On the first Sunday of November 1923, the fog came down into Beckley Hollow like a living thing. It slid between the company houses, wrapped itself around the chapel bell tower, and settled in the lungs of the valley. Coal dust mixed with wood smoke, turning the air heavy and metallic, the smell every miner knew before he ever learned to read.

By the time the chapel bell rang, men were already lining the dirt road, boots scuffed, shoulders stooped, faces gray not just from coal but from years of work that paid barely enough to survive. Winter was coming. Everyone felt it. Everyone feared it.

That morning, Cordelia Thain stood at the back of the chapel, hands folded, eyes lowered, dressed in black as she had been since her husband died eighteen months earlier. She had aged quickly, or so it seemed. Her hair, once chestnut, was now streaked with iron gray, pulled tight into a bun secured by old bone pins. She looked like grief made solid.

After the final hymn, she approached Reverend Josiah Merkel.

“Reverend,” she said quietly, “may I have a word?”

They spoke in his small office behind the altar, a room that smelled of old books and candle wax. She explained her idea with calm precision.

“I wish to prepare soup,” she said. “Every Sunday. For the miners. For their families. Free of charge.”

Reverend Merkel studied her face. “That’s a generous offer, Mrs. Thain. But it’s no small undertaking.”

“I’ve done the sums,” she replied. “My husband left me enough.”

She did not smile. She did not cry. She simply waited.

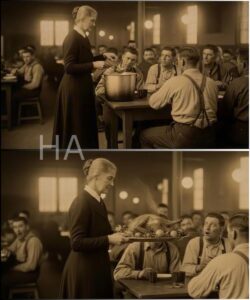

By the following Sunday, the church basement was transformed. Long tables had been scrubbed clean. Large iron pots steamed gently atop coal burners. Fresh bread sat wrapped in cloth, still warm to the touch.

Cordelia herself ladled every bowl.

“Bless you, ma’am,” a miner said, holding out his tin dish.

“You’re welcome,” she replied, watching carefully as the soup filled the bowl. “Eat slowly. It’s meant to last.”

The soup was extraordinary. Thick, rich, deeply satisfying in a way no one could quite describe. It filled the belly and warmed something deeper than hunger.

“This is better than my mother’s,” one man laughed.

Cordelia tilted her head. “High praise.”

She watched him eat.

That first Sunday, thirty people came. The second Sunday, nearly fifty. By December, more than sixty crowded into the basement each week. The Sunday soup became a ritual, something people planned around, something they talked about all week.

And Cordelia never missed a Sunday.

She arrived early, always with the same hired man, a drifter named Caleb Wickham. He carried the pots without complaint, eyes down, hands steady. He spoke only when spoken to.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“No, ma’am.”

Some noticed that he flinched if she raised her voice even slightly.

Others noticed stranger things.

“She won’t let anyone help serve,” whispered Geneva Caldwell one afternoon. “I offered. She refused.”

“She watches us eat,” another woman said. “Like she’s counting.”

They laughed it off. Grief made people odd. Kindness earned patience.

Winter tightened its grip. The mine shut down more often. Money grew scarce. Hunger crept into homes like an uninvited guest. And always, on Sunday, there was soup.

It was during February that the first man vanished.

Hezekiah Drummond did not come to work Monday morning. His room at the boarding house was untouched. His money was still hidden beneath his mattress. His boots were clean.

He had been at the soup the night before.

“Probably took off,” Constable Doyle said, scratching his beard. “Men do that.”

Three weeks later, Fergus McCreary disappeared. Then another. Then another.

By June, seven men were gone.

Reverend Merkel began to write in his journal at night, hands shaking.

They do not vanish like this, he wrote. Not without reason.

He watched Cordelia more closely now. Her grief had changed. She seemed energized. Alive. Her eyes were bright in a way that unsettled him.

“I’m so sorry about Mr. Whitmore,” she said one Sunday, when told of another disappearance.

Her voice was calm. Practiced.

“Did he seem ill when he ate?” she asked softly.

The question lingered in the air too long.

Silas Harrington noticed it too.

He was a foreman, respected, methodical. He had lost men underground before. He knew patterns.

“She gives bigger portions to the men who live alone,” he told his wife Martha one night.

Martha frowned. “I thought I imagined that.”

“I saw her near the abandoned shaft before dawn,” he said quietly. “Carrying something heavy.”

They stopped going to the soup.

In October 1924, Cordelia expanded her generosity.

“I’ll host meals at my home,” she announced. “For men working long shifts.”

Five men accepted the invitation.

They never came back.

This time, the mine shut down. This time, the sheriff came.

Sheriff Clayton Bosworth was not easily shaken, but the well behind Cordelia’s house changed him.

Bones. Clean. Sorted.

A ledger behind a false wall ended all doubt.

When confronted, Cordelia smiled for the first time anyone could remember.

“You’ve eaten well,” she said calmly. “All of you.”

Her confession was meticulous. Efficient. Terrifying.

“They were lonely,” she said. “No one would miss them right away.”

“And your husband?” the sheriff asked.

Her eyes softened. “He was the first.”

The trial drew crowds from across the country. People listened in horror as they learned what they had consumed.

“I praised her cooking,” one miner sobbed on the stand. “I thanked her.”

Cordelia showed no remorse.

“I gave them comfort,” she said. “In life and after.”

She was sentenced to die.

She never made it to the chair.

They found her in her cell, poison at her lips, a note beside her hand.

The recipe dies with me.

Beckley Hollow never recovered.

Families left. The church was torn down. The mine closed. The forest reclaimed the valley.

Years later, an old man named Ezekiel Carpenter spoke to a historian.

“We were hungry,” he said. “And someone fed us.”

He stared at his hands.

“That’s how evil gets in. It doesn’t break the door. It waits until you open it yourself.”

On Sundays, some hikers say the air still smells faintly of soup.

And somewhere deep in the hollow, the silence remembers.

News

The Maid Begged Her to Stop—But What the Millionaire’s Fiancée Did to the Baby Left Everyone Shocked

The day everything shattered began without warning, dressed in the calm disguise of routine. Morning light spilled through the floor-to-ceiling…

In Tears, She Signs the Divorce Papers at Christmas party—Not Knowing She Is the Billionaire’s…..

In Tears, She Signed the Divorce Papers at the Christmas Party — Not Knowing She Was the Billionaire’s Lost Heir…

My Wife Took Everything in the Divorce. She Had No Idea What She Was Really Taking.

My Wife Took Everything in the Divorce. She Had No Idea What She Was Really Taking When my wife finally…

Susannah Turner was eight years old when her family sharecropping debt got so bad that her father had no choice

The Lint That Never Left Her Hair Susannah Turner learned the sound of machines before she learned the sound of…

The Gruesome Case of the Brothers Who Served More Than Soup to Travelers

The autumn wind came early to Boone County in 1867, slipping down the Appalachian ridges like a warning no one…

Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

The Hand That Refused to Disappear The afternoon light in Riverside Antiques arrived the way it always did: tired, slanted,…

End of content

No more pages to load