“Wake, sister,” I whispered at Celia’s doorway. Her eyelids fluttered. She took me in—the dirt under my nails, my shawl, the way my shoulders carried their own story—and sat up with the smallness of someone who has learned to measure all risks against the life of her child.

“What is it, Patience?” she breathed, already afraid this meant bad news.

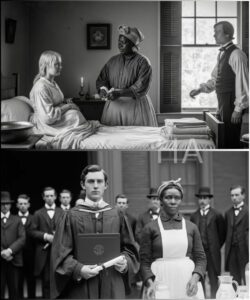

I eased the Whitmore infant in under the blanket and let Celia touch the soft hair. Her fingers trembled.

“What if I told you there was a way,” I said, “to change what your boy’s life will be?”

She laughed once, a brittle sound. “Change how? He’s born a slave. That’s done.”

“Not if someone else raises him as a Whitmore. Not if another child grows up carrying his name in the big house.”

She stared at me as if I had set the sky on fire. “Are you mad?”

Madness has different accents. Mine sounded like a slow, steady plan.

“Think,” I said. “You’ve seen what they do. Your last two were sold to traders because master’s blood ran through them and he refused to own them. Give him this son—let him have the ease and the education. Let your son eat when he is hungry, learn when he wants. I’ll put their baby with you. They won’t be able to tell.”

She swallowed against the ache of that idea. “They’ll kill you. They’ll kill both of us if they find out.”

“And if they find out,” I said honestly, “it will be the kind of spectacle that makes a lot of men feel like the law must be enforced twice as hard so no one thinks to imitate it. But if we are careful, if we choose the right nights, the right windows, we might breed a different kind of argument into the world.”

She looked down at her boy sleeping—the even rise and fall of his chest—and then at the Whitmore infant. A mother’s math does not always add up in ways logic would approve of; it counts love and possibility. Celia reached for the child and kissed his forehead.

“Promise me one thing,” she said. “If you do this, find a way to tell me. Tell me how he’s growing. Tell me if he’s kind.”

I did promise. I promised with the certainty of someone who had nothing left to lose but time and secrets.

That was the first switch. The second came half a year later at Bogard plantation, on a storm-lashed night when both Mrs. Bogard and a field woman named Grace went into labor. The rain drummed like a chorus and covered all tracks. Grace, who’d been stripped of two children to traders before, did not ask twice. That night, a pale baby with hair like a hunter’s gold was handed upwards and a life was exchanged beneath thunder.

I did not act from a place of simple revenge; it was more subtle and more urgent. I had seen enough to know that whiteness in this place bought sanctuaries and book-learning and an assurance of bread. I had seen black babes sold off as market goods. I wanted to pull the thread taut enough that the fabric of the lie would reveal itself.

So I made another promise: not to save every child (there were too many), but to create—where I could—paradoxes that would question what we had been taught. If the masters could claim power by birthright, I would, in small, dangerous ways, redistribute that birthright.

For twenty years I repeated that pattern. I recruited a few trusted souls who knew how to keep a secret because the keeping of secrets had always been a part of surviving the plantation economy: Mary Ruth, who worked in the Caldwell house and could ensure doors were left unlocked at opportune moments; Old Moses, who ran messages through the fields and knew how to make a rumor move like a wind; Samuel, the stable hand who could arrange a broken wheel at a critical hour. They each had their reasons. Some had lost blood to the traders. Some had children they wanted saved from the ledger. I paid them in the only currency I had—loyalty, information, a share in the plan, and, when I could manage it, a coin slipped in a palm.

We grew bolder. We learned to tell stories that would cover our steps: a dead sister who had left an orphan no one remembered; a baby born with jaundice whose skin would “lighten” as it matured; a child marked with a birthmark that could be explained away as an oddity. We used the rhythms of plantation life—funerals, harvest panic, drunken overseers—to hide our work in plain sight.

Sometimes the switches were partial. Twins complicated everything. I could not always find two children to trade in matched pairs. Once, when Mrs. Harrison delivered twin boys and Rebecca in the quarters had twins of her own—one light, one dark—I took only one of the Harrison twins and swapped him with Rebecca’s pale son. The family swallowed the explanation that one of the twins had been premature and would “normalize” as he grew. Rebecca accepted a story about an orphaned child taken in because she was poor and alone. The human heart is a fierce apologist when it asks nothing.

There were triumphs that glowed like hidden coins. Black children raised in books and parlors became lawyers, physicians, planters; they spoke with the cadences of the men who’d bought their freedom with money or with promises. Many drank of the same prejudices they’d been taught—their minds shaped by tutors and their social circles—until the sight of another black man in a uniform startled them like a mirror that did not fit.

That was the horror and the heartbreak of what I did. The experiment—if it must have a name—proved terrible things: environment carves the person as easily as the weather carves the shoreline; privilege begets arrogance; suffering breeds caution. I watched men who were black by blood and white by upbringing defend the very architecture that would have destroyed them had the true ledger been known. It made me sick sometimes. In the privacy of the privy, I vomited until my head felt hollow.

There were casualties. Not every switch succeeded. A few of the white children we placed in the quarters withstood the conditions poorly. Tuberculosis and dysentery took some of them young; others were sold deeper into the South and vanished into the trader’s net. I carry those deaths like thorns. They were the cost of the study I had begun between two births on a humid night.

The Civil War rattled every branch of the experiment. Masters and overseers marched off in uniforms or into court battles, the plantations were left to women or to men with raw, new hatreds. Some of my raised-as-white children enlisted for the Confederacy—how many of them were prepared to die for a cause that would have enslaved their true kin? I remembered Thomas Whitmore—Celia’s boy raised as an heir—dress himself in grey and march away with that swagger that had always made me worry for his soul. Meanwhile the actual Thomas Whitmore, the child of the master placed in the quarters as Samuel, learned to hide in shadows and cultive small, quiet rebellions.

The war ended and then began again in a different way: Reconstruction, riots, the slow, bleak maneuvers of a society that could not let go of both its money and its myths. I grew old. My hands knotted with arthritis; my breath came raspy. I kept writing because the ledger of the human heart needed to be written down if anyone was to believe me after I was gone. I kept a journal—leather, thick, bound in a skin like the skin of the world we lived in—where I recorded names, birthmarks, dates, the minutiae that would prove the impossibility and the truth.

Sometimes I wanted to burn it. Sometimes I wanted to hand it to every magistrate in Georgia and every preacher in the pulpit and listen to the world rearrange itself. The ledger was a dangerous thing: it could unmake marriages and inheritances; it could sap a man’s pride and ruin a family. I understood the magnitude of what I carried. I also understood the moral calculus that had birthed it: a life traded for a life, a brutal leveler met with a quieter, cunning justice.

You cannot live many years making the same choice without understanding that choice’s shape. I had thought at twenty and thirty that one act could change the world; by sixty I knew that one act could only rearrange its pieces. But rearranged pieces pile up in time into a different order.

The most devastating fruit of my labor was Thomas, who became a man of stature and influence and eloquence. I watched him accept honors as if they were the natural gift of the heavens. At his graduation from the University of Georgia—how odd to see a Black man in mortarboard and sash among those who had once considered him property—I sat in the shadows and watched his face, carved like a man who had never doubted his superiority. He spoke at commencement on the natural order of things, on the duty of white men to shape the world. His words fell from a man who spoke the language of those who’d nurtured him, but they hurt because I knew the truth behind his forehead.

The irony is a heavy stone. Thomas—Celia’s son—rose as a white man in every way the world measured: education, speech, and pedigree. Meanwhile Samuel—the man who was born as a Whitmore and reared in the quarters—sweated in the fields until his face weathered like an old fence and his posture recalled the bending of someone made to carry more weight than he ever should.

There were moments that surprised me with their tenderness. Margaret—Grace’s daughter who grew up as Margaret Bogard—once slipped from her carriage and into a low street where she found her biological mother bending over a wash tub. Grace curtsied and Margaret directed her servant to bring more water. It might have been any exchange. But once the story came to light, and Margaret learned what she actually was—no longer the white lady of blue-blood gossip but a woman whose lineage belonged to a line of washerwomen—she crumpled in a way that would make the heart ache. For weeks she could not leave the house.

The one time I almost told her the truth before it all spilled open I sat in the parlor of another woman’s estate and watched the steam rise from tea. “You speak as if you have seen too much,” she said, surprised when I spoke of the fragility of human identity.

“I have seen a child change with a pocket of bread,” I said. “I have seen a child taught to hate the very blood that runs through her veins.”

“You dramatize,” she said.

We all dramatize sometimes. I kept my mouth shut, learned to be patient. That patience—my namesake—was both my armor and my torment.

When I was seventy and the weight of memory pressed me to bed, I knew that the secret could not die with me. The journal had grown too heavy, the ledger of human lives too detailed to vanish like an old, disbelieved letter. There were men and women who would change the world if they knew their true parentage: Thomas, who might become an ally; Margaret, who might be taught to care for those her class had once despised; the Harrison twins, one who argued for separation and one who argued for equality. The truth could be a scalpel or an ax; I did not know which it would be.

William Morrison came to my cabin because he wanted stories. He was younger than I had expected—an earnest man with a notebook and an earnestness that makes some who have survived the world distrust him and some want to trust him. He asked me what slavery had done to the souls of both the enslaved and the enslavers. He was a reader from the North and had the curious eyes of a man who thinks that knowledge might yet steer the ship.

“I have done something,” I told him one evening, mostly to see how his face would arrange itself around the words. “Something I think might prove that race is a construct more than a fact.”

He leaned forward. “What do you mean?”

So I told him, in words that could fit in the palm of his hand but with implications that made his breath catch. I told him about nights and rain and lullabies traded like contraband. I told him names—small, fatal things: Thomas Whitmore, Margaret Bogard, the Harrison twins. I told him I had a journal that recorded every swap I had made.

He did not believe easily; perhaps he was too honest a man for such a thing. He asked for proof and I gave him the ledger. He read as if reading a Bible, and his face grew pale and then hard.

“Why?” he asked finally. “Why risk this?”

“To show,” I said simply, “that what you call natural is often taught. That a child taught to hold a book and fed soft bread will learn to speak in the tongues of power; a child fed on rejection, beaten and kept, will learn humility the way a plant learns to bend. I wanted to see which would be truer: the skin or the upbringing.”

He nodded, too young to be entirely sure of what he heard but old enough to understand its reverberations. “This will topple things,” he said.

“It should topple things,” I said.

I did not live to see the whole of the reckoning. I died in the small hours of a cold February morning in 1880. Morrison promised to publish. He kept his promise. His book—The Midwife’s Secret—hit the presses with a force I had only glimpsed in the fury of a storm. It unfolded like a map: the ledger of names and dates proved too precise to shrug off as a fabrication. Families were forced to look at photographs, to compare birthmarks, to talk to old servants who recalled nights and names; courts opened, and at the center of every hearing someone told the tale of a child handed over or taken away.

The aftermath was not neat. It could not be. Lives are not tidy when they are overturned. Some men lost their positions; some families fell into despair. In a courthouse in Atlanta a man named Thomas Whitmore—my boy—sat with his chin in his hands as a physician pointed out the exact crescent-shaped birthmark behind his left ear, the one I had noted in the ledger. He laughed until he did not. His laughter became a scream that tore everything apart.

Thomas had a nervous break. He read speeches from his bed for a while and then, slowly as water shapes a stone, he began to move. He used the wealth he had to reach backward; he hired teachers for children in the quarters, built a small school on a plot his grandfather had once bought with the sweat of others. He took to the platform not with the venom of his earlier speeches but with the contrition of a man who had been given a chance at knowledge and found his own ignorance more horrible than his critics had ever said.

Margaret withdrew. She could not reconcile the tenderness she felt toward her mother—the washerwoman—with the system of measuring worth she’d grown to value. She sank into silence and refused visitors for months. Eventually, Grace and Margaret met in private. Margaret pressed her forehead to Grace’s hair and cried as if grief could purge the past. Grace forgave slowly; forgiveness is a long job with no set hours. They built a relationship that pleased neither of them and both of them: a fragile, mortal thing that asked for nothing grand, only the right to be called mother and daughter.

Some lawsuits were ugly. Courtrooms are not sanctuaries; they often function like scales tipped by money. The Georgia Supreme Court had to rule on inheritance, and it did so with a sternness that asked whether law followed blood or upbringing. It opted for biology. The decision set a precedent: legal ties followed the body as much as the cradle.

Those who were the victims of my swaps—those white children raised in bondage who had been deprived of education and comfort—could not be made whole. Compensation was labyrinthine and insufficient. Money of this world cannot buy back a childhood. We tried to help them; we failed often, and that failure rests in my throat like a shard I will never dislodge.

Yet there were small triumphs. A handful of the raised-as-white turned their education toward the cause of justice: lawyers took cases pro bono, schools opened—some funded by disgraced heirs who chose to use their guilt as something other than a cloak. The Harrison twins—James and Robert—faced one another in hearings, the seam of their lives pulled taut. They argued, then reconciled, and went on to create a small plan that would change the way work was done on their acres. James, in a later life, became a slow convert to equality, perhaps understanding finally how absurdly narrow his former certainties had been when viewed through the burrowed lens of fact.

I do not tell the story because I want you to call me hero. I do not want absolution. There is blood on my hands: the hands that switched babies are the hands that might have given some children hardship. I confess this plainly. But I also knew that the world in which I lived did not offer half measures. It offered a ledger you could not change by law, only by lives.

In the end, the ledger I kept did what I hoped a ledger might do: it forced people to ask questions they had previously refused to consider. If the line between races could be so casually breached by a midwife in a thunderstorm, what did that say about the claims of natural order? If nurture could shape the man, what moral imperative did that create to expand nurture? If a child raised with books becomes eloquent and a child raised under the lash becomes stooped and silent, then it is cruel to pretend those things are given by God and not by circumstance.

I died with a hope, and I died with fear. The hope was that some small victories—schools made, children taught, households shamed into reflection—would outlive the ugliness I had begun. The fear was that the waves of reaction would wash back and entrench what had been uprooted. The truth has a razor’s edge: it can cut and heal with equal measure.

Years after my bones had returned to the thin soil beside the river, people still debated me. They turned my story into songs and sermons and an academic case in universities. Northern newspapers printed verses that called me a heroine; southern papers called me a monster. Between those two taut descriptions lay the complexity of everything human: love and desperation, ingenuity and cruelty, the bright small courage of a woman who had nursed a plan and the moral confusion that plan birthed.

If there is a final line to tie up such a life, it is this: the world is too large and too small at once. One person’s act cannot dismantle an empire, but one act can make a gap in the empire’s foundation that, later, others might widen. I did not set out to break families. I set out to show what the world might look like if one set of rules – the rule that told men by the color of their skin who they were allowed to be – was not the only thing shaping a life.

I was Patience the midwife, and I used the smallest of miracles—the cry of a newborn, the rustle of a blanket—to argue for a better world. I failed and I succeeded. I hurt and I healed. That is the shape of what is human.

If you have any mercy in your heart, give it to the children who grew up under the wrong names. Give it to the mothers who stood in wash houses and parlors and curtsied to their own daughters. Give it to the men who stood on stages and learned to hate, then learned to change. Give it to the thing I could not give myself: the chance to be forgiven, not for the deception, but for choosing, however clumsily, to make the scale tip in the direction of chance.

When the ledger was opened to the world, men overturned altars in their minds. They learned to ask questions and, sometimes, to answer them. That will have to be enough for me. If any of the children we switched live on in your family’s tales, tell them that the name they carry might not be the only truth about them. Tell them that a woman in an old cabin once believed a terrible thought and acted on it believing the world would be better for it.

Tell them, if you can, that in a place built on the certainty of skin, a small, stubborn human dared to believe in the power of nurture—and in that belief, warped and flawed, found something like love.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load