Whitfield closed the paper to steady his fingers. “Mrs. Thornton,” he said, and the courtroom quietened around the simple way his voice bore the weight of procedure, “your husband came to my office six weeks ago and dictated this will personally. He insisted it be read exactly as written.”

“Six weeks?” Margaret’s laugh was dry and furious. “He sat at our table six weeks ago? He ate my bread, planned our affairs, and he did not tell me?” Her eyes moved like a gambler’s hand across cards, searching for some misdeal. “Who is this Eliza Marie? Who is she?”

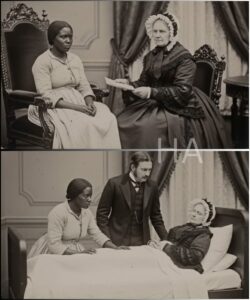

A figure in a plain grey dress stepped into the doorway, small against the heavy frame of the parlor but impossible to ignore. She came forward with the careful smoothness of someone who had long learned the art of being seen but not named. Her hair was pulled back; her skin had the mellow hue of old oak. Her eyes—amber and steady—saw everything at once.

“I’m right here,” she said.

A name had been spoken aloud that earlier had existed only as a whisper. A woman who had been property yesterday was, by the ink of a paper and the will of a man, free today. For Eliza Marie, the world had altered under her feet from one day to the next; for Margaret, the world she had arranged to be safe and readable had been rendered illegible.

“She told me three days before he died,” Eliza said, simply—an unadorned fact that felt like an accusation. Margaret’s hands trembled. “Three days and not a word to me? Not a word to your wife?”

“You never gave me anything,” Eliza answered, calm and clinical as a surgeon. “You gave him permission to own another life under your roof. You fed me, clothed me. You called me a servant and expected nothing more than obedience. I owed you nothing but the labor that was taken from me.”

The parlor held a long, terrible silence. For eleven years Eliza had lived in the flickering spaces behind the house—the kitchen’s hum and the ledger’s hush—raising three children who had the Thornton nose and eyes but no name in law. She had kept accounts, supervised the household, and watched the pattern of scarcity and indulgence that made up plantation life. She had also learned. Literacy, once given in kindness by a previous owner’s wife, had made her measure the books and understand the margins where her husband’s broken promises hid.

So the will set the house on fire with its quiet paper flame. It would burn and consume for years.

The legal papers that Robert Thornton had left were clever; he had anticipated indignation and law. Whitfield had admonished him against the structure—some of his colleagues had even threatened public scandal—but Robert had been precise. He had written a letter to be opened should the will be contested, a letter that would later read like a man trying to justify himself to the last possible judge: the man before the grave.

“I stole eleven years of her life,” he had written. “I stole my children’s right to be free. This will is not charity. It is restitution, inadequate though it may be.”

That confession was the first brick in the battlements Thomas Thornton raised on behalf of his family. He filed a petition a week after the will reading. He would argue every indignity, every legal chink that might undermine his brother’s late conscience: unsound mind, undue influence, statutes that tied the hands of freed persons. He would do so with a practiced cruelty, because he knew what he was defending—an entire order of things that commodified human beings with the gravity of law.

The county courthouse was full on the first morning of the hearing. Natchez was a town that loved to see its own hypocrisies made matter-of-fact upon the bench. Thomas opened with a speech polished to moral outrage, his voice iron and shaped: a white man’s claim for the protection of his class. Eliza sat to the left with Whitfield, plain as a tombstone. Margaret sat to the right, her black silk feathered with society’s sympathies. The twelve men of the jury sat like a carved chorus of the old world.

The courtroom became a theater for the old scripts. Margaret performed suffering with a skill bred of necessity. She talked about propriety, about her role as a wife and the wrong of a servant presumptuous enough to be loved. Whitfield’s cross-examination chipped the performance. “You did not leave?” he asked, as if the question mattered less of scandal than of choice. Her answer—“where would I have gone?”—was both a plea and confession; it admitted the economics of marriage as much as it denied an inner truth.

Other witnesses spoke, some to Eliza’s credit, others to her damnation. Servants who had worked at Belmont testified to her fairness, to the way she protected fragile families from worse punishments. Aunt Ruth, who had cooked sour cakes and mended worn shirts for thirty years, looked Thomas Thornton in the face and said what no lawyer ought to ask: “How’s a woman who’s owned supposed to manipulate a man who owns all things? He came to her door because he wanted to. That ain’t manipulation.”

If anything turned the temperature of the trial, it was Whitfield’s calm reading of the letters Robert had written. They laid out, open and raw, the man’s admission: that he had been a coward, that he had loved one he had no right to love, and that the only currency he had to offer was the thing that had sustained his family’s comfort for decades—property.

Judge Hyram Foster listened to both sides with the fatigue of someone who knew his ruling would be less law than social arithmetic. He would come away from that bench with a decision not clean, but trying to be honest within an unjust architecture.

When he issued his opinion a month later, the courtroom quivered with anticipatory violence. He found in Robert’s favor as to his mental soundness and the absence of undue influence. It would have been a simple probate if not for a single, terrible limitation: the law of Mississippi had no appetite for a freed black woman to rule a plantation as a white man had—particularly if that plantation included enslaved workers. The judge could not render a declaration that would undress an entire social code. He could, however, attempt compromise.

He awarded Eliza freedom, custody of her three children, eight hundred acres known as the North Tract, and fifty thousand dollars in trust—administered by a court-appointed guardian—and he restricted her from owning enslaved labor. The remaining lands and holdings would remain with Margaret and the legitimate heirs, he said, with the rest of the estate distributed under standard inheritance law. The enslaved workers, he decreed with the cold impartiality of law, would be divided between estates or sold.

Relief and loss jostled at once in Eliza’s chest. She had won, at immense cost, a legal recognition of personhood. Her children were free in law, and in those two small things a future lived at all might bloom. But the judge’s ruling also confirmed the unbending cruelty of the system: she could not save others; families would be split as usual; the men who had bred their wealth on the bodies of people would keep most of the economic power. It was neither victory nor defeat. It was a place where justice had been cut to fit the machinery of a society unwilling to reconfigure itself.

In the months that followed, Natchez coagulated into camps. Merchants refused to serve Eliza openly; the town’s credit closed to her because a ledger’s social sanction often mattered more than coin. A few civic-minded men—Harrison Wells among them—acted as intermediaries, guarding trust funds and making business transactions routed through white hands. A small network of free black families quietly offered help: supplies delivered after dark, children tutored in secret, women’s solidarity that was not spoken of in drawing rooms.

At Belmont, the division of property severed what remained of any community on the estate. Workers and families, the marrow of the plantation’s labor, were parceled and sent like cargo. Samuel—the field hand who had once leaned the plow and who later escaped North—would later write in his memoir of the sound that the auctioneer’s hammer made when the property of human life was laid out. He would say that Eliza cried on the day the men were divided, because her freedom could not extend to everyone she loved. “She was saving her own children,” Samuel would remember, “and that was freedom and cruelty wrapped in one.”

Eliza moved into the North Tract in the spring of 1855. For the first time in her life she had the word “mine” to attach to land. For the first time she and her children slept beneath a roof she could call their own. Marcus, who had once been taught letters in secret by the very man who had enslaved him, now read with a light in his face that had never been permitted. Sarah and little Thomas learned arithmetic beside the window that watched the cotton fields. They were free in paper and increasingly in practice, though the town’s eyes followed them like weather.

But the air was brittle. The free black community in Natchez embraced Eliza for the courage she had shown, and they protected her in the practical ways that people who have known danger know how: safe routes to the river, quiet purchases, and a network of informal schools. Yet being neither wholly part of the white world nor of the black world made life precarious. The children were too white for the colored schools and too black for the white academies; the trust fund was managed by white men who kept their own profits in plain sight; people in Natchez treated the very idea of a black landowner like something combustible they might bend or break.

And the war—inevitable as a storm cloud—approached. By 1861 the country split according to the map of fear. Marcus, grown and restless, argued to leave Mississippi and seek sanctuary where skin and coin might buy safety. Eliza refused. The land had been given by the father who had produced her children; it was theirs now, and to leave would be to concede that the society’s worst prejudice had won. Marcus, proud and impatient, enlisted in the Union Army in 1864. He would come home with a blue coat and a different kind of authority.

The plantation economy withered under the stress of secession and war. The South’s cotton markets collapsed, the machinery of slavery dissolved by force and law, and Belmont’s lands, both north and south, became maps of loss. In time, the Thornon children scattered, careers carried them away from Natchez, and Margaret died—older, hollowed by years of defending a world that left her hollow as well—leaving the remainder of her estate to a generation that had no appetite for rebuilding. She and Eliza never reconciled; there was a line no circumstance would erase.

Eliza lived into the late nineteenth century. She watched her children prosper in ways a woman born into chains could scarcely imagine: Marcus as a teacher back home in Reconstruction’s fragile light; Sarah marrying a minister and moving to Philadelphia; Thomas studying law in Ohio, becoming one of the earliest black attorneys of the postwar era. The years hollowed the rancor of the courtroom into a kind of practical memory. The North Tract shrank in value under the ruin of the old agricultural system, but inside the house there were books and discourse and the steady management of what they had, and by then Eliza’s authority in those rooms was as absolute as any law had made it.

When she died in 1889, her children sorted the belongings they had been raised upon—furniture, ledgers, the small brass compass that had belonged to Robert. In the bottom of a locked drawer they found a box of letters bound in twine: Robert’s handwriting in the tight, guilty script of a man trying to be honest to the end. He had written with the mixture of confession and self-justification that monsters often mistake for absolution. The letters did not redeem him; they re-opened the wound he had created. “I tell myself that what I have is love,” one read. “But late at night, I know the truth: you cannot refuse that which you are told you must accept.”

Those letters became a new inheritance. Marcus kept a few translating them for his students in the Freedmen’s School he ran, teaching a new generation how to read both letters and the society that had produced them. He taught history as a living thing: the man who believed himself benevolent and the woman who could never be whole for being owned. He taught that confession without restitution was insufficient and that the structures of power persisted even after law changed.

If the story serves any use, it is because it resists neat endings. There was no cinematic reconciliation in which everyone forgave and all the broken pieces glued together. The cruelty of slavery had not been undone by a paper or a dying man’s courage. Instead, what happened was complicated and real: some people suffered in ways that had nothing to do with their moral deserts; others found, against long odds, ways to create lives that refused the definitions their society would give them.

In the years after the war, Marcus returned to Belmont and, wearing the careful patience of the teacher, planted trees along the northern border of the tract. He taught school in the main room of a small house and read aloud to children who had never had books. When white visitors came in later years to admire the restored columns and the plantation’s sweep of lawn, he met them at the gate and smiled but never invited them over. He held the land as both a reminder and a promise: the promise that infrastructure and memory could not remove the truth of what had happened.

One late autumn, when the magnolias were dense with the heavy chill of an approaching cold snap, a young professor from a northern university came down from the river steamboat to look at the restored North Tract. He wanted architecture and provenance; what he left with was a story. He sat for an afternoon beneath the same maples Marcus had planted and read through the letters and the ledger books. He left with a manuscript and, more quietly, with the decision to advocate for a plaque at the entrance to Belmont that named what no monument had yet named: that the estate had been built on stolen labor, that part of it had been given back by a man incomparable to his crime, and that a family—black and white—had been ruined and remade by those inconsistent acts.

When the plaque finally went up—years after Marcus had died and his own grandchildren had scattered—the town debated in the same patterns as before. Some called it unnecessary history; others called it overdue. But the presence of those words at the gate made a difference. People read them as they passed, and for some the reading was a small, private act of reckoning.

Of the people who had survived, Eliza’s grandchildren lived into the twentieth century as teachers, ministers, and lawyers. They taught children in classrooms that had been unthinkable when Eliza first laid eyes on a ledger. They preserved what fragments of property and dignity their grandmother had secured and turned them into social infrastructure: schools, churches, meeting places where people gathered to plan a life that would not be stolen.

In the end, the story the sealed room brought to light was not an apology wrapped in a neat moral. It was a history of people making small choices within monstrous systems. Some choices were brave, some cowardly; some cruel, some kind. Robert Thornton tried to do at the end what he had refused for years: to make amends. But amends cannot replace lost childhoods or the daily theft of autonomy. Eliza took what she could and lived well within it, refusing to be hollowed out by the hatred that had been thrown her way. Margaret died tired and broken by the defense of a world that had only served to protect her in appearance.

When visitors ask what they might take away standing beneath the columns of Belmont, Marcus’s daughter would say, “Remember the names of those who had no lawyers. Remember those who did.” She would point not only to the parlor that had erupted into scandal, but to the kitchen house, to the small rooms at the bookkeeper’s quarters where the real lives of the place had been arranged. “The law,” she said once, “can give you a piece of paper. It cannot give you back the years men took from you. It can make you free in the world’s book, but it cannot always buy back the loss that comes when your will is not yours.”

If there is any mercy in the story, it is in the quiet acts: in Aunt Ruth’s truth-telling on the witness stand; in the small network of free black women who delivered baskets to Eliza’s back door; in the teacher who read Robert’s letters not as absolution but as a caution; in Eliza’s own quiet care of her children and in the way she ran her land with a deliberate tenderness to the people left in her trust. Mercy, if it existed at all, existed not in the dying man’s attempt to undo a lifetime of theft, but in the persistence of those who took the shards of that theft and made lives out of them.

So the Belmont fields still stand, and the North Tract remained in the hands of Eliza’s descendants for generations. They did not forget the circumstances of their origin. They planted, they taught, they argued, and sometimes, at night, when the cicadas sang thin and insistent, they read aloud from the letters to understand the weight of a man’s attempts to make right what could not be made right.

There was no neat moral. There was simply the persistence of people who had learned to turn what they had been given—land, a ledger, a narrow piece of justice—into something that, imperfectly and stubbornly, held the possibility of a different tomorrow. Robert Thornton’s last act destabilized a world, and within its shock, people were forced to choose. Some chose revenge, some chose litigation, some chose exile, and some chose to teach.

Eliza chose, finally, to teach her children to read, to manage, to keep receipts and not be miscounted. That, perhaps, was the most radical inheritance of all. In the ledger of history, people sometimes seek hero or villain; in truth, most of us are both. The only merciful act is to acknowledge what was done and to build, as best we can, structures that make the repetition of such crimes more difficult. The plaque at Belmont’s gate is only a start. The education started by Marcus and his siblings is the work that mattered most.

When you pass by and stand on the threshold, do not look only to the columns and the wax-sealed will that remade lives. Look, too, toward the fields and the kitchen house, toward the rooms where the real lives of this place found ways to grow despite what the law could take. Remember that freedom is not a single act, but a long insistence, and that in the end, the people who made the most difference were usually the ones who had the least to spare.

News

Unaware Her Husband Owned The Hospital Where She Worked, Wife Introduced Her Affair Partner As…

Ethan’s eyes flew open. He didn’t think. He didn’t weigh possibilities. He didn’t do the billionaire math of risk versus…

A Single Dad Gave Blood to Save the CEO’s Daughter — Then She Realized He Was the Man She Mocked

He pointed past Graham’s shoulder toward the Wexler family plot, eyes wide like they didn’t belong to him anymore. “What……

She Lost a Bet and Had to Live With a Single Dad — What Happened Next Changed Everything!

Behind him, two of Grant’s security men hovered near the black SUV, looking uncomfortable in their tailored coats like wolves…

She Thought He Was an Illiterate Farm Boy… Until She Discovered He Was a Secret Millionaire Genius

Then a small voice, bright with terror, cut through the hush. “Sir! Sir, I heard it again!” Grant’s eyes landed…

Come With Me…” the Ex-Navy SEAL Said — After Finding the Widow and Her Kids Alone on Christmas Night

Malcolm’s jaw tightened. People had been approaching him all week: journalists, lawyers, charity people, grief-hunters with warm voices and cold…

“Can you give me a hug,please?”a poor girl asked the single dad—his reaction left her in tears

Bennett lifted a hand and the guard stopped, instantly. Power was like that. It could silence a boardroom. It could…

End of content

No more pages to load