That night, Helena could not sleep. She sat in the dark and listened to the convent breathe around her. She had been taught that to take a life was to steal a spark of God’s own mystery, an act that would scar a soul beyond repair. Yet that was a lesson read from the scripture by men who burned villages and baptised blood in the name of purity. Where, she wondered, is the law when those who write it are the first to break it?

Weeks passed. The war narrowed like a funnel. News came in whispers and far-off rumbles—retreat, collapse, the eastern front unraveling. The men at the Sacred Heart did not quiet down; if anything, the finality of doom made some of them louder. They joked with one another over brandy, debated pensions and promotions, and told stories to shame the memory of children into believing in nothing. Helena listened and learned their patterns—the Monday washing, the Tuesday inspections, the Sunday lunch when all were expected to attend. That, she realized, was the key.

She also found things in the convent’s basement: a small tin of whitish powder, marked simply for rodent control, something the old brothers had used to battle the perennial mice that nested in the rafters. It was a substance kept behind double locks and rarely mentioned. In other hands it was merely a nuisance remedy. In her hands it became a measure of choice. She did not count grams. She did not deliberate with chemistry or manuals. She weighed the memory of a woman’s skull against the children who would no longer have a future if these men were allowed to fade into ordinary lives. The calculus of the oppressed is not a science; it is a ledger of pain.

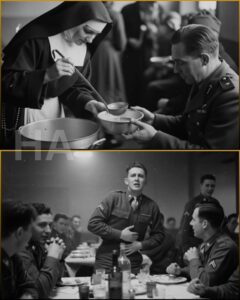

On a Sunday in March—the snow at last grudgingly giving way to the first sticky mud of spring—the dining hall was full. The officers were as oblivious as men can be when the world is burning: cheerful, loud, confident. Their laughter carried to the rafters like bird calls. The rules said the meal must be uniform, and so she prepared the soup as she always did: a broth to make worn-out men unthinking, a spoonful of comfort for those who thought themselves entitled to it. She put the powder into the pot like one might put sugar in a preserving jar—disguised by heat and broth and the murk of cooking, hidden like a truth wrapped in bread.

Helena served the soup. She balanced the bowls, presented them, and watched as men she had learned to read as if they were weather patterns ate and told old jokes. One of them, a young lieutenant who laughed too loudly at executions and ate too quickly at meals, asked for seconds. He ate three bowls as if he were filling himself against a sudden frost. Helena placed each bowl down and felt each look like a small stone in the hollow of her chest. When the first of them clutched his stomach and swore it was his brandy, the room filled with the sound of someone discovering an unexpected hole in the floor.

The convulsions came not as cinematic clarity but as a sequence of shocks: a man retching, another collapsing, a plate skittering and shattering, a collar stained, voices thin as glass. For a moment the world contracted to the distance between her and the doorway. She might have stayed to watch. She did not. The convent had taught them many secrets—passageways, old tunnels for drainage and waste used in another century’s needs. She had learned their maps during the long nights of scrubbing. When punishment would come, it would be swift and absolute. She unpinned her habit, folded it, and dressed herself in the plain clothes she had packed away years ago like an answer she had never intended to use.

She crawled into the ancient crawlspace beneath the kitchen, the brickwork worming around her like a sleeping animal. In the dark she moved by memory more than sight, skin scraping stone, breath shallow. When she emerged beyond the perimeter hours later, the town was a geometry of smoke and distant cries. She stumbled toward the edge of the wood with a small satchel and a heart that felt like a bell struck too quickly.

Word spread faster than bullets. The SS commander in Posen did not weep; he roared. A manhunt began. They dragged families from their homes; they shut doors and pounded on them until splinters flew. They shot men in the square as a warning. Helena watched the flames from a ridge and the smoke rose like a verdict written in the sky. She thought in that moment of the woman on the road, of the children who would never know their mothers, of faces lined with grief. A terrible arithmetic took hold of her—forty-seven violent men taken in a single, cunning strike, two hundred innocents punished to prove a point. The ledger of war is written in pain, but never with even hands.

For the next fortnight she moved with a handful of resistors who had somehow become her escorts through the night. Potter—barked name, kind eyes like a man worn by truth—Christina, a woman with a pistol and flinty humor, and Jacob, a boy who seemed older than his years. They led her across frozen fields and through towns where shadows moved like ghosts. German patrols passed close enough to hear the rasp of their breath. Once a soldier with a scar on his chin held a lantern over Helena’s face and asked questions in a language she had not been trained to answer in. Christina said she was deaf, that she had been struck by a fever in youth; Potter handed over forged papers with hands that trembled slightly around the edges. The soldier let them go because, later, Potter told her, some men were simply tired of killing. Even a small mercy can look like a miracle in the last days of a war.

They reached the British lines at last, where the orange sky spoke of artillery beyond the ridge and the men in khaki moved with a weary order. Helena waited and then fell to the ground halfway up the slope in exhaustion so absolute she thought she might go on breathing but never move again. The white cloth in her hand—Potter’s instruction—fell from her fingers. She remembered the taste of the soup like a memory of time and closed her eyes.

The field hospital smelled of disinfectant and the same musk that builds up in places where men spend nights awake: the smell of survival. Doctors there mended more than flesh; sometimes they sorted histories into categories—enemy, friend, suspect. Captain Harris, an intelligence officer with a notebook and a face that carried more neutrals than emotions, visited her bedside. He had interviewed thousands of refugees that month. He did not expect a story like hers, and when he first heard it—“I poisoned the SS command”—he laughed with the disbelief of a man who takes narratives as if they were always fictions. But Helena gave him dates, a place, and a detail no lying mind could fabricate: the men had eaten her soup on a Sunday, the entire house present.

Harris took her seriously. It was not merely a curiosity; it was a fissure in the way the last months of the war might unfold. The British intelligence apparatus leaned forward. If the story were true, it was both a coup and a catastrophe. Within the walls of the field hospital, they treated Helena like evidence, sometimes like a living relic. Reports went up, encryption went crackling across channels, and a sealed file in London took notice. Men in offices that smelled of pipe smoke and stale coffee debated the cost. The wound was real: Posen had indeed recorded an abnormal cluster of deaths on the dates Helena gave. The Germans, as is their habit in matters of shame, had buried the contradictory facts in euphemism: illnesses, unexplained collapse. The paper trail was messy but not absent.

Yet the British did something they rarely admit in their romances about war: they chose politics over truth. The Soviets had reached into Poland’s bones and claimed the country as part of their future. The West’s officers—practical, frayed by years of pressure—worried that broadcasting the tale of a nun’s poison might become a political hot coal. The Russians might demand custody. They would interrogate anyone who had helped a saboteur. They might use the incident as propaganda to claim Western radicals had deliberately set civilians at risk. The British, newly conscious that tomorrow’s lines were being drawn not in trenches but in conference rooms, folded the file twice and labeled it top secret. They told Helena her act would have to remain hidden for the sake of peace, for the alliances being forged like brittle sugar. They called it a protective secrecy; she called it a burial.

Helena did not want fame. She refused medals like she refused to dress up for a festival she did not believe in. She was not a public actor. She was a woman who had made a choice and wanted the consequences to belong to her only. But secrecy had another cost: it muffled the world’s judgement, suppressed the moral conversation she had hoped might make the pain explainable. Instead, the town burned and the names of the two hundred lynched were written on a local plaque with no explanation beyond the word “martyrs.” The truth was a scar hidden under bandages that would not dissolve with time.

She went back to Poland by the slow, gray mercy of repatriation trains. The nation she returned to was a landscape of husks: cities leveled, churches shuttered, men in the wrong uniforms walking with the wrong accents. The Soviets were there now, their gaze as heavy as the winter. Helena found a small convent further south where sisters tried to rebuild an orphanage from the detritus of war: a cracked basin here, a pot there. She slipped into the work like a prayer. For a decade she cooked and cleaned, bathed children in water heated over a smaller flame, and mended shirts until the needle tiresome in her arthritic fingers. She never spoke of Posen in the public language of the world. She kept a small, battered diary with pages that curled like old bread, and in it she wrote in a tight, secret script: the names she could not say aloud, the faces that returned in dreams like ghosts who had come to plead.

The world changed in ways that felt whimsical to the living and monumental to the letters. Space missions and rock and roll, new borders and old grudges. The British file stayed under lock and stamp. Years passed into a decade and then two. Helena aged. Her hands became liver-spotted and knotted with arthritis. Her voice thinned. She carried the weight of what she had done with the stubbornness of someone who refuses to leave a field before the harvest is gathered.

Then, toward the end of her life, she received a visitor. Potter had somehow found the convent again years later. He was gaunter, his cheeks cut with the lines of a man who had seen too much incarceration and not enough sunlight. He had been in Soviet prisons and returned with a cough that never quite left him. They sat on a wind-broke bench and said little. Their conversation resembled the slow, careful exchange of people who had been springboards for one another’s survival once and were now archives of memory for each other.

“You did not kill the town,” he told her once, because that was what she feared—she carried the loss of the two hundred as if their faces were a permanent watermark on her soul.

He said, “You broke something. The SS in Posen began to fight among themselves after that. They were paranoid. They tested their own food. They turned inward. Because of that, Potter said, more lived than died in the months after.” He had met a survivor, he explained, who had later said as much. It was a small, brittle consolation, the kind of thing war sometimes offered those who did what history called impossible.

Helena clung to that rumor the way a drowning woman clutches for driftwood. It did not absolve her. It did, perhaps, make the ledger less solitary.

Her diaries came to light after her death. Paper has a way of speaking when tongues are still. A British clerk clearing old files in the 1990s, when the iron curtain frayed and the archives opened, found the sealed “Poznan Incident” folder and, curious, sent it on to a historian who had a taste for oddities. Dr. Tomasz Lewandowski—an academic with a neat tie and a hunger for overlooked pages—traced the handwriting, followed the paper trail, and when he found the kitchen’s foundation and the sealed tunnel beneath it, he felt a chill that was colder than stone.

The revelation detonated in the press and public conversation in ways that neither the secrecy nor the passage of years had predicted. People asked the simple, terrible questions: was she a hero? Was she a murderer? Did she commit one atrocity to stop many? The answers, as always, were bitter and partial.

In Poland, old men who had huddled while fire took their roofs came to the convent and placed flowers at the plaque that ended there. Families of the two hundred came to speak and to ask questions. Some said they wished she had not done it; some said that in a world without choices she had reached for something that made a dent in evil. The Vatican was mute for a long time, as if it feared that any word might tilt the scales unfairly. Historians argued in journals with the calm of men pruning a hedge; others argued in the squares, louder and rawer.

Helena had kept her last confession sealed in the diary she had thought would die with her. On the day her body was laid beneath a wooden cross in the conventyard, her fellow sisters placed her hand over the small leather-bound book. They read it afterward. The lines were not confessions in the way a priest expects. They were a woman’s ledger: the taste of soup, the faces, the names she could not forget. She wrote not seeking absolution but understanding. A few passages contain an attempt at theology—a wrestling with the idea that God might be present even in acts that violated scripture for the sake of a living world. She wrote, more plainly, of a certain small, fierce mercy: that she had acted to stop their certainty that they would get to live as men of honor when they had behaved like devils.

When the historian published the research, there were interviews and documentaries and a long, televised debate in which voices that had lived across ideologies fell on either side of an argument. Some called her pragmatic; some called her monstrous. A woman in a small eastern town said, on camera, through tears, that Sister Helena had saved her father’s life because the men in his town had been diverted and they were able to flee into the spring. Another elderly man, his hat in his hands, said simply, “My brother was taken that night.” No moral calculus can make both of those truths sit comfortably together.

It was not the historian nor the state nor the Vatican that offered what might be called reconciliation. It was small gestures—children in the orphanage where Helena had spent the last decades of her life coming to the square to recite a poem; a memorial event where clergy of different confessions lit candles together; a woman who had lost a son to a reprisal choosing to place a sprig of rosemary at Helena’s grave and saying, with the brittle honesty of someone who knows wounds will not close, “We both loved our children.”

Years later, Potter’s nephew—Christina’s granddaughter—arrived at the convent with a thick envelope. Inside was a letter Potter had written in the last weeks of his life. He had been unable to return after the gulag; he had survived but returned to smoke and silence. In his letter, he did not excuse or judge. He wrote of a world where decisions were made in the margins of history’s book and of the small human costs that decisions demanded. He addressed Helena as if she were still at the stove: “You took a risk that shook a terrible nest. You paid for it in ways that never needed to be paid, but the world is not tidy. It is made of torn cloth and patched rugs.”

The community that grew around the story was not a chorus singing the glory of a woman who had become a myth. It was, rather, a small and fractious assembly of people trying to tell truth without turning it into theater. Some came to curse her; some to bless her; most came because the story forced them to face what happens when ordinary moral frameworks fail to grapple with extraordinary evil. Children read history and asked questions their elders were sometimes too tired to answer. In schools, the tale became a way to talk about choice, about agency, about the cost of resistance. In some lessons, Sister Helena was a case study; in others, a tragic figure; in all, a human being.

Helena’s last days were quiet. She refused a medal when it was offered posthumously by a committee who thought renaming a library might stitch a small honor into the fabric of her anonymity. She said, once, to Potter’s nephew who insisted, “I do not want a statue. I want a name on the list of those we fed. I want the children to eat. If my life costs a loaf of bread in the autumn, then give them the bread.”

Her end, when it came, was as modest as the life she had chosen in the years after the war: a slow ebb, daughters of the convent praying at her bedside, a young sister cleaning her hands and humming a hymn she had heard once in childhood. She tried to speak—her lips moving like someone practicing a prayer—and called the kitchen “finished” with a breathless laugh that made those around her smile despite the ache. She died believing, perhaps, that she had chosen the only way she could to protect the future she loved more than herself.

History, like hunger, is often resolved in the silence between votes. People will argue forever about whether the means justified the ends. Those arguments are necessary, and their necessity is their cruelty. Yet there is another truth that rests quieter: that individuals, when seeing only ruin ahead, sometimes choose to act in ways the law cannot contain. That action will always carry a cost. That cost, too, becomes a part of the story we tell.

In a small square in the town that had known both flames and gardens since Posen became Poznań again, there is a plaque that tells a truncated truth: names of two hundred lost, dates marked, an acknowledgment that those who acted in war left painful legacies. Nearby, in the library that once was a convent kitchen, someone placed, decades later, a small pot of thyme as an offering. It is not a monument; it is a smell and a memory and the insistence that something human remains.

People come to stand there, to think, to argue, to kneel, to laugh in the mild, strange way people laugh to keep grief from overtaking them. They talk now of accountability and memory and the ethics of resistance. Young parents bring children and, sometimes, ask the older women who remember to tell the story in a voice that is not a sermon. Those elders, in their time, all end with the same line: “She fed the hungry. She tried to stop the terrible ones. She paid for it.”

The final words in Helena’s journal are not those of a triumphant conqueror or a broken martyr. They are quieter. She writes, in a slow spidery hand, toward the end: “I do not ask for absolution from men I have not wronged. I ask only that those who come after me look hard at the small choices. See what they do. If you must choose, do it knowing the bones that will carry the weight. Do it for love.”

It is an instruction neither simple nor kind. It is human.

Years later, when tourists take photographs of the old stone building and the library windows that still fog with the scent of old books, an occasional whisper passes: once, a nun served a soup that changed the course of a town’s fate. People who know the full story think of the woman in the kitchen and the faces she could not wash from memory. They argue in cafes and on benches and in classrooms. The debate will never end, but in some small ways the place has healed: a plaque stands, children’s laughter drifts down lanes, and in the early March mornings—if you stand in the lane that runs behind the old library—you can sometimes, if you are very still, smell the faint ghost of vegetable soup, warm and unremarkable, and remember that at the heart of history there are always hands stirring a pot, and people listening for the sound of those spoons.

News

STEPHEN COLBERT NAMES 25 HOLLYWOOD FIGURES IN A ‘SPECIAL INDICTMENT REPORT’ — A WEEKEND BOMB THAT SHOOK AMERICA.”

The 14-Minute Broadcast That Exploded Across the Nation It was supposed to be an ordinary weekend.A quiet Saturday night, a…

On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does not simply revisit the story of Virginia Giuffre. It tears apart the entire network of power that once fought to erase that truth from history.

“On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does…

THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE OF VIRGINIA GIUFFRE

“THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE…

They tried to bury her. She left a bomb behind.o press tour. No staged interviews. Just 400 sealed pages… and the names no one else dared to print. Virginia Giuffre — the survivor, the fighter, the woman whose truth once disrupted palaces, gyms, and studios.

Now, even after her death, Virginia Giuffre’s 400-page memoir is set to reveal the hidden battles, the names, and the…

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed before the world finally uncovered the truth..

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed…

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway I was paying for.

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway…

End of content

No more pages to load