That night, sitting on the floor with the lamp and the photograph, I decided to pull at the loose thread.

The ledgers were mundane at first: credits and debits, dates, names of local suppliers. He’d run the small grocery with his brother for many years — Sterling’s Market, the kind of place where your name was known and the owner knew when you needed a bag of flour on credit. But deeper in, beneath the grocery entries, someone else had been using the same ledger to type letters — official ones — and tucked into the middle were personal correspondences, some unsigned, some marked with acronyms I didn’t immediately understand.

One letter had a Navy seal in the corner and was typed in a manner that suggested formal restraint. It spoke of “temporary assignment,” of “special orders,” and of a “commendation for conduct.” My father’s handwriting — the one I knew from grocery invoices and notes to my mother — had scrawled next to the typed paragraph: “Not much to tell here.”

Another letter from 1950, where the type mentions “Korea,” left a gap at the bottom where the signature should have been. My father’s note there read: “I went. Ask Ma if you want more.” Ma had always been the easier archive — she kept the photographs, the trinkets, the social proof of life. She kept also the silence, but in a softer way. She had always been the heart; he, the hinge.

I continued to read. The pages shook the bones of my childhood memories loose and rearranged them. There were passes and furloughs and a brief telegram that announced a birth — my brother’s birth, the joy wrapped in monosyllables. There were also references to men he had served with, names that conjured faces I’d never seen. There were lines like “safety of unit” and “reassignment due to operational needs.” There was a notation I did not expect: “AWOL? Not quite.”

That last line made me sit back.

I had always known him as dependable, as someone who kept his promises even to strangers. The suggestion that he might have stepped outside of the expectations of duty for a period — however ephemeral the word AWOL — unsettled the tidy mosaic I had built.

I found myself on the phone before dawn, the photograph in my hand like something alive. I dialed my sister Jenna, who lived three towns over and seemed to carry more of Ma’s memory than any of us.

“Do you have any of Dad’s old letters?” I asked, trying to keep my voice even.

“For the thrift store? Or the museum you’ve decided to be?” She laughed, but the laugh softened. “No, why? Did you find something?”

I told her about the photograph and where I found it. We made a plan to meet at the house that Sunday. Between the two of us, maybe the ledger would open like a map.

On Sunday, Jenna arrived with a casserole and a tote bag brimming with items from her attic: a glove that smelled faintly of cigarette smoke (Dad didn’t smoke, but his brother did), our old Sunday-school photos, a rusted Boy Scouts pin. She carried with her an appetite for family archaeology. We sat at the kitchen table, surrounded by the slow ticking of an old clock that had belonged to my grandparents, and began to piece together the margins.

There was a particular letter that Jenna pulled out with fingers that knew which things were delicate. It was folded thrice and tucked inside a dog-eared copy of “Tales of the Sea.” On the outside, in my mother’s handwriting, was the name “Arthur — Read after.”

“Read after what?” I asked.

“After he told you,” Jenna said. “She meant: read it after he decides to tell you the rest.”

We unfolded it. The letter was not a soldier’s letter home; it was typed on Navy stationery but written with the rhythm of someone trying to make sense of a sentence at the end of a long watch. It spoke of an operation where he had been assigned to transport a group of refugees off an island — civilians caught in the crossfire — and of a subsequent disciplinary hearing that never quite landed. The language was careful, but someone had smudged a tear on the margin and the type bowed like a man who had been forced to stand in the rain too long.

“He saved them,” Jenna whispered, though the letter never used the word. “He didn’t follow orders because following those orders would have left people behind. He—” she stopped, then added, “He always said it wasn’t his story to tell.”

The ledger, I realized, had been a ledger of choices. It had the civic accounting of a life: groceries sold, milk delivered, names on a whisper of a page. But the margins held the currencies of another ledger: choices made in a place where there were no receipts and where courage and reckoning were more complicated than commendations.

As the afternoon unspooled, we found more pieces: a photograph of a group of men in Navy whites sitting on the hull of a ship, laughing as if they were unaware of what would come later; a small, folded map with locations circled in a handwriting that could have been my father’s — all that remained of decisions that had been made in the dark.

That night, back in my own house, I could not sleep. The picture I’d found had become a hinge. It swung me back to other nights: Dad at the top of the stairs watching television with the remote in his pocket like a talisman; his hands thick and sure, the knuckles marked by years of turning grocery boxes and turning soil in the backyard. I thought of the way he would read the Bible on Sunday mornings, his lips moving over phrases without his head nodding, the kind of private prayer that is a person’s slow work.

What had he carried inside him, and what had he given up?

The ledger suggested an answer, but it was only a suggestion. I needed the rest of the story.

I called Reverend Paul on Monday. He had presided over both of my parents’ funerals and had a patience for frayed histories. Over a cup of coffee in his office, he reached into a drawer and produced a transcript of interviews he had recorded years earlier when my father had been a deacon and had, in his small way, confessed to a number of parishioners that he had done something he felt unprepared to say aloud. The parish had been a church of small congregations and long loyalties; stories, once started, were shared over casseroles and coffee.

“He wouldn’t say it to the public,” the Reverend said, “but he told me once — when you were small, I think — that he had made a choice during the war. He didn’t say the details. He only said, ‘Sometimes the right thing is not the right thing to keep your job.’” The Reverend’s eyes crinkled. “He was worried about the family.”

Family. It returned as a precise, luminous object. He had been worried about keeping the family whole. He had been worried about jobs and food and the house that would one day belong to us. He had been the kind of man who put the safety of his family ahead of the thrill of his principles, but sometimes his principles would not be contained by thrift or necessity. They leaked into his choices.

I began to understand — not completely, but enough to see the outline. There had been a decision, a refusal to turn away from people who needed help. There had been consequences: whispers, a frozen promotion, perhaps a formal reprimand. But in return, there had been a life that built a church and a grocery store and leaned into Sundays like a shelter.

This is the ugly arithmetic of human life. What does a man owe his country? What does he owe his spouse? What does he owe a stranger whose life is at risk?

My father had tried to satisfy all ledgers at once. He had been merciful in a place where mercy was not required by regulation. He had been a hero in a small, unstated way because there are heroes who never appear in the headlines. There are men who are brave and quiet; they are the ones who fold their courage up into pockets of ordinary days and hand it to their children at breakfast.

Understanding this made me angry for a moment — anger at the systems that force people to make such moral math. Then it made me proud.

We are trained to look for dramatic tight bows: a glaring act, a televised apology, a public parade. But sometimes the bow ties itself in the dark, in the kitchen, over a dish of mashed potatoes, with someone who refuses to let another person sleep under an asteroid of fear. My father’s acts were sewn into the seams of his life; they were not loud because there was no need for noise. He loved his country — he loved his family. He loved also, evidently, a stranger in need.

The weeks that followed became a slow pilgrimage through our family archaeology. Letters led to names, names led to obituaries in crisp newspapers bound in the attic, and obituaries led to one or two surviving relatives we could reach. We found a man named Cho, who had been a refugee and had been transported to safety on a small vessel in 1950. He remembered a bearded sailor who whispered to him in broken English and who had offered him a cigarette and a blanket. He remembered that the sailor had risked his leave to keep the men on board while the commanding officer insisted on strict protocol.

“I suppose he saved us,” the man said through an interpreter, decades later at a reunion held in a community hall, his hands shaking as if he still felt the draft of the ship. “We were scared. He smiled and said, ‘Go home. Make babies. Work hard. Forget me if you must.’”

That is a sentence I had no right to hear and yet could not avoid: “Go home. Make babies. Work hard. Forget me if you must.” It was the kind of command that becomes prayer when uttered in the belly of fear. I thought of my father at the sink, washing dishes, his head bent. I thought of him on the golf course, adjusting his stance as if to order himself to be still. I thought of the small, ordinary mercy he had paid forward into the world.

The reunion gathered three generations. We all listened to Cho and to the handful of men who still came to the memorial for veterans who had been displaced after the war. They spoke of gratitude, of small kindnesses that had lasting effects. Some had left the region and taken positions in bustling cities; some had remained and built businesses that now fed their grandchildren. Memory works this way: a single act can map itself across time.

After the reunion, a younger man — maybe the grandson of one of the refugees — approached me in the parking lot. He had my father’s face in his eyes, an uncanny echo. “Your father saved my grandfather,” he said. “I want to say thank you.”

“You already did,” I said, suddenly embarrassed by the formalities of gratitude.

“No,” he persisted. “My grandfather couldn’t give thanks enough. He said to me when he got old: ‘Never forget the man who let us go home.’” He sighed. “So I’m saying thank you on his behalf.”

Words like that travel cleanly out of the mouth and settle like a benediction. We all arrange our lives around stories. Sometimes the story is that our father was a man who made dinner on Thursdays. Sometimes the story is larger: a man saved others amid the terrible choreography of war while he also tucked his children into bed and mowed the lawn.

Learning more about my father’s decisions changed my own internal ledger. It softened petty complaints, nudged me toward generosity. It also complicated my admiration; I could admire him and forgive him for the small selfishnesses that sometimes come with the aging of a person. He was not perfect. He was someone who sat with the enormity of choice and chose, again and again, to keep his family, and also to keep his humanity.

Years later, after I had children of my own and carried my father’s photograph in my wallet as if it were a small talisman, my son Henry asked one spring afternoon why Grandpa always looked so steady.

“He had a job that many people couldn’t do,” I told him, not wanting to get into the trenches of war with a six-year-old but wanting him to sense the gravity. “He loved people. Sometimes loving people means you have to be brave.”

Henry considered that, mouth full of apple, and then asked, “Was he scary when he was brave?”

“No,” I said. “Brave can be kind.”

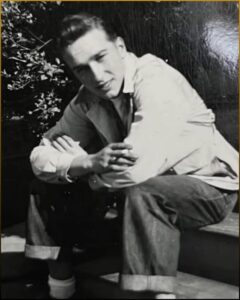

There are bright, cleaving moments when private things become public. For my father, the public outline of his life was always simple: groceries, church, swing sets, Sunday dinners. But the private depth had widened like a river after a storm. The photograph I had found — the one with the Brylcreem and the clean-shaven jaw — was the surface, laughing as a boy onto a future. Under the surface, the currents were stronger.

At his funeral — and his funeral was a community affair; a hundred people filled the pews, not because they had to but because they wanted to — people spoke of his steady hand and his tendency to pay for strangers’ items at the register. A neighbor remembered him showing up at dawn to cut down a tree that was threatening an old woman’s roof.

“Always right,” one of his old coworkers said, voice hoarse. “Always right.”

I thought about the ledger again — the ways we keep accounts outside of banks. There are people who hoard, and there are people who trade in trust. My father’s currency was kindness. In the end, he had been rich where it mattered.

After his death, we found a small box tucked under a floorboard in his workshop. Inside were letters from men he had helped over the years — simple notes folded with economy, thanking him for a night’s sleep, for a loan, for letting a boy sweep the floor and learn discipline. They were not the kind of letters that demand recognition; they were the kind that carry normal human gratitude like embers in a pocket. When the embers are fanned they make warmth that surprises you long after the fire has ended.

At my mother’s funeral, Jenna read a note my mother had left for my father. In it she wrote about the quiet life they had shared, seeded with loyalty and small joys. She mentioned the photograph — “the Brylcreem one” — and said, “I always liked his shoes in that picture.” Laughter rippled through the room.

I realized then that our parents’ lives were stories layered upon stories, and that the simplest sentence could sit on top of centuries of choices. A marriage that began in seventh grade carried with it the weight of decisions neither of them would fully explain. They behaved as people do who keep their promises: by being there.

On a humid morning many years later, when I was older and the house felt like someone else’s memory, I found myself at the kitchen table with Henry, who had grown into a curious adult with my father’s steady hands. He had been asking me about legacy — not the abstract kind, but actual things: what to keep, what to toss, what to give to the grandkids. He had my grandfather’s photograph in his hand, tracing the crease.

“What’s his real name?” Henry asked. He had always called him Grandpa Arthur, but I knew my father’s full name like the incantation in a family bible: Arthur James Sterling.

“He was… complicated,” I said, smiling. “He was a man who loved people in ways that mattered.”

Henry looked at the photograph. “He looks like he could have been a movie star.”

“He thought so once,” I admitted. “He had that kind of jaw.”

We sat with the photograph between us. Outside, a train sighed across the valley. The world had a habit of moving on despite everything. It surprised me then how much of my father lived in small, immovable things: a receipt, a grocery list, a prayerbook, a photograph.

I told Henry about the ledger and the refugees and the man named Cho. He listened the way he always did: with interest without the urge to fix everything. He is my father and my son and my mirror, and he had my father’s patience.

“So what do we do with it?” he asked, meaning the photograph, the ledger, the weight of history.

“We keep it,” I said at once. “We tell the stories. We name the people who were saved. We make sure that the choices he made get their small measure of recognition — not because we want to unfurl him on a banner, but because we need to keep the ledger honest.”

“Do you think he’d like that?” Henry asked.

I thought of my father in the yard, the way he would stop sometimes to look at the sky, and the way he preferred to give without attention. “Yes,” I said. “He’d like that. He never wanted to be known for one thing alone. He wanted us to be good. He wanted us to be useful.”

We made a plan then, a modest one: to donate the ledger to the local historical society, not as an exhibit but as a document of small lives. We would not dramatize his story. We would curate it as a fragment of a larger narrative: a man who lived across eras and decisions and who, in a single night on a ship, had chosen to be more than a rule-following cog.

As we drove to the society to drop off the ledger, I watched Henry drive with a care that reminded me of my father’s patience. He parallel-parked like Dad, always a few measures slower than most. The sun made small coin shapes on the dashboard. I felt, in a way that surprised me, both orphaned and rooted.

Years fold in on themselves. The children grew, careers took turns, summers shifted. But memory is a stubborn thing, and once you narrate it aloud, it rearranges the present.

One winter night when Henry called from across the water — he was living three states away then — he said, “Grandpa’s photograph was in my pocket today. I took it to a meeting. Someone said, ‘That man looks like someone who could be trusted.’ I said: ‘He was. He was more than that.’”

There is a small comfort in that transmission. The knowledge that someone from a lineage you respect might also be recognized by the stranger across town is a remittance. You pass to the next person not money, but a story that clarifies values.

When I finally visited the cemetery where he and Ma lay under the same oak, the air smelled of wet leaves. The headstones were modest as they had wanted. I sat on the grass, the photograph in my palm, and spoke like a simple liturgy: Thank you. Forgive me for all my small grievances. If there is anything I can do for you now, it is to be as kind as you were.

People sometimes imagine that the dead are set like copper coins in a drawer, finite and untouchable. But that evening, under the long branches that made lace against the sky, I felt him more like a riverbank: fixed enough to be known, but always responsible for the flow. He had given us a map of what mattered — decency, the willingness to help, the steadiness to show up.

There was one more fragment we found years after his funeral tucked in an envelope labeled in my mother’s hand: “Arthur’s reasons.” It was a short note in his thick script, written on a pad from the grocery store. He had been known to write things down when he thought they might slip. The note read:

If a nation asks us to do things that make us less than human, refuse them politely and find another way. Family must be fed, yes. But there are ways to feed family that do not starve the soul.

It was not the kind of manifesto that changes policy. It was a man’s last testament to his children: live with conscience. The paper, crumpled and plain, made the house smell of old paper and the evening before the holiday. I smoothed it and slid it carefully into my wallet, where it kept company with a business card and a photo of Henry as a baby.

There is an art to living well that my father practiced without fanfare. It involves listening to small, inconvenient nudges in the mind and making choices that honor the persons you love and also the strangers you do not know. It involves a readiness to explain without demand and a willingness to be accountable.

When the world grows loud and complicated, I often recall his hands at the sink, the way he would scrub a plate until it shone as if it were a mirror, because in the mirror you could see the person you were becoming. He did not live a life of broad proclamations. He lived a life stitched from modest, necessary stitches. Those stitches were his form of prayer.

Sometimes I take the photograph out of the drawer, hold it to the light, and imagine the mancub in the navy whites who believed he might look like a movie star. The crease in the lower right is where a man once folded his future and slipped it into his pocket. If you stand still long enough, you can catch the echo of him laughing at his own vanity as he straightened his Brylcreem. He went on to mow lawns and pay mortgages and tell us to say “please” and “thank you.” He carried kindness like a badge.

When I think of him now, I do not inventory his flaws. I count small, generous acts. He taught us that love is not a headline; it is a long collection of moments stitched together: showing up on school mornings, saying sorry, returning a borrowed tool, letting a stranger sleep on your floor when there was cold outside. He taught us — by example — that bravery looks a lot like humility.

I put the photograph back into the drawer and closed it gently. The house seemed content with the small order of things. My father’s life was not one that razed mountains. Instead, he smoothed the ground for those who would come after, turning hardship into soil for the future. The photograph will likely find its way into another hand one day, into another pocket. Maybe Henry will tuck it into his wallet, maybe his children will ask about the Brylcreem and the neat jaw. Maybe one of them will sit under an oak and feel the river bank steady beneath their feet.

For now, I keep the ledger on the shelf and the note in my wallet. I tell the stories — not because I seek to sanctify him, but because the stories instruct. They show how a small life can perform acts that, in total, become a legacy.

When I think of him I feel, first, gratitude: for the man who took the risk to keep others safe even when the rules snarled him up. Then I feel the quiet happiness of someone who knows they grew from a good root. He wasn’t perfect. He had small, human flaws. But when it counted, he did the right thing.

At night, when the house is quiet and the lamp throws a pool of light on the table, I take the photograph out and look at the young man who, with perfect hair and hopeful eyes, thought the world would reward him for being brave. The world does not always reward you, I realize, but it sometimes returns beauty in the form of lives that were saved and children who were taught what matters.

That, I think, is the true reward: to have loved and to have been loved back into the world for our betterment. I slip the picture back into the drawer, close it and lock it with the habit of a man who still keeps some things for safe keeping. Then I go upstairs and say goodnight to the house.

On the kitchen table sits a card my son sent me last week. On it, in hurried letters, he wrote: “He was brave. You gave him to us.” I hold the note and think of the man in the photograph, of the ledger, of the countless little mercies my father offered. I think of how we measure a life and realize that the scales were never heavy with fame. They were balanced by the weight of ordinary courage: the readiness to be present, to choose kindness, to risk for the sake of another.

Outside, the neighborhood settles into quiet. A wind bends the branches of the oak and carries away the last of the leaves. I sleep better knowing he is where he always wanted to be: beside the woman he loved, in a world that, for all its flaws, remembers the small things that make us human.

News

End of content

No more pages to load