And then things began to happen.

At first it seemed like the sort of misfortunes that visit all plantations in August. A lantern would crash as if someone had tripped, though no one was near it. Tools would go missing, only to be found later in the clump of a field where no one had been working. A horse that once would shoulder a gig into the road refused to pass a certain bend as if a memory of something terrible lived at the roots of the willow trees there. These were the kinds of irritations one could blame on weather, rust, or carelessness—until the eyes grew strange.

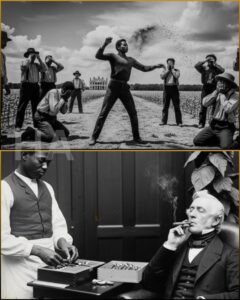

The first overseer to lose his sight was a man named Harris, who kept a temper in his throat like a snake in a pocket and could never quite hide the whips that hung off him like accessories. He was the sort of man who believed vision and authority were twins; if one faltered, the other fell apart. One humid midday, he strode across the cotton maw, searching for tools he claimed had been misplaced. Sweat clung to his shirt, and the sun leaned heavy on his brow. He began to rub his eyes at first, as if something had blown into them. His breathing fluttered like a bird trapped in a jar.

“They been playing games,” he muttered. “Someone done something.”

A boy—Ellis—moved to bring water, but Harris, frantic, tossed him away as if a cloth had been thrown upon his face. Ellis had only stepped in with the colonied bucket. He had seen no trick. Harris’s words turned frantic. The world dimmed around him like a lid descending, and he reached for the post, for a bench, for any shape he recognized. He called out a name once—a single syllable that matched the sound of Nate’s name—and then he was gone into darkness as if a curtain had been dropped over his sight.

The plantation doctor, Dr. Penn, a man who wore his respectability the way men wear embroidered coats, came and examined him. There were no wounds, no infection, no ribbon of scar that would explain this sudden blindness. The eyes were clear and uninjured, and yet they stubbornly refused to work. Harris could only say, “There was a flash.” He could only say that something like a lamp had been borne toward his face, but sharper, wrong, and that after it there was darkness. When he tried to explain, his voice sounded like a man telling a dream.

People spoke then of curses and spirits and revenge. The owner shook his head with disbelief, but his jaw had softened. He ordered that the overseer be sent down the road to a town doctor with more gadgets and less superstition. It was an admission of insufficiency most owners could not bear to make.

But it did not end with Harris. The second, the third, a string of overseers found their sight fail them in the same haunting way: a sudden bright flare and then nothing. Each could recall nothing but a streak of light, coming out of nowhere like a piece of sunlight with the teeth filed down. And each of them had seen Nate nearby in the moment before the brightness. The pattern grew like lichen.

At night, the cabins hummed with soft conversations. The enslaved people—women and men who had learned to measure every word—exchanged observations beneath quilts and under the breath of fans. They spoke of the way Nate would stand on the margins of the field as if counting steps. Of the way he would leave at the end of the day with his hands empty and come back to the smokehouse at midnight with pockets full of small things for which he had no use: glass shards polished to jeweler-sheen, a bent piece of tin with an edge like a scab, a splintered mirror from a discarded comb. He would rub them until they gleamed, fitting fragments together like the pages of a book only he could read.

“They say he got some education ‘fore,” Old May said once, but no one could remember exactly where she had said it. “Men went to the cities sometimes, or trained by a crooked master. Does not matter how. He got know-how.”

Nate, for his part, did not boast. He only did. In the quietness of the smokehouse, where the air smelled of cured meat and old wood, he built things that had no name. A lens from a cracked watch he held to a sliver of glass; an arc of light crawled across wood and bloomed like a small sun. He watched how the light behaved—how its edge sharpened, how a beam could be tightened by a concave surface, how one thin thread of sun could be made to feel like a blade if aimed at the wrong place: the wet center of an eye, the window of vision.

It was a small, precise science. He liked precision.

When men began to speculate openly in the fields about who might be accountable, fear strangled the talk. They looked at Nate with new eyes, equal parts suspicion and awe. He had not raised a hand in anger. He had not spoken a word of rebellion. He had not plotted in the cabins like some villain from a play. He had only learned the landscape’s littlest languages.

The overseers could not abide being made vulnerable in such a way, so their answers turned again to cruelty. They punished that which they could punish: anyone who looked away at the wrong second, anyone whose finger smelled like stolen tobacco, any child who lingered too long near a tool chest. They lashed small men for imagined offenses and pushed the fear down onto shoulders already bowed. Violence grew in the attempt to claw back certainty, but the violence only made the plantation more brittle. Each passing day the overseers’ confidence eroded; panic crept into the steadiness of their steps. The tricks, whether spiritual or made of glass and geometry, continued.

He was methodical, Nate. He counted steps and listened to breathing. He knew where the light would flash at midday off the corner of a particular plow because he had spent nights measuring angles by moonlight. He knew which man would be leaning when he checked the cotton because he had watched habit like a script: every man has a tell, a slight bend of the torso, a soft turn of the chin. He timed, always, to a breath. He used objects that existed on the plantation already—the curved shine of a tin pan, a sliver of broken lantern glass, the hollow of a spoon polished by generations—to focus a beam. It required no great invention, only small, deliberate understanding and the willingness to wait.

Patience, Nate believed, was a weapon the overseers never expected. They had power for swift violence; they lacked the temperament for time and nuance. If you could measure a second and aim a reflection into it, you could change the shape of a day without a shout or a fight.

Over the months, the tally climbed. By the time the tenth overseer went dark for reasons no doctor could tell, the rumor had carved itself into the bones of the place. Men who once strutted with authority shuffled by the fields as if the ground might collapse underfoot. They tied cloth around their eyes as superstition demanded and carried open lanterns in noon sun as if light were the enemy. The plantation owner tried to cover the story with official silence; he sent round men with quiet tongues to the town to fetch a surgeon, and he suggested, with a sick man’s cadence, that blindness could spring from bad water, pulped poison, or even God’s displeasure. But those who had been touched by the darkness knew better. Each of the blinded said the same thing in the end: a flash. A pinpoint of terrible light that settled into their eyes like a coal.

And still Nate never looked like a triumphant man. He went about his tasks with the same calmness as before, as if doing a job without emotion. His silence was the sort of silence that carried meaning: he would be watched, observed, and then nothing. He refused to play into pride. If his end game had been only spectacle, it would have been different. He had strategy. He had purpose.

The people in the cabins began to move with a different kind of steadiness. They watched the overseers’ reactions like a chorus watching a single actor. They did not celebrate the fall of a man. They were not cruel. There was no revelry in the loss of sight for any human. They only measured relief; the overseers who once delighted in power now lived with the tremor of vulnerability. When an overseer leaned too close to a woman at night, she could shrug him off and not worry for the same retribution. They could light fires in the yard and sing without having the whip break the song. The small acts of dignity multiplied, not as a triumph of cruelty but as a soft undoing of fear.

Yet for all that, the hunt tightened. The owner could not allow such disorder. Reputation mattered, and the ledger must balance. Men were raised from neighboring plantations and urged to ride and search. Men with dogs came and tramped the furrows so loudly that birds fled the branches and never returned for days. Overseers walked two by two and three by three, their backs pinned like soldiers. They questioned the women, searched the children, pried under thatch and bed, broke loose boards to show a thoroughness that read as desperation. Nothing found the maker of the trick.

It comforted Nate that he had left no trace. His tools—if you could call them that—were the kind that the ground took for itself. He would take a shard, use it, then drop it into a place where the mud would swallow it, and time would make it indistinguishable from the dirt. The manhunt proved little more than theater and humiliation for those who had thought themselves invulnerable. Each new failure made the overseers more ruthless. Each new failure made the man they chased less human and more a thought, a ghost they could not cage.

The culminating week came with a heat that felt like a slap. The sun sat like a coin against the sky, and tension coiled through the cotton rows like a wire. The owner, Master Caldwell, called a meeting under the great oak that shaded the yard—a spectacle meant to show the community that he still held authority, that he could gather men under the same benediction of order. It was a show: town merchants, a preacher who smelled of beeswax, and errant gentlemen came. Men who had been spared the darker night shadows came to witness a demonstration of control.

Nate walked among them that morning, shoulders low, hands as steady as ever. He had been born at the edge of an earlier life and had learned to be invisible in its glare. He found himself watching the light as systems of the day collided: the sun slanted, a cloud wandered like a lazy ship, the barn’s tin roof flashed. A meeting like that was an open prize: many men, heads down, hands distracted, faces turned in directions that were predisposed to habit. Nate noted who would lift his hat to wipe his forehead, who would lean to pick at a splinter on the rail, who would gaze specifically toward where the town gossip stood to make a joke. He measured breaths like someone listening for a dropped coin. He had rehearsed this in the smokehouse; he had practiced his aims in stolen moments when the moon had been a thin eyelid.

On the day of the meeting, Master Caldwell began with pomp and a voice like thunder in a glass. He stood to show the field that the rules remained. But the audience was scattered and fractured: merchants with faces pale under their beards, overseers with a tremor at their wrists, and men from the town who watched the spectacle with the same quiet anxiety as if it might be contagious. Nate moved near the back, a silhouette that might as well have been a shadow.

It happened in pieces, so quickly that only later would people stitch it to a whole. A man in the third row, an overseer named Lyle, blinked as if a mote had leapt into his eye. A flash. He jumped, cursed, and then laid a hand to his sight and could not find it. The world shrank to cotton and rail and some indeterminate dark. He stumbled, and the circle of men around him opened like a mouth. Others began to call for water, for a doctor, for a preacher. The preacher crossed himself, muttered about the devil. The town merchants began to murmur.

Then another, then another. First two, then three, then a trickle that turned to a tide. The light in the sky did not change. The cloud that drifted by was ordinary. But the beam—thin as a needle—cut through like a surgeon’s whisper. Nineteen men fell in those hours into sudden blindness. Some fell with palms splayed to catch a wall. Some grasped at hats like a child trying to wring from them the sun. The yard turned into a place of hands and voices and the terrible hush of a world gone opaque.

Panic spread like a stain through an unsealed bottle. The owner’s face paled as men crashed into one another, their eyes useless. Dr. Penn moved among them with instruments small enough to belong to a different age, like trinkets that symbolized knowledge but could not solve the fundamental impossibility on display. His face knotted into something like fear. The preacher prayed loud enough to spill his words into the field, but prayer would not stitch back vision.

From the cabins, Old May and the other women watched. They did not laugh. The world had tilted into sorrow. Nineteen overseers—men who had been the wind that made their lives tremble—were now men who could not find the horizon. Some of those blinded would not walk the same way again; their steps would be stooped with the need to feel the world at their hands.

No one who stood beneath the oak that day saw Nate do anything other than stand in his place and be seen. He blinked as if a lint had invaded his eye. He did not run. He did not shout. In the crowd’s terror, in the blur of men, in the hammering voices, he looked almost ridiculous in his calmness. But then a whisper ran through the field like a knife: someone had seen him lift something—half a sliver of glass—catching the sun’s angle for a heartbeat, and the light had leapt like a living thing from it into the faces of the men who had been facing the wrong way.

Nate’s aim was impeccable. His timing was surgical. He had thought, for many months, about where a single flash would render a man helpless and how that helplessness could change the rhythm of control on the plantation. He had known that some would be permanently harmed; he had also known that no other avenue existed. He had also known that the consequences would be terrible. This was not a reckless boy’s prank. It was the quiet arithmetic of what the world owed and what it would tolerate.

When the first voices in the field began to name him, he did not run. That was the strangest thing. A hundred hands pointed, and men who had entered the world with whips now stumbled forward like men who could not see their own hands. Nate stood where he was, shoulders squared, the sun catching the edge of his cheek like a coin.

“You!” Master Caldwell shouted, though his voice, for all its thunder, trembled. “You—come here.”

No one moved. It was always the same in the end: the ones who had been used to striking were now powerless. The owner wanted murder, wanted a public ripping of skin. Men called for a rope, for the dogs, for the hangman’s noose the world had long ago prepared. When two burly men lurched toward Nate, he did the unexpected. He did not defend himself with strength. He did not plead. He reached with both hands—gentle, sure—and he took the hat from a blind overseer’s head whose fingers groped for the crown like a man lost in a crowd. He placed the hat carefully on the overseer’s head, the gesture of someone who knew how to comfort without words.

The sightless man gave a small sound, like the hush of a child falling asleep. Nate’s hands were as soft as the water he once used to wash a face. That touch, that strange mercy, was what shook the owner most. The yard could not abide that the man they had criminalized would offer kindness in a scene of violence. The onlookers were avaricious for spectacle—if not blood, then at least the crushing display of order—but Nate refused to feed them.

It would have ended with a rope if not for the thing that saved him: the very fear he had seeded. The owner and men feared the unknown so much that they persuaded themselves to choose containment over blood. If they hanged the wrong man, what would stop them from continuing to lose the balance? If the trick was indeed of light, and if the owner killed him, someone else might pick up that glass and finish the job. So they did the other thing that owners sometimes did when they were small: they traded. They arranged to send him away instead of killing him, because his absence could be marked in a ledger, explained in letters, and sterilized into history.

Nate was sold to a trader from the coast, transported downriver with a ledger and a clean note that said nothing of experiments and everything of commerce. He left Willow Hollow not under rope but under the watchful relief of men who believed they had taken back the world by moving a piece on the board. The women and men in their cabins watched him go with the same quietness as a storm departing: they did not cheer, they did not weep openly. They had learned something deeper—how to keep a secret like a seed for spring.

The trader took him east, toward a town with warehouses stacked like ribs. He took with him not only a man but a story with a thin, sharp edge: Nate was a craftsman who worked with glass and could make things from nothing. If merchants heard such a tale, they might pay more. That was the calculus. But the trader’s ledger would not account for what Nate had learned beneath the smokehouse and the oak. He carried knowledge like a living thing, a set of skills that could bend a ray and turn a wink into a wound. He also carried the memory of the eyes he had marked. He had not wanted to hurt; he had wanted to make power reconsider itself.

In the town by the port, Nate found himself in the company of men who saw him as a curious hand to be used. There he watched other faces: sailors with salt in their hair who learned quickly how to trust the hands they could not own, dockworkers who bartered with their own stories, and freed men who had crossed from the North and spoke of places where names were not owned and where a person’s skill could be currency that the ledger could not count. To some, Nate explained nothing. To others, he offered the smallest of lessons about angles and light and the way a shard will hold the sun like a captive. He taught children in the evenings how to use a sliver to make a compass of shadow. He showed them how to read a glint like reading a friend’s expression.

He made no attempt to return to Willow Hollow. He had known, in the hours after the long blinding, that something fundamental had shifted. The owner’s world was cracked, and even if the owner stamped a seal on it, the seam would not close. The women’s nights grew softer. The men who had once stomped about with whips learned to move in ways that sometimes made room for human voices. This was not emancipation. It was a fissure. But fissures widen.

Years came with the thunder that none could foresee; the country would burn in a war neither the owner nor the trader had planned. Masters would worry less about reputations when cannon smoke began to choke the air and men were called to a cause that asked for more than ledgers. Nate’s name—gone from the owner’s ledger and remembered in a few drawers of gossip—traveled like an ember on the mouths of those who had felt his soft hand on a crown.

War unraveled things and remade many. Some overseers died in foreign fields; some returned blinded by different horrors. Willow Hollow itself changed hands when the old owner fell into debt and lost his property to a man who used the land to raise corn instead of cotton. The cabins that had been crowded with secret stories saw a subtle easing. The law would not grant freedom in a moment; the world had to burn and be stitched anew. But embers of what Nate had made—pride distributed, fear rebalanced—persisted as a small justice.

Nate himself lived into a later life that the ledger could not predict. He learned how to read a scrap of paper, taught to him by a schoolmaster who had been kind when kindness was not profitable. He married a woman named Ruth, who made quilts the color of late sunlight and who always smoothed the map of his face with her small, certain hands. They had a daughter, a strong-headed child who would grow up calling the towns by different names, who would ask her father once why he had done what he did.

“For the things you could not steal back,” Nate said, and his voice was the kind men use when the words are heavy with distance. “For the chance that a man who hits will be touched by being hit back in a way that won’t kill. We have to use what we know. We have to bend the light sometimes to make the powerful see what it feels like to be blinded by what they do.”

“How can that be good?” she asked, young and impatient, as children are. “Blinding a man…That’s cruel. Isn’t there another way?”

“You don’t see the first time,” he said. “You don’t see how many times you ask for mercy and get none. Sometimes you have to make a wound speak loud enough to be heard.”

The daughter grew into a woman who would speak in town meetings and who would not be cowed by men whose names were carved into docks. She would tell the story—never with the cruelty but with the truth—that a man once chose to counter violence with something that did not take life but did make men reckon with their own fragility. In her telling, Nate was not a hero born of song; he was a man who had done what he had to do, and who had then lived to teach small children how to polish a sliver of glass into a sun.

That is not to say the world smoothed into a neat, moral line. People suffered, and some of the overseers—the ones who had lost their sight—lived lives of bitterness. They cursed the name Nate and traced his silhouette into new nightmares. Some tried to find him in the post-war towns. Some punched walls and drank themselves into stupor. Hurtmen hurt. But others were undone by their own blindness and turned their hands to gentler labor, humbling acts that the land may have counted as atonement. War does strange things to guilt.

Toward the end of his life, which came like a tired saint’s, Nate would sit on a porch not far from the river where he had once learned the geometry of reflection. He would take in the fields with his daughter’s children running like the noise of a kind of music. He would tell the small ones stories that were careful and half in code, about how sharp the world can be and how dangerous a small beam of sun can be if you do not know where to point it. He would show them how to hold a sliver and how to keep a secret without letting it grow into a cruelty.

“Remember,” he said once, to a boy whose eyes were quick as minnows. “Tools can change things, but so can kindness. You can make a man fall, but you can also help him up afterwards. If you choose to harm, choose to learn to heal after.”

People asked him later—for the rest of his life and in the years after that—what had finally become of those nineteen overseers and of Master Caldwell. Some of them buried themselves in grain and silence. Others left. Master Caldwell died without much fanfare, his debts and reputation reduced to footnotes. The ledger that once counted men like Nate merely transformed. In small towns, these stories sprouted up like weeds and then were cut down. Memory is a strange garden.

It was not a triumphant ending. It was not a cinematic revenge. It was a life like a river’s course—bent by obstructions, finding ways around stones, and sometimes pooling into a place of quiet. Nate’s method had been malicious and protective, a double-edged thing that can grow in anyone whose world offers fewer choices than bone. He had not set out to be myth. He had wanted simply to tilt a power that had settled heavy upon others. In doing so, he had changed the shape of their days. He had taught the land to look back.

Years after the last overseer who remembered his name passed away, children on the same plantations would tell the story differently. Some would say he had been a conjuror who held the sun in the hollow of his hands; others would say he had been a man who made cruelty stumble. Some would reduce it to a moral about what happens when the powerful forget the fragile parts of the world—their own eyes, their children, the tenderness that should hold them steady. To each listener, the story would shape itself to what they needed to know: that justice sometimes comes like light, precise and unable to be held, or that courage can be made of small things: a shard of mirror, a moment’s patience, a single man who will not raise his hands to celebrate a beating.

In the end, Nate’s life was a study in modesty and consequence. He paid neither with chains nor with a triumphant death. Instead he gained a life of ordinary kindness: a wife who sewed the lines of his days into comfortable quilts, children who called him by a name he chose for himself, and a town that would sometimes nod in recognition when his face passed. He died with hands that had done both harm and solace.

The grave they dug for him was simple, and someone—perhaps Old May, if she lived that long—left a small mirror at the headstone, not to celebrate what he had done but to warn. When people walked by, the sun would catch upon it and throw a shard of light across the grass. Children ran through that glint and learned how sunlight could cut like a ripple. Farmers passing later might think it superstition and move on. But some would pause, look at the flash, and remember that there are tools that can mar as well as mend. They would remember to look at their own hands.

Storytellers later would alter details, as storytellers do. Some would call him “the slave who blinded overseers,” a title cruelly clean. Others would make him into a saint of sorts. Yet those who had known him—the ones who had watched the slow change of men and the soft loosening of fear in the cabins—would say with voices careful and steady that he did what he did not to be cruel but to break a rhythm of cruelty. They understood that what he had chosen remained a dangerous thing. It was not without moral costs. But it had made room for a small mercy: days when the whip fell less often, songs that returned to yards, and the knowledge that sometimes, to stop a blow, you must find a way to make the blow themselves reckon with its own power.

Nate would be the kind of name that sits uneasy on a tongue. It will never fit into a ledger cleanly, because the ledger was never meant for that. His story will live somewhere between the measured mathematics of light and the soft, messy calculus of mercy. It will be told in the hush of a porch, in the careful way a child learns to handle glass, and in the way older men sometimes touch their faces and remember how fragile sight is. The trick he used was impossible to most; to him, it was a tool learned from the things the world had thrown away.

The final thought that hovered like a feather over his life was not of pride. It was of responsibility. A man who changes the balance—even a little—owes himself to hold the balance gently afterward. Nate learned to do that in his later days. He mended wounds he had helped open. He taught others how to use what nature affords without wanton cruelty. He refused, in his last years, to let his craft become legend without caution.

If you go now to the dirt road that once led to Willow Hollow, you will find that the fields have names and the trees have grown, and the land has forgotten some of what once lived there. You may even find a small, dull glint in the grass beneath an old oak—a remnant of a thing that once held sunlight like a secret. If you pause and let the sun catch that glint, you might think you see, for an instant, the shadow of a man bending over a sliver of glass and thinking not of revenge but of balance, not of cruelty but of the quiet, terrible measures that sometimes make room for mercy.

They said he blinded nineteen men with a trick that no one expected. It is true, in the sense that history will permit truth to exist. But truth is never simple. It tastes of ash and honey both. Nate’s trick did harm; it also loosened a pattern of fear. It made people on both sides of that field confront what they were willing to do to keep their power. In the end, that reckoning—uneven, messy, human—was the closest thing he could offer to justice in a world that had very little of it.

And that was perhaps all any one man might do: make a small change and then spend the rest of his days trying to stitch it into something that mended rather than broke.

News

End of content

No more pages to load