Part II — Camp Deming: A Strange Freedom

Camp Deming, New Mexico was a world unlike anything Georg had expected.

There were fences and guards, yes—but also soccer fields, classes, newspapers, and food better than what he’d eaten during the war.

“Americans treat prisoners better than Germany treats its soldiers,” one POW joked as they ate canned peaches on a summer evening.

Many prisoners relaxed, resigned to wait out the war in relative comfort.

Not Georg.

He studied guard rotations.

He collected scraps of civilian clothing.

He practiced English obsessively.

One night a fellow POW, Dieter, asked, “Why do you study so much? You think you’ll need English in Germany?”

“No,” Georg answered. “Because I may need to speak it for a very long time.”

Dieter laughed. Georg didn’t.

By summer 1945, the war was ending. Repatriation loomed. Home meant ruins. Hunger. Occupation.

“I will not go back,” Georg whispered to himself. “I will not return to a country that abandoned me long before I abandoned it.”

And so the plan was born.

Part III — The Escape (September 10th, 1945)

2:17 a.m.

The desert was cold enough to bite skin. Searchlights moved in slow, predictable arcs.

Georg slipped through a window he had loosened for weeks. He crossed the compound, reached the fence, and crawled through the gap he’d cut strand by strand using a sharpened spoon handle.

Beyond the fence was silence.

And then—freedom.

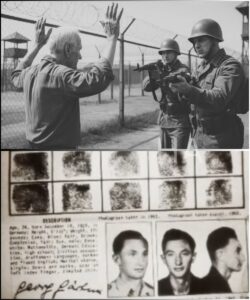

Bloodhounds hunted him at dawn. Cars scoured the highways. Radios warned civilians:

“Escaped German prisoner. Approach with caution.”

Georg walked north.

Not south into Mexico where he might vanish.

North—into the very country he was supposed to be fleeing.

Into the country he secretly hoped to call home.

Part IV — Becoming Dennis Wilds

Somewhere in the Colorado mountains, Georg Gärtner died.

In his place was born Dennis F. Whiles, a drifter from the American South with a vague past and a strong work ethic. Forged papers. $40 in savings. A battered English phrasebook.

His first job: washing dishes in a Denver diner.

The owner, Mrs. Callahan, eyed him warily.

“You talk funny. Where you from?”

“The South,” Dennis said.

She squinted. “Far South?”

He nodded.

“Yes, ma’am. Very far.”

She shrugged. “As long as you work hard, I don’t care if you’re from the moon.”

Over time, Dennis absorbed America through every sense—radio dramas, newspaper comics, bar conversations. He practiced speaking until his accent softened into something unplaceable.

He studied American mannerisms. Learned how to shake hands the right way. How to complain about taxes. How to talk about baseball with reverence.

And slowly, impossibly, he began to feel American.

Part V — Love

Her name was Mary.

A waitress with auburn hair and a laugh that made Dennis forget he was a man with a secret. They dated quietly for three years. He became a father figure to her young daughter, Elise.

One evening, after Elise’s birthday party, Mary brushed frosting from Dennis’s cheek and said softly:

“You’re good to us. Don’t you ever want… more? Marriage? A family?”

Dennis froze.

Marriage meant paperwork.

Paperwork meant background checks.

Background checks meant handcuffs.

“I can’t,” he said.

Mary’s voice broke. “Is it me? Am I not enough?”

“No,” Dennis whispered. “You are the one thing I wish I could keep.”

The breakup devastated him. But it kept them safe.

Years later, Dennis still dreamed of her.

Part VI — A Life in Shadows (1954–1983)

For nearly thirty years, Dennis lived a life built from fragments:

A ski instructor in Colorado, charming tourists with stories that almost—but not quite—resembled his own past.

A television repairman in California, his precise hands perfectly suited for delicate circuits.

A gardener in Nevada, tending roses that bloomed better under his care than they ever did with their wealthy owners.

He attended barbecues. Helped neighbors move furniture. Paid taxes. Saved receipts. Renewed driver’s licenses under quietly forged identities.

He formed friendships. Lost some. Kept others.

A normal American life—except for the guilt and fear that sat like a stone in his chest.

Every Fourth of July, fireworks cracked overhead like artillery, and he wondered:

To which country was he betraying loyalty?

Germany, which had used him?

Or America, which he loved under a false name?

The paradox tore at him.

Part VII — The Ghost Returns (1983)

In 1983, Dennis read a magazine article titled:

“Whatever Happened to the POW Who Escaped Camp Deming?”

He almost dropped the magazine.

There it was.

His real name.

His wartime photograph.

A line that froze his blood:

“He remains at large.”

The past had not forgotten him.

For weeks Dennis barely slept. A single knock at the door made him choke on fear. A police siren in the distance sent him trembling into the bathroom.

It became clear:

He could not die as a lie.

He wanted—needed—to be Georg again.

Part VIII — The Surrender

September 11th, 1985.

The walk to the immigration office felt heavier than any of the twenty years he had spent hiding. When he stepped inside, he felt his knees weaken.

“Name?” the clerk asked.

“My name,” he said softly, “is Georg Gärtner.”

She blinked. “I’m sorry?”

“I escaped a POW camp in 1945. I have lived here since. I have come to surrender.”

Silence.

Then she whispered, “Oh my God.”

Within hours, journalists stormed the building. Cameras flashed. Microphones thrust forward. Headlines erupted across the country:

“THE LAST NAZI POW FOUND IN CALIFORNIA.”

“HIDING IN AMERICA FOR 40 YEARS.”

“HE CHOSE THE U.S. OVER HIS HOMELAND.”

But what shocked Georg most was the tone.

Sympathy.

Curiosity.

Respect.

Not anger.

One veteran wrote:

“You were our enemy once, but you became our neighbor. That counts for more.”

Another wrote:

“It takes courage to escape. But perhaps greater courage to surrender.”

Prosecutors reviewed his case. Technically, he had committed crimes. But none in his forty years of free life.

A judge said gently, “Sir, if every citizen behaved as well as you have, we would have little need for prisons.”

The country—astonishingly—embraced him.

Part IX — A New Freedom

In early 1986, the government made a decision without precedent:

Georg Gärtner could stay. Legally.

The man who had fled America to remain free was now welcomed by America to remain free.

He received a green card. A path to citizenship. Thousands of letters of support. Invitations to interviews which he mostly declined.

He said during one rare television appearance:

“I did not choose America because it was powerful. I chose it because it was kind.”

For the first time since he was a teenager, he lived under his real name.

No lies.

No forged papers.

No midnight panic.

Just Georg.

Part X — The Final Years

Georg settled into a quiet life in California, working part-time as a maintenance man. He could have sold his story for wealth. Hollywood wanted a movie. Publishers begged for a memoir.

But he said, smiling softly,

“I have had enough adventures for ten lifetimes. Now I want peace.”

He never returned to Germany.

America had become his country not by birth, but by choice. A choice he reaffirmed every day for sixty-eight years.

On January 30th, 2013, Georg died peacefully in a veterans hospital at age 90—wrapped in a blanket printed with the American flag.

One nurse, unaware of his past, said,

“He must have served during the war.”

In a way, he had.

He had served America with the quiet dignity of a man who chose goodness when the world offered him violence.

Epilogue — What It Means to Belong

Georg Gärtner’s story defies categories.

He was a soldier fighting for a regime he despised.

A prisoner who found humanity in the enemy.

A fugitive who became a model citizen.

A man who escaped a prison camp only to build a prison of lies around himself.

And then, at last, a man who walked back into captivity to set himself free.

What he taught us is simple:

Identity is not where you are born, but where you choose to stand.

Loyalty is not blood, but the life you build.

And sometimes the bravest thing a person can do is tell the truth—even if it takes forty years.

In the end, Georg did not come to America as a conqueror or a refugee.

He came as a human being searching for a place to belong.

And he found it.

At last.

News

“My Mommy Is Sick, But She Still Works…”—The Little Girl Whispered, And The CEO Couldn’t Stay Silent

He crossed the lobby. “Hey there,” he said softly, crouching to her level. “You waiting for someone?” The girl turned….

“Sir, My Baby Sister Is Freezing…” Little Boy Said—The CEO Wrapped Them in His Coat & Took Home…

Daniel turned back to the boy. “What’s your name?” The boy swallowed. “Malik.” “How long have you been here, Malik?”…

“Mom said Santa forgot us again…”—The Boy Told the Lonely Billionaire at the Bus Stop on Christmas…

The boy, around six, had a red nose and wide eyes that missed nothing. His jeans were a little short,…

The Billionaire Lost Everything, Until His Cleaning Lady Changed His Life In Seconds

Nathan’s fingers hovered over his keyboard. He typed like a man hammering nails into a sinking boat. He tried to…

“Look At Me Again And You’re Fired!” The Ceo Yelled At The Single Father.Which She Later Discovered.

The room froze in unison. A collective stillness, like a photograph taken by a flash of lightning. Somewhere, someone’s phone…

Single Dad Heard Little Girl Say “Mom’s Tattoo Matches Yours” – Shocking Truth Revealed”

Evan felt his body react before his mind did, like his heart had a reflex and it didn’t care about…

End of content

No more pages to load