Thomas Weatherbe was twenty-one and his boots still remembered the soil of Nebraska. He had grown up knowing precisely how to read the color of a field, how to find the good ground under bad weather. Those practical lessons became habit inside him: be steady, do the right thing, plant another row. War had taught him other things—how to move low through grass, the sound of a mortar, the way comrades could be a kind of family—but in his chest was still the small, stubborn warmth of someone raised on community and plain speech.

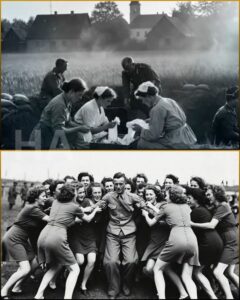

On April 19, 1945, his company was ordered to clear Waldenbach. Intelligence suggested pockets of resistance. For weeks there had been little but surrenders. Thomas expected the same. His sergeant, George Hawley, was a veteran with a throat like sand from too much shouting. The assault began the way assaults often did: with rifles high and coordination thin. Then they heard the odd pattern—the shooting was sporadic and hitting little. Thomas, who had a way of noticing the human rhythm behind noise, saw that something in the German positions was wrong.

He and three others flanked around the ridge to the north, creeping through stubble and hedgerow until they could see the line below. He stopped, and for a moment simply stared. It took a breath for comprehension to gather around his chest.

“They aren’t soldiers,” he said in a whisper to Private Ruiz, who was pressed close beside him. “Look.”

Below, in the embrasures and behind stone walls, were women. Not a handful of them but rows—dozens—heads leaning forward, rifles held awkwardly, some with scarves still tied in a way that said nurse, not combatant. Greta saw the American silhouettes on the ridge and for a moment her mouth went dry in a way that had nothing to do with thirst. They had been set like stakes into the ground.

“Command says the position must be taken,” Sergeant Hawley said into the field receiver when Thomas called in his observation. His voice assumed the routine hardness of orders. “If they’re using non-combatants, we still take it. We’re not here to debate their command structure.”

Thomas thought of the bandages he had seen, of men who had once been boys he’d shared beans with. He thought of his father’s hands. He made a decision that felt like turning a wheel sideways so a cart might not break.

“Sir,” Thomas said into the mouthpiece, “we’ve got a surrender—non-combatants. I can move down; we don’t have to shoot.” The tone on the other end held for a long time before the reply came: “Are you certain?” “Yes, sir. If we assault it will be a massacre; they’re not trained. I can take it without firing a shot.” There was another pause, and then, unbelievably, the commander’s voice softened the edges of orders. “Avoid unnecessary casualties. Take the position.”

Thomas felt his throat go dry and then emptied his rifle and, as if that were a treaty, set it down in the dirt. The rest of his squad followed like a small, slow procession—rifles lowered, hands open.

When they walked down the slope, the women shrank back and for a moment a thin wind of old fear passed between them. Greta clutched her Mauser with trembling fingers because she had been taught to keep it. She had been told what would happen in captivity by the men who believed the lies: capture meant shame, brutality, worse. The rumor was a noose. Yet here was a lanky American in a face full of open, bewildered honesty; he looked like a boy come from fields and had the peculiar air of someone who would rather scold a mule than a woman.

He called in German with the few words his immigrant grandmother had taught him: “Nicht schießen! Nicht schießen! Wir sind hier, um zu helfen!” Don’t shoot! We are here to help!

Greta stared, the syllables landing like cold water. Her voice, when she found it, sounded small. “Wirst du uns töten?” Will you kill us?

“No,” Thomas said, as simple as a weather prediction. “No. We’ll let you live.”

She stepped forward. Her lungs wanted to convulse with relief and terror both. She walked unarmed toward the Americans like someone pulling a chair from a burning house. Thomas dropped his rifle and lifted both hands in a gesture that felt like prayer and surrender at once. The others did the same.

One by one, the women came down. At first they moved like leaves reluctantly detached; then they loosened. They sobbed and laughed in a mixture that made the ground seem to hold both seasons. By dusk, 128 women had laid their rifles down. Not a shot was fired. In the official reports later, the phrase used would be: “secured the surrender of 128 enemy personnel without casualties.” But that phrasing was brittle. It did not hold the wetness of hands shaking, the smell of starched uniforms, the small speech of a woman who tucked a photograph into Thomas’s palm.

Greta handed him the picture—a father and a girl in a garden. She folded the paper on the crease of a refusal to trust. “You saved us,” she said, in German that tasted like a benediction on her tongue. “You saved all of us.”

Thomas shrugged as if it were the same as propping a fence. “We did what we had to.” But the look in his eye was quieter; more than a shrug, it was the recognition that a line had been crossed from killing to offering life. That night, they were ferried to a processing center where officers argued in the rooms behind the lines about what to do with the female prisoners. The camp would be a temporary shelter before shipping. For those women, it was the end of an acute prayer.

In the days that followed, word moved like rumor. Soldiers wrote home to sisters who told cousins about a farm boy who had saved one hundred and twenty-eight lives by not firing. Journalists sniffed it out like hawks. Some officers were amused, others annoyed by the bureaucracy of gratitude. But the women themselves—those who had been given time and water—did something that would be puzzling and oddly beautiful to people who had not been standing on the brink of annihilation.

They petitioned.

It started as a letter—a chaotic thing written in careful, shaking English because they had been told that English might reach the men who had saved them. They called him by his name—Thomas Weatherbe—because names are a way to make a person solid. They told about the field, about rifles set up like doors to be closed on them, about the cold and the way Major Hoffman’s voice had said “no surrender” like a verdict. And at the end of the petition, written in a hand that made the phrase surge with earnestness, was one line that would travel a continent: “If possible, we would be honored to marry him—every one of us—if such a thing could be.”

The petition reached General Benjamin Hutchkins, a square-jawed man who had seen too many cemeteries to let his heart harden into stone. He read it twice and then smiled like a man who had watched a child make an offering. He ordered a small ceremony: one afternoon in June, in a field, with a flag and a makeshift stage. He wanted the women to be able to say thank you in person.

On June 15th, under a sky that had the crispness of late spring, the women formed up in lines. They had been given clean uniforms—prison camp attire that somehow turned into a costume of dignity under the sun. Thomas arrived in his utility shirt, his hair matted from travel, his face still sunburned from Nebraska. He had not expected this part: the weight of so many eyes on him, the chant that rose like a tide when he stepped forward.

“Danke, danke, danke,” they said together. Fifty voices and then one hundred and twenty-eight rose and became a single, rolling thank you. The sound pressed on Thomas like wind on wheat. He wanted to laugh and to cry and to hide. One by one the women came forward to shake his hand; some wept, some told him their names. The air moved with the small miracle of people whose lives had been returned to them.

A document was produced and each woman signed it in careful English. The document read not as satire but as a testament. It said, in part: “We the undersigned women of Germany…hereby testify to the courage and compassion of Private Thomas Weatherbe…He made the choice to see us not as enemies but as human beings…We will carry his memory with us for the rest of our days…and we declare that if we ever have the opportunity, we would be honored to marry him, all of us together, if such a thing were possible.”

No one expected Thomas to take the phrase literally. No one in that field thought that a man could or should marry a hundred-and-twenty-eight women. People love hyperbole when their hearts are full. What stunned everyone was the depth of affection attached to that hyperbole. It was not about sex or possession. It was about gratitude that wanted to translate into something permanent. They wanted to give him their forever as men give a life’s worth of thanks. For them, it was a vow that said, “You have saved our beginnings.” It was their way of binding the gift of existence to his name.

The story travelled. Newspapers printed photographs of the gathering with captions that tried to be concise and proper. “Farm boy hailed as savior,” one headline read. People liked a story in which one person’s decency could stand against a machinery of cruelty. Thomas was offered promotions and interviews. He accepted neither; he accepted instead something that felt truer: letters.

They arrived from odd places—Germany, the camp, families, other survivors. They were full of small detail: a child born in a town that had been shelled into a shell of echo who now had a name because his mother had lived; an aunt who had been found behind a hedgerow and had hands to make bread. Greta wrote in German and English sometimes in the same note. She told him of a daughter named Sophia, of a man she married who returned from service and hammered out a life from ruins. “Mama,” Sophia once asked, according to Greta, “did you marry him?” Greta wrote that to a child, marriage meant homes and names and the way hands fold in sleep; no, she hadn’t, she wrote, but in a more important way they had. “We married him by keeping his memory in our lives,” she wrote.

Time amnioted the life of that field into different seasons. Thomas returned to Nebraska. He married Catherine, who folded quilts and had a laugh that smelled of biscuits. They planted cornstalks and had four children. He told his family too little—he had been raised not to grandstand. When he spoke of the war, his mother would press his hand as if checking a fever. The men in his town called him a hero sometimes and he deflected it with a farmer’s humor. “I just did what made sense,” he would say, and someone would nod as if he had said a weather proverb.

But the story was not simply literary. In 1946 the American Legion organized a reunion in Munich. Thomas was asked to go. He was uneasy. What use was one afternoon of being thanked? His mother told him to go because she believed gratitude ought to be seen and that he had a duty to be present for the people he had saved. He flew across the ocean and found himself met not by the press alone but by faces—faces he remembered like stained glass. Greta and others hugged him, their hair threaded with gray now, their smiles soft from having survived an additional season. More women came to the reunion than had originally been in Waldenbach because the story had become a myth people wanted to bless. It was a strange festival of survival.

In Munich, he gave a speech. He spoke plainly: “I was taught to be a man in Nebraska,” he said. “My father said your word is a thing you plant. I learned that day that sometimes the bravest thing you do is not to shoot. Sometimes the bravest thing is to stop and say: you are a person.” Tears slid down faces in the crowd—men and women both. When his voice broke his words went to the place in hearts where gratitude rests.

Years passed. Letters came and went like a slow train. Eventually Thomas died in 1992 at sixty-eight. He lay in a small hospital bed on the farm, windows curtained against the autumn wind. Catherine held his hand; their children folded themselves like bees into the quiet. After his funeral, those who had survived Waldenbach gathered again—older, their hair white, their footsteps deliberate—and in the field where they had stood decades before they spoke of mercy like a prayer. They told stories of men and children and of the small ordinary events of life that in their telling had the weight of epics: a granddaughter’s first day of school, a garden where cabbages grew, a neighbor’s laughter after the power came on.

Anna, who had been the youngest among the women, stood and spoke during the memorial. “He could have killed us,” she said, voice like a reed. “He could have done what soldiers do. But he didn’t. He saw us. He saw us as mothers, as daughters, as women with future days. He made a choice. That choice was a life.” People who had children of their own listened as if to a history that was also a sermon.

The marriage petition lived on not as a literal plan but as a symbol. The phrase “We will all marry you,” when told in different languages, took on some of the qualities of a promise and some of the magic of a folk tale. It was not a possessive claim. The women who signed it were not asking for Thomas’s body; they were asking to tie gratitude to a human life so that the memory of mercy would not dissolve. They wanted to name the man who had taught them that even in the machine of war there could be personhood.

As the years wore on, younger generations would ask about the story. “Did you really marry him?” Sophia once asked Greta. “No,” Greta would answer, her hands busy at the knitting that had kept her steady during nights of worry. “But in the way that matters, we did. We married his example into our lives. Each time we choose to be kind—we think of Thomas.”

History is a censor of small stories; it chooses what to remember. The marriage petition faded from front pages as Cold War tensions grew and the world folded its anger into new shapes. Yet among the women and their descendants, the story was given new life during births and funerals and when a child needed an example. It became less about a single man than about the idea that a soldier’s act could be an act of preservation rather than annihilation.

When a documentary filmmaker named Klaus Hoffman tracked down some of the surviving women and Thomas—then in his sixties and still the same quiet man—a film was made called We All Marry You. In it, Thomas said things he had rarely said aloud. He told the camera, “If a life is a field, then planting kindness is how you make sure the future’s food is good. I didn’t feel like a hero. I felt like someone who refused to be numbed by orders.”

Anna, older and small, looked into the lens and said: “He saved my life. He saved our lives. We married him in the only way we could: with a promise that we would live in the way he taught us to live.” The film did not make them famous forever; it made them humaner, a slight correction to the ledger of history that often counts only victory and loss.

Greta’s daughter, Sophia, grew up listening to her mother weave the Waldenbach story into the family lore. “Mama,” Sophia asked one day when she was old enough to know the edge of things, “did you ever feel angry at what we were made to do?” Greta looked at her daughter, at the hands that had wound egg strings into a loaf, and she answered softly: “Of course. But anger is like a fire; it can warm or burn. We chose to use what we learned to build, not to destroy. Thomas’s choice made that clearer.”

Once, late in life, in a church yard near Waldenbach, a small girl traced the letters on a plaque that had been installed by descendants. The plaque read—simple and unadorned—that on an April day in 1945 a choice had been made that saved 128 lives. The child did not know what the war had meant in policy or doctrine, but when her grandmother told her the story, she learned the smallest lesson first: a person with a kind hand can change the path of many lives.

Thomas’s children grew up with a quiet, sometimes bewildering legend. Their father was a man who tilled the land and sometimes hummed a German tune at night. They never felt the full weight of the petition, only its echo. They learned to love the modesty of him—how he would give his neighbors milk in the morning without being asked. To them, the story was a prism: you could see heroism, mercy, and stubborn decency in its angles.

In the end, perhaps the most human thing about the marriage petition was that it forced everyone to ask: what does it mean to owe someone a life? Is gratitude convertible to anything material? The women of Waldenbach answered with a gesture that was both grand and simple: they took the feeling of having been spared and transformed it into living—into grandchildren and gardens and laughter. That, they believed, was the truest marriage one could offer a man whose brief and brave decision had been an inflection point in their lives.

The last reunion they held in Waldenbach was small. Autumn had raked the cornfields behind them and a late wind moved the grasses like a congregation praying. They stood together once more where the surrender had been held and remembered the way fear had turned into something else. Greta, older and shorter, took out the same photograph she had given to Thomas decades before and traced the face of the child in it. “He made space for us,” she said. “Not just in body, but in possibility.”

“Wir haben ihn geheiratet,” Anna said quietly—“We married him.” The phrase was no longer literal and it did not need to be. It was a promise and a lesson and a story told beside a woodpile to children. It was a way to say that one person’s choice to see another’s humanity is a kind of marriage to kindness itself.

Thomas died and the world turned around him. But his choice—simple, stubborn, ordinary as planting a row in good soil—continued to yield days: children who grew into citizens, women who became nurses and bakers and teachers, a village that rebuilt its roofs. If history catalogs winners and losers in columns, the quiet ledger that mattered kept a running total of spared lives. The women had given him a petition; in return he had given them continued mornings.

Years later, when a granddaughter asked what had compelled him to go down that field with an empty rifle, the answer was the same one he had given since the first moment: “My father said, do the right thing. I guess I just remembered that.” He had not been ordained by any flag or medal to make mercy. He had been a farm boy who chose another kind of courage—the courage not to add to the counting of dead.

And so the story moved along the lineages of memory—through Sophia’s child, through Thomas’s great-grandchildren, through the small town newspapers that printed the story on anniversaries, through the documentary reels kept in boxes. It was not a story to settle debates; it was a story to teach the simplest thing: when you have the power to end a life, you also have the power to preserve the many lives that might follow. Mercy, the women said with their petition and with their living, is not soft. It is the harding of a heart so it can hold more than itself.

The last scene belongs not to a field or a speech but to a kitchen table in Nebraska where an old man—Thomas’s son—sits with a photograph, and his fingers trace the signature of a woman named Greta Steiner. On the back, in a hand he never met, is a sentence in German: Wir haben dich in unser Leben aufgenommen. We have taken you into our life. He presses the photograph to his chest and smiles in a way that knows the exact weight of small, stubborn acts. He remembers the story his father told him—about a choice made in a valley at the end of a war—and in that memory he recognizes a truth: the world is made by people who do the right thing, even when it is easier not to.

That, in the end, was the marriage: not a contract signed on paper, but the binding of lives to a single act of mercy. And because it was real and because it reverberated through children and grandchildren, the women’s strange petition became not a comic footnote but a promise. They all—one hundred and twenty-eight voices—had indeed married him. They married the idea that life can be chosen over death. They married the hope that mercy matters. And in that marriage, both giver and recipient were changed forever.

News

STEPHEN COLBERT NAMES 25 HOLLYWOOD FIGURES IN A ‘SPECIAL INDICTMENT REPORT’ — A WEEKEND BOMB THAT SHOOK AMERICA.”

The 14-Minute Broadcast That Exploded Across the Nation It was supposed to be an ordinary weekend.A quiet Saturday night, a…

On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does not simply revisit the story of Virginia Giuffre. It tears apart the entire network of power that once fought to erase that truth from history.

“On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does…

THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE OF VIRGINIA GIUFFRE

“THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE…

They tried to bury her. She left a bomb behind.o press tour. No staged interviews. Just 400 sealed pages… and the names no one else dared to print. Virginia Giuffre — the survivor, the fighter, the woman whose truth once disrupted palaces, gyms, and studios.

Now, even after her death, Virginia Giuffre’s 400-page memoir is set to reveal the hidden battles, the names, and the…

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed before the world finally uncovered the truth..

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed…

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway I was paying for.

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway…

End of content

No more pages to load