“You’re not going to quit, are you?” May asked as they walked back across the tarmac.

Jimmy looked at the sky as if it still contained the answer. “No. Someone has to make the sky smarter.”

When Jimmy presented the maneuver at the Bureau of Aeronautics, a man at the head of the table said it violated doctrine. A lieutenant called it a suicide ballet. Someone else tapped a medical report that catalogued a minor back complaint and a reading chart he’d failed to perfect twelve years ago. He could feel the room triangulate him, the angles of dismissal forming around him like a vise.

“So you want me to teach older men to fly like younger men,” said Captain Russell, leaning over the mahogany with an eyebrow raised.

“Younger pilots die because they have no system of mutual support,” Jimmy said. “This isn’t age—it’s tactic. It’s geometry.”

Vice Admiral John McCain stood in the doorway then, a weathered figure whose silence had the dimension of command. He read the diagrams like a man reading the tide.

“Does it work?” McCain asked.

“Yes, sir,” Jimmy said. “I’d stake my life on it.”

McCain looked at the others and, for once, the colored stars at the table seemed trivial. “Form him a test squadron. Four planes. He’ll deploy to the Pacific and prove it.”

The order came with a warning: don’t make me regret this.

Jimmy accepted the four men he asked to fly with him, not because they were the best pilots on paper, but because they were the kind of men who could listen without needing to be right every time. There was Richard May, brisk and skilled; John Carr, a boy made of quicksilver and luck; Howard Burrus, blunt and steady; and Ensign August Huxable—steady hands, quiet voice—whose combat report from later would forever tie his name to a certain day in Leyte Gulf.

They called themselves Division Four on the Lexington’s flight deck, and in the way sailors give nicknames to the untameable things they live with, they called the maneuver the weave. The press called it ridiculous. The Admiralty called it experimental. The men who flew it called it salvation.

The first real test was not a neat, clean engagement in which Americans had all the advantages. It was 0923 hours on August twenty-fourth, 1944, somewhere over the Philippine Sea, when radar blipped twelve Mitsubishi A6M Zeros converging from the northwest.

“Bogeys at 15,000,” the radio operator said with the blandness of someone reciting a weather report. For Jimmy, those words transformed into angles and relative velocity: twelve attackers, two pairs, and a geometry begging to be exploited.

“May, Carr—form up. Weave on my mark,” Jimmy said, voice a blade.

They crossed paths like two reluctant dancers. The Zeros attacked what they thought was a typical pursuit, but each time a Zero locked on someone the wingman would sweep perpendicular, firing as the target passed. The discipline required to keep from colliding—keeping precise spacing, throttle adjustments timed to the beat of propwash—was surgical.

Saburo Sakai, a Japanese pilot who survived the encounter and would write of it later, later called it like trying to shoot ghosts: unsteady lines and sudden intrusions into one’s aim by an airplane that shouldn’t have been where it appeared.

Four Japanese planes fell that day. Not a single Hellcat went down.

When the Japanese adapted and came again on the 27th with twenty-one fighters, convinced that they could counter the weave, Jimmy’s division held the line. The pattern tightened; the rhythm became less of a thought and more of a joint muscle memory. The enemy could not find sustained tail position. Seven more Zeros crashed.

Word spread faster than bureaucracy could dismantle it. By mid-September, the Navy found itself training squadrons in the weave. The kill ratios climbed like a tide against the old assumptions. The tactic saved lives—hundreds first, then thousands—and with every saved life, the question of who was too old to fight began to look foolish.

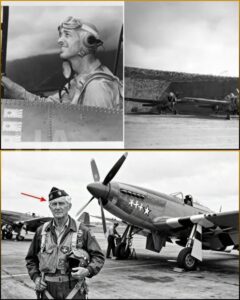

Jimmy Thatch, who had been labeled too old at thirty-eight, did not talk about being vindicated. He never wanted headlines. He did not like the way people fussed around heroic men with the same tone they used for incense at a funeral: respectful and unnecessarily loud.

He flew because the sky made sense to him. He flew because chess and algebra had taught him to see not just the piece in front of him but the space behind it, the trap, the counter. He flew because the tragedy of seeing a young man fall with a life in his hands could not be undone by more regulation.

But his vindication would not be simple. The war would teach him the cost of giving meaning to numbers.

On Okinawa in April 1945, the air was a furnace of intent. Radar blips multiplied into a blackening sky. On April sixth, what had been a line on a screen became hundreds of machines in the air: kamikaze pilots, living ordnance hellbent on ships below. Thirty-minute windows of chaos became eternities for the men on deck.

The Lexington’s crew moved with ritual precision: planes took off, rockets armed and pilots stripped of small comforts. Jimmy watched the horizon like a man watching the face of someone he loved go into danger. His back ached, the old pain a physical reminder that his body was not the engine it had been when he first took off decades earlier. His hands trembled from fatigue more than fear. Around him the world was younger—boys who had signed on for adventure, who had laughed at his age and now looked to him with trust that sat heavy in his eyes.

“Thatch,” May said, voice flat. He had the look of a man who’d stopped pretending at being a child. “We’re in for a storm.”

“Then we’ll be the umbrella,” Jimmy said. “Weaving pairs. Watch each other. Trust without looking for signs.”

He kept his speech short. Shorter than it had been in the Bureau of Aeronautics, because words were luxuries and time—a scarce commodity—was better spent practicing the rhythm in the engine’s roar than saying things into the wind.

They took off into the smoke. The sky above the invasion fleet boiled with enemy aircraft. The first waves of kamikaze found their marks—ships trembled and sank in sheeted fire; the Bismar Sea vanished in a blue bloom of burning oil and tearing metal. The destroyer Kimberly lost an entire bridge crew as if the ship had been struck by a meteor.

Jimmy’s Hellcat climbed into the sky as if into a theater where the acts had been written in an old book and where improvisation would decide the next scene. He scanned, pointed, and moved his division like a small orchestra playing for an audience of men and steel.

The engagements that week were a catalog of horror threaded with moments of crystalline bravery. An enemy plane came screaming down with an incendiary devotion and found its path intersected by the precise timing of a weave pair. The kamikaze’s running speed—calculated and committed to—met the sudden explosion of tracer rounds where a wingman had chosen to appear.

By the end of seven days between April sixth and April twelfth, the American fighters claimed 587 Japanese aircraft. Forty-three American fighters were lost. The ratio was an odd kind of comfort: a figure that could not make up for those lost but that meant some would live because others had aimed and breathed, counting seconds to the millisecond.

Jimmy’s personal tally in that week—twenty-seven confirmed kills—was an odd thing to publish on paper. It reduced to arithmetic the ugliness of making the decision to pull a trigger as another man’s plane became a human intent. After each engagement he filed reports with the methodical detachment that war demanded: angles, positions, times. He signed his name and thought of men who had not come back to write their own lines in the margins.

There were nights when the aftershock of that week took him like a tide. He walked the carrier alone, watched the sea and imagined faces in every flicker of foam. He kept a notebook in his footlocker, but for the first time in a long time the lines remained blank. What could he write that would mean anything? That he had done his job? That he had killed enough planes to make historians nod? The math seemed shallow against the black weight of grief he carried.

A letter changed the shape of that grief. It came in a thin envelope from a man named Robert Winston—a pilot Jimmy had never met in person, who wrote with a soldier’s directness.

“Sir,” the letter read, “I was shot down three times. Each time I survived because my wingman engaged the enemy before he could finish me. I have two daughters now. They exist because you refused to accept that you were too old to fight.”

Jimmy kept that letter folded inside his wallet. He read it when the ship rolled and the world seemed to tilt toward a horizon of ash. That letter said what a medal never could: that some math was not about kill ratios but about the geometry of children’s lives.

When the war ended and the guns fell silent, Jimmy refused interviews. He refused invitations to speak at airports named for men who had died. He took no money for the patent of the weave—if you could patent a motion—and he allowed no biography to be written. He accepted promotions because they were a duty, not a temptation. He returned home twice, briefly, to a wife whose letters had been as steady and patient as the sea, and to a small house that smelled of lavender and the ordinary business of living.

He believed that heroism—if such a word could be applied to anyone who had ordered men into danger—was not a commodity to be traded on a magazine stand. He believed it was a quiet persistence: the learning of a sequence of movements, the repetition of trust, the insistence that knowledge was worth a shot at survival.

At Pensacola and Corpus Christi, at Jacksonville and Alameda, men were taught to trust each other. The weave became not just a maneuver but a philosophy: two men who knew that the moment a comrade fell the world would be irrevocably worse; two men who accepted that computing an angle and making it work could be the difference between life and death; two men who would not allow a younger generation to be the only bearers of risk.

But the story of Jimmy Thatch was not there exclusively for the military. It was a small example of a larger lesson, one he would try, in the quieter decades of his life, to embody for his daughter and for the young men he met in town who’d run into the office wanting to fix drains or build a radio.

He learned to sit in rooms where the authority demanded a kind of deference he refused to give, and he learned how to be patient while waiting for an idea to find its moment. He walked through bureaucracies with the careful gait of a man who’d learned that sometimes persistence is more effective than temper. He didn’t need to be right in every conversation; he needed to be ready when a problem presented itself in a way his head could solve.

Late in his life, on an autumn afternoon in 1979, he sat in a small café in Annapolis and listened to a young woman talk about being dismissed because she was a woman and because she liked machines. She was bright, her eyes darting, and she kept pausing as if she wanted to ask permission to say something that might not be welcome.

“You’re no longer the kind of people who get to make lists of who can and can’t,” Jimmy said when she had finished, words thin but precise. He told her the story of the weave, not in technical terms but as a parable. “There will always be people who will tell you you are too old, too young, too queer, too plain, or too whatever. Their lists are the smallest kind of thing. They measure the world as if it fits on paper. It doesn’t. Look for the geometry in the margins.”

She laughed softly, incredulous. “You made a whole tactic sound like a moral.”

“It was a moral,” he said. “It was a decision to look at each man as a point on the map with others around him, not just a single moving target. That way you survive. That way you bring people back home.”

When he died on April fifteenth, 1981, the obituary in The New York Times was simple and brief: a man with decorations, a long career. The list of what he’d changed—thousands of lives saved, a soldier’s life reduced to a note—was missing because the public record has a way of forgetting things that are uncomfortable or complex.

At Arlington, in a rain that turned faces to small, hard things, two hundred and thirty-seven aviators—men in suits and medals and bones of remembered storms—stood and saluted. They remembered him not in the antiseptic terms of an obituary but in the wet geometry of memory: the way he had taught them to move when the sky darkened, the voice of a man saying “On my mark” with the quiet authority of someone who had spent his life measuring the angles between danger and rescue.

Michael Harris, a captain now more creased with years than his uniform allowed but with a voice steady as the latencies of a plane at cruise, spoke at the graveside. “We were told we were too old, too slow, too obsolete. He proved that wisdom beats youth, that thinking beats reflexes, that one man with the right idea can save thousands.”

He paused. Rain softened the words. “You taught us that the most dangerous thing isn’t the enemy. It’s the assumption that we already know everything.”

Thousands of pilots returned home because of the weave, because two planes could be more than twice as strong as one. Families were reassembled, births were celebrated that might never have happened, and the geometry of survival found itself baked into training syllabi for decades.

For Jimmy, recognition remained a cold spark at the edge of a life quietly lived. He was awarded the Navy Cross, the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Legion of Merit. A medal is a narrow thing to strap on a chest. He kept his medals in a tin in his attic, along with the letter from Robert Winston folded like a benediction. He read it sometimes and thought of the two small girls who existed because someone had been willing to compute the odds differently.

If he had a regret it was the men he could not save. He beloved numbers but he knew their limits. There were faces he could not recall without a sting—boys whose stories were told in stifled ways by mothers and wives who had to find themselves again in homes where a chair never emptied and a pipe never came back to the table.

Still, his life argued for a particular tenor of courage. It suggested that innovation was often the property of people who had lived long enough to see patterns others did not. It argued against the neat and tidy lists of who ought to be permitted to act.

“You were always different,” his wife once told him on a night when the thunder of storms in the distance sounded like older wars. “You always saw things like a puzzle.”

“I never liked puzzles where the pieces were thrown away,” Jimmy said. “If a piece fits, it fits.”

At his funeral a young pilot—still with the shine of youth—handed Jimmy’s daughter a folded piece of paper. Inside, a sketch of a weave, clumsy and earnest, with a note: “For your father, who taught us to fly for one another.” She folded it into her palm and felt, for a second, that the geometry reached beyond the planes and into people: a diagram of relationships, of mutual trust stitched into the sky.

Years later, instructors would tell the story of Jimmy Thatch not as scripture but as anecdote: the balding man with reading glasses who had dared to suggest that two men could be more than twice as safe if they moved like parts of the same organism. Some would read him as proof that age was irrelevant; some would read him as a footnote in a larger manual. The ones who mattered—the boys and girls who learned to fly and to watch each other—would carry the maneuver in their fingers as a palp, an instinct.

Sometimes the stories become simplified. Historians would parse and quantify and make neat ratios out of what had been a chaos of human choices. But in the marginalia of his notebooks, among graphite smudges and careful arcs, Jimmy had written one line that never made it into official reports. It was not technical. It read: “Trust the man beside you. Learn his rhythm. He will save you.”

There is a kind of heroism in that instruction because it asks for a softer, humbler bravery—the willingness to give someone else the right to be your survival. It is not as celebratory as headlines. It is quieter. It is human.

Once, late in life, an interviewer pushed him—a young man, earnest and hungry for a story. “You shot down twenty-seven planes in a week,” the interviewer said. “You changed the rules. How does it feel to be the best?”

Jimmy looked out at the water and shrugged. “We did what we had to do,” he said. “We found a way for men to come home. That’s the only record that ever mattered to me.”

The interviewer wanted more: “Aren’t you proud?”

“I’m proud of the men who trusted me,” Jimmy said. “Pride is a complicated thing. You can puff it up until it suffocates you. Better to let other people keep it than to take it from them.”

He died with that humility intact. People remembered him for the headlines he didn’t write, for the medals he wore only when necessary. They remembered him for a small, stubborn fact: a man marked by time can make the world safer by thinking differently.

When I was a child, my father pointed at a faded photograph on the mantle: a man with glasses, a small smile, a face that did not seek attention. He had the look of someone who had been tested and had chosen, with a quiet ferocity, to be kind when kindness was measured by whether you brought someone back from the edge.

“Who is that?” I asked.

“That,” my father said, “is the kind of man who proves we’re never too old to learn. He shows us that sometimes the smartest thing we can do is to stand close and watch each other’s backs.”

Jimmy Thatch’s story is not only about airplanes and geometry and statistics. It is about the lethal arrogance of thinking expertise is the same as understanding. It is about the ways bureaucracy can blind itself to possibility, and the stubbornness required to persist anyway. It is about the men who go into the sky—young, old, and all the shades between—and somehow find one another, mid-air, and choose to live.

If you look carefully at manuals of modern fighter tactics, if you read them with the patience of someone tracing a line across a map, you can find, in the margins, the ghost of a weave: two lines crossing, a small circle where bullets met, and a note that says, in the hand of a man who preferred quiet: “Keep your partner close. He will be your salvation.”

And if you are ever told you are too anything to make a difference—too old, too quiet, too flawed—remember the geometry of James Thatch: that an idea, practiced patiently and trusted by others, can change not only the way we fight, but the way we live. Remember that someone dismissed as obsolete may simply have the kind of patience that lets him see patterns others miss. Remember the man who made the sky teach us how to protect one another—and taught generations that saving a life is an equation worth solving.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load