Most of the repair line had been instructed by rule books and supervisors to treat the visible failures. Overheating? Radiator service. Turret jammed? Lubricate and tighten. Engine dying? Replace the faulty part and send the tank back. Eli listened to this chorus and took a slow breath. He did not begin by wrenching bolts. He took out his notebook and wrote Return Number Four, Engine plus Turret plus Heat, Heavy on Hill, underlined three times. He walked to the rear, opened the access panels and traced cable routes with a patient eye. The radio had been installed and then shoved into existence; the cables had been routed down a shorter path to save time. Time, in the war, was often the commodity that commanded choices. The trade-off—shorter cable runs, a few less brackets—did not show up on a checklist. It showed up in flexing under torque, in wires tugging at junction blocks when the engine shifted, in the turret drawing a little more strain than the mounts were intended to bear. A string of small injustices against the machine had, cumulatively, created a monster that coughed when asked to climb.

He told the supervisor that replacing worn mounts would be proper by the book, but it would only postpone the next collapse. The supervisor looked at his charts and shrugged. “We’re behind schedule,” he said. “We don’t have time to reroute every cable someone installed wrong.” Rules made work transferrable. They made soldiers feel safe. But rules did not hold up in bog and shellfire. Eli asked for permission to do more. The supervisor gave it with a weary caveat: fix it fast, and if it breaks worse it’s on you. Eli did not reply. He set to work like a man starting a conversation with metal.

He used parts salvaged from another machine — mounts matched carefully, not plucked at random — and then he rerouted the cable runs to give slack where there had been tension, to shield vulnerable junctions from abrasion where metal flexed in the hull. He added a brace in the engine bay to stiffen a section that had been wobbling like a loose tooth. He could do none of these things with a neat blue-stamped approval, and none of them were in a factory drawing. They were, instead, the kind of adjustments you make when a tool has to serve a story it was never told to tell. When he closed the panels and called the crew to test it on the hill that had haunted them, they grumbled. They wanted certainty. He gave them a dare. “Take it up that hill,” he said. “Traverse the turret while you’re at it. Run the engine. Try to break it.”

They tried. The Sherman climbed the slope, the engine note evened out into something like contentment. The turret rotated without the previous complaint of a wire being tugged like a throat. The heat crept up as it ought to and then settled. The crew drove back with a new, careful silence. Not triumph. Not reverence. Just the kind of relief that people feel when a routine danger becomes ordinary again.

That was not the end. A single success can be written off as luck. Eli watched other Shermans arrive with familiar complaints: overheating that came and went, electrical oddities when the turret moved on rough ground, a shudder that began in the back and worked its way through to the gunner’s hands. He began to see the same hidden skeleton in each case. Someone had taken a shortcut, not maliciously but for the sake of speed. Someone had assumed factory tolerances were enough forever. Eli began doing the same kinds of modest, patient changes. Not identical procedures — no field technique can be slavish — but the same approach: understand what the tank actually endured, protect the points that took the brunt, add small reinforcements where the life of the vehicle demanded more than the factory had imagined.

Word spread at the speed of gossip and hunger. Crews began to ask that their downed tanks be sent to Eli’s bay. They did not do it because they admired his notes or wanted to read his diagrams; they did it because when you live inside a steel box you learn quickly which people lower the odds of dying. Mechanics sneered at him sometimes. Field doctrine preferred uniform work. The army liked templates; they made training and logistics simple and the world less likely to break down because somebody decided to experiment. But reality is a street with potholes, and sometimes the manual is a map drawn for a summer day. Eli’s notebooks, small and stained, began to look like a different kind of map — one that showed not where things should be but where they would actually get you through.

He wrote everything down. Grease-stained pages filled with shorthand sketches: cable here, brace there, note about flex at the joint. He sent a few of his notes up the chain with the same modesty he used to speak — not as doctrine but as observation. The bureaucracy answered, when it answered at all, with a polite chill: repairs outside approved procedure are not recommended. But the small ripples of Eli’s tinkering could not be halted by a memo. One of the maintenance officers, looking at a chart months later, saw that a serial number that had returned with alarming regularity had suddenly stopped in its pattern of failure. He asked the repair line who had been responsible. The supervisor muttered, “One of my mechanics spent more time than usual on it, changed mounts, rerouted cables, added reinforcement. Not by the book. Did it work? Yes.” The officer made a note: observe this man’s methods. That paper would not become a plaque, but it opened a small door through which the ideas that had been scribbled in grease could begin to go farther than a single bay.

What transformed Eli Turner’s reputation from mere eccentricity to a quiet kind of legend was not the tanks he fixed but what those tanks were able to do afterwards. The cursed Sherman with Briggs’ fists and the crew’s suspicious glances went back into a muddy valley on a mission that could have found it in pieces. The slope that used to make its engine cough now found it steady. When orders came to halt on a slope and traverse the turret, the gunner was not thrown about by a sudden lurch. Heat climbed and steadied instead of spiking and plummeting. In a series of engagements where infantry had expected only shaky armored support, the Sherman held position, moved when ordered, took hits and returned with its crew — sometimes battered, sometimes quiet, sometimes telling jokes about the cursed machine being only cursed at the enemy now. Men who had never known Eli came to know his work in the substitution he made for luck: steadier tanks, more predictable behavior, fewer brutal surprises.

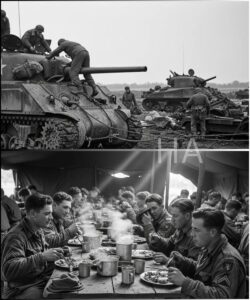

War has a curious appetite for small triumphs. Headlines demand spectacle, but campaigns are decided in the grind between trucks and railheads, in the way fuel arrives and in which engines keep rolling. The Sherman’s reputation as an engineering legend did not begin with a single grand redesign. It crept out of thousands of tiny decisions made by men like Eli. German tanks in the early years could be breathtaking in their engineering audacity, but breathtaking things often need attention. The American approach, famously, asked a different question: can we make something that still works when parts are missing, when the maintenance has to be done by tired hands in a field where the sun never quite shines? Eli’s work exemplified that. He did not craft a perfect machine. He made existing machines less delicate. There is a difference between brilliance meant to astonish and pragmatism meant to serve. Eli practiced the latter, and it had something like a moral valence to it: when a machine fails less, men live a bit longer.

As the war bunched seasons into urgency, the repair lines became a theater of improvisation. Eli was a quiet director in a place that never held an audience. Young mechanics apprenticed to him, not because he taught them to break rules but because he taught them to listen. “Put your hand here,” he would say, and feel a slight twist that told him where a metal frame was crying. He would make a small bracket at a deliberate angle and say, “This one takes a little more work now, but you’ll spend less time on it next week.” The apprentice would shrug and then, in a few days, not shrug at all because the tank that had snapped bolts every other day now lived peacefully. The apprentices learned a practical philosophy: observe, interpret, adapt, refine, document. It sounded like engineering, and it was. It looked like tradesmanship, and it was. It was human work dressed in throttle and weld.

When the war ended, machines were reassigned, scrapped, or melted into something new. Entire priorities shifted back from survival to comfort and production. Eli went home to a civilian life that was softer in texture but equivalent in complexity. Tractors replaced Shermans, the clients were farmers and company foremen instead of captains and crew. He kept his notebook. It still bore the spills that marked decades. Its pages were not blueprints for glory but incremental design: notes to remember that in the wild, actual conditions matter more than optimistic labels. Veterans who drifted through his garage sometimes left a lighter step. They would sit at the counter and remember the man with the greasy hands who had been called mad because he insisted on thinking one layer deeper. “He made the tank mad at the enemy, not at us,” one of them had said once, and the phrase stuck like a good proverb.

Eli’s legacy did not wear a name on a museum plaque. It lived in manuals rewritten slowly in peacetime, in new appendices that recommended checking cable runs where previous drawings had left them exposed, in a small footnote on training regimens: check for flex at this joint, protect cable runs in this area. It lived in the comfortable confidence a young mechanic felt when he remembered to add a little reinforcement before sending a vehicle back. It lived, most importantly, in lives extended by minutes that became hours and in tanks that returned, battered and useful, rather than burning and final.

There are, in every institutional story, people who do the work that neat histories fail to narrate with chorus and trumpets. They are the ones who notice the way a joint moves just before it snaps, who ask what a machine does when it’s tired and who make space to fix the reason it’s tired, not only the symptom it shows today. Eli Turner was one of them. He preferred the company of pistons to parades, and his sense of duty was not a slogan but a habit: refuse to accept fragility as destiny.

Years later, an older mechanic might be found sitting on a wooden crate outside a shop, the sun finding grooves in a face that once bent low over tanks, and a boy with grease on his cheeks might ask to see the famous notebook. Eli would pull it out with a show of reluctance and hand over a page. There, in cramped scrawl, would be a sketch and a note: Bad cable path, hill brace here. Factory design ok for parade ground, not for this road. The boy would look up and ask why he had written such small, humble things. “Important when that was all we had,” Eli would say, in a voice that had seen too many roads. “Now it’s just how I know to look at machines.” He would fold the notebook carefully and hand it back, as if the passing of such knowledge were not a triumph but the only civilized thing to do.

Eli never sought credit. In a world that stamps medals and listens to speeches, he kept a different ledger: a list of machines that had not failed where failure would have been fatal, people who had returned from a mission, a cup of coffee shared in a tent after a day that had preserved more lives than the men who received the medals would ever know. If the Sherman became known as an engineering legend, it was not simply because of factory floor choices but because thousands of small hands made it behave when the world demanded it. Eli was not an exception. He was a node in a network of careful improvisation that stretched from production line to field repair to the men who drove and fought in those machines. That network, noisy and human, is what keeps armies moving and towns buzzing.

Mad Eli, as some soldiers had called him, was only mad in the sense that he refused to accept the usual. He treated a manual as a starting point, not a liturgy. He believed that thinking a layer deeper — asking how the machinery responded to heat, slope, and the cruelty of reality — was not luxury but responsibility. He could have said the same words with less simplicity and called them engineering theory. But his was a practical creeds that fit in a notebook and a toolbox: when you make things a little less fragile, you make people live a little longer.

When the last page of Eli’s notebook grew too thin to take another note, someone took it and preserved it not for fame but because it was useful. A young mechanic, years later, would find in the scribbles a practical solution to a problem that had turned up again. The bracket, the extra slack, the careful match of parts — these small things traveled forward. The men who owed their lives to the steadiness of an altered Sherman would not march in parades for Eli; they filed into civvy life, planted crops, worked in factories, and raised children who learned the value of practical care in smaller, more domestic forms. Eli never changed the course of the war single-handedly. He altered a curve, a reliability curve that, aggregated across thousands of machines and the men inside them, made supply lines possible, advances sustainable, and retreats less catastrophic.

In the end, what makes someone an engineering legend is not only the novelty of an invention but the stubborn humility of repeated, effective improvement. Eli Turner’s legend was quiet because his victories were small and persistent. He stood, where the world often values the spectacular, with a torch that lit the hidden joints and the places that flex. He believed that the human cost of mechanical failure was never abstract. Machines that fail in neat, testable labs fail differently in mud and under flak. The small adjustments that respect that difference are the kind of bravery that does not need a band to confirm its value. It needs only someone willing to look, to listen, and to make the work of living slightly easier.

There is a dignity in that — not the dignity of monuments but the dignity of mundane, attentive labor. Eli lived it. When he died, years after the war had ended and the world had recycled its iron into new shapes, there were no headlines. There were, however, men who stopped by his funeral who had served in tanks that had learned to breathe differently under strain. They stood at the edge of his grave with their hands folded and their coats buttoned tight against a wind that carried something like the smell of old oil and summer fields. They remembered, in small fragments: a slope that did not kill, a gun that did not jam, a night that ended without blood for reasons they could not name but that saved them all the same. They carried his notebook home, or his methods, or the memory of being taught to listen to an engine like a story. That, in the end, was the legacy: not recognition, but usefulness; not glory, but lives extended by minutes that mattered.

Mad? Perhaps in another language, in a different tale, his insistence on seeing one more layer would have been called something slicker: insight, applied science, the art of robustness. But for Eli, the name did not matter. He had a toolbox, a notebook, and a sense that a machine that does not break means fewer funerals. He did the work because it was the right thing at the right scale. Sometimes history remembers men by the grand gestures they make. Sometimes history owes its victories to quieter people who simply will not accept fragility as destiny. Eli Turner belonged to the latter. His hands kept engines turning and men returning. The Sherman became an engineering legend not because it was flawless, but because it was resilient — and resilience, above all, is a human accomplishment built not by one mind but by many patient, stubborn hands that fix things so others can keep going.

News

End of content

No more pages to load