At first, some folks in Odd wanted nothing to do with cameras. They remembered older men who had showed up with rusted curiosity and left with gossip. They saw the Whitakers as part of their own weather, a bitter current that had always been there. Protecting them wasn’t pity; it was neighborliness. Or perhaps it was fear. Once you started looking, you might find the same pattern in other families. And if you shone a very public light on the Whitakers, would the light stay on the Whitakers? Or would it reveal how thin the safety net of places like Odd had always been?

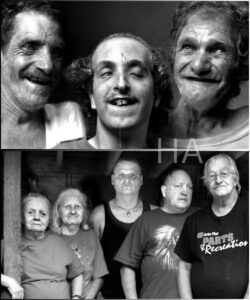

Mark leaned on the porch rail one gray morning while Lorraine fed a skittish two-year-old who belonged to Brandon, a Whitaker by name but determined, in a small, stubborn way, by hope. Brandon’s jaw was square in the way of people who had taken too many hard looks at the horizon and decided one day to hold their own. He had a son—Braxton—with wide, unguarded eyes. Braxton’s fingers loved to touch things the way curiosity does—softly, as if testing tempers and textures. Brandon worked odd jobs in a neighboring town when he could, drove a used truck with pride, and held plans so private he sometimes seemed embarrassed by them.

“You gonna film us all day?” Brandon asked Mark without bitterness, only a practical curiosity.

Mark smiled. “Only what you’re willing to share.”

“Funny,” Brandon said. “People always are.”

Mark brought more than a camera. He brought a promise: better care, brighter prospects. To many who watched his videos later, his work would seem like an act of salvation—GoFundMe pages filled, nearly sixty thousand dollars raised, a new roof nailed in place, a refrigerator that hummed like a small miracle. But up close, the story stuttered. The Whitakers, for all their hardship, were also people schooled in a certain kind of resourcefulness. They could name which of the donors had called to ask about the roof, which one had sent turkey sausages, who had insisted on coming to help lift plywood but then stood in the yard and talked most of the day. The donation meant warmth. It also meant attention. And attention had a way of warping the edges of truth.

The first problem appeared, as many problems do, in the small and humiliating details. Mark read a message from a woman in Ohio—she wanted to send flowers because she’d heard that Larry had died. Larry was, depending on which Whitaker you asked, the brother who wandered the ridges, the man who sometimes belonged and sometimes did not. The Whitakers accepted offerings as a bad harvest accepted rain: gratefully and as if it were owed.

“It’s okay,” Lorraine said when Mark handed her the phone. She sounded oddly steady. “He’s—”

“Dead?” Mark asked, too blunt.

Lorraine’s shoulders flexed. “He’s gone,” she said. “To the other place.”

Mark believed her. The world had taught him to accept stories that matched his lens, particularly when the story could be monetized into empathy. The funeral never happened. Larry still walked the hills on certain days, though he kept his distance from the road. When Mark learned the truth, he felt hollowed: both used and used. He confronted the Whitakers with a mix of anger and apology that read more like chagrin than righteousness.

“We gave because we wanted to help,” one donor wrote on the page. “And they lied.”

That echoed in Mark’s calls and in the town’s coffee-shop murmurs. The Whitakers had been complicated before a camera rolled; the camera only made their complications a public commodity.

But this was the surface. The deeper story threaded through years of isolation, lack of access to healthcare, and the stubborn traditions of a place that saw marriage as a practical solution more often than a romantic one. The biology of it—how recessive genes find each other like lonely returning travelers—was clinical and cold. It explained some of the lines you could see on faces, the way some voices muttered and some minds worked like weathered machines with missing cogs. It did not explain the tenderness Brandon showed his boy or the way Lorraine methodically coaxed a stray dog back into the yard. It did not explain that Rey could hum a strange lullaby that sounded, if you allowed it, like an apology.

The real tension arrived the month Braxton turned six. Brandon had been saving his tips and odd checks to send Braxton to a public school in the county town, a place with a bus route and a classroom big enough for curiosity to uncurl. It was the small rebellion of a man who wanted the next generation to have options he didn’t. The school required forms, immunizations certificates, and signatures. For the first time, Brandon found himself at the mercy of institutions that spoke a bureaucratic language he had only half learned.

“You need a birth certificate,” said the clerk, a woman with a voice so habitual it could be lazy. “And immunizations.”

Brandon’s jaw set. He had a birth certificate, he said—somewhere. He had a stack of papers tethered to his truck like a swaying banner: receipts for a used lawnmower, the title for the truck, an old hospital bracelet. But the birth certificate had been lost in moves and fires years ago. He could not easily produce the neat proof the clerk demanded.

“You need to go to the county office,” she said. “They’re open Tuesday through Friday.”

Brandon left with the thin paper form and a promise to come back. He got the immunizations themselves on a clinic day three towns over, standing in a line of travelers as if the bureaucracy was a train they were all waiting to board. The nurse who administered Braxton’s shot was gentle, and the boy didn’t flinch. He was small for his age but bright, his questions pouring out of him like a spring.

When Brandon told Lorraine about the school, she was careful. She’d seen the way schooling had broken other families open—returned them to a world that judged and also protected. She rubbed Braxton’s head with the knuckles of someone who thought in chores and prayers.

“You sure?” she asked Brandon, voice low.

“I owe him a chance,” Brandon said. “He’s not a copy of what came before.”

That was the heart of it: the Whitakers might be a knot, but knots can be untied. Or, at the very least, woven differently.

Hope drew attention. Hope also drew predators. Mark returned to Odd with more cameras and a higher subscriber count. His videos streamed the family in slices—repairing the roof, a Thanksgiving where they sat like a clumsy truce around a borrowed table, Braxton’s first steps toward school. Comments rolled in with goodwill and with a nastier undertow: people speculating, pronouncing, treating diagnosis like Sunday conversation. The town watched with a mixture of pride and embarrassment. Some neighbors felt grateful that someone had finally brought help. Others muttered that the Whitakers had once again invited strangers to a table they could not afford to feed.

And outside help brought other hands—volunteers who wanted to teach cooking classes, mentors who wanted to give Braxton tutoring, doctors who offered screenings on a Saturday. For the first time, Rey went to see a neurologist in the county. He disliked the fluorescent lights and the neatness of the clinic but sat with an expression that mixed suspicion and something like relief when the doctor spoke in measured terms they could both understand.

“It’s not just one thing, Rey,” the doctor explained in a voice that refused to hurry. “Some conditions are genetic. There are ways we can help with behavior and speech. There are supports. You’re not alone.”

Rey’s grunt held a place where pride and gratitude locked horns. It came out like an answer that could not be bottled.

Progress is rarely linear. For every roof patched, there was a rumor revived. For every person who offered tutoring, there was someone else who wanted to cash a check into a headline. The donations had made tangible difference—but they had also made the Whitakers into a story that belonged to strangers and to a timeline of views. When the truth about Larry’s “funeral” surfaced, the donations tightened their chokehold on goodwill. People felt cheated. The Whitakers felt wounded.

Brandon was the hinge between the past and the possibility. He was also a man with a temper that had learned sharpness from many small losses. One afternoon, the county bus driver—an older man with a shrewd face who had once driven Brandon’s uncle to the coal tipple—said something about “the Whitaker circus.” The look on Brandon’s face went from contained to volcanic in a breath.

“You don’t know us,” Brandon said quietly, and the bus driver’s eyes lowered. For all the scorn around them, there were lines of loyalty too. People in Odd knew that if things came to blows, they would be the ones called to help. It’s a cramped economy of obligation.

The climax arrived like a night storm, sudden and implacable. Someone put up a video—uncredited and vicious—compiling the flashes of the Whitaker quirks into a montage and setting it to a music that wanted them to be monstrous. It trended in the small world of outrage. Comments rolled in that tried to laugh, to name, to condemn. Braxton saw the video on a phone at a volunteer’s trailer and asked why the people were laughing at Rey’s hundred-yard stare. Brandon’s rage was a contained animal. He reached out to Mark; Mark said he hadn’t made that video and that he was trying to push back.

The town’s defenses hardened. People came to the Whitaker porch in twos and threes to stand near the yard and watch the road, as if patrols of normalcy could keep tides of ridicule at bay. Volunteers who had taught cooking classes packed up their aprons with apologetic murmurs; donors withdrew their monthly pledges. The net that had been, in some ways, a lifeline now seemed a rope that could be pulled taut.

“You think they want to be famous?” Lorraine asked one night, voice raw. She was younger than her weathered face suggested and cried like someone who was tired of being the subject she had to defend.

Brandon put his hand on her shoulder. “No,” he said. “But they want to be seen for something besides what people figure.”

It was then that Mark made a choice that would define his story. He had the audience, the reach, and his editor had a thousand small pieces of footage that could be cut to whirl like a carnival. He could increase his clicks and his subscription numbers with outrage. Or he could tell the truth—messy, complicated, unprofitable and human.

Mark chose honesty.

He posted a long video—not a montage but a narrative. He spoke to the camera without spectacle. He apologized for the harm his lens had caused before he had properly understood. He showed a side of the Whitakers that made no tidy point—Lorraine, late at night, sorting medicine bottles; Rey, humming to a song he couldn’t name; Brandon teaching Braxton to change the oil on the old truck; a neighbor, Ms. Hobbins, bringing over soup; a county nurse explaining immunizations with patience. He refused sensationalism. He refused to become the narrator they could not live with. He left in the awkward moments: the lie about Larry’s funeral, the confusion between gratitude and exploitation, the ways the family had hurt people and been hurt in return. He let the Whitakers be both culpable and beautiful.

The reaction split the world in half. Some people unsubscribed in disgust, tired of nuance. Others flooded the comments with stories—of their own families who had been judged, of the small towns where daylight had not quite reached. Donations came back but different: smaller, steady, from people who wanted to build sustained support rather than one-off spectacle. A local clinic started a monthly outreach program. The school bus came to the Whitaker hollow on schedule. Braxton began to go to class every morning, with a backpack too big and a grin that could break stone.

Rey had a therapy plan. Lorraine started attending a support group at the county library. Timmy, though still wary of strangers, learned to sit in a corner of the classroom while Braxton read aloud—his barking reduced to a comic punctuation the kids in class found charming. Brandon took night courses at the community college across the ridge. He studied small-business management; he dreamed, quiet and steady, of owning a small repair shop where hands and knowledge replaced some of the family’s economic precarity.

But the mountains are not tidy. Old patterns ripple. Weddings, funerals, and everyday comforts tend to revert a family to its old muscles. The Whitakers had to be vigilant and intentional. They learned to name the things they wanted to change, and then to do the painstaking work of walking away from the old scripts. It was Brandon who had to show the family what change looked like—turning down a cousin’s marriage proposal that would have been convenient in traditional terms, insisting that Braxton’s future be decided by tests and choices rather than by the loop of blood. Those conversations were not painless. They dug at loyalty, at superstition, at practical fear. But the family had a new defense: knowledge, resources, a slow, awkward public respect.

Times of crisis teach you who you are, and times of quiet teach you what you want to become. For the Whitakers, quiet came in small acts repeated: Braxton coming home with homework that Lorraine helped him with even when the sentences felt like foreign speech to her; Rey working with a speech therapist to shape sounds into words; Brandon waking up before dawn to head to a town three miles away for a class and a shift at the repair shop where he hoped to apprentice.

One spring day—bright, unlikely, clean—the town of Odd gathered in a small clearance near the post office. They built a small playground with patched lumber and a swing that squeaked like a memory. Volunteers hammered smiles under the watchful eyes of neighbors who did not wholly trust change but tolerated it as one might tolerate a risky medicine. Braxton ran in a way that made his smile contagious; Lorraine watched from the edge like someone who had learned to breathe outside a crumbling wall. Rey sat on the swing with a neighbor’s help and pushed with a gentle certainty that looked like joy.

At a small table under a borrowed canopy, Mark caught Brandon and shook his hand. “You did this,” he said, earnest in the way of a man who had learned humility the hard way. “You did the hard thing, Brandon.”

Brandon’s laugh was small, relieved. “We did it. All of us.”

Someone in line—a woman who taught kindergarten—leaned over and said, “He’s come a long way. So have you.”

The future, in Odd, was not a bright ribbon stretching forever. There were debts to pay and prejudices to break, illnesses to manage and histories to apologize for. The mountains did not forget. But the Whitakers had begun to push their lineage in a new direction. They studied what genetics meant not as a condemning label but as something to be managed and understood. They learned to say no to easy marriages and to say yes to schooling. They asked for help and then learned how to make it sustainable.

If you asked Lorraine years later what she remembered most about that period—the roof or the refrigerator or the barking montages or the theft of the narrative—she would look at you like someone weighing a will.

“People are complicated,” she would say. “We are complicated. But the thing that stayed was that people showed up—not to judge, but to stay. That changed it.”

Braxton grew taller each season. He kept his curiosity and added patience. He loved diagrams, especially the ones about engines. His teacher said he had a knack for taking something that seemed broken and understanding how it fit back together. Brandon, working late nights and early mornings, found work steady enough to begin thinking about a tiny shop near the county road. He dreamt of hiring a kid from town who needed a job, of giving the next generation not a pity check but an offer of work and dignity.

Rey learned to speak more than a grunt. He learned to name his needs and to ask for a person’s name before answering. Timmy grew less inclined to bark at strangers. The Whitaker house kept its sag, but the inside smelled sometimes of coffee and possibility instead of only dust. Old photos were reframed; new photos were added—a class picture with Braxton in the center holding an A in pen, a photo of Brandon handing a wrench to a boy from the next hollow, a picture of Lorraine teaching a reading group at the library.

Most of Odd returned to its rhythms; the road to the county filled again with the sounds of a town that had less to prove. But the Whitakers were no longer merely a curiosity. They were a family that had been seen, that had accepted some help, that had failed and then repented, that had been exploited and then reclaimed their narrative. They were also, quietly, survivors who chose to be more than the inheritance of mistake.

There were no speeches, no final triumphs dramatized for a camera. Life settled into incremental adjustments: paperwork taken care of, therapy sessions attended, nights when the coal was less likely to leak damp into the bedroom, small celebrations for birthdays where pies were passed and hands clasped. There was grace in the small things, a sense that dignity could be rebuilt, not given by strangers but forged through stubbornness and aid stitched with respect.

On the porch where the Whitaker kids had once sat like a static scene, a new sound began to settle: the laughter of children mixing with the wind. One evening, as twilight fretted the ridges into softer shades, Brandon sat with Braxton on his knees and watched the first stars pierce the sky.

“You know what I think?” Braxton said, voice round and earnest.

“What’s that?”

“That maybe places aren’t only what they were. Maybe they’re what we teach them to be.”

Brandon felt his throat tighten. “Maybe,” he said. “That’s the work.”

Across the hollows, the mountain held old ways like a memory that had not yet learned to let go. In the Whitaker yard, though, hands planted a small garden. Lorraine tended it as if the plants were a promise. Rey brought water in a careful rhythm. Timmy guarded the gate with a half-bark that sounded almost proud. They were not cured of everything—they bore the marks of their history like weather on skin—but they were learning the less glamorous art of repair: to show up, to insist on help, to refuse easy lies, and to teach a boy to think differently.

The world beyond Odd would still watch and judge and misunderstand. But inside that little yard, the Whitakers began to teach one another what it meant to live differently: not to erase the past but to work with it and toward something steadier. They had been famous once for all the wrong reasons. They were teaching, slowly and insistently, how to be known instead for the way they learned to be kind to themselves.

On clear nights, a violinist from town—an old woman who had once played at funerals and weddings—would walk down the lane and sit on the Whitaker porch. She’d pull a song from her case and play something gentle and old. Rey would try to hum along. Lorraine would press a hand to her chest. Brandon and Braxton would listen and sometimes sing a line.

“Music remembers for us,” the violinist said once, when someone asked why she kept returning. “It remembers the things we need to keep.”

It was true. The Whitakers were learning what to keep and what to let go. The knot of their lineage remained, but it was no longer all that defined them. They were, in the end, a family like any other: full of mistakes, full of love, and capable of change if enough hands reached out at the right time—and if those hands kept reaching, not to take, but to steady.

News

End of content

No more pages to load