Halfway up, Leisel’s foot slipped. She grabbed at the clay and went down, her knees disappearing into brown. She tried to get up, fists sunk into sticky earth, and could not. Her breath was a short, pained thing. Around them, thinned people pressed forward. No one stopped. No one liked to be the one who held up a line, who attracted the soldiers’ eyes.

“Get up, Mama,” Anna begged. Her voice was a dry thing. “Please—”

Leisel planted the strap of the bag like a walking stick and pushed, but she could not rise. “Go on without me,” she said, brittle and strange. “You tell them my name. I will manage. I am fine.”

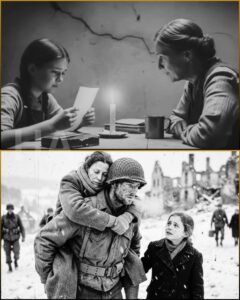

Anna wanted to scream, to drag her mother to her feet. Someone ahead shifted away, suddenly distant, their face like a small mask. Then a soldier passed them by—only one, walking alone with his rifle slung, helmet tilted slightly back. Mud spattered his trousers. He looked at Leisel and slowed. He did not do anything dramatic. He met their eyes with a puzzled, gentle look and said something in English that meant nothing to Anna’s ear and everything to the shape of his mouth.

Anna clutched at the habit of fear. The radio had taught a tidy hatred. Let the enemy touch you and you had betrayed something. To accept help was a betrayal. “No,” she said, hurried and hot with shame. “No, you can’t—”

The soldier crouched until he was the same height as Leisel. He pointed—first at her, then at his own back, then up the hill. The meaning was plain as any command. He lowered himself, offered his broad back without a word of ceremony. He did not push or order; he bent like a person making room.

Anna watched in a state that felt suspended between terror and astonishment. Leisel looked at her daughter, then at the soldier. It was almost indolence—an ordinary human decision, a woman saying, I will let this happen—and then Leisel lifted and folded herself onto the man’s back. He hooked his arms beneath her knees and rose, carrying her as though she were not a burden but something treasured.

Around them the crowd watched. A few faces hardened. Many softened. Someone began to whisper the only German she could hear now: “Danke.”

Anna had a question burning in her throat that was part defiance, part wonder. The radio had taught her a different truth. She could not swallow it. “Warum tragen Sie meine Mutter?” she cried, English and German braided into one, the words falling into the rain: “Why are you carrying my mother?”

The soldier turned his head, and their eyes met. There was no cruelty there. He smiled—small, nearly weary—and said something that sounded like “Okay” and then kept walking uphill, steady-footed, careful of the mud. At the top he knelt so Leisel could slide down without jarring. She touched the ground and stood, wobbling, and pressed the letter that had come the night before into Anna’s hand. “Danka,” she said, the word fumbling itself out.

The Americans took names inside the half-roofed school, checked lungs and eyes, weighed people and wrote things on forms. The doctor made small marks: underweight. Red marks. That mark turned into extra stew. The ration card had been given life.

In the weeks that followed, the trucks returned with the steady, repetitive kindness of logistics. They brought more food, clothing, sometimes toys for the children. The town began to re-weave itself with these long, olive-green threads of supply. But the Americans did more than feed: they showed films in the hall—newsreel films with a German voiceover—a terrible, clarifying thing.

Anna sat with her mother and the old neighbor Frau Becka in that hall. The room smelled of wet coats and fear. On the white sheet they played images of fenced rows, of striped uniforms, of faces like something stripped of flesh by hunger and despair. The projectionist clicked and clicked, and the German voice read numbers: six million. It was a word that had been a whisper, now poured into light and into their eyes.

The film did not sit easily with the soldier’s small kindness on the hill. For Anna, that simple kindness and the images of the camps combined into a force that pulled at something deeper: if men in uniform could tenderly carry a woman and also be shown how monstrous human beings could be, then what did that mean for what they had believed? Where were the lines between victim and perpetrator? Between human and monster?

The town held meetings—hearings, they called them—and the Americans required the residents to answer questions on long forms. Who were you? Were you a party member? Did you support the SS? Men who had sewn their small party badges into coat linings were asked to show their hands. Some declared that they had not known. Many said they had only followed orders. A few, when films and testimonies made it impossible to remain comfortable in ignorance, wept.

Anna kept her father’s last postcard folded in her jacket. The last line of it—Do not worry. We are being moved to the rear for rest—was like a ghost whisper: not gone, not yet. Weeks later a letter came from Carl, and the handwriting that had once been so familiar bent the paper into a map of another life. He wrote from Texas, from a camp, from a place where he had been given bread and orange rations and where he and other prisoners were being treated under what he called, slowly and with a kind of astonished gratitude, “the Geneva rules.” He described oranges, baseball games, baths, clean clothes.

When Leisel read the letter aloud, Anna had to sit down. Carl was alive, his words were a thin bright thread connecting the cellar to someplace else, and there was something almost obscene about the contrast: here, people with less than a thousand calories a day; there, prisoners fattened by the victors’ rations.

“It is wrong,” Leisel said, clutching the paper. “They bombed our bridges. They shelled our fields.” She looked at Anna as if she expected support for the old fury. “And yet,” she went on, voice cracking, “they feed our men in their camps because of a rule. They obey a paper.”

Anna’s question about the soldier’s small courtesy widened. The same uniform that had brought bombing also kept a book of rules that restrained cruelty in some places. The same men who had leveled buildings had men among them who followed a code.

Then the worst truths arrived like a winter wind. An officer walked through the emptied rooms and asked people to come to the hall. Behind a curtain they set up a projector and showed films of camps—bodies, piles of clothing, faces that could not be ignored. Some people had already whispered about places like Auschwitz; others shouted, “Lügen!”—lies—but watching the images put the whispers inescapably in front of them. The town’s pastor stood up afterward, the same man who had once asked God for victory, and he asked instead for forgiveness. “We were blind,” he said loudly, “or we looked away.”

Arguments broke out on the muddy square. Some blamed Allied bombing. Some wanted to believe they had been kept ignorant. Others, older or sharper-eyed, said that the signs had been there—the sacked shops, the missing neighbors—and they had approved in the silence, or cheered the trains that carried away the ones they were told were enemies.

Those meetings were the story’s real turning point. The hill that had once been simply a way to the school became the place where the town learned to look at itself. Anna watched faces contort; she heard men who had once worn proud uniforms say, “We didn’t know,” and she saw the people who had been called “followers” shiver as their own part in a crime became visible. The simple kindness of the soldier did not make the film less terrible. It complicated the town’s image of itself.

In the following months, the town started to rebuild with tools both literal and philosophical. New books arrived for the school—pages about human rights replacing the old pseudo-science—and American officers came to talk about elections, about rights and responsibilities. The Americans who remained were not monolithic. Some were brusque, some were tender, and many of them were young men who had been pulled from farms and towns in the United States and found themselves students of a world far more complicated than training manuals had prepared them for.

The Marshall Plan’s aid came later like a new current. Trains that had once carried shells now carried coal and steel. Machines rumbled back to life, and the first hum of factory belts in months felt like a slow resurrection. People who had been too hungry to pick peas learned to turn their hands to bigger things again. Leisel’s cheeks filled out slowly; her hands did not show the blue veins the way they had. The yard in front of the school was paved, and children played on it without fear of splinters.

Carl returned in early 1947 with a gray, uncertain smile and a suitcase that smelled of ship oil and laundry. He was healthier than many of the men who had never left, a bitter irony that did not escape the town. He hugged Anna until she felt the strength in his arms, as if making up for two years’ absence. He talked of Texas and of the odd tenderness of captivity under a rule: “A guard gave me bread because he was told by the book,” he said, both exasperated and grateful. “How do you keep your hate when someone offers you rules and not revenge?”

Years passed. Anna grew into a woman with her own small stubbornness. She married, had children, and in time returned to teach in the same school on the hill. On the classroom wall, maps did the work that portraits once had. She taught the kids how to read timelines: the camps, the trials in Nuremberg, the rebuilding. She taught them to ask hard questions. But she always saved a day each year to tell them a small human story.

She told them about rain on the hill in 1945 and about the soldier who bent down and offered his back. She told them about her mother and the single, trembling English word she could manage: “Danka.” She told them about the film in the hall and about the moment when a town learned to look at itself. Students would frown and ask why the soldier had carried her. “Because someone chose something small to be humane,” Anna would answer, and the room would get quiet.

Time did a curious thing: it made enemies into acquaintances and acquaintances into partners. The world’s political maps shifted. West Germany and the United States would stand on the same side of a new map called the Cold War; farmers in her town would sell cars to Americans; students would go back and forth between the Rhine and the faraway states. Anna taught her children both the ugly truths and the small acts of courage. “Remember,” she would say, “that choices matter. Propaganda can shout, but real kindness does not need a loudspeaker. It just bends down, lifts, and walks.”

When the film footage of the camps had first been shown, some in town had denied or delayed their grief. They had blamed the Allies; they had pointed to Dresden’s ashes as proof that wars make monsters on all sides. But after the trials and the evidence—after the days when neighbors who once congratulated themselves on “cleansing” their streets now stood with bowed heads—two things remained. One was the historical fact: the regime had built and run places of industrial murder. The other was the human fact: people could change, and perhaps must. That knowledge settled over the town like a new layer in the soil.

Decades later, Anna would meet an American veteran at a local gathering that brought together former civilians and the soldiers who had once stood above their town. He had an easy, loped walk and called himself Jack. His German was stilted but sincere. He said, in a voice howled by memory, “We came thinking we knew everything. We left understanding that power was not wisdom.”

Jack told the room how, in his training, they had imagined the enemy as nameless and dangerous. Then he showed them the camps and the ruins and came home with the knowledge that the capacity for cruelty existed everywhere. “We learned the same lesson,” he said. “That being strong does not make you good. We had to choose how to be human when we had the chance.”

They talked into the evening. The old edges smoothed in that conversation because both sides had learned. Carl came to that meeting, too, and the two men shook hands like they had known each other forever. They spoke about baseball and about bunks in Texas, and Jack asked with a soft curiosity whether Carl still remembered the smell of oranges. The exchange was simple, human and strange, nothing like the rhetorical thunder of the radio.

In the classroom on a crisp morning, Anna would press her palm against the map and say, “History is not a list of winners and losers. It is a place where we must ask how we lived. Did we stand up? Did we look away? Did we carry each other when we could?”

Her students, some of them the children of men who had once sung nationalist songs, would sometimes look at the small black-and-white photograph she kept in a drawer: a soldier with his back bent and a woman on his shoulders, mud clinging at his boots. It was not a picture that could answer all questions. It was a picture that asked one simple thing: what will you do?

The climax of the town’s moral reckoning came not in a single trial or speech but in a small, painful process: people listened, they testified, they named names. The American film had cracked the radio’s loud lie, but the important work was what happened after the screen went dark. The pastor’s confession, the farmer who admitted he had cheered the deportations, the neighbor who finally took down the torn poster—these acts were the slow, human stitches on a torn fabric.

Later still, when Anna was old, she would walk to the school yard and sit on a bench. Children would run past, their laughter like water. Someone who had been a child in 1945 would come by with grandchildren and say a word about the time the Americans came. Old men and women would tip their heads at each other, sometimes in forgiveness, sometimes in memory. The hill was paved now; the mud was a memory. But the memory that mattered most to Anna was the small, defiant kindness of a man who had been trained to win a war and who, in the middle of mud and rumor, chose to carry a woman.

She never learned his full name. Soldiers moved on, decay and politics shuffled positions. But she sometimes imagined what he had seen—the ruins, the hunger, the camps—and how he must have felt when the projections in the town hall had shown the death of so many. Maybe he had been changed by it, maybe he had carried that weight like a secret, maybe that was why he had knelt down and offered his back.

On the last day Carl came back to the river with Anna and watched the barges go by. He held her hand tight and said, “We were broken in many ways. But look how the river moves. It takes things and brings things. It is not a simple story.” He smiled, sad and affectionate. “We will teach them not to be blind.”

Anna lived long enough to see the town change in ways she had not dared to imagine on that muddy hill. Windows were whole. Children had more than scraps. The radio’s old wooden cabinet had become a relic on a shelf. But she never let the story of the hill become a parable without its teeth. She told it with all its contradictions: the bombs, the kindness, the film of the camps, the trials and the slow work of living well after the worst things had been done.

Once, when a class asked if there was forgiveness for everyone, she said, “Forgiveness is not forgetting. It’s choosing differently after seeing the truth. Some will never change. Some will. We must make our choice and then teach the next ones to choose the right small things each morning.”

Years later, at a memorial for the dead, Anna stood with a sprig of flowers in her hands. Among the gathered crowd were former soldiers and civilians, and somewhere not far, a man with a face lined by sun and memory rested his hand on the top of a headstone. Jack had come back, older, his hair silver. They saw each other across the stone and walked together. There was no grand reconciliation, no proclamation that all was healed. There was simply two people who had once stood on opposite sides of a history, and now they stood side by side, looking at the same stone.

On the hill where Anna had once watched the soldier bend, now children built a small fort of branches and laughed. A breeze lifted the hem of a scarf and carried the faint smell of bread from a nearby bakery—real bread, brown and rich, not the rationed loaves they had once known. It was ordinary and miraculous all at once.

Anna thought about that rainy morning often. About the shock of the soldier’s small smile. About her own question, hurled into the rain: Why are you carrying my mother? She had asked it with anger and fear and an ache that surprised her by how grateful it was. The answer had been given without words: a man who did a simple human thing.

She taught that answer to her students not as a tidy moral but as a task: when you can, carry. When you are the stronger, bend down. When the world insists on loud lies, choose to do the quiet correct thing. The radio had been loud for years; the soldier’s back was quiet.

Towards the end of her life, Anna would sit by the window and watch young parents push prams along a new, smooth pavement. Once, a little boy trotted up to her with a chocolate wrapper he had found in the gutter and offered it like a peace offering. Anna took it gently, smiled, and thanked him. It was a small absurd thing, but it felt like the same miracle carried forward: the giving of something unexpected, unlooked for, without announcement.

In the end, the story of the hill was not only about an enemy who lifted a woman. It was about a town that learned to look, about a people who were taught by pictures and by rules, and about a child who had the courage to ask the question that cracked a lie. It was about choices—small, human, stubborn choices—that, when added together, turned a ruined place into a place where people could learn to be better.

Anna died old, having told the hill’s story a thousand times. At her funeral the town gathered on the paved slope of the school. People placed flowers on the grave. Among them stood a man from across the sea—weathered, gray-haired, eyes soft—and he spoke quietly to those who would listen.

“He carried a woman up a hill in the rain,” he said. “It didn’t fix the world. It only changed one moment. But that moment made a child ask why, and that child taught others. Small things matter.”

And the crowd—old neighbors, former soldiers, children who had grown and had children of their own—walked down the hill to the square and, for a moment, lived in a world where the choice to bend and lift was more important than any voice shouting what was or was not a monster. The heavy radio had been put away. The world was messy and frightened, still capable of darkness. But in that town by the Rhine, people remembered the soldier who knelt and the girl who asked, and they tried, as best as they could, to carry others when they were able.

News

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

The Black Girl So Brilliant Even Science Could Not Explain Her

Only the long corridor, fluorescent and indifferent. Now it was the third night, and James couldn’t breathe inside his own…

The Plantation Master Who Left His Fortune to a Slave… and His Wife with Nothing

At first Ethan’s mind rejected it the way the body rejects a bad transplant. It didn’t fit. It wasn’t allowed….

The Laundress Slave Who Dr0wn3d the Master’s Ch!ldren on Easter Sunday — A Cleansing of Sins.

Everett’s first reaction was fury, hot and immediate, the way a wound reacts to salt. Not at the child, exactly….

The Vengeful Cook of Charleston: Slave Who Poisoned Her Master and His Guests at the Christmas Ball

Elliot’s hands shook. He reached into his pocket, pulled out his phone, and fumbled the screen like it was suddenly…

The Voodoo Priestess of Louisiana: The Slave Who Cursed Her Master’s Family to Madness and Ruin

The boy nodded too fast. “I know. I’m just… I’m just waiting on my mom. She works over there.” He…

End of content

No more pages to load