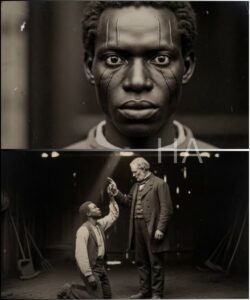

He understood less than the others; this was not his language. But he could feel the pattern of it in his chest the way one feels a distant storm: inexorable, insisting. Emmanuel spoke in a voice that moved like a river over stones—patient, exacting—and the words he used seemed to rearrange the light. When Nathaniel stepped into that circle, every face turned toward him. There was not lower or higher in the way their faces read him; there was recognition as if he had stumbled into a place where everyone already knew how to read him better than he read himself.

“You’re welcome to watch,” Emmanuel said in English. “But be warned: watching can change you.”

Nathaniel felt the truth of that sentence as though it were both a threat and a mercy. He stayed until the line between day and night dissolved into something else entirely: the orishas, the beings that Emmanuel invoked, were not explanations so much as presences. They moved like weather—anxiety, calm, thunder—and in that place the idea of master and slave seemed, for a moment, brittle.

Back in the house Nathaniel discovered an ache that was not purely physical. Dreams came afterward—rich, imperative, populated with figures that called to him by names that scraped his memory raw. He dreamed of forests that were older than maps, of rivers under stars he had never learned to name. He dreamed of an ax that split the air and of fire that spoke in clear declarative sentences about judgment and mercy. He woke convinced these were the kinds of dreams one either dismissed as fever or followed until they changed the horizon of one’s life.

Two weeks after Emmanuel’s arrival a field hand named Samuel died in the shade of a live oak. He had not worked himself to exhaustion. He had been resting. He had laughed at Emmanuel’s teachings days before and the men said afterward, between furtive flinches, that Samuel’s laughter had been different: sharp, affronted, like a lid slapped onto a container. Nathaniel accepted, reluctantly, rational explanations. Heatstroke, an undetected ailment, the country being what it was. His rational mind filed the event and then—because human beings will often prefer narrative to uncertainty—began to test an alternative idea desperately on its teeth: that there was cause to what the field hands whispered.

That alternative thought bled into another when a merchant who had come to weigh cotton prices fell dead on Nathaniel’s stoop with blood in his mouth, and then into another when a neighboring planter who had scorned Nathaniel for his obsession was found with his heart ruptured inside his own carriage. All of those events—freak, tragic, coincidental—collected around Emmanuel like a storm collects rain.

The overseer, Thomas Garrett, spoke bluntly. “This is not work that can be left unchecked,” he told Nathaniel, leaning his hard jaw against the study’s desk. “If the men won’t be managed, I’ll leave. I can’t run a plantation like that.” He left and did not return. Word moved through the county like smoke. Nathaniel had become strange. He had been seen in white robes. He had been seen kneeling. He had signed strange papers in a frenzy under a sky the locals said had blackened midmorning and burst into thunder the likes they had never heard. Men watched him as though he was an animal that had been liberated in a circus, and they hissed that he had become mad.

Nathaniel’s madness, if madness it was, had texture. He read, he learned, he asked Emmanuel questions that the man answered in parcels—never too much, never so much as to give away the thing that required commitment to keep. He learned the sixteen odu, their turns and webs, and he learned to use shells as divination, to throw them and read the pattern. He learned to listen. The learning did not make him gentler in the old ways. It made him other.

Margaret observed this with a coldness that was almost protective. Her instincts were like old reflections: you will save what you can by pretending, she seemed to tell herself, and infection will pass you by. She could not arrest what had entered their house. She could only record it in the private ledger of her mind, preserve the image of her husband as he used to be and refuse to touch the new one when it passed by her rooms.

One morning in August Nathaniel called a gathering at the main house. He set a table in the parlor and placed papers before him; those who were there would say later that he moved like a man who had found a new voice, neither small nor triumphant but something else—a voice with weight. He signed the documents with a hand that did not tremble. He signed emancipation papers for sixty-three men and women who had toiled on his land. He spoke afterward, a speech so raw that it made several present step backward, and a wind so sudden that no one could explain it rose as if the room itself were inhaling.

The declaration was not simply legal; it was sacramental. Nathaniel declared, to a county that had set itself up on the taut wires of “property,” that the idea of possessing another human was an error of such magnitude that it required correction. He did not couch it in the language of abolitionists; he said simply that he had seen things he could not unsee and that truth had made a call on him. Some laughed; some cursed; a few, mostly women, wept. A small number attempted to force him back into what they called sensibility. They died within weeks.

The pattern tightened around Bellwood. Doctors who tried to explain the bodies, ministers who tried to exorcize what Nathaniel called the “delusion,” even men who came with weapons to drag Emmanuel from the property—these men died in ways that could not be entirely explained. Some were found with their eyes turned inward as if they had been given visions that ate them from the inside; others perished in accidents that read as mortal mockeries of their hubris: one drowned in a saucer-deep bathtub that held no sign of drowning from water-related issues, another was found burned in a room where the hearth had not been lit. Rumor, as efficient as any disease, turned to quarantine. Official records began to shuffle as though a great hand were rearranging a ledger. The name Bellwood disappeared from deeds. The local post stopped bearing notices to the estate. The plantation became, in official memory, a blank.

No state conspiracy can completely erase private journals. Margaret, after the chaos, wrote in a careful copperplate that refused sentimentality. She documented address, date, small precise facts: how Nathaniel would rise before dawn, how he would walk to the clearing even after the day broke and sweat ran down his back like a confession. She wrote of the east room which he had locked and where he spent hours wrapped in symbols painted on the walls. She wrote of the final night as plainly as she could, because sanity, when it has been shaken, often seeks a structure in which to land.

The morning Nathaniel vanished, Margaret woke to the sound of drums, more urgent than before, the rhythm of music that had always felt like breath. She followed, at a safe distance, a thing that women do when they cannot protect: they watch. She saw him unlock the east room and disappear into it with Emmanuel; she felt as if a veil had been dropped across the world then and there. The rest is recorded in the human ways people tell stories: lights, chanting, a flash that was neither lightning nor hearth, the silence afterward. Morning revealed an empty room where the altar had been. It revealed folded robes. It revealed nothing about the men who had left with the night.

The freed men and women of Bellwood were gone. Nathaniel was gone. Emmanuel was gone. The sight of the empty cabins made the heart in a man’s chest a question. Margaret barred the east room and never entered it again. She moved through the rest of her life like one who had watched a miracle and was duty-bound to forget it. Officials accepted an explanation: Nathaniel had run into the woods and perished. It sat fine with people: ghosts are expensive, and society prefers to spend its credulity on markets rather than mysteries.

So the land at Bellwood reverted to uncultivated ways, to a silence that people conferred with lamps rather than voices. Families who bought the property later reported it oddities: a sound like distant drums on certain nights, the smell of smoke in rooms that had no chimneys. Children told their parents that sometimes, at dusk, a thin figure in white could be seen walking the path that led to the clearing. The house survived until the war, when a fire took the east wing. The official reports called it carelessness. The whispers called it retribution.

Time, with its stubborn appetite, did to Bellwood what it does to all things: it turned the place into a set of ruins and then into silence. But stories traveled differently. People displaced and freed told versions of the same thread in cities north and in pockets of ports in the Caribbean. Some said Emmanuel survived and built a shrine where the enslaved could come and learn without fear. Others said Nathaniel embodied the border between worlds, an odd apostle whose accent shifted with the weather. The versions multiplied and selective memory took what it liked.

This is the place where things often get flattened by history. People take a delicious, dangerous story—one that threatens the comfort of generations—and bury it under the measure of acceptable narration. They alter deeds, burn papers, write polite notes that describe unknown illnesses. There are reasons for that, which have to do with power and with the price society is willing to pay for a belief. Power insures itself by selecting which stories may the public hear. A master worshipping his slave unsettles a principle that built an economy. That principle, when it senses a leak, closes ranks.

But stories, like seeds, find soil in unlikely places. They sprout there. And what the oral traditions preserved, what Margaret wrote in ink too sharp for the time, what a doctor’s journal described in terms he did not understand—these fragments survived through splintered channels. Families kept letters folded in albums. Midwives told tales by hearthlight. The men and women who came through the South carried the myth of Bellwood with them like a talisman: a terrifying parable of how fragile authority can be when confronted by knowledge that refuses to be owned.

Many would read this tale and decide its core thing is supernatural. That the deaths were spells, and the storm that came like Shango’s anger was a god’s pleasure. Others will see in it metaphors and social dynamics: a man whose education was his perfect undoing, a society so brittle it could not contain a single act of contrition. Both readings are possible because both are human ways of arranging uncertainty. What I want to suggest, more than explanation, is consequence.

Nathaniel’s public step was, in a way, a refusal: a public renunciation of a century’s assumption. He sacrificed what the world calls property to own what the world will not grant name to: the idea that another person is fully human, that knowledge is not only contained in books or whitened pulpit speech. He did it badly, perhaps, because repentance often looks like madness when it is sudden. He did it with an urgency that was neither patient nor strategic. If you look for neat moral architectures you will be disappointed: the man who attempted to change his life did so from a confused, hungry place that asked more of him than the world could allow.

Emmanuel himself is less an enigma in this telling than a crystallization. He is a keeper of memory, a carrier of lines and songs that survived the Middle Passage. Entering Emmanuel’s mind requires accepting that certain cultural structures were alive on the plantation in ways white society refused to acknowledge. He practiced what he knew, and people followed him not because of force but because of recognition; recognition is a strong glue. He did what any faith’s keeper does when pressed by danger and injustice: he tended his people. He used what he had, and what he had was not merely words but a network of things older than their captors’ justificatory scripts.

If the orishas in this story are literal, they are as literal as any god a human being worships. If they are allegorical, they still possess the force that allegories do: to reorder a heart. The storm that arrived when Nathaniel made his stand carried the grammar of the story longer than any manual could have. People who were there claimed different things; witnesses later denied certain details when convenient. That is the way memory works when reputation is at stake.

I have been careful—perhaps to the point of dryness—not to import modern definitions of culpability onto characters who were by all accounts living inside an architecture of violence. Nathaniel did not become innocent because he renounced violence; he had profited from a system that did not allow him to know the daily moral economy of exploitation. Nor does the fact of his change absolve him. Emancipation as a private act does not erase the centuries of harm; it is a gust of wind that might help reroute a long, entrenched draft. The people who were enslaved did not “need” Nathaniel to rediscover their humanity. Their value existed without his consent. The drama is that he, a man born into the conviction of ownership, had to be forced—by a certain education, by fear, by something older than him—into acknowledgment. The drama is that the price he paid was disproportionate to what anyone should have demanded.

Margaret lived on into decades shaped by war and rebuilding, carrying an archive of private facts that made sense only to her. She told no one everything; there are things wives keep to themselves not to conceal but to preserve memory intact. The rest of the country moved on in convulsions of union and division. Bellwood’s hill seemed to the new generation just a place where trees had begun to fill in what men had once opened. Old columns stood like ribs of a story that had been told and then half-remembered.

In other tellings, Emmanuel crossed the water north, or sailed back to a homeland that did not need the broken merchandising of empire to give it form. In some, he taught in cities where freed men and women came to learn without fear. In others, he walked into a forest and became part of the earth. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive because stories are not always required to submit to one ending. They are testimonies: of survival, of the way knowledge moves under surveillance and finds new mouths to inhabit.

I do not mean to tie this to the supernatural as the only way to make sense of what happened. History is often stranger than explanation, and people will do what frightened people do: they will write accounts that straighten curves into fists to make moral sense. But perhaps the deepest truth here is quieter: a man confronted with an idea that undermined his livelihood chose truth over convenience. He acted not out of courage in any heroic register, but out of a hunger to align his life with something he had discovered. In doing so he became an outcast. Outcasts often burn brighter, for the simple and terrible reason that they are no longer bound by the habits that make a society run.

What echoes most clearly through the telling is the persistence of those who keep memory alive in spite of power. The songs the slaves sang were not simply entertainment. They were a ledger of belonging. They kept codes, they preserved prayer. Emmanuel is a figure partly composed of those who teach in kitchens in the deep night, of healers who do not advertise their medicines, of ritualists who memorize lineages and pass them along between broomsticks and bread dough, between lullabies and the clatter of wooden cups. Those hands are the ones that carry the future when the world thinks to erase it.

If there is a humanistic ending to be salvaged from the strange and terrible season that came down on a small plantation in Mississippi, it is this: a human being can be unmade and remade by encountering truths that contradict what his life was built on. A society built on lies will defend itself with violence when a single instance shows those lies to be lies. The history of power is a relentless record of those who sought to protect their illusions. But history is also a book of margins; in those margins people preserve what can be preserved. The freed men and women who vanished from Bellwood—whether they walked into the world and lived under new names, whether they returned to Africa, whether they gathered in secret in northern cities—did what their ancestors did to survive: they kept knowledge alive.

In the end, the story I have tried to tell—leaning as it does on both rumor and recorded grief—is an invitation to twin acts of courage: the courage to look honestly at past wrongs and the courage to value the forms of knowing that exist outside official sanction. If Nathaniel’s choice seems at once tragic and redemptive, it is because redemption in the human register is never free. It exacts cost. It asks of the privileged to relinquish comfort. It asks of the oppressed to trust that the world can change enough to honor their personhood. Sometimes, in the most surprising ways, such things happen.

The columns of the old house still stand in some memories as tidy white ribs, the magnolia trees a soft canopy over a field that has since been cut and resown. At dusk on certain nights—if you pass by and believe yourself open—you might hear on the wind the faint beat of a drum. It could be the sound of roots remembering the rain. It could be the echo of a man who once owned a plantation and lost himself to an idea. Or it could be that some things, once spoken aloud by a circle of people beneath a clear sky, never quite go silent. They keep pulsing through the world like the stubborn heart of a city, keeping rhythm with those who will, in time, learn to listen.

News

End of content

No more pages to load