The room, which had been running on the low hum of commerce, stopped the way a machine stops when its oil is suddenly removed. Eight thousand. For some of the men gathered it was the equivalent of planting a whole year’s crop, or buying a mill’s inventory. The governor of sums paused in his head and tried to map the price to what he thought he should be buying—field hands, a seamstress, a house cook who could turn sorrow into biscuits. The prices did not fit. They should not have fit.

Whitman read on. The seller’s affidavit insisted on discretion, on the necessity of secrecy, on the presence of more than a few witnesses. It insisted on one thing men in power rarely had to consider: the woman possessed, in practice, a memory like a ledger. It said she could recite with exactitude any document she had seen; she could reconstruct contracts, replicate a ledger’s columns, remember the precise turn of a phrase in a letter read under a household lamp. The affidavit suggested—or threatened—that what she contained, if stirred up and read aloud, might bankrupt men in an hour.

A ripple of fear and avarice passed through the crowd like a current. They understood, because they had all built their lives on the impermanence of other people’s silence. If a man could perfect his forgetting, if debts and errors could be smoothed away with paper and precedent, then this woman’s memory was a storm on their horizon. Their reasons for wanting her could be bought under the same roof by different pretenses: to consult, to exploit, to lock away. A few men sniffed at the air as if they could smell destinies burning.

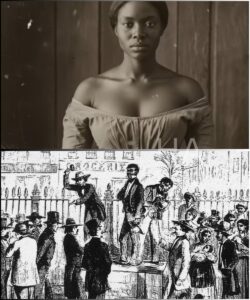

Bidding began with the measured cession of numbers and ascended into a catharsis. A cotton broker bid nine thousand, and a banker answered at ten; three rivals edged the stakes to fifteen and then to twenty thousand. Men who had come to purchase labor found themselves purchasing leverage. Men who had come to rub elbows left with their fingers stained by the possibility of exposure.

She stood upon the block and did not sway. Her face, observers would later say, was wry; it was an expression that looked like someone reading the end of a story they’d already written. Some would call it a smile, others would call it the slackness of someone transfixed. She said nothing. She looked, when asked, beyond the exchange’s columns to a small window at the back of the room, as if seeing something in the knobby glass that no one else had the patience to find.

The man who won her that day did not look like a man who had won anything. At first glance he was the sort who could be mistaken for a privateer or a land agent—neither of which he was. He called himself Rowan Hayes, and his accent had the precise fray of a man who had spent time in ports and bank vaults but had been taught to listen more than to speak. He paid in bank drafts drawn on a name that belonged to a timber concern up the river, though the timber concern itself seemed a body without address. Rowan took the woman’s hand with a care that was not tenderness so much as reverence for an instrument.

They left the exchange and no one in Montgomery could later agree on the route of Rowan’s carriage. There are always such disagreements in cities that like to pretend to govern the past. Some said they had fled north, others said they had taken the back roads toward a timber yard where the draft had been issued. Men returned to their ledgers and their wine and tried to feel the solid contours of their lives. Some could not. In the following eighteen months two of the men who had risked fortunes on the auction were found dead under strange circumstances; another walked into a river one winter night and was never quite found. People began to suspect, with the quickness of those who are like to be guilty, that their newly acquired terror was being paid back in blood.

This was not an accident. Lila did not fall into the role of strange historical artifact by happenstance. She had cultivated this impossible ledger inside herself like a room filled with cross-stacked papers, and she had planned its revelation as deliberately as a woman organizes a cabinet of receipts. There had been a teacher, her mother’s friend, a Quakerwoman from the North who taught in whispers and in stolen nights. She had been taken away for her trouble—arrested for violating the state’s law that forbade the schooling of enslaved people—and the woman had died with a note pressed into Lila’s hand. The note had not been rich with advice, but it had carried a mandate. “Remember,” it said, “and count.”

That phrase—Remember, and count—had been the quiet engine of Lila’s life. She learned to read in the shadowed hours, fingers tracing letters like seams. She taught herself shorthand, the small tricks of notation, the patterns that make numbers speak. She worked in houses whose owners thought their confidences were the kind of private currency that no one in servitude could ever decode. They were wrong. She sat at the edges of parlor politics and the center of household finance and lined up the ledgers in her mind like a fleet of ships.

Lila’s memory did not arrive whole. It was sharpened by practice. She learned to anchor words to objects: the phrase in a mortgage tied to the oil stain on a desk; the cipher of a claim folded into the grain of a banister. She learned, too, something that few of the men around her suspected: people live lives of recurring patterns, and when you learn to look for pattern you learn to predict men by their repetitions. Men reveal themselves by the way they light a pipe before they confess a debt or by how a finger taps when falsehood is about to come. She remembered not because she was empty and fed on memory, but because she had trained herself to make the memory work like a map you can live from.

When she was sold from household to household, she made choices—calculated acquiescences and small resistances—that let her see more. A good servant is unremarkable; a remarkable servant is invisible. She made herself the background to conversation and the mirror to people’s worst habits. Men who never thought to put a letter in a drawer that could be seen by a servant were saved by arrogance. They assumed their honesty of deed would protect them. Lila stored their realities like pennies.

She also learned what information could do. Secrets are not only weapons; they are also currency. They can be traded for shelter or for silence, for passage or for protection. Her earliest acts of leverage were pragmatic: a ledger reproduced to win extra days at a port, a letter read aloud to correct a misallocated order that would have left twenty families poorer, a note of sympathy given in place of a needed favor to a pregnant woman who had no other comfort. She learned that when your mind holds other people’s accounts, you can walk hedge-lined lies and extract small mercies.

There came a moment when extracting small mercies felt like stealing crumbs from a table that would never be paid back. She watched men take and take without ledger or apology. She watched owners argue about the paper-based bones of other men’s lives, and she felt in her chest a ledger that grew heavy with unpaid sums. She began, quietly, to expand the terms of repayment. She wrote small anonymous notes, the sort that cause a man to clear a shroud from a ledger and stagger. She sent a letter to a widow revealing her late husband’s debts, causing a quiet settlement that put food into a child’s mouth. She hinted at a corrupt factor’s miscount to a rival and saw a debt exposed; private shame became public reimbursement. When she could, she demanded money not as majesty but as necessity, and the little tokens of safety began to collect like the margin notes of a long audit.

These were small reversals, nothing compared to what she planned next. She had two goals: independence and to create a mechanism by which memory itself could be translated into a life that was more than the sum of bargains. She could have sold herself quietly, gone north with a buyer who would have kept her books and her person, lived on the thin, borrowed safety of someone else’s discretion. But she wanted to change the terms not only for herself but for the system that treated people like furniture. So she arranged the auction.

It took cunning and contacts. She found a lawyer—Samuel Crozier, who had been shoved to the margins of the profession by men who preferred comfortable complicity to legal scrapes. Crozier liked the idea of a spectacle that would reveal the hypocrisy of a town built upon confidentiality. He also liked money; what lawyer does not? He proposed making the sale public, making the ledger of Lila manifest by placing the knowledge in the open market. Lila, who had the habit of measuring men’s readiness like a seamstress measuring cloth, agreed because she knew an open market would turn fear into currency. “If you sell men the fear,” she told Crozier once in the lee of a rickety inn, “they will act as if the fear were worse than the goods.”

Crozier did his work in whispers and in sealed envelopes. He found a mannerly auctioneer and a notary who would sign and then sleep. He wrote a sealed affidavit that suggested that the woman could recall any document she had seen. He planted the rumor that the seller was a gentleman who had kept the woman as a curiosity, using her memory to hedge bets. The rumor spread to the men who traded in fortunes and secrets, and on October morning they came holding their wallets open like prayers.

What she intended to happen, in the clean lines of her plan, was this: let them buy what they feared; let them pay; watch the city reconfigure itself under the pressure of its own paranoia. She did not anticipate, at first, the speed with which panic would translate to ruin. Men who had thought to bargain their way into the future became strangers to themselves. A banker called Thomas Reed ran from his house one dawn with his hair uncombed and never returned; his account books disappeared from the vault and his ledger entries failed to reconcile. A planter named Hargrove fell ill with a fever of anxiety that killed his sleep before it touched his body; he took to staring at the joints of his house like a man who suspects traitors within their own walls. In less than a year three men lay in unmarked graves edged by the hush that follows scandal.

Crozier, who fancied himself clever, had expected the town’s men to squabble and then settle. He had not expected to see men bent by fear into ruin. He had not expected that among the buyers might be a man like Rowan Hayes, who, unlike most, had spent the last decade learning to collect not only receipts but leverage. Rowan was a broker of secrets, a professional who had set up a modest business making sure certain truths were managed for certain pockets of power. He bought Lila because he thought he could control the market; he believed that owning the ledger would let him sell silence to anyone both north and south.

Rowan made one mistake: he did not regard the mind he bought as a passive archive. He had counted on a woman who would be compelled by need to sell her memory back to him, to become a servant in service of profit. He thought he could make her work for him as a well-versed clerk, pointing to miscounts and pointing to misdeeds if and when it served him. He did not see that the ledger inside Lila contained not only accounts but a slow-burning reckoning. She had placed into herself the names of the men who had hurt her, and she had also placed into herself a ledger of small debts owed by them all.

There was a first turning. Lila sat in the small house Rowan had taken in a township by the river and found the quiet room given to her where she could read the papers and breathe. Rowan grew confident that he could take her to New Orleans or even to Charleston and make a living on selling what she knew. He offered her money; he offered her promises of passage. Lila accepted none of his offers. Instead she began to speak, not by spilling names for sale but by composing letters.

She wrote letters to those she had observed, letters polite and precise, informing them that she remembered specifics they had discarded in the assumption that memory could be replaced by paper. She outlined variegated debts: promises unfulfilled, land transactions that had been improperly recorded, and simple facts that, when made public, would complicate the proudest lineage. Some men paid. In private rooms they arranged discreet settlements; money passed hands in the dead hours. Others refused, certain that the law would stand between their secrets and the woman with the uncanny mind. Those men found themselves visited by accidents, by audits that made their holdings look porous, and by reputations that frayed.

The thing Lila learned quickly was that justice could be rendered in many currencies. For some, the right letter meant a small safety. For others, a public account could be the difference between a firm estate and the slow evaporation of dignity. She used what she had—memory—as both shield and scalpel. She did not attempt wholesale revenge. She was not driven by the alchemy of malice. She wanted leverage mostly because leverage bought an island of choice.

When the war came and the silhouette of conflict creased the country’s horizon, Lila’s ledger changed significance. Men in uniforms and those who learned to trade in uniforms looked at her not only as a resource but as a strategic node. A Union officer, sharp-eyed and not given to sentiment, learned of her through contacts in intelligence. He was not surprised that a person with her capabilities would be of interest. He was surprised that she had not already been smuggled away by a buyer who would have sold her memory to the highest bidder. Rowan took no such measure; he was not a man who liked to plan beyond his immediate margin.

They brought Lila to a tent where maps were spread and the country’s seams looked thin to the touch. The officers asked for names and routes. She remembered shipping receipts, the times of departures, the cards of men who moved cotton through crooked channels. She recited routes that led to foreign ports and the names of agents who had been paid to keep the Confederacy’s lines open. The Union found in her memory a set of coordinates; they organized a few night operations and learned quickly that the place where a ledger’s accuracy meets a navy’s reach can realign a campaign in ways men like to say are “decisive.”

She worked with them, not because she loved the Union or because she hated the men who had once set their boots in her house; she worked because the new currency—the price of liberty—suddenly included not only a moral accounting but a practical necessity. If her memory could shorten a war and, in the process, weaken the structure that had made her bondage possible, then memory had served a use beyond personal accounting. She watched, with the same dry composure she had watched men’s ledgers, as convoys were intercepted and deals that had financed armies faltered. She felt no visible joy at the ruin it imposed upon men who had held her down. She felt, instead, a strange, keen relief, like a woman correcting an imbalance that had been set too long.

The war ended in ways that old men still argue over like card players arguing the proper rules of a cut deck. For Lila, the ending was a softer thing: a moment when documents became purchases that could be made by someone like herself. She had been paid by the Union in more than the coin of an agent’s approval; she was given certificates of freedom and a small sum that could be used in an era of new, uncertain liberties. Rowan, who had thought to profit from her, lost his control. The man who once had the audacity to hide in doors to collect payments found himself on the wrong side of new authorities and the wrong side of men who had been shut down by evidence. He left the city one morning with a bag of coins and a look that a man takes on when he leaves a job he has no more desire to claim.

Lila used the money with a patience that suited her memory. She purchased a narrow house in a town that was less loud with ruin and more forgiving of reinvention. She enrolled in night classes—there were those now—and she taught herself to write with elegance, not because she needed to make men confess but because she wanted the world’s language to be hers. She wrote letters to old acquaintances—some honest, some bitter—and she accepted payments when people strutted to her door with their hands out. But the thing that most held her attention was children.

She began, with accounts careful as any ledger, to fund a small school for freed children. It started as a single room on a narrow street where girls and boys, many of whom had been kept from letters like birds kept from their wings, sat wide-eyed and attentive. Lila taught them not only to read but to see the patterns of the world—to translate numbers into narratives, to understand that a contract is not a sacred instrument when it has been used as a weapon. The school grew because she believed that memory is not only the thing that keeps the past alive but the tool by which you can wield the future.

There were complications. Men who felt stripped by exposure found ways to strike back in the slow, ordinary cruelties of gossip and social shunning. Some attempted to sue her for extortion; a few tried less lawful things—smear campaigns and threats that required nightly vigilance. But she had allies now, scattered across cities, who owed her not only gratitude but the sense that the world could be re-angled. The children in the school were her ledger of the future. She set the rules of the place like one balances a book: fairness, precision, and the firm insistence that truth merits a living.

Years passed and Lila’s ledger of small accounts became large and deliberate. She acquired property, not as trophies but as safe houses and rooms where old women could sleep with a measure of safety. She wrote letters—some punitive, some merciful—and saved records in a bank of sorts: the human bank where trust is kept not in vaults but in memory. People paid for silence, some because they were frightened, others because they appreciated that Lila’s work preserved families from shames they would rather contain. She never broke men beyond their dignity; her aim was not to revenge but to set balances straight. Where harm had been done, she made restitution possible; where fraud had been committed, she made renunciations public and negotiated settlements that put money back to where it mattered.

At times she was asked if the work was revenge. She sometimes laughed, a small sound like coins settling. “Accounting,” she said once to a young woman who had asked the question with the frankness of someone who believes history a ledger to which she has a claim, “is not revenge. It is the recognition that the books must reconcile.”

There was a final gesture she made that would, in stories afterwards, be called both merciful and cunning. In the smoke-dark spring of a decade later, a letter arrived at the school from a planter’s widow. The woman wrote in a hand that shook but bore the marks of an education she had once known. She had read of the school and of the woman who had been sold on an auction block. She did not ask for forgiveness. She asked instead for the education of her grandchildren, five boys whose futures she wanted insulated from the errors of the past.

Lila read the letter with a stillness that was careful. She could have demanded payment; she could have insisted upon public acknowledgments of sin. Instead she sent the boys to school, and she taught them not only to read but to feel the world’s numbers with an ethical sense. She made them wash the floors of the classroom until their hands learned honest muscle. She made them apologize for things they had not yet done but might have been taught to do by some inherited arrogance. In the end, the widow became a frequent visitor, bringing bread or mending the school’s curtains.

The street that watched the school change over time liked to tell a tale: that one day the widow left a folded note and a small parcel at Lila’s doorstep and that the parcel contained a ledger—a family account book that had been closed for decades—and that inside it were the names of men who had owed the family debts of conscience. Lila read the book, turned its pages, and folded the paper into her chest like a citizen measuring the terms of an oath. She made a list. She made a plan. But she also taught the boys the ledger’s final lesson: every account—political, economic, moral—must be reconciled not by humiliation but by repair.

In the end, the most humane thing she did was simple. Lila used her life’s accumulation of secrets and money to set up a foundation that funded education, access to law, and medical care for the families she had once been asked to serve as a silent witness. She married no man of consequence; she refused the proposals of men who thought to turn her into a trophy of reform. She married, for a brief season, the work of the school and the sanctuary she had built. She died in a house that smelled like chalk dust and lemonade, with the sound of children playing in the yard and the sound of a river like a foreign tide beyond town.

Her funeral drew a crowd that was uneven in its composition: former owners who arrived with hands unsteady and eyes lowering like men stepping into a room with wrongfully folded napkins; former teachers who had watched her unspool the ledger into law; former children turned adults who wept openly and wore her name on their tongues like a benediction. They carried her to the graveside and there, a man who had once bid for her on the exchange stood and read a passage he had written—nervous, precise—about debts and reconciliation. He spoke of how a single woman’s memory had unsettled a city and how a single woman’s teaching had steadied a generation.

There are stories that demand two endings: one in which justice is swift and noisy and another in which justice looks like the gentle rounding of accounts as year follows year. Lila’s story sits in the second. In the top-shelf versions of history she is sometimes cast as a weapon; in the bottom-shelf versions she is made a footnote in the desperate greed of men who traded in humans. But those who had the small, inconvenient privilege of being present know something else: that she was always more than the ledger she carried, that the secret she commanded was not the names she could recite but the choice she made to turn memory into a tool for the living.

The thing she had refused to confess in life she confessed for the record in a short, plain letter she left to be found after her death. “They thought owning my body meant owning my knowledge,” she wrote. “Memory is not owned. It is lent to the future. I returned it better than I received it.” She placed the letter in the school’s archives and then sealed it with a small, flourished loop.

History keeps many voices under its floorboards. Sometimes, when the wind is right and the city grows quiet, the echoes of those voices make themselves known: a note of a song, the pattern of a melody, the way a face remembers the curve of a thing. Lila’s ledger lives on not because of the price she once fetched—men who remember that auction still argue whether twenty thousand dollars covered the true value of a woman who could recite an estate’s deeds—but because she reframed what value meant. She turned the instrument that had been used to remove her into a way of returning agency to those removed by the ledger’s sums.

People ask, decades after the fact, whether she was justified in leveraging the secrets she had collected. They argue about the ethics of the payments and the damage caused to men who had once lived by omission. My answer is not a tidy one because it is a human answer. She had been given no recourse when the men around her treated the world like a ledger and servants like enumeration. She had been taught to read and then sold into the hands of those who used that literacy as if it were a tool to be sharpened on their own behalf. When the chance came to turn toward a restitution of a different kind, she took it.

That, in the record of the city, is the impossible secret: that a woman sold for an impossible sum did not spend the profit on revenge alone but on building rooms where a child could learn to write her own name as if it were a passport out of the past. She taught the city a stubborn, cumulative thing: that memory, once set free, works not merely as accusation but as architecture. It constructs bridges over ravines that were once only trenches dug by men who preferred profit over people.

When the auction records were finally examined by historians who were less interested in the scandal than in the undercurrent of ordinary courage beneath it, they found erased ledgers and sealed pages and an envelope marked with a name that was never quite the same as the woman who stood upon the block. But they also found notes—marginalia in spines of books, a list of children’s names framed and preserved—and a thick, leather-bound ledger in the school’s safe where a woman had kept receipts and letters and small parcels of paper that proved not the size of her payment but the scale of her mercy.

There are ways to be remembered that are impossible to confine to a marble monument. They are quiet, inconvenient, and finite. Lila’s most durable monument is a schoolhouse with a stable roof, a garden full of children’s laughter, and an archive of letters that record the small reconciliations that make a neighborhood salvageable. Men who once trembled at the mention of her name sometimes walked by and, in their old age, left coins in the collection box with a hand that did not steady. The boys she taught told children their children: you can count on your memory not because it makes you feared but because it makes you responsible.

When the last page of her life is turned, we are left with a simple arithmetic: power that lives by secrecy can be subverted by the patient practice of remembrance. Lila’s ledger is not an instrument of terror but a ledger of repair. The most expensive thing men ever bought in that city was not the woman, nor the secrets she held, but the knowledge that their power could be checked, that their ledgers could be balanced. In the years that followed, fewer men felt as invulnerable in rooms where they supposed themselves private. They learned that there are accounts that cannot be erased without a witness who will remember.

If you stand now where the exchange once stood—if there is still a place to stand—you will find, more likely than not, a shop or a café and the memory of a woman like a shadow moving across the window. Children run past and the river keeps its old, patient flow. Lila’s school vanished as schools do, transformed into bricks and then into other institutions, but the people who were taught there carried the ledger forward in the things they did: votes cast, signatures recorded, contracts drawn in public. It was a small, human kind of reform, the sort that does not make headlines but remakes a life.

Perhaps the most humane accounting of all is this: she used the only weapons the world ever gave her—memory, persistence, the ability to name a debt—and she paid it forward not by destroying a city but by rebuilding a corner of it. Legends like to call that impossible. But impossible is often merely the adjective men apply before they remember how to add.

News

End of content

No more pages to load