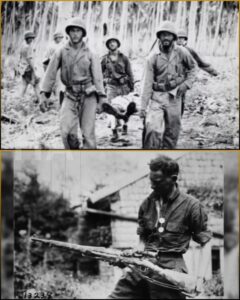

It did not matter. The battalion lost men. The snipers took them in the mornings, when men bent to fill canteens at creeks, when patrols threaded between trees on routes they had walked twice before and a bullet answered their footsteps with lethality. In seventy-two hours, fourteen men—friends, comrades, whole people—were gone. Captain Morris, who had the look of a man used to giving orders that altered maps, summoned John. He wanted to know if the rifle could hit where others could not. He wanted a man who could shoot.

“You’t from Illinois?” Morris asked, the letter of that question made small by the jungle steam. He had eyes set in a man’s face who had watched the sea’s curve and found death waiting on shore. “You sure you’re not just a paper marksman?”

John told him about Camp Perry, about six-inch groups at six hundred yards with iron sights. He told him about being the youngest to win. He did not tell Morris that the Winchester had been his pride for years or that he had packed mountain of advice into the little wooden box to reach him like a talisman.

“All right,” Morris said, finally. “You’ve got until dawn. If those snipers are still out there, and you can find them, do it. But do it with support. We don’t need a show.”

He carried the Winchester anyway. He kept it in the rubble of a bunker three days after they took a stretch west of Point Cruz. The place smelled of old smoke and the idea of abandonment. It was a hideous theater of branches and light and spaces where a man could vanish like a promise. He settled, alone because he had asked for it that way, and glassed the trees.

A branch twitched at nine seventeen. It was a small movement—nothing if you had never been taught to find death in the twitch of leaves—but John had been taught to watch the trivial, to make the trivial amount to something true. He steadied his breath, rewarded the muscles with the knowledge of repetition. The trigger broke like a thought. The first Japanese sniper went down in a fall that seemed both sudden and inevitable. John reloaded. He counted the breath between the thunder of the shot and the silence after.

He had thought of the rifle as a kind of personal, private thing. It turned out that in the heat of January, under the watch of banyans, it was a small machine of decision. It was also the beginning of a language he had never been taught—how to kill and not let killing dissolve everything you once understood as yourself.

He had killed five by noon. The men who had joked about the mail-order rifle stopped laughing and watched with a hunger that was ugly and quick to form. John would not allow an audience. Once, when he felt the edge of vanity call, he refused a cluster of onlookers and felt them scrape away like paper. Spectators were a risk; attention suggested that someone else was watching too, someone who would answer with the collateral and accept the cost of reprisals.

The Japanese adapted. They stopped moving in daylight, and John spent the afternoon looking through glass to find nothing but the canopy’s quiet. He learned to wait longer than he thought possible, to watch the make of shadow. The second day, rain came in sheets that washed the earth and made the trees look like they were weeping. The snipers used the weather as a cloak. The rain quieted the gross sounds of human movement and left only the taste of rain and the patience of men who had been taught long to be patient.

He found them again: at nine twelve, at eleven twenty-one, at two in the afternoon, always the same choreography—patience, then a hairline movement, and a decision. When a Japanese bullet cracked a sandbag six inches from his head at eleven twenty-one one morning, dirt sprayed his face, the nearness of death shameful and sharp. He rolled and pressed into a wall of sod and waited three minutes before he moved. It was rule—do not give the enemy the gift of a hasty action. He learned that you could not un-learn that.

By the third day the pattern had become a duet of hunter and hunted. John, in his bunker, and the enemy camouflaged in the trees, made a liturgy of sight and shadow. At dawn on the twenty-fourth, he found a decoy in a palm and the real shooter in a banyan as clever as the roots that held it. He used the bait against them—the decoy fell, and then the real man moved to the sound and John’s bolt tore another breath away. He had two kills in eighty seconds, and that, more than anything, was what forced the battlefield to change.

When mortars triangulated his previous position by muzzle flash and hail struck the bunker he’d sat in moments before, John ran. He sprinted and dove into a shell crater and felt the bunker vanish in fury and smoke. His rifle came with him. It was heavier wet, a weight tethered to a man who had no license to grow sentimental. He found a fallen tree, moved, set up again. The enemy was now hunting him. The difference between shooting snipers that were hidden and snipers who now sought him was two words: they would not hide their intent. They were no longer passive; they were active; they were teeth.

By the fourth day John had killed eleven snipers. He had fired twelve rounds at those hidden men; eleven had been true. The irony of a bolt-action five-round Winchester outperforming an army’s mass-issued weapons was not lost on anyone—even the armorer who had asked if the rifle was meant for deer or Germans. Men who had mocked him came and asked to watch, and John refused because the audience always cost someone a life.

There was a moment after the eleventh kill when John, exhausted, wrapped his hands around the rifle and felt a heaviness that had nothing to do with the wood or the steel. The grove, which had shifted subtly from a place of shadow into a place of bodies, gave back a sound he did not want to keep. Voices—Japanese voices. Footsteps. A patrol. They were coming to collect the dead.

He waited, face buried, the Winchester held vertical so water would not enter the barrel. The men reached the bodies, spoke, moved, and began to follow the tracks he had made—from the rocks to the crater—until one of them looked into the water and saw the eyes that watched him with something that was not hatred, not triumph, but a stunned recognition of another human face.

The man stood above him. John shot. Then he shot again. And a third time from a water hole that had been his shelter. He killed men who had come to collect their dead, and in the seconds that followed, the calculus of battle straightened like a clean board: the enemy became many. John ran and shot and ran and dropped into craters and kept moving until the current of the jungle pushed him back toward the American perimeter.

When he reached the battalion he smelled like the island—mold and mud and the metallic tang of the things that die. He was down to two rounds and had the look of a man who had been allowed to do what he was built to do.

“You cleaned it?” Captain Morris asked later, a gruff man who looked as if he’d been carved from the same tired wood as the island’s dead.

John had cleaned the Winchester for hours. Mud had crusted inside its action. The scope was gone; it had been removed at some point, trading magnification for portability. He kept the Lyman Alaskan with the rifle until division asked him to train others. Colonel Ferry, the regimental commander, came with a question: could he teach other men to become what he had been—silent, precise, a small machine in a human body?

He accepted because there was a need and because the alternative—doing nothing with what he had learned—felt like wasting a life.

He took men to a makeshift range two miles east of Henderson Field and taught them how to breathe so bullets would be gifts and not sins. He taught them to use logs and rocks as shoulders. He made them understand the weight of staying still. The army found fourteen Springfield sniper rifles in a room and, by February, had turned those into a regiment-sized idea of quiet killers whose task was not glory but survival.

They trained, shot, adapted. They were young men who had never seen a man lie still from a single round, who had not yet become acquainted with the sound of a rifle that delivered death as a single, surgical action. They killed twenty-three Japanese soldiers on a patrol once, and twenty-three became a number on a notice board. The snipers’ section, as John’s men, climbed toward professionalism with a kind of patient cruelty that war begot. They lost men to sickness as often as to bullets. The jungle recycled the living into the dying at a rate that made your stomach coil.

In Burma, the Winchester’s bureau of honors was less respected. The realities of long marches and resupply-less patrols required lighter weapons for longer distances. John sanded down the rifle, replaced the stock with a synthetic weight-saver, and swapped the Lyman for a lighter Weaver. The Marauders moved like shadowed ghosts across mountains and rivers, and the Winchester saw rare use—three times in three months. There were ambushes that were fifty yards or less, scrambles where the rifle’s single round wasn’t the point; the point was survival and making the march. The Marauders took Mitkina in May but paid for it with enough disease and fatigue to strip the unit to a skeleton. John came away with wounds to the shoulder that would mark him with a scar both physical and mental.

War, John learned, had a currency that did not care about heroism. It cared about results. His Winchester sat in a case at Fort Benning after the war and then in a footlocker after the Army discharged him. He used the GI Bill to go to Princeton and then Oxford. He studied politics because the world felt fragile and he thought a pen might be a steadier instrument for change than a rifle. He married, taught, worked at a think tank, and for years he told himself he was done with the small geometries of killing. He believed, incorrectly, that the act of living moving forward would blur the edges of his wartime past.

But ghosts are efficient in their persistence. He wrote because the details needed a ledger. He wrote not for applause but to record what worked and why: bullets’ behavior under humid air, scopes’ efficacy in canopy, the mathematics of patience. His manuscript became Shots Fired in Anger, and the book trafficked in technicalities; it did not glorify, but it did not repent either. It was, he hoped, a manual for survival that might spare a man from a worse death. He did not want it to be a manual of killing for any other reason than necessary defense.

The medals came as thin things wrapped in a gladness he did not feel. Bronze Star. Combat Infantry Badge. Purple Heart. He accepted them with the politeness of a man who knew the theater of honors was a poor substitute for a man’s face. He taught marksmanship to young officers at Fort Benning and watched as the corps became industrial in its logic—standardization, production, efficiency. He taught them skill and the importance of judgment. He tried, at odd hours, to tell them something deeper: that precision is a tool, not a moral argument; and that the cost weighed more than the count of dead across a ledger.

After the war, there were letters that pressed on the sides of his life. A parent sent a note, an old man in a Midwestern hall pressed his hand a little too tightly and said, “We heard about Point Cruz. Thank you.” There was also the slow theft of clarity—laughter at family tables that clinked because silence had been stripped of its rightness. In the quiet, John thought of the men he had shot. He looked at their names in official lists sometimes, tracing the way a name could shove a weight inside a chest and make it hard to breathe.

One winter in the late fifties, he received an invitation that he had not expected: a letter from a Japanese survivor who had heard, through a cousin now in Yokohama, about an American rifleman who had been precise in the groves. The letter’s English was careful. The man—Shigematsu—wrote that his brother had been a soldier at the time and had died somewhere near the groves. He wanted to know why John had shot. He wanted to know if a man like John thought that he had done the right thing.

John read it three times before answering. He could have written the language of justifications—orders, necessity, self-defense—but Shigematsu’s handwriting wanted something different. It wanted a human voice. So John wrote that it had been war and that he had been shooting at those who shot back, and then he wrote the part that he had been reluctant to say aloud: that every kill was a weight, and that he slept occasionally with that weight rearranging itself under his ribs.

They began to exchange letters. The cadence of their communication was like a plumb line across an ocean: shy, exact, and at the beginning quietly practical. Shigematsu wrote of a father who had kept a garden after the war, of rice that needed the steady hand of attention. He spoke of visiting cemeteries and scattering salt on stones. John wrote of Princeton tutorials and lectures at the foreign affairs institute, the way politics smelled like old paper and stubborn hope, the way he sometimes dreamt of banyans.

There came a time when John, who had moved through the hardcover of things with the careful kindness of those who survive to teach, traveled to Japan. He was older—sixty, then seventy—but travel in the sixties felt like something he owed to the men who had been made of his past. He met Shigematsu in a small tea house where rain tracked the slidings of the roof like an attentive chorus. They sat across from one another over porcelain and the conversation had the small formalities of two men acknowledging their history.

“You wanted to meet because…?” Shigematsu asked, neat and precise as a seam.

John saw the ghost of a younger man’s face in the older one—unwilling, then required to understand. He answered honestly.

“Because I wanted to look you in the eye and stop writing like a ledger,” John said. “Because I wanted to tell you that I am sorry for the men who died, and not for what war required, but for the cost.”

Shigematsu’s face held a slow translation. He nodded. “My brother,” he said, lower voice. “He was not a sniper. He was an archer in the local militia before the war. In the army…he became a rifleman because they told him that is what he was to be. We have a photograph. He is young. He smiles. The family pinned it on our wall.”

They spoke for an afternoon and into the twilight, about farming and books and the oddness of medals. Shigematsu told John about rice fields that kept seasons quiet by their need for steady attention. John told Shigematsu how he had put the Winchester in a footlocker and then taught men about the sanctity of the trigger pull. They did not avoid truth. They accepted it like an obligation.

When John returned to the United States, he found himself more willing to speak in a voice that conceded. He lectured on African affairs in the State Department’s Foreign Affairs Institute by day and, at odd evenings, took students aside to talk about what it cost to win a little battle. He wrote, too, because the lecture was never enough. He published Shots Fired in Anger not to celebrate but to instruct; to make a machine of knowledge that might serve men and keep them alive. He donated his rifle to a museum not to glorify his accuracy but because he could not carry that contraption inside him forever. It would be in a glass case now, preserved for the sake of remembering.

Later, old enough to see how history tends to simplify, he sat in a dusty auditorium and watched the way the museum’s visitors walked past the case. Most did not stop. The Winchester looked like any other hunting rifle under the light. When a child paused and looked up at the placard, John felt the run of his own life curled into chains of smallness: the boy’s eyes, the printed description, the tiny universe of a man’s decision, boiled down to a display.

He thought of the men whose lives he had taken and of the ones who had been left behind. He kept a private ritual: a small notebook where he had written every name he could recall. The act of writing them was a small repentance, a way of converting memory into visible ledger. He would sometimes place the book in front of the rifle’s glass and sit and watch reflections of himself bend like a prism. The public story said he had been a hero. He resisted that term. He preferred: necessary. He preferred: flawed.

In the quiet nights he sometimes dreamed of banyans. The trees in his dreams were patient and terrible, and he walked between them like walking between questions. He had no illusions about the clarity of memory. He knew that most narratives are tidy lies to keep pain company. He also knew that stories could change the world if people allowed them to be, in some surprising way, truthful.

On a warm morning in October, decades after Point Cruz and burma, John was sitting at a small table in a university cafeteria when a young man approached his seat. The man was a cadet at the ROTC program—a bright face, an earnest voice.

“Captain George?” the cadet asked, hands tucked inside the bag of a messenger strap like a soldier always keeps a part of posture. “I…we were reading some of your notes for the marksmanship class. I just wanted to—thanks.”

John smiled an old, private smile. “You’re welcome,” he said. There was something in the boy’s face that reminded him of younger men who had laughed and later watched as laughter shrank into survival.

“Did you ever regret it?” the cadet asked suddenly, with the bluntness of a young man seeking moral instruction in a world that had not yet taught him the complexity of it.

John paused. There were answers that belonged to outlines and answers that were worse: stories that sounded like absolution. He decided to be honest.

“Regret is a compass,” he said. “It shows you the places where you can do better. I regret many things. I regret not speaking to men about what it costs soon enough. I regret that a rifle sometimes felt like the only answer. But I do not regret that a man I loved—a man who had been shot—didn’t have to die slow because someone was able to stop the person who aimed at him. War’s full of those terrible trades.”

He taught that day and many days after his students about restraint and focus and the moral dimension of skill. They trained with emptiness in their eyes sometimes, and John taught them to carry an understanding: that accuracy without judgment was a dangerous thing. He taught them to count lives like the rare things they were and to consider the faces beyond the sights.

Late in life, he traveled again to Japan. Shigematsu had died within a decade of their first meeting, but his family continued an exchange that had started with letters and warmed into friendship. They walked together along a garden and exchanged seeds because small things—like seeds—helped people remember the seasons of their lives. At a memorial in Yokohama, John and Shigematsu’s eldest son stood by a stone that bore a name he had learned in a letter. He placed a bouquet of white flowers down and spoke softly in Japanese.

John, whose English kept the taste of islands in his mouth, returned the gesture with a hand on his heart. He did not seek forgiveness like a treasure to be won. He did what he could with the years given to him: he taught, he listened, he wrote, he apologized when needed, and he made sure that his rifle—kept safe in a case that was no longer his alone—would be something people looked at and considered: not a trophy, but a lesson.

In the end, the humane thing was not to say that one action had made him more or less than a man. It was to say that he had been a man who had learned, painfully and stubbornly, that the instruments of war are not moral in themselves. They are neutral until someone uses them. He had learned to weigh the use carefully.

At ninety, when his joints complained more than his memory and his hands had the tremor of old age, John slipped into a lecture hall at the institute and listened as a marine recounted a narrow escape where a bolt from a rifle had saved a life. After the lecture, a young Japanese woman approached him, a translator at his side.

“My grandfather,” she said, English measured with a clear tenderness, “was in the groves. He spoke of a man who fired like a craftsman. He later found it difficult to talk about it. He—he died in ’43. We have—” She hesitated, and then smiled a tired little smile. “We have your book in our house.”

John took her hand. He felt the century in his palm—a life compressed into an old soldier’s bones.

“Tell him thank you for tending the book,” George said. “Tell him you kept the story honest.”

She nodded. “He says it is a sorrowful book in parts, but it is true.”

They talked for a while, about rice and seasons and a rifle that now sat in a museum in Fairfax. When she left she handed him a note, folded small: a line of children’s drawings from a school in Yokohama that had visited the museum. The kids had drawn trees and people and rifles as they remembered them—some larger than life, some like humble instruments. One of the drawings showed two men sitting across from each other, a banyan tree between them. In marker, the children had written, in their fumbling English: “We remember. We forgive. We learn.”

John kept that note in the small leather book where he had once listed names. It was a small, fragile thing—a child’s earnestness folded into the weight of the world. He read it on nights when the dreams of banyans gnawed at him and felt a quiet comfort like a hand over a wound.

He died the way men who have lived long and kept their heads down in service to others sometimes do: surrounded by books and the careful attention of those who remembered his lectures, not his kills. At his funeral, neither a hero nor a coward, men and women spoke in honest terms about what he had done. Some called him brave. Some called him a man who had known how to do a task and completed it with skill. His son talked about the quiet hum of the rifle in their house, how it had sat in the footlocker because his father had always been careful with things that looked too much like victory.

The Winchester was placed in a glass case at the National Firearms Museum not as a monument to killing, but as a ledger of lessons. The placard beneath it read, in careful prose, of the man who had cleaned his bolt in a crater and taught others how to be precise. Visitors shuffled past the case daily, sometimes reading, sometimes not. Sometimes, when a child paused and asked, the museum docents told the story as best they could: of a man who had been mocked and then necessary, who had killed eleven snipers in four days and then lived a life in which those days became the ground of his lessons rather than the crown upon his head.

Years later, a Japanese delegation came to see the display. An elder bowed before the case, the crease of his hands measured and old. He laid flowers and spoke to no one in particular about loss and about the curious way the world kept asking for a ledger and offering instead colors of reconciliation. The museum curator told the story of John George with a voice that honored the man’s skill and his later humility. A small plaque was added nearby, written in both English and Japanese: “Remembering the cost.” It was a neat, small addition. It did not fix what had been broken, but it stopped people from walking by in ignorance.

The story that had begun with mockery ended not in vindication but in a complicated kind of satisfaction: the survival of the man who had become a teacher, the shared quiet between former enemies who had chosen, in those later decades, to write letters and plant gardens. Men had died; John had taken names and carried them like stones. He had learned that to live afterward was its own kind of work, a slow, deliberate art of making amends where you could.

If someone asked him once whether he felt like a hero, John would have found that question naive and too lean. A hero, he thought, is a simple commodity for children’s stories. He had been a man with a rifle when the world asked for men who could act. He had then been a man who learned to speak about the cost of action and to make space for mercy to live beside memory.

On quiet evenings, he would sometimes walk slowly to the museum and stand by the rifle’s case and watch his life reflected in the glass. He would see a man who had once been mocked and later had been necessary, and he would think of the men in the groves, of the voices that had come looking for their dead, of the young Japanese soldier who had bent over a stone with salt in his hands. He thought, finally, that the humane ending did not erase the violence. It simply asked people to remember that after the firing stopped, there was always the work of living: of teaching, of writing, of sitting with the dead and the living alike and learning how to bear both with a measure of grace.

And so, at the end, he left the world not as a poster boy for marksmanship but as an old man who had tried to turn his war into a ledger of lessons: technical and moral, practical and kind. In the museum, a child once asked, “Did he like the rifle?” and the docent answered without flinching: “He respected it. He respected what it could do, and he taught others that respect is as important as skill.”

That, John thought, listening from wherever he had gone after, was enough.

News

Unaware Her Husband Owned The Hospital Where She Worked, Wife Introduced Her Affair Partner As…

Ethan’s eyes flew open. He didn’t think. He didn’t weigh possibilities. He didn’t do the billionaire math of risk versus…

A Single Dad Gave Blood to Save the CEO’s Daughter — Then She Realized He Was the Man She Mocked

He pointed past Graham’s shoulder toward the Wexler family plot, eyes wide like they didn’t belong to him anymore. “What……

She Lost a Bet and Had to Live With a Single Dad — What Happened Next Changed Everything!

Behind him, two of Grant’s security men hovered near the black SUV, looking uncomfortable in their tailored coats like wolves…

She Thought He Was an Illiterate Farm Boy… Until She Discovered He Was a Secret Millionaire Genius

Then a small voice, bright with terror, cut through the hush. “Sir! Sir, I heard it again!” Grant’s eyes landed…

Come With Me…” the Ex-Navy SEAL Said — After Finding the Widow and Her Kids Alone on Christmas Night

Malcolm’s jaw tightened. People had been approaching him all week: journalists, lawyers, charity people, grief-hunters with warm voices and cold…

“Can you give me a hug,please?”a poor girl asked the single dad—his reaction left her in tears

Bennett lifted a hand and the guard stopped, instantly. Power was like that. It could silence a boardroom. It could…

End of content

No more pages to load