When Patsy and Poly were children, Sally had been their attendant and companion; she had accompanied them to the markets of Paris, learned the sound of another language, and cradled small bodies in a city where talk of equality had different meanings. In France, some of what defined a person’s life in Virginia could be suspended. For a handful of seasons Sally had watched the way people moved without the constant shudder of owning or being owned. The notion of being allowed to choose—so foreign and so fierce—had lodged in her like a seed.

But seeds do not always take root. A promise, once given, can be a stony thing.

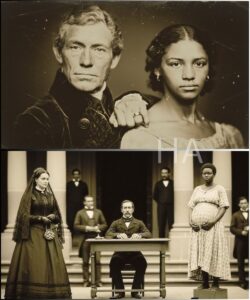

When Jefferson spoke to her after those seasons abroad, when he asked her to return to Virginia with him, he did so as a man used to being obeyed. He spoke of privilege: not freedom, he told her, but a gentler fate at Monticello, a life shaded from the fields and closer to the house. He promised that her children would be cared for, that they would be received differently from other enslaved children. He promised that their names would be kept, that in a way, within the house, they would not be invisible.

Sally listened. She had a child inside her then, small and restless. To stay in Paris might mean freedom—but what was freedom without a network of kin, without a bit of support? To stay there alone, with the world wide and indifferent, would require a reckoning she was unsure she could survive. Her mother’s eyes had told stories of long nights and quick hands. The Hemings would have to live unmoored in a strange city.

“You would not go back,” Jefferson said once, standing at a window over the garden as winter turned. The afternoon was thin; the shadows were long. “But I cannot remove you. You know the law. You know the country.”

Sally said nothing. She had seen how law could sterilize the most urgent human truths—how the edges of a person’s life could be defined in ink. She had seen the way her mother’s children were counted like inventory. When she thought of that child in her belly, she thought only how she would let that child sit at the table when the world asked otherwise.

“I will not ask you to be anything less than you are,” Jefferson added, as if he were a steward arranging objects. “You will have certain comforts. Your children—when they are born—shall be raised with some of the advantages that other children won’t have.”

These were the contours of a bargain not freely made. The bargain contained a promise with a clock in its chest: the vow came with a condition attached, a life she would have to endure in exchange for a measured mercy. She took the bargain because, at the center of it, there was survival for the child she would carry. She took it because she could not see another viable map to safety.

Years passed. Some children lived, some did not. The names were recorded in Jefferson’s books like events that did not belong to him: entries in a ledger, margins dotted with the practical hum of plantation account-keeping. Sally buried two babies in the coarse soil of the Hemings burial yard and watched the rest grow into a life threaded by precarious privileges. The children—Beverly, Harriet, Madison, Eston—walked between worlds: they learned to read the faces of visitors, to hide their emotions in a glance, to keep the tone of their voices soft when strangers were near.

Within the house, their presence was both a secret and a public knowledge. The white visitors who came to dine saw them at the table occasionally; they watched the way the children’s eyes mirrored those of the master and either pretended not to notice or grew polite and careful at the thought of scandal. The black workers in the fields noticed the different terms by which Sally’s children moved through the plantation. They saw that Beverly was apprenticed to the carpenter rather than lashed into fieldwork, that Harriet had tasks that required, in a strange way, less brute force. Yet no one—no one who wished to keep what they had—uttered the words that hovered like a fog.

A man named James Callender blew away the fog with a breath like a torn bell. He had been a partisan agent, a powder keg who once aided Jefferson and then turned against him. In the Recorder he drew a portrait in charged ink: the president whose public principles spoke equality while his private life lived another law. He gave the plantation its name in print, named the mistress who had died, the children who grew in the hush.

When the paper folded into others and the cabbages of scandal were carted onto the front lawns of conversation, Jefferson maintained a silence that was itself an argument. He was a man who had constructed sound defenses in law—he had built his own empire of rhetoric—and his silence functioned as a different kind of fortress. He never confirmed; he never denied. He did not move to sell those most entangled with him; he did not fling them into the wind. Instead he endured the cry.

Sally watched the public performance from her sitting room. Visitors brought laughter and questions and the genteel disdain of people who had never had to survive by half-promises. The wagons passed like rumors. Her boys and girls grew under the peculiar status of being both property and, to those who knew the truth, intimately connected to the family that ruled the town. Within their schooling and their labors, they learned a harsh arithmetic: to live as Hemings meant counting the costs of the truth in silence.

“What would you have me say?” Jefferson asked his niece once, in a voice that had the calm of a man who had learned to unspool his life into acceptable folds. He had been pressed to respond by dramatised letters and public attack. “Do you think any version of truth would be kind to the family?”

His niece, who had kept him in her adolescent awe, stared at him and then away. “He is a man who valued his reputation above everything,” she said in private conversation to a cousin. “This is what he learned to protect. But some things cannot be shielded from time.”

Time did not move in favor of secrets. It accumulated on the porch steps; it settled into the bones of people who had expected different courses from their lives. Within Monticello, there were nights when Sally could hear Jefferson’s study lamp turned low at the hours when sleep is most fragile. There were afternoons when he would walk in the garden and pause, looking at the younger daughters and at the Hemings children, a man contemplating his crafts and inconsistencies.

The plantation’s contradictions were not abstract. They sank into meat and cloth and the way a child’s laughter could cause a room to go quiet. The Hemings children understood how to translate attention into motion that made them safer. Madison, who looked like a tiny ledger in the world’s accounting—reserved, observant—kept a journal in his head of the small mercies and the long harms.

One evening, when James Callender’s words had been echoed and re-echoed by men who traded in reputation, the household gathered in the room that served as Jefferson’s study. The house held its breath like a hand held over a candle. Jefferson read a letter and folded it and set it down. He did not speak of himself; he spoke about debts, about falsehood, about the necessity of steadiness in the republic.

Sally sat at a distance, her hands folded in her lap. She had learned the rhythms of these gatherings and how to make herself like a quiet instrument. Patsy came to sit beside her. They both listened because the world they moved through was measured by how other people defined propriety.

When the study emptied and the night came, Jefferson walked the long hallway that connected his room to the room where Sally lived. He paused before her door, as if performing a small duty of the household. He did not speak. He touched the latch and passed. The silence between them was not mere absence of sound; it was their pact, their history, a complicated ledger of favors and obligations.

Years accumulated and the children grew. Beverly left when he was young, and simply did not return. Harriet moved every so far away, given money and a geography that allowed her to live a life that was half-hidden. Madison and Eston were listed in the will among the names to be freed at a certain age. In death, Jefferson executed a form of fidelity to the promise his voice had once made in a foreign land—he left a few to be freed. But he did not leave Sally free, and in that omission the ledger grew heavy with omission.

That omission became an ache in Sally’s chest. She had watched the children bend toward sunlight and then be pushed away by the shape of law. She had been promised a thickness of life that the world would not allow. When the estate’s debts were tallied and the prospect of Monticello’s breaking spelled the danger of sale and dispersal for the enslaved people who lived there, Sally felt the ground shift under her feet.

After Jefferson died—on a summer day when the nation remembered the date of its birth—Sally was not handed a legal certificate. She was not permitted the paper that would turn her status into the world’s new ledger. Instead she was permitted to leave, informally, with her children. It was a small mercy by the standard of the law, a larger mercy by the standard of her survival.

She left with a few bundles, with children grown and learning how to be in the world. She carried within the short thickness of her life the knowledge that she had endured and had loved within the constraints she had been given. That love—because the word insists upon being used, flawed as it may be—had not always been radiant or voluntary in the ways the pamphlets of romance would describe. It had been survival shaped into care. It had been a kind of daily close attention: nursing a fevered child, smoothing a hairline, offering a corner of the house as a refuge.

In the city where she moved—a small, brighter grid of streets—Sally lived in a rented room near the market. The children found small employments, and for the first time in her life Sally possessed the illusion of choice. She walked the streets without the yoke of the house’s watchfulness. Her face, in the last census before she died, would be recorded in those narrow categories that attempted to bind people with words like “white” or “mulatto,” but she had long known that such boxes were made by people who wanted to simplify a messy world.

She died quietly some years later, surrounded not by pomp but by the small riches of neighborhood and the children who had been hers in everything but the law. Her last days were not dramatic. They were the steady rhythm of someone who has made a life from all the small things she could command: a pot kept warm, a child’s arm that leaned on her body, a letter that was saved.

The public would tell other versions for decades. For the children and their descendants, the choices made by the world were even more consequential. Some crossed the color line to claim the rights that pale skin allowed; one changed his name, married into white families, and let the Hemings lineage recede like a stone dropped into deep water. Others kept the name and kept the memory, speaking of it in the hush of family rooms. Madison Hemings, who had been freed and chosen to remain in Virginia, would one day go public with what he remembered; his voice, when it spoke, would be a measure of his courage. He would tell a reporter that his father was the president; his words would be dismissed as gossip for years, until science decades later put its own, hard instruments to the question.

This was the thing about secrets: they are patient, and sometimes they are overturned by facts that cannot be unpicked by denials. When the scientific tests came—many generations after the soil had taken footprints and the houses had burned—DNA would indicate what the hushed talk at Monticello had long implied. The conclusion was not simply a scandal; it was an accounting. It meant that the great man’s life was not a single tidy story. It meant that the country’s memory had been selective.

In the years after, the museum at Monticello added a plaque; the rooms that had once been painted in omission now housed narratives that included the Hemings. People came and read the updates with the unassuming curiosity of tourists, and some left with a small discomfort that is good for a republic. There were those who would not be satisfied that a stone could show the full depth of an old hurt. Others, descendants of Hemings and others who had been bound, formed knots of memory in gatherings and began to map out their shared past with a painstaking tenderness.

At a conference some years later, an elderly woman stood at the podium and read a short passage. She was a descendant of the Hemings line through marriage—her face a quiet constellating of what had passed. “My great-grandmother taught us how to stitch,” she said. “She taught us how to sew by candlelight. And she taught us how to tell the truth, even if the truth was only told quietly in the kitchen. We have been learning to hold our stories in our mouths like small, warm things.”

A hand came up in the front row. It belonged to a historian who had spent a lifetime parsing Jefferson’s letters. “Is there not a risk in retelling such things? We risk making a villain of parts, not seeing the man whole and contradictory.”

“Perhaps,” the woman said. “But there is no villainy in naming harm. There is healing in truth.” She looked to the faces in the room—some white, some black, some of an indeterminate shade that was a map of who this country had become. “We do not want to tear down. We want to learn how to build differently.”

In days that followed, the museum added guided tours that spoke of the Hemings with care, and schoolchildren who had learned patriotic songs in earlier years learned now to ask sharper questions. They were taught that the history of a country cannot be embodied in a single man without admitting the multitude he contains. They were taught to look at documents and DNA and to listen to the stories passed from kitchen to attic, from grandmother to grandchild, to locate the truth where it lived: in letters, in bones, in the creased faces of those who had survived.

It was not a clean redemption. No list of facts could make the wrongs right. The legal freedom that some of Sally’s children received did not return the years of compulsion nor the quiet degrees of humiliation that were woven into a life lived under someone else’s orders. Yet acknowledgement gave some breathing space. It allowed conversations that were otherwise locked to enter into the light, to be argued and held and weighed.

In the end, the most human moments were small and private. A descendant of the Hemings once met a descendant of Jefferson in a museum hallway. They exchanged a brief nod and then spoke slowly, as people who must measure each sentence when history is close. They did not seek culpability in one another; they sought recognition.

“You are the family of the house,” the Hemings descendant said.

“And you are the family who kept the house’s reality,” the Jefferson descendant replied.

They both smiled, an awkward, real arc. “Maybe that is enough for now,” the Hemings descendant said.

“No,” the Jefferson descendant answered. “It is not enough, but it is a start.”

They walked away in different directions, their steps the ordinary measure of lives that had to continue. Outside, the Monticello fields turned with seasons, a wheel that could not reverse.

Sally’s story, when told now, is not a simple tale of conquest or one of private affection. It is both a record of power’s reach and of a woman’s stubborn will to survive. It is about a nation that had built its ideals on paper and then applied them unevenly. It is about how descendants carry that unevenness in their bones and how they choose—generations later—to speak or not to speak, to pass down names or to bury them.

In a small room lined with threadbare curtains, a bedstead, and a single candle at the window, Sally once bent over a basket and mended a shirt with the kind of patience that clause and phrase could not measure. She hummed quietly while the evening cooled. Above the door, the sound of the Monticello bell marked a day’s end.

The candle’s flame leaned without blowing out. On the table near her hand lay a small piece of paper, creased with notes she had kept—names and dates and the odd observation about the weather. The paper smelled of dust and lavender. She smoothed it once and then folded it again, and in the act of folding she did everything a life can do: she pressed memory into a thing small enough to be carried, to be kept.

When others opened such folded papers years later, when historians read and scientists measured, the portrait of the past had more parts. The story widened, not to exonerate or to damn without balance, but to let the nation see the human beings who had lived in defiance of its simplest proclamations. Sally’s life now sits inside a complicated public memory: a figure who teaches about the costs of power, about the courage of ordinary endurance, about the ways a promise can be made in one place and broken in another.

At the edge of the house’s garden, a sapling grew new leaves each spring. People who read the plaques and walk the paths see both the house and the shadow that has long accompanied it. They study the maps and the letters and the names sewn into family trees. And in the quiet corners, where voices are low and honest, they tell the smaller stories of what it meant to keep a life together by stitching the torn pieces into something that resembled a life at all.

Sally taught her children how to mend and how to account for a world that could be kinder in its private moments and brutal in its laws. She taught them to remember. And in the remembering there is a kind of repair—imperfect, ongoing, but real. It is the repair of a people who insist that tomorrow will be different because they have looked clearly at yesterday.

The river still runs, even when frost takes the banks. It keeps its course. People stand on its edge and trace its line, and some of them recognize that freedom is not a single crossing but a series of small steps that make a path over time. Those steps are what Sally left: not the destinies she had been denied, but the quiet instruction of survival, and a legacy that, at last, the country had been compelled to acknowledge.

News

🌟 MARY’S LAMB: A STORY THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

CHAPTER III — THE SCHOOLHOUSE SURPRISE Spring arrived, carrying with it laughter, chores, and lessons at the small red schoolhouse…

The Emerson Family’s Church Was Built Over Something That Never Stopped Moving

The cemetery curved around the church in a protective, patient arc. Graves crowded up to the sides and front. But…

Elderly Widow Shelters 20 Freezing Wrestlers, But Next Morning…

They came in columns, not without order but not with parade precision either; boots punched the snow in steady measure….

Millionaire opens his bedroom door… and can’t believe what he sees.

When David stepped from the doorway the next moment—feeling, inexplicably, his chest empty of the familiar acid of anticipation—Laya looked…

She ran to the elevator fleeing her ex — unaware the Mafia Boss was inside, when the doors opened…

Strong hands caught them. The man who held them looked like he belonged in the kind of photographs that had…

“Sir, that boy lives in my house”… But what she revealed next shattered the millionaire

Inside, the living room was dim and careful. Clare—Amelia’s mother—was there with a smile that didn’t touch her eyes. She…

End of content

No more pages to load