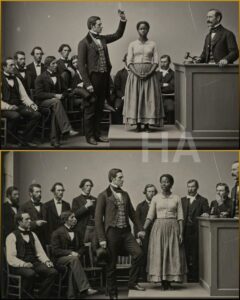

No one lifted a paddle.

It wasn’t that the men lacked appetite. Moments earlier, they’d shouted bids over boys and women the way gamblers shout at cards. Now they stared at boots, studied ceiling plaster, examined their own knuckles as if reading palm lines.

Forier tried again, voice tight. “Surely, gentlemen, you can see the obvious value before you. Three hundred, then. Do I hear three hundred?”

Nothing.

And Deline stood there with her hands clasped, serene. Almost… knowing.

It was then James Lavo entered the exchange.

He wasn’t Louisiana aristocracy, but he was wealthy enough to pretend he belonged. The son of a cotton trader who’d built his fortune on the river and the ledger, James Lavo was thirty-eight and ambitious in the way men are ambitious when they’ve purchased every object they were told to want, yet still feel the world withholding its approval.

Three years earlier he’d bought Bellamont Plantation, thirty miles upriver. Greek Revival columns. Wraparound veranda. Twenty-three rooms. Twelve enslaved people inside the house maintaining the elaborate fiction of gentility, and many more out in the fields turning sweat into cotton into money.

James had arrived late, delayed by business at the port. He pushed through the crowd, annoyed with himself for missing the earlier lots.

Then he saw Deline.

The feeling hit him so hard he later described it like a blow to the chest. He stopped moving. The room narrowed. The murmur of the hall dimmed until he could hear only his own breath and the faint creak of the platform beneath her feet.

Forier was pleading now. “Two hundred! This is robbery, gentlemen. Someone must recognize the extraordinary nature of—”

“One thousand.”

The voice rang out clean and confident.

Every head turned as if pulled by a string.

James Lavo stepped forward, eyes fixed on the platform. “One thousand American gold.”

Forier’s expression changed, but not into triumph. Relief, yes, and something else, like alarm.

Before the auctioneer could respond, an elderly man near the front stood abruptly. Etien Devo. Forty years a successful planter. A man whose authority came from age and the fact that most people had learned not to argue with him.

“Mr. Lavo,” Devo said, and the room leaned toward his words, “I must advise you to reconsider. There are circumstances surrounding this particular acquisition that warrant extreme caution.”

James turned, jaw set. “If there are defects or medical conditions, they should be disclosed in the sale documents. I see no such notations.”

“The defects,” Devo replied slowly, “are not of a nature that appear in official documents.”

A ripple of uneasy laughter moved through the crowd and died on contact with Devo’s face. He didn’t smile.

“Three men have owned that woman,” he continued. “Three men of considerable wealth and standing. All three are now dead.”

The air thickened as if the humidity had turned to syrup.

“Edoir Merier died in his bed with no mark upon him,” Devo said. “Yet the doctor who examined the body swore his expression was one of absolute terror. Philippe Rousseau was found in his library with a pistol in his hand and a bullet through his brain, though he left no note and had shown no signs of despair. And just last month, Antoine Boragar walked into the Mississippi River at midnight, fully clothed, pockets weighted with stones.”

Someone’s wife made a small sound and covered it with her fan.

“I knew all three men,” Devo said, voice heavy. “Each one, in the weeks before his death, underwent a change. Withdrawn. Agitated. Speaking of dreams that gave them no rest. And each one mentioned her.”

He gestured toward Deline.

“Whatever that woman is, Mr. Lavo… she is not merely a slave. She is a judgment waiting to be delivered.”

James laughed, but it rang hollow, like a glass tapped with a knife. “You’re asking me to believe in ghost stories and plantation superstitions.”

Devo’s gaze didn’t flicker. “Then you are a fool,” he said simply, and sat down.

Pride has killed more men than bullets.

James Lavo’s pride had been engaged in front of the assembled elite. To back down now would be to confess weakness, and weakness was the one thing new money could never afford.

He turned back to Forier. “My offer stands. One thousand. Unless someone wishes to bid higher.”

No one did. Not even a “one thousand and ten” out of spite. Not even a drunken joke.

Forier swallowed. “Very well,” he said, voice thin. “Sold to Mr. James Lavo for one thousand dollars.”

He almost added something else. A prayer, perhaps. He caught himself.

“The paperwork will be prepared immediately.”

As James approached the desk to complete the transaction, he passed close to the platform. Deline turned her head slightly and met his eyes.

Later he told his house manager it felt like a door opened in his mind, a door he hadn’t known existed.

In the moment, flushed with victory, he merely nodded as if acknowledging a fine horse.

“Yes,” Deline said softly when he looked at her, her voice smooth as velvet with something colder beneath. “Master.”

The notary, Baptiste Chioalier, recorded the transaction with unusually meticulous detail. In the margin of the ledger he wrote an extra note, careful and ominous:

Buyer was warned by E. Devo and others present. Proceeded despite unanimous counsel to decline purchase. This notation made for the record should future inquiry become necessary.

The Road to Bellamont

James Lavo rode inside his finest carriage. Deline sat beside the driver on the exterior bench, as if she were luggage.

The driver was Moses, an older man enslaved by the Lavo family for twenty years. He had learned the safest kind of conversation: short, careful, polite.

Still, curiosity is stubborn. On the road, while green cane fields blurred past and oaks hung with moss like old sorrow, Moses tried.

“Can you read?” he asked.

“Yes,” Deline replied.

“Write?”

“Yes.”

“You know house work?”

“I do.”

He hesitated, then asked the question that had been itching at the back of his throat. “Them men… them owners before. Folks say bad things happened.”

Deline’s gaze stayed on the road ahead. For a long moment she said nothing, and the carriage wheels sounded too loud.

Then she turned slightly, eyes deep as river water at midnight.

“Sometimes, Moses,” she said, “the universe keeps its own accounts. And some debts can only be settled in full.”

She smiled, but it wasn’t comfort. It was the expression of someone holding a truth sharp enough to cut through bone.

Bellamont appeared near sunset: white columns, wide veranda, the proud face of a system built on stolen lives.

James’s wife, Margarite, stood waiting.

She was thirty-five, thin, and carried her Creole name like a shield. She had married James for his money; he had married her for her family’s respectability. Their household ran on cold civility, not love.

When Deline stepped down from the carriage, Margarite’s expression shifted from curiosity to alarm so fast it looked like fear had slapped her.

“James,” she called, gripping the railing. “What have you done?”

James frowned, annoyed by her tone. “I’ve acquired an excellent house servant at a remarkable price. Deline will serve as your personal maid and assist in managing the household staff.”

“I do not want her in this house,” Margarite said, voice tightening. “Send her to the quarters. Put her in the fields. But do not bring her into my home.”

James’s face darkened. It wasn’t the request. It was that she dared make it in front of the enslaved people, where his authority had to look absolute.

“You will mind your tongue,” he snapped. “I am master of this house. I decide where my property is assigned.”

He turned to Deline. “You will be shown to the room off the kitchen. Report to Celeste, the house manager. She will explain your duties.”

“Yes, master,” Deline said softly.

The words were obedient. The eyes were not.

Celeste’s Diary

Celeste had managed Bellamont’s domestic operations for over a decade. Fifty years old, steady hands, steady mind. She had seen cruelty, and she had survived it by becoming useful, by making herself necessary.

Her diary, found decades later in an attic trunk, would become the clearest record of what happened next.

May 15th, 1854.

The master has brought a new girl into the house. Her name is Deline, and from the moment she stepped through the kitchen door I felt a cold wind blow through my soul despite the warm evening. The other servants feel it too.

Marie crossed herself when Deline passed her in the hallway. Young Thomas dropped a tray of dishes and fled to the quarters, saying he couldn’t bear to be in the same room with her. When I asked him why, he shook his head and said: “She ain’t right, Miss Celeste. There’s something behind her eyes that ain’t human.”

I tried to dismiss it as superstition. But when Deline entered the kitchen, all the candles flickered at once though there was no draft. The stew I had simmering began to boil over violently though it had been steady for hours.

And when she looked at me, I felt like she could see every sin I ever committed. Every cruel thought I ever swallowed and called it survival.

On paper, Deline’s duties were simple: attend to Margarite, maintain her wardrobe, assist with correspondence and social arrangements.

In practice, she became a presence Margarite could not escape.

Margarite’s dresses were pressed perfectly. Her hair arranged with flawless hands. Her rooms spotless.

And within a week, Margarite began to come undone.

Food tasted like ash. Sleep became a battlefield. She woke screaming but could not remember the dreams. Her hands developed a tremor no laudanum could calm. Dark circles sank under her eyes as if someone had smudged her with exhaustion.

One evening, exactly a week after Deline’s arrival, Margarite stormed into James’s study.

Moses was there serving drinks. He later testified he kept his eyes down, but his ears had nowhere else to go.

“She watches me,” Margarite whispered, nearly hysterical. “Constantly. Even when she’s not in the room, I feel her eyes. When she touches me, when she fastens my dress, her fingers are ice cold and I feel something draining out through my skin.”

“You’re being ridiculous,” James said, but Moses noted his voice lacked conviction. “She’s doing her assigned work. If you’re unwell, I’ll send for Dr. Beauchamp.”

“No doctor can help with this,” Margarite hissed. “That woman is not what she appears. I see things in the mirror when she stands behind me. Shadows that move wrong. Faces that aren’t hers reflected where hers should be.”

James’s patience snapped. “Enough. I will not tolerate this hysteria. Compose yourself or I will have you confined to your rooms.”

Margarite stared at him for a long, quiet moment. Then her expression shifted. Not fear. Not anger.

Pity.

“She has you already,” Margarite said softly. “I can see it. The way your eyes linger on her. You think it’s desire, James. But it’s not. It’s a hook being set, and you’re too arrogant to feel it.”

She left.

Three days later, Margarite Lavo was found at the bottom of the main staircase, neck broken. The coroner ruled it an accident.

Celeste wrote something else.

May 25th, 1854.

Madame is dead. They say she fell but I know better. I was in the hallway when it happened. I saw Madame standing at the top of the stairs, and I saw Deline standing beside her. They were speaking in low voices. Then Madame screamed, not a scream of fear, but of realization. Like she’d just seen a truth too large to hold.

Madame stepped backward toward the stairs and I swear on my mother’s grave I saw Deline make the slightest gesture with her hand, just a small movement of her fingers. And Madame went over backward like she’d been pushed by an invisible force.

Deline came down the stairs slowly with appropriate concern. But when she passed me, she leaned close and whispered: “One account settled. The balance shifts.”

The Hook Sets

Margarite’s funeral was performed with ceremony. James played the grieving husband convincingly enough for polite society to accept it. Yet several attendees noticed his grief looked performed, like a man remembering lines.

What they noticed more was the way his eyes kept drifting to Deline standing with the other house servants at the back.

Father Benedict Rousseau later wrote in a letter that James looked at her “the way a drowning man looks at the surface of the water he can no longer reach.”

After Margarite’s death, Bellamont changed.

James, once harsh but consistent, became erratic. Some days he rode the property for hours, barking orders, demanding impossible perfection. Other days he locked himself in his study and sat in darkness with untouched meals outside his door.

But one thing remained constant: Deline.

She became more than a maid. She moved through the house with authority James never formally announced, yet everyone felt. She gave orders and they were obeyed, because James’s will seemed to trail behind hers like a shadow.

Whispers ran through the quarters at night.

“He’s being ridden,” old Ruth said, a woman who claimed her grandmother had carried Haitian conjure knowledge in her bones. “Spirits attach to the living, feed on them slow, use them up like candles.”

Celeste’s diary grew more frantic.

June 12th, 1854.

Cannot sleep. When I close my eyes, I see her face. The master is a shell now. Tonight at dinner he barely ate, barely spoke. After, I watched him follow Deline up the stairs like a dog following its master. There is no other word for it.

People are leaving. Two field hands ran last week. Marie fled in the night. I know I should go too, but something keeps me here. Loyalty, perhaps. Or the terrible fascination of watching a darkness unfold and knowing someone must write it down.

On June 18th, James did something that shocked the region. He went to New Orleans and signed papers granting Deline her freedom.

The same notary, Baptiste Chioalier, noted in the margin:

Mr. Lavo appeared deteriorated. Weight loss apparent. Hands trembling. Eyes unfocused. When questioned, he responded: “She was never mine to own. I see that now. Some debts transcend property laws.”

Freedom papers did not mean Deline left.

If anything, she became more dominant.

She moved into Margarite’s former rooms. She wore Margarite’s dresses. She sat at Margarite’s place at the dinner table across from James while he ate in silence and stared as if the walls were teaching him a lesson he couldn’t stop learning.

Then she had James dismiss Garrett, the brutal overseer who had terrorized the field hands for years. James gave him one hour to leave the property.

When Garrett protested, threatening authorities, James stared with empty eyes and said, “You will leave now, or you will never leave at all.”

Garrett left pale and wordless.

Celeste wrote:

June 30th, 1854.

She is the mistress now in every way that matters. I saw her watching Garrett ride away. She was smiling. Not a pleasant smile. A smile like someone checking items off a long list. I heard her murmur something. It sounded like: “Five names left.”

The List

By July, the surrounding planters began to notice Bellamont had become a locked mouth. Deliveries were met by hollow-eyed servants. Social calls went unanswered. Letters requesting James’s presence were ignored.

On July 4th, Etien Devo rode to Bellamont.

Moses met him at the gate, voice urgent. “You best not come up to the house, Mr. Devo. Things ain’t right.”

Devo insisted.

What he later wrote to his attorney was sealed with instructions not to open unless he died suddenly, but parts survived in copies.

The house felt wrong, Devo wrote. Cold like a grave despite the summer heat. Windows shuttered in daytime, leaving rooms in perpetual twilight.

He found James in the study. James barely acknowledged him.

When Devo asked about his health, James said, “I am learning, Etien. Learning what I should have been taught long ago. That actions have consequences that echo through time. That debts accumulate across generations.”

Devo tried to remind him of responsibilities and society.

James laughed, bitter. “Position. Society. Comfortable lies to justify the unjustifiable. I see clearly now. The bill has come due.”

Then Deline entered.

She moved like the floor had forgotten how to resist her. She set a hand on James’s shoulder and Devo swore James flinched, not away but inward, as if pain and pleasure had become the same wire.

Deline looked at Devo. “Mr. Devo,” she said softly. “How kind of you to visit. But my master requires rest now. Perhaps you should return to your household.”

Her eyes held him like a scale holds weight.

“After all,” she added, “you have much to reflect upon regarding your own accounts.”

Devo left quickly. Riding away, he looked back once. She stood on the veranda watching him.

Even at a distance, he felt measured.

Whitmore

In late July, a neighboring planter named Charles Whitmore arrived uninvited and belligerent. He was known even among cruel men as unusually cruel, the sort who treated brutality as entertainment.

He pounded on the front door demanding James.

Deline answered instead.

“I’ll speak to the master of this house,” Whitmore snarled, “not his fancy bedwarmer. Tell Lavo to come out or I’ll drag him out.”

“How interesting,” Deline said calmly. “Master Lavo has been expecting you.”

“Expecting me?” Whitmore scoffed. “I sent no word.”

“Not expecting in that sense,” she replied. “Expecting because your name appears on a particular list. A list of accounts requiring settlement.”

Whitmore’s hand went to his pistol. “You dare speak to me like that?”

“You should have many things, Mr. Whitmore,” Deline said, voice soft, sharper underneath. “You should have mercy. You should have conscience. You should have hesitated before you beat that fourteen-year-old girl to death last month for breaking a dish.”

The porch went still.

Whitmore’s face changed, red draining to white. “That was… an accident. The girl was clumsy.”

“She was a child named Sarah,” Deline said, and the name landed like a stone. “She had a mother named Ruth who still weeps. She had a younger brother who no longer speaks because watching her die broke something in his mind.”

James emerged then, but he was no longer the man who’d walked into the St. Charles Exchange. He’d lost weight. His skin had taken on a gray cast. His eyes looked aged decades, as if each blink contained a memory he never asked for.

“You’re on my property uninvited,” James said quietly. “You should leave.”

“Not until you explain what this woman is saying,” Whitmore snapped. “Spreading lies about me.”

“Are they lies?” James asked. “Did you not beat Sarah to death? Throw her body into an unmarked pit? Threaten her mother if she spoke?”

Whitmore’s grip tightened on the pistol. “Those are my affairs. My property to manage.”

“It concerns me,” James said, voice low, “because I’m learning the cost of such management. Every blow struck. Every life taken. These things do not vanish. They accumulate. Eventually the bill comes due.”

Then Deline made a small gesture with her fingers.

Just that.

Whitmore clutched his chest. His face contorted as if something inside him had turned on him. He stumbled, gasping, pistol falling from his hand.

“What… what are you doing to me?” he choked.

“I am doing nothing,” Deline said calmly. “Your own heart is rebelling against you.”

Whitmore collapsed. By the time Moses and Thomas reached him, he was dead.

The doctor later claimed apoplexy, years of drink, natural failure.

In private notes found long after, the doctor wrote: The man’s heart was destroyed as if consumed from within. Impossible.

After that, the field hands looked at Deline with fear, yes, but also something else. Not worship. Something closer to the feeling a drowning person has when they realize the river has a current and the current is finally turning.

Deline walked among them in the evenings. She asked names. Stories. Where children had been sold. Which wives had been taken. Who had died and where they were buried when no markers were allowed.

One man named Josiah later testified that she listened to him describe three children sold away to settle James’s gambling debts, each to a different buyer across different states.

Deline put a hand on his shoulder. “Their names will be added,” she said. “All separations will be answered for.”

Meanwhile, James began compiling a ledger, night after night, in the library.

Names. Dates. Transactions. Families. Deeds.

A map of suffering written in ink.

Celeste wrote:

August 7th.

He is not entirely himself anymore. When he looks at me, I see an awareness that seems to come from outside him. Today he asked: “Do you know how many lives my family destroyed to build this plantation?”

He counted. Seven hundred forty-three names in the ledgers, and those are only the recorded. Children born and sold before they could be listed. Deaths called natural that were really murder by neglect.

He said: “The true accounting is beyond calculation, but she knows. She remembers all of them.”

When Celeste tried to bring Dr. Beauchamp, Deline met the doctor at the door.

“The master is not receiving visitors,” she said.

“I must insist,” the doctor began.

“You are also,” Deline cut in, consulting a small notebook, “the owner of six enslaved people. Three purchased from Antoine Boragar’s estate, including a young woman named Marie, purchased for purposes no physician should engage in with anyone under his power.”

The doctor’s face went gray. “I…”

“Would you like me to continue reading from your account,” Deline asked gently, “or would you prefer to leave now and reflect upon your impending reckoning?”

He left.

Six weeks later he hanged himself, leaving a note: The inventory of my sins exceeds my capacity for living with them.

The Night the House Filled With the Dead

By mid-August, field labor changed. There was no overseer, no whip. Yet the work continued, organized around Deline’s instructions. She had them harvest swamp plants, dig up bundles buried long ago, objects recognized by those who remembered old knowledge: bones, hair, herbs, cloth tied tight.

Old Ruth said, voice trembling with something like recognition, “She’s gathering what our grandparents buried. All the old power. She knows where it is.”

On August 18th, James emerged from his study and gathered everyone before the main house.

He looked like a man hollowed out, but his voice was clear.

“I have completed the accounting,” he announced. “Every name. Every life destroyed by my family and those like us.”

He turned to Deline on the veranda. “I understand now why you chose me. Not because I was the worst. But because I could be awakened. I am the instrument of my own judgment. Is that correct?”

Deline’s expression remained unreadable. “You are beginning to understand.”

That night, controlled fires burned in precise locations across the property. The smoke carried a scent like summoning. Like a door being opened.

On August 19th, the air grew oppressive, animals behaving strangely. Dogs refused to bark. Horses trembled. Birds circled overhead under a moonless sky.

At precisely midnight, lights appeared in every window at once, not warm candlelight, but cold blue-white luminescence that hurt the eyes.

Singing filled the plantation.

Not from human throats.

From the earth. From the walls. From the air itself.

Thomas crept close enough to see figures moving through the rooms. Not vague shadows, but distinct forms, dozens, hundreds, men and women and children, faces marked by lives used up and discarded.

They moved toward the study where James sat at his desk with the ledger open.

They came through walls as if walls were only suggestions.

Deline stood in the entrance hall, and witnesses later said her beauty had changed into something beyond human, like the terrible perfection of fire: unstoppable, indifferent to pleading.

“The accounting is complete,” she announced, and her voice carried everywhere. “Every name recorded. Every sin documented. Every debt calculated. Now comes the collection.”

She turned toward James.

“James Pierre Lavo,” she said, “you purchased me believing I was property. But I was never a slave. I am something older. I am the memory that will not fade. I am the debt that comes due. I am the justice that arrives when all other justice has been denied.”

James looked up, and those close enough to see his face later said he did not look afraid.

He looked… relieved.

“I know,” he whispered. “I’ve known for weeks. You are the reckoning our actions demanded.”

Deline moved closer. The congregation of the dead shifted with her like a tide.

“Payment requires more than your death,” she said. “Death is too quick. Payment requires transformation.”

And then she spoke the sentence that turned James’s last human breath into something final:

“You will become what you once owned. You will know what you once inflicted.”

James stood. He walked to the center of the room.

And he dissolved.

Not blood, not bones. He broke apart like smoke in wind, fragments drawn into the multitude as if his life were being poured into a collective vessel.

Some witnesses called his final expression agony. Some called it ecstasy. Some said it was both, because true understanding can feel like burning.

The lights flared blindingly bright, then went out all at once.

When vision returned, the house stood empty.

No spirits. No Deline. No James.

Only the ledger remained open on the desk, pages filled with names and dates and accusations in James’s deteriorating hand.

What People Did With the Story

In the weeks that followed, reports spread across Louisiana and beyond: prominent traders dying in strange ways, men waking with voices that weren’t theirs, sudden confessions spilling from mouths that had spent years ordering silence.

Authorities ruled James Lavo had abandoned his property. Bellamont was sold to settle debts, but no buyer would live in the main house. The enslaved people were dispersed to other plantations, the cruelty continuing in new locations as if relocation could erase guilt.

Yet the story traveled anyway, carried through the underground networks of those who had always been forced to remember. In those whispers, Deline was not a ghost story. She was a ledger made flesh. A reminder that the past is not dead, it is only waiting.

Decades later, Bellamont’s main house burned under mysterious circumstances. People claimed they heard singing as the structure collapsed, hundreds of voices raised in something that sounded like celebration and mourning woven together.

In 1923, archaeologists found a stone chamber beneath the ruins filled with sealed clay vessels marked with West African symbols. Soil samples labeled with names and dates, like pieces of stolen ground returned to the dead as proof they had not been forgotten.

And at the center, one vessel marked with the name Deline, containing what looked like the same ledger, except the entries continued beyond 1854.

At the very end: The accounting continues.

In 1967, on August 19th, over a thousand people gathered at the site without any formal organization. Black and white, young and old. They stood together in the dark and heard singing that did not come from their own mouths.

One woman, a civil rights organizer descended from Bellamont’s enslaved community, later said she saw Deline at the center of where the house once stood, tall and calm, smiling not with satisfaction but with encouragement.

As if to say: You’re still here. You’re still walking forward. Keep going.

And in 2019, a descendant of Charles Whitmore came to the site seeking a way to hold his family history without being crushed by it. He described meeting a tall woman with deep eyes who said nothing aloud, yet somehow made him understand:

Acknowledgment is only the beginning.

Repair is a practice, not a speech.

Every generation chooses whether to keep the harm moving, like a poisoned river, or to build something else.

He left feeling lighter, not forgiven, but permitted to try.

A Humane Ending That Isn’t a Fantasy

People prefer endings that close the book, lock the door, and let everyone sleep.

This story refuses that comfort.

Because what happened at Bellamont, whether one calls it supernatural justice or the psychological collapse of men finally forced to see their own crimes, points to the same truth:

Cruelty creates debt. Debt does not dissolve because paperwork says it can. Memory is not a museum artifact. It is a living thing, carried in bodies, families, and land.

If Deline is anything, she is a question posed to every era that congratulates itself on being “past” its sins:

What are you doing with what you inherited?

The most human part of this story is not the blue-white light, not the spirits in the hallway, not the man dissolving into consequence.

It’s the moment the living gather in the dark, hear the song, and choose not to run.

It’s the choice to remember names.

To tell the truth even when it burns the tongue.

To plant trees where a house of suffering once stood.

To say: You mattered. You were here. We will not pretend you were invisible.

That is how accounts begin to shift.

Not through terror alone, but through transformation.

Not through forgetting, but through witness.

And somewhere, whether in legend or in the quiet pressure of history that refuses to stay buried, the accounting continues.

News

🚨Thirty-seven nannies quit in fourteen days. Some cried. Some ran. One called it a house that needed an exorcist.

“THE TIME BOMB IS TICKING — AND THIS TIME, IT’S PERSONAL.” Virginia Giuffre — the woman who exposed Jeffrey Epstein’s…

A Millionaire Fired 37 Nannies in Two Weeks, Until One Domestic Worker Did What No One Else Could for His Six Daughters

Jonathan closed his eyes. In his mind, he saw Hazel’s face on the staircase, the way she watched strangers the…

A Billionaire Found His Granddaughter Living in a Shelter —Where Is Your $2 Million Trust Fund?

Malcolm’s throat tightened. “Kioma lives there.” “Yes,” Devon said. “It’s a mansion. Worth about two-point-three million. Kioma Johnson lives there…

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

End of content

No more pages to load