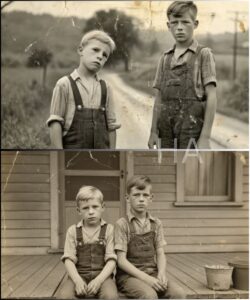

But the Lawson boys did not forget, and neither did the earth they’d been found on.

Needless to say, nothing in the Lawson house ever felt entirely safe again. After the boys came back, there were fissures in normalcy as neat and deliberate as the grooves in a carpenter’s dovetail. James drew circles in the margins of his schoolbooks. They were neat, not the ropy scrawl of a child but the concentric patience of someone tracing an outline he recognized. Robert stopped joining the kids at the creek and stood at the fence-line listening as if a conversation of insects and wind needed attendance. They did not speak of the eight days; they did not have to. Their silence hummed with answers.

Arthur tried to make the quiet normal—he repaired the porch, adjusted the hinge in the pantry, took extra care with the wood he smoothed, but sleep came in small, warning shards. The oldest Lawson—Arthur’s father, Charlie—had been the axis everyone turned away from. The massacre in the tobacco barn had left a crater in the family’s ledger, one written in blood and secrecy. The newspapers shuffled their copies and wrote of “a man who snapped,” which was easier for townsfolk to digest than “a man who bargained.”

People who have been raised in the folds of a story learn the art of containment. Arthur believed in work, in the sturdiness of oak and the metabolism of saw dust for keeping grief honest. He was also a father, and every habit of fatherhood is a small, frantic plan against the world’s appetite for taking what is ours. He began to go to places men weren’t supposed to walk—past the old logging roads, past the spots where scrub had sewn itself shut—and he began speaking to women like Aunt Celia.

Aunt Celia smelled like sage and iron. She had hair the color of smoke and hands that knew the anatomy of roots and bones. You could see in her face the long memory of a country that had been here before the rail line, before the white clapboard churches, before the names that now dotted county records. People crossed the street when she passed. She was a piece of history—someone who had been allowed to grow old without being taken apart by the town’s younger hunger for gossip. Arthur didn’t ask; he simply went. Men like him learn that there are some debts you cannot pay with coin and that sometimes the thing you need to buy is a story told the right way.

Aunt Celia spoke plainly. She told him about the stone ring that had been in the valley before settlers wrote deeds. She told him it is foolish to imagine that the ground is impersonal. The earth remembers. She said that what you call bargaining is only a thin exchange; contracts made in panic do not stop with the panic’s end. They loop and expand and demand service in kind until someone is left holding the bill that reads like a name: Lawson.

“She told my father,” Arthur told her, “and he…” The memory caught him like a hooked fish. He could not finish. Charlie had stood in the tobacco barn one Christmas and done something that kept the Lawson family on the edges of speech for decades. Arthur had never known what his father meant when he said he had been changed. He thought he could survive the silence by making sure his sons went to school, did their chores, and learned how to drive a tractor before they learned to drink. He had been wrong.

“You must understand,” Aunt Celia said, rocking on her porch like a metronome. “Things likes to be acknowledged. You feed a thing by calling its name or leaving food and, worst of all, by telling its story through the bones of your house. Your daddy thought money was a language it could understand. Some things want lineage.”

Arthur left with a bag of oddments: iron filings, a pinch of coarse salt, a lock of hair braided and tied with a scrap of red cloth. He walked back toward the valley with a new understanding of what a promise looked like when written on a man’s body. That promise collected in him in grief and growing dull with time. He waited for a new moon because Aunt Celia said ceremonies that want to be done properly will always choose a dark for themselves.

On the morning he took the bag into the woods, the clearing was quieter than memory allowed. It was a place that cleanly refused the adjacency of life: no moss, no sap, just trodden earth as pale as bone. In the center, the ring of stone rose like a small tomb, black with old age. When he stepped into that hollow, his boots sank in the echo of other footfalls. And then he saw them—two small, shallow prints, side by side, as if a pair of children had been placed there and never struggled.

Arthur spoke the truth loud enough to make his own throat ache: he admitted that his father had known and that he had been bound into a contract he could not fully name. He said he had nothing to give but the truth of his own life. “Take me,” he said aloud, “but leave them.”

What answered him was an absence of air. The world contracted in a way that made his teeth sing. He did not see it in any complete human sense. It was like looking at a mirage of a man—a tall, thin impression wearing human clothing that was almost but not quite right. At angles, it wore his father’s face as one might wear a borrowed coat. Arthur felt his skin become a thing that could be observed by someone else for the first time. There was a negotiation that felt like a trade: yourself for theirs.

When he woke the next morning, he was older by a slant of hair and a limp that told him he had been used as a hinge. His throat held an accent of silence that sometimes made his words smaller and slower. The boys’ faces—slowly, like color returning to a photograph—lost the stretched geometry of something that had been kept away from daylight for too long. Their drawings stopped. The fence no longer had a fixed listener. The town exhaled and called it a miracle.

But everything Arthur had laid upon that cold center had been paid in a different currency than his life. A debt had been discharged and rechanneled; his father’s bargain had been closed in the way only a Lawson could close something given a cut of blood. Arthur carried on. He aged as a man whose ribs had given up an internal space. He walked the property line at dusk as if his listening could keep the dark polite. He watched his sons grow. He thought, sometimes, that the ledger was cleared.

And yet the ledger is a stubborn thing. At times, James would catch sight of a slant of shadow where there should be none, and it would sting with a memory that was not quite his. Robert woke from dreams of hands with too many fingers and sometimes found himself humming a tune only a dead grandmother had ever sung. They married. They left the county occasionally. They returned occasionally. Time, patient as any tooth, ate the edge off the story until it became easier to say the boys had been lost and found, and leave it so.

Years will fold a horror into a family like a map into a pocket. It becomes folded more than read; its creases become habit. James and Robert took flights of normality that made the town proud. James, once a lanky boy who could coax a stubborn engine into life with the persuasive patience of someone born to hands, became a mechanic in a town with fewer mechanics than soot. Robert, who had once listened at fences with a posture that made the birds nervous, became a teacher in a school with low windows and small desks; he taught cursive to children whose parents would not carry the Lawson name.

There is a secret in small towns, something like a reluctance to admit the world is stranger than their yardlines show. People draw circles around stories and label them folklore. They hold their breath when old events are mentioned and swallow them like medicine. The Lawsons learned how to be careful. They learned to be ordinary with the assiduous fervor of men who had once been hollow.

Arthur died in his workshop, tools in his hands, as if he’d finally put down a weight he had borne without complaint. The funeral was ordinary, filled with neighbors who had known him since the days when his hair still had color. James and Robert attended because that is what sons do. They stood together at the casket, and for a second, a fragment of something brushed James—a phrase like cold air, the edges of a dawn. Then it slid away like a boat passing behind fog. Some memories intrude and then retreat.

After Arthur’s death, the valley pressed at James in dreams. The clearing which had been their deliverance and their prison was a small red thread he could not stop pulling. There came a time when age and the itch of lineage coalesced into curiosity, into a desire to see if a wound had actually scarred. Men like James want proof because humans are, at base, a species of tidy conclusions. You cannot tidy a wound like that without opening it. He went back.

Arthur had left him a map in the way that men leave maps: a memory of a path no longer visible to the untrained eye, an old log road that existed only on the periphery of a topographic map, a stubble of stone poking like a bad tooth. He found the clearing on an evening when the air tasted like snapped string. The structure in the center had sunk itself into the earth as if acknowledging its age. A carpet of moss had sucked at the stone and claimed it as belonging.

James stood on the periphery and felt the world sharp again. It was like an instrument tuning. He remembered his father’s words: the truth, not the bargain. He remembered a small circle of ash and iron filings, the smell of metal on the tongue. He felt very, very small. And somewhere down below, he heard it—the singing that had once been the lullaby of his abduction, the sound of someone calling him home with a voice that was not a voice at all. It threaded the trees like a song you half-remember of someone you loved.

This time he came with different intent than Arthur. Arthur had offered and bled to seal a bargain’s end. James did not come to bargain or pay. He came as a descendant who wanted to look the ledger in the face. He brought no ash, no lock of hair, nothing but a man’s curiosity and a pocket of regrets.

When he stepped into the clearing, the world contracted as it had once done for Arthur. The thing—that word seemed too human for what stood at the edge of his sight—moved in flares of possibility, wearing men like costumes. James could see the way it tried them on, how it stitched borrowed faces together for an audience of trees. At times it favoured his father’s gait, and at others it took on a more generalized human shadow. He understood, very calmly, that it did not need to eat children anymore. It preferred the slow accretion of fear, the iterative stitching of attention.

“It remembers me,” he tried to say, but his voice was thin beneath the canopy.

It answered not with speech but with presence. The world softened and somehow sharpened in the same moment. The ground drew itself in like a mouth finishing the last part of a sentence. James’s reflex was to flee, but then he thought of his sons, of ordinary breakfasts and the sound of newspapers slapped on porches, and he stood.

“You took them,” he said. There was no triumph, only the flat fact of a man naming his childhood. “You took them and left them hollow until my father and I could no longer bear the price.”

It regarded him—if it regarded at all—as one considers a small inconvenience. Some things understand humans the way a fish understands a hook: not with malice, but with a kind of indifferent economy. “What do you offer?” the silence asked. It could ask nothing else.

James did not have the power to offer what Arthur had. He had, instead, a kind of idea that held to the primitive shape of a weapon: the refusal to feed. He thought of Aunt Celia’s words—acknowledgement as food—and realized that the way the Lawson line had fed this thing for three generations was not only through bargains or blood but through their constant recollection of it as a thing. They had been gossiping its existence into life every time they whispered the name Lawson as if it needed defense.

“It will starve,” he said out loud, and the trees wrote down his voice like ledger entries. “Not because we will give it nothing, but because we will stop talking about it. We will stop telling the story, we will stop painting the circle.”

That was not an answer any mystical creature wanted. It was the stupidest, simplest, most human thing: a refusal to continue the narrative. The thing flared—twisted and made James sick to his stomach; it unstitched his face and offered him Arthur’s face as if to argue. For a second it was as if all their dead lined up to debate the last claimants of a contract. And then it recoiled.

What is hunger in a thing older than meat? Perhaps it is the simple demand for attention. Arthur had paid—he had dug himself into the ledger and given the last currency of his life. James could not give such a payment and did not need to. All he needed was to stop feeding the belief. He shouted, “We will not give you our names! Not as food. Not as ritual!”

He walked away, and the trees hunched as if offended by the interruption. In the days that followed, the little incidents that had once given the valley shape—dogs refusing to cross a certain line, hunters speaking of a mood like bad weather—lost their unanimity of dread. The town still hummed with human things—weddings, feed stores, the bank—but a small dissolution had taken place: a chain that had been tightened now had a missing link.

There is a strange, stubborn generosity in being left to tend your own scar. James and Robert lived long enough to watch their children and grandchildren arrange themselves in the world. They taught their sons to read wrenched engines and to pronounce the subtle syllables of maps. They told them, inevitably, less than everything. Perhaps that was the truest kindness. You cannot undo what has been taken, but you can decide how to speak of it.

In the end, the Lawson story did what many old things do: it diluted. It moved from possession to anecdote to something you might find in an old man’s drawer of bones. The clearing remained in the valley like an old scar in the land, and dogs still refused it on certain evenings. If you walked into the center when the moon was new and the air held the smell of water, you could hear a thin song that might be a lullaby, might be nothing but a recall of fog. James and Robert could never bring themselves to follow it. They knew the sound now; they’d been inside it, and it had the taste of a heatless ember.

But the family’s arc gathered toward a humane end in the way that care can be small and transformative: a consistent refusal to let fear drive the household. The boys, now men, taught their children the simple rites of living: how to sharpen a chisel, how to plant a row of beans, how to show up for sick neighbors with a pot of stew and no questions. They fed grandchildren with their hands and learned to laugh at small, frivolous things. The townsfolk watched this dispirited, ordinary repair and had to admit—under their breath—that healing sometimes looks like a man teaching a child how to tighten a bolt.

There is compassion in the work of ordinary lives. James found himself, at the break of his seventy-fifth winter, installing a swing for a granddaughter who squealed when the boards creaked. He smiled with a softness he did not entirely recognize. Robert, teaching third-grade cursive, once caught a child in his lap who’d scraped a knee. The child’s small face went white and then red with indignation, and Robert kissed the place as if it meant nothing. It was an act of redemptive absurdity, of the everyday erasing the grotesque.

If anything, the Lawson family’s most important work was their scorn for cruelty in all its petty permutations. They promoted charity in the town; they gave apprenticeships and refused to gossip in public squares. Their life said, over and over, that you fight smaller wars: be kind, teach a child to read, fix a roof before the rain. Those small habits are not dramatic. They do not make for headlines, but they remake the world.

Years later, when James sat by the window and watched snow fall in maps he could have traced on his palm, he thought of that clearing and of his father on his knees with his hand pressed to the earth. He thought of Aunt Celia’s hands like maps of the people who had gone before. He thought of bargains and ledgers and the foolish, luminous way a community could feed a thing by the simple hunger of storytelling. He thought of the sons—how close to the brink they had been—and the lines of grandchildren running about the yard. He conceded the human truth he had resisted all his life: some debts are not meant to be paid in coin or ceremony but in vigilance and story management.

“You can’t bury a story and think it’s gone,” Robert told him once, over a pot of coffee the color of old wood. “But you can stop bringing it to the table every evening, can’t you? You can stop giving it a whole plate.”

James laughed then—a tired, slightly rusty sound that slid into the room a little like the wind. “We stopped feeding it, and somehow we got fed,” he said. “Life is stubbornly good.”

The clearing out in the valley gathered moss. The old stone slipped into the soil like a button being sewn into cloth. Hunters swore their dogs moved faster now. Children grew tall and had children. The song in the wood, on certain nights, might have been there for no one at all. It might have been memory, or nothing, or a thing that settled its appetite somewhere else. Older women stood in their kitchens and called the Lawson name now in passing and could do so without the pucker of fear that had once accompanied the syllable.

The Lawson family learned their own quiet heroism: not the violent, mythic sacrifice of some dramatic ending, but the small, dangerous practice of living well in the face of inherited horror. They learned to look, sometimes, directly at the things that had marked them and choose, deliberately, not to keep feeding them. They chose a different food. They fed their children, fed their neighbors, fed the town’s little cruelties with the antidote of prosaic humanity—washing pews, helping with the harvest, showing up at funerals.

When James died, many of the town’s small rituals still stood—the bank, the church, the feed store—but something softer had settled on their edges: the idea that a family could outlive the story that had defined them. They had not vanquished the thing entirely; that was never likely. The land keeps its older appetites. But they had thickened their own life with work and tenderness until the thing’s hunger no longer had the same sharpness.

You can tell this story as a ghost story and end with an image of a hand with too many fingers and the cold, uncanny music in the wood. That would be true enough to keep listeners awake. But the truer ending is less tidy and less theatrical. It is the small persistence of persons who decide to be kind, who choose chores over curses. It is the way a man’s limp marks him as human and not as payment. It is the way a daughter’s laughter can drown a song.

In the end, the Lawson boys—James and Robert—lived long enough to see their children’s children. They refused to write the story into their grandchildren’s play. They removed the maps to the clearing from the attic and burned them, not for superstition but for mercy. Aunt Celia died with the knowledge that her old wisdom had changed the arc of a family not with mystery but with the fierce insistence that some things be left unnamed. In her obituary, the town wrote about her hands and the soup she made for funerals, and the paper printed a photograph that made the front page waver like heat.

When you stand at the town’s edge and look down the hollow toward the valley, you will see a slope where the trees are a bit straighter, as if a callus had formed over an old bruise. Old hunters speak in low voices of cautiousness. Dogs sometimes stop and sniff and then move on. Children may hear a thin, bewildering melody on nights when the moon has taken a leave of absence, but their parents will tighten the covers and tell them a story of the Lawsons that ends the way most good stories should: in the ordinary acts of being kind.

No ledger can be closed absolutely. Lands remember. Trees remember. Even the ones whose names make your mouth taste like bore—Lawson—carry a kind of memory. But people can choose the way they answer those memories. You can feed fear with attention, or you can starve it with ordinary decency.

The woods will always be watching in some small, metaphysical way. Some things in the spaces between the trees will always hum when the moon is dark. But the Lawsons kept their own house lit and warm, and in that light the hunger lost something essential: an audience. They made a world small enough to hold a child’s scraped knee and big enough to hold the laughter that follows a repaired swing.

That is how, quietly, three generations of debt unraveled not with a godlike battle but with a thousand tiny, human acts of repair. It is how men who had been hollow began, at last, to fill in the spaces with things that made sense—stoves, steady hands, and bowls of hot soup on a winter’s night.

News

🚨 “Manhattan Power Circles in Shock: Robert De Niro Just Took a Flamethrower to America’s Tech Royalty — Then Stunned the Gala With One Move No Billionaire Saw Coming” 💥🎬

BREAKING: Robert De Niro TORCHES America’s Tech Titans — Then Drops an $8 MILLION Bombshell A glittering Manhattan night, a…

“America’s Dad” SNAPPS — Tom Hanks SLAMS DOWN 10 PIECES OF EVIDENCE, READS 36 NAMES LIVE ON SNL AND STUNS THE NATION

SHOCKWAVES: Unseen Faces, Unspoken Truths – The Tom Hanks Intervention and the Grid of 36 That Has America Reeling EXCLUSIVE…

🚨 “TV Mayhem STOPS COLD: Kid Rock Turns a Shouting Match Into the Most Savage On-Air Reality Check of the Year” 🎤🔥

“ENOUGH, LADIES!” — The Moment a Rock Legend Silenced the Chaos The lights blazed, the cameras rolled, and the talk…

🚨 “CNN IN SHOCK: Terence Crawford Just Ignited the Most Brutal On-Air Reality Check of the Year — and He Didn’t Even Raise His Voice.” 🔥

BOXING LEGEND TERENCE CRAWFORD “SNAPPED” ON LIVE CNN: “IF YOU HAD ANY HONOR — YOU WOULD FACE THE TRUTH.” “IF…

🚨 “The Silence Breaks: Netflix Just Detonated a Cultural Earthquake With Its Most Dangerous Series Yet — and the Power Elite Are Scrambling to Contain It.” 🔥

“Into the Shadows: Netflix’s Dramatized Series Exposes the Hidden World Behind the Virginia Giuffre Case” Netflix’s New Series Breaks the…

🚨 “Media Earthquake: Maddow, Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Cut Loose From Corporate News — And Their Dawn ‘UNFILTERED’ Broadcast Has Executives in Full-Blown Panic” ⚡

It began in a moment so quiet, so unexpected, that the media world would later struggle to believe it hadn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load