years, a hand at the reception, eyes that had learned to hide memories behind scheduled appointments. When Ruth showed her the photographs on her phone, the dam broke. Tears, then silence, then the precise, haunted accounting of an adult who had been nineteen and helpless and then shackled by fear.

“I made those dolls,” Annette said, her voice small. “December 14th. We were playing Santa. He told us they were going to visit families for the holidays. The children were so excited. Tommy kept rubbing his medal on the chain like it was talisman. He wouldn’t let me put the doll on until he’d kissed it.”

“You were sent away that night,” Ruth said. “He told you your mother was sick.”

“He said she had a heart attack,” Annette said. “Said take the night. He said not to come back. He had Sheriff Pike there when I came back in the morning. ‘Emergency relocation for safety,’ he said. ‘Moved to other facilities.’”

Annette produced a small notebook, pages filled with notes she had kept at the edges of fear. She had watched Vernon shuffle documents, seen files moved to his home office. She knew—had memorized—the cadence of his life: the throwaway phone calls, the signatures, the dates. She had, over decades, quietly collected crumbs. There was a storage unit off Route 12, she said. A key at the bottom of her pocket. Unit 47.

Ruth brought what proof she could to the motel that night, photographs and ledger pages and the small ultrasound. Someone called with a Boston area code and the name Richard Morrison. He was in his late forties, with a careful posture and the kind of voice tempered by years of trying to belong to something that had always felt faint. He told her his adoptive father had used the word bought. He had found cash withdrawals, receipts, and then a receipt on Willowbrook letterhead—placement fee for one male child, age nine. The numbers matched the ledger.

Earl warned them all—Earl who remembered names—Vernon had the sheriff and the courthouse and the newspaper under his thumb. The idea of evidence felt fragile as a bird’s wing. But they found ways: filming Vernon’s hand at his safe, mapping the thumbprint patterns, copying six-digit codes from frantic frame-by-frame plays. They waited for the days when Vernon planned to be away.

They did it with the clumsy elegance of people who had nothing to lose. Ruth, Richard, and Annette moved like thieves with a purpose. They used gelatin casts and a small kit Ruth had bought from an earnest clerk. The safe opened; inside were names and destinations and prices. W1 through W43. Prices written like a butcher’s ledger. Names of families and institutions, payment schedules, notes about “special circumstances” and “research placements.” A rusted journal from Vernon himself prosaically described the operation: Final solution implemented. Sheriff Pike handled beautifully. Three trucks, two vans, five drivers. Children distributed across state lines within six hours. Total profit $445,000.

When they left the house, armfuls of paper and a journal that smelled like smoke and calculation, the night was a throttle and an ache. For a few hours it felt as if everything might be set right. Then the men in suits slowed the motel room door and Vernon Whitmore stood there, as sudden and inevitable and polite as a closing casket.

“Return what you took,” he said, with the soft voice of a man who had built a town. “Leave town and you will not lose your mother.”

Ruth thought only of one thing: the woman in Cedar Falls whose mail had been addressed by a trust called The Willowbrook Foundation and whose beneficiary number matched the ledger. W23. Her mother was alive, ten miles away, living under medical care that lived in Vernon’s maintenance of truths. For forty years Grace had been told her baby had died and that the memory of a child was only a delusion shaped by hormones and broken families.

Ruth and Richard drove to the Victorian in Cedar Falls at dawn. A nurse hesitated at the door, then let them through with a look that carried both guilt and a dull, professional compassion.

“She doesn’t get many visitors,” the nurse said. “She remembers different things on different days.”

They found Grace humming in a small room painted yellow, a faded robe draped over shoulders that had aged like a rope left in sun. The ultrasound photograph in Ruth’s hand slid across between them like a sheet of arresting truth. Grace took it and studied it as if the photograph was a relic from a past she didn’t trust.

“You have my mother’s eyes,” she said when she looked up, voice a scratch of child and old woman. “Green like spring grass. I named you Spring. That’s what I had planned.”

They wept then—the mother and daughter stitched together across a circle of fifty years. Grace’s memory was fogged by medication and by the cruel convenience of being easy to explain away. But the fog lifted like a tide. She remembered the trucks. She remembered the children’s hands at the dinner table on the night before they left. She remembered the dolls and the promise. She remembered the way Annette had laughed and the way Vernon had looked like a man with a ledger in his smile.

Vernon crumbled in time. The FBI had been watching too, following the trail that Ruth had left like breadcrumbs. Where they had been brave, others had been careful: an investigator in Boston with a burned out ambition, an ex-doctor from Marshfield with a folder of conscience, a ninety-one-year-old night nurse with a shoebox full of blurry pictures of children being loaded into trucks. Vernon’s world that had been built by hush money and clean checks came down with a racket and a flourish the likes of which had not been imagined by the men who had shared his dinner tables.

They broke into Vernon’s study in the way people do when there is no other way. The safe opened and the files spilled out like a confession: names, addresses, counts of money, notes on transfers, and worse—records that read like death certificates and clinical notations from Marshfield and Blackwood Research that almost made Ruth throw up. The journals described children as inventory; the receipts called them commodities. Some had been placed with families, some with institutes that conducted experiments.

When the FBI knocked Vernon’s arrogance from his cold, papered face, he pulled a pistol. It did not save him. The gun clattered and a hospital bed became his courtroom. He listened, incredulous, as a parade of witnesses he had paid, bullied, and betrayed took the stand. They were not the only ones who had the courage to speak: a former Marshfield physician produced records that read like medical horrors, the night nurse produced snapshots of children being loaded into trucks, Annette described, in a voice that shook with decades of suppression, the dolls she had made and the children’s small treasures placed inside.

Grace testified with the brittle authority of someone who had been stolen and then told she was mad for remembering. She told the jury what it was to have your personhood packaged and sold. “They told me my baby died,” she said plainly. “They gave me a death certificate. They gave me pills to make it easier to forget.”

The first verdict felt like a window opening to a sky none of them had expected to see. Guilty on counts that would have sounded like legend in the 1960s—human trafficking across state lines, falsification, conspiracy. Vernon’s sentence was measured in years, but those were years that would not bring back the children who had died, the lives that had been manipulated into other people’s stories.

Some families had indeed given what they thought were loving homes to children with a history they were never told. Several adoptive parents, when confronted with the truth, wanted to do the right thing. Others recoiled. The country listened for a while and then went on with other scandals. But in Milbrook the truth had a life of its own.

They exhumed the dolls properly, cataloged them like sacred objects, and returned them to the children who had survived or to the families who had buried them without a body. At the storage unit, Ruth found boxes of report cards and drawings and letters that had been kept like a secret shrine. At the bottom of one box she found admission papers that had been erased and rewritten until the trace of a life was gone. One sheet in Vernon’s hand read, in the neat cruelty of his chronicle: Final inventory complete. Buyers confirmed. By tomorrow night Willoughbrook will be empty. And I’ll be rich.

The press could not manage a more righteous outrage than that, but the outrage was not what mattered to Ruth as she stood in the evidence room and touched the smooth porcelain of a doll’s face. These were children’s treasures: a tiny locket, a pressed flower, a penny with a smudge of gum on it. These were the things they had trusted to adults they thought would bring them back.

There is a moment when the legal system and the human heart meet and feel awkwardly practical. The FBI seized Vernon’s assets and a fund was established. It would not buy back years, but it could help pay for therapy and for the steady practicalities that come after a life has been unmoored. The memorial garden replaced Willowbrook. Forty-three markers, each with a name carved, a face remembered. Some had flowers. Some sat waiting like open questions.

Not everyone was found. Twenty-one markers stood with no flowers. Nineteen lives were still missing. Some of those people were dead; some had lives with names that had nothing to do with the ledger. Some might not want to be found. The search would not end because such wounds do not heal quietly. There was no tidy ending.

The humane ending—if there can be such a thing for an atrocity—was not the prison sentence or the headlines; it was the care and the return of what little pieces of identity could be reunited. On the day the memorial opened, survivors came from across the country like a ragged procession: a man who found his St. Christopher medal set it on his stone and cried for the father who had loved him; a woman who remembered a Bible that smelled like lavender pressed it into a case and called it proof that she had been someone before adoption; an elderly man who had thought himself descended from nowhere found a sister and a family and cried with the awkward, grateful relief of someone who had been given a place.

Annette came last, uneasy and brave. She had shredded and hidden and kept and been held captive by a fear that took a lifetime to loosen. She walked the garden like a woman in penance, then handed Ruth a shoebox. Inside were items she had kept hidden in storage: a half heart locket, a child’s ribbon, a whistle. “I thought if I saved enough of them, maybe one day they’d come home,” she said, voice breaking.

Helen Garrett, the night nurse, came too with a battered photo album, its corners torn like soft teeth. She had kept a list—names and fragments of destinations—a pilgrimage of guilt. She did not ask for forgiveness; she sat on a bench and watched as survivors embraced each other and the missing names gained their faces in conversations that folded and refolded until something like community began to assemble.

Ruth walked among the markers, fingers grazing stone carved with Grace Caldwell. Beside it, a small laminated ultrasound photograph sat under glass like a sort of secular relic. Her mother was there too, living in an apartment with a care plan and a community center she liked and a routine that did not include Mister Whitmore. Grace’s eyes, green as Ruth’s, wandered across the garden like a woman who had been given a new map for a life she had thought had ended.

“It’s strange,” Grace said one evening as they sat on a bench and the sun fell like honey across the stones. “To have a grave when I’m not dead. It marks my resurrection, I suppose.”

“You’re the best resurrection I know,” Ruth said, and they laughed through the wetness of it.

For Ruth the work would never be finished. There were still searches to make, leads to follow, a list of names that felt like a ragged prayer. She wrote a book—no, she did not call it a book at first; she called it an accounting. She wrote the stories of the forty-three, each as separate as a person should be, and donated the profits to the survivor fund and to organizations fighting human trafficking. She wrote because telling the story made it harder to be erased again.

Sometimes the survivors were angry. Sometimes they were relieved. Sometimes they wanted to press charges against adoptive parents who had made lives with their stolen children; sometimes they wanted only to be left alone. Ruth learned to listen more than she spoke. She learned the care of small returns—an old whistle placed in the hand of a woman who had been a child again for a moment, a pocket watch that ticked to life and started a memory in motion.

Years passed. The memorial garden became a place kids visited for school trips. They were taught a hard lesson—the cost of seeing some people as disposable. Names were read by third graders who learned horror and compassion in equal measure. The empty stones remained; Ruth sometimes brought fresh flowers to those who were still missing, because grief deserved ritual even when there was no person to put the flowers into. The boxes of dolls had been distributed, some to living survivors, some to the relatives of the dead. Her own house held Grace’s doll in a small glass cabinet, the ultrasound laminated and framed beside it. Sometimes, late at night, Ruth would take the doll out and hold it, feeling the small weight inside like a heart.

Not everything closed. Several of the researchers who had taken children to test experimental drugs were dead, retired, or long gone. Some families who had bought children and found out what they’d done repented and cooperated. Some refused to accept what had happened. There was no universal truth. It was messy and human.

On the fifth anniversary of the trial, thirty-one markers bore flowers. The survivors and their families gathered for a quieter dedication. Grace spoke from a small podium with hands that trembled, and she did not talk about justice or revenge but about belonging.

“Forty-three children vanished on December 15th, 1968,” she said. “We found thirty-one. Twelve did not come home. Some of us were bought; some were experimented on. Some were given as gifts to strangers who thought they were rescuing. All of us were wronged. But we found one another. We told the truth. We named the missing. We built a garden where memory can live. We have done all we can, and as long as these stones stand, we will not let them be forgotten.”

There was no perfectly clean ending. There is rarely one when crimes involve numbers and the collusion of silence. But there was a community that refused to let the story fade. There was a fund that helped survivors with therapy and living expenses. There were laws reviewed in the light of vernacular greed. There were children who had grown and had children of their own who now knew where their roots tangled. There was cleaning, the slow, patient work of re-making lives.

Ruth kept writing. The ledger ended up in an archive, then a museum, then a book. She interviewed survivors in their own living rooms and in community centers and on radio programs that sometimes lasted only a week on the national stage. She had to be strong for those days, and she had to let herself fall apart in the small hours when grief returned like someone barging into a room.

Once, months after the trial, she drove back out to where Willowbrook had stood. The ground had been turned and leveled into a garden with stone markers and benches and a plaque that said simply: In memory of the forty-three. Children. Treasures reclaimed. Names restored. People lingered on the paths, and in the center a group of second-graders clustered around a teacher who read them the story of the dolls—carefully, with the adult edges shaved away but with the central truth there: someone had pretended the children were invisible and had been wrong.

A small boy in a blue jacket tugged on Ruth’s sleeve. “Did they ever find the rest?” he asked, the blunt, devastating curiosity of a child.

Ruth looked at the markers, at the faces of survivors surrounding the stones, at her mother sorting jam jars in a small volunteer kitchen at the memorial, smiling in a way that had only become possible after truth. “We’re still looking,” she said. “And we won’t stop.”

The boy nodded solemnly as if “we won’t stop” were a promise large enough to carry a whole world. Ruth thought of the dolls, the small treasures wrapped in tissue, the chains and the pocket watches and the pressed flowers. She thought of the way a garden can be planted where an orphanage once stood and how stones could hold stories like bells.

Her mother squeezed her hand and Ruth squeezed back. They stood together in a place that had been theft and had become a place of remembering. The world would keep being complicated and cruel in other places; the headlines would move on. But here, in this stretch of grass and stone and names, there was an honesty that would not let the forty-three vanish again.

At the edge of the garden, under a young maple tree, Ruth opened a small box and set down Grace’s doll and the ultrasound in a waterproof case and a tiny tin with a penny inside. She placed them on a marker that bore a name and an age like a small, necessary wound.

“It was all worth it,” Annette said softly, standing beside them, voice held high with the fierce relief of someone who had finally learned to say the truth. “They deserved to be remembered.”

Ruth watched the crowd: survivors and descendants and neighbors who had once walked past Willowbrook and turned their faces the other way; people who had stood and listened and learned. There would be more searching and more disappointments and more small triumphant returns. There would be some who never came home.

But the dolls had waited in a hidden room for forty years, patient and waiting the way memory waits, and someone had come back to open them. The treasures inside had been reclaimed by names that were not ledger entries but people. The story of Willowbrook would not be neat or cinematic. It would be long, slow, messy justice stitched with the fragile, stubborn thing that makes people keep looking for one another.

Ruth stood with her mother in the late light, and the air smelled of cut grass and the small, exacting peace of survivors telling their truth aloud. She had her mother’s hands now, a remake of the past, a hand that had once been sold and then repossessed by the truth. She had a daughter named for a child once lost and for a woman who had survived the ache.

A bird landed on one of the polished stones and hopped there, unafraid. Ruth watched it, and in that small, bright movement she felt the close-carved work of healing—not perfect, not whole, but moving forward. They had reclaimed names. They had told the world that the children had existed. They had shaped a place where people could say their names out loud.

She would never stop looking for the missing, not because a ledger demanded it nor because the headlines had faded, but because some promises are made not by men with ledgers but by mothers and daughters and the children who leave behind toys. Those promises could not be sold. They had been remembered by dolls, by a rusted ledger, and by people who chose the hard work of making the absent present again.

“Ready?” Grace asked, as they turned to walk back toward the visitors and the small, human chatter that made the memorial a living place.

Ruth slid an arm around her mother. “Ready,” she said. And for the first time in a very long time the word felt true.

News

“YOUR FIANCÉE WON’T LET YOUR DAUGHTER WALK.” The Boy’s Words Split the Garden in Two

The garden behind Ravencrest Manor was designed to look like peace. Every hedge cut into obedience. Every rose trained to…

“LOOK UNDER THE CAR!” A Homeless Girl Shouted… and the Millionaire Froze at What He Saw

The city loved routine. It loved predictable mornings where people streamed out of glass buildings holding coffee and deadlines, where…

End of content

No more pages to load