Anderson’s name moved through letters and whispered prayers the same as rumors. In the Union camps it became a shorthand for excess. There were officers who kept lists and maps of his raids, and scouts who treated his possible appearances like weather warnings. In the parlors and kitchen stoops of townspeople his name was a ghost that invited people to cross themselves or look quickly toward the closed shutters. But that dread did not stop some men from following him. Vengeance has a gravity; it pulls people toward those who can give them an outlet. A farmer who had lost sons to a Union patrol might see Anderson as the only instance in a life otherwise ruled by impotence where he could watch someone act.

The last months of his life were not the crescendo of a monster’s score but the sagging exhaustion of an overworked instrument. The raids grew bolder in the summer of 1864, fed by freneticness and a sense that time itself had narrowed into a tunnel with only one exit. Men grew careless in different ways: some through intoxication, some through confidence. For Anderson there were another series of losses that fanned into fuel—letters from a wife he had not seen in years, a home burned by troops who could not distinguish houses from hideouts, and a perpetual ache where a child’s face once fit in memory. Rage feeds on absence the same way hunger feeds on bread; it amplifies, it becomes fantastical, it rewrites the ledger to remove any entries that had once been tender.

Albany was a place of low hills and faster streams, a town that had learned to be watchful without being walled. It had no massacre to boast, only accumulative scars: an orphan here, a burned barn there. The Union scouts and informants had been patient, watching the black riders’ loops and circles on the outskirts, mapping the geometry of their movements like an old farmer maps the wind. For days they tracked Anderson’s shadow-caused footprints, buying an inch at a time of respite for the innocent. The men who ran those scouts were not interested in spectacle; they wanted an end that would not be messy or public enough to turn the man into a martyr.

The morning of the ambush, dawn cut low across the prairie, turning the dew into a brittle glitter. The Union men camouflaged themselves along a rise and behind split-rail fences, their rifles tacked carefully into the crooks between their knees. They were not young by intent; war had made many of them into halves of men who had been boys once. Their orders were precise. Kill without excess. Take no scalps for trophies. Let the body testify that law can end lawlessness.

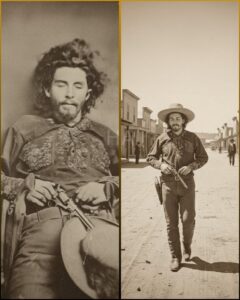

Anderson rode as he always had—full throttle, eyes like a pair of matches set to ignite any tinder around them. He expected a world that answered his fist with flight, not with a mirrored fist of organized discipline. His horse was a great bay, muscled and white-eyed from too much fear bred into its blood. He had the braids once again—trophies collected from the friction of his campaigns—braids no longer attached to any proper head but looped in on themselves and fixed around the horse’s mane. They flicked like the weather vane for his temper.

At first it looked as if he would ride on free. The riders had the habit of moving fast and unpredictable, scattering like startled crows whenever they met resistance. But the Union men had the advantage of position and patience. A volley cracked across the field, and horseflesh screamed and fell. Men toppled from saddles. The air tasted of smoke and dirt. Horses bolted. Anderson, who had never been distinguished by prudence, leaned into the chaos, pistols belching until the metal within them cooled. He fired as if the act itself was proof against the emptiness he felt. He fired until the thud of rifles pushed the sound out of his mind.

When he fell, he did not land with a lyric or a soliloquy. He tumbled gracelessly, his horse pulling away in a panic and leaving him small, ridiculous, and mortal on the grass. The Union soldiers closed in, cautious. There was no grand exchange. They found him wide-eyed and slack where he lay, like a child at the end of a tantrum, only the tantrum had been decades long and had cost hundreds of lives. They stripped him of his pistols and the braided trophies, which now seemed grotesque for their quietness. Someone pinned a paper to his ragged shirt: “This is the remainder of Bloody Bill. He will kill no more.” The paper was as ceremonial as a bill of sale.

The crowd in the town gathered. Men spat their relief. Women who had closed their blinds for weeks came out with the stooped, tentative body language of those who have been holding their breath and forgot how to exhale. Some crossed themselves. Some hissed curses that their tongues had kept warm. For a handful—mothers who had lost sons, a farmer who had seen his fields burned—the sight of the man’s stillness did not translate into joy. It translated into a complicated, wobbling blankness, a feeling that the ending did not parcel out the way they had imagined.

Jesse James stood at a distance, a young knot of shadow among the onlookers. He had watched the man he had followed fall with a look that was both hollow and searching. Something inside him seemed to shift. He had learned a type of politics under Anderson’s tutelage—the calculus of a life that must be paid for in force—but he had not been given an explanation for grief, and the solidity of that omission pressed against him now. For the first time he felt the shape of the future as less of a map and more of an opportunity to step away.

You cannot write the entirety of a life into one scene. Anderson’s death did not produce an immediate conversion of Missouri to saints and choir-singing. Violence was not a disease that a single body could contain. But endings seed something else. They release a spectrum of responses.

There was a woman whose name was Liza March, whose tragedy had been particularly private. A farmer’s wife and a midwife, she had been rising early the day Anderson’s men had come through her county. They had taken a chest of linens and trampled a gravestone in the yard. Her husband had been taken by a patrol months earlier, and letters from him were as thin as breath. Liza had seen Anderson’s shadow crossing the corn and had watched, through the slit of a shutter, men with faces like unmade beds. She had watched a boy—no older than twenty—cry when the riders took his guitar and smashed it; she had watched an elderly neighbor fall and not be helped. When the news came that Anderson had been slain, Liza walked to the site where the man had been laid out and stood with her hands clenched. She expected a simple triumphant feeling. What she found instead was a nausea of recognition: the man’s face was younger than the stories, more human than the rumors. She realized then that the story she had held as a closed logic—he acted, therefore justice—was not a closed logic at all. In it, she saw her husband’s empty chair and her own hands and the tasks that remained: to bury and to heal and to speak for the dead in ways other than revenge.

Others took different lessons. Some of Anderson’s followers rode off and laid down their weapons over time—unable to deny the weight of the ledger they had added to. Others hardened further, deciding that the world could only be righted by those willing to make final judgments. Jesse James left Missouri in the years that followed and became a name in his own right, choosing paths that would make him a symbol of a different kind of restlessness. His life would loop and twist in ways no one could have predicted the morning he watched Anderson fall.

Missouri continued to bleed in its own slow way even after the war’s final cannons were silenced. The land was not a body you could sew back together by decree. Fields still bore the scars of trampling and fire; houses still tended to their broken panes with the patient economy of people who know the budget of grief. The question the countryside asked itself most honestly was not “Who killed Bloody Bill?” but “How do we live again?” That question would hold the state for decades. It would be asked in little gestures—the mending of a child’s jacket, the planting of an orchard—and in the larger ones: in the slow reclaiming of law and the making of treaties between neighbors who had been enemies.

There is a moment in many grieving processes where the intensity of loss begins to dull and leave room for something else: for memory to be rearranged into narrative not driven only by the force of outrage. For Liza March this meant returning to midwifery. She went from house to house and taught other women to stitch and to deliver, and she learned to fly small acts of compassion like flags in place of the braids that had once been tied to horses. She passed on stories of men who did kind things—one who had once helped fix a well, one who had shared bread in a winter—and these stories had a strange, restorative effect. They did not erase the wounds but they made the cost of human life tangible in its many forms.

Jesse James would be hunted and remembered and mythologized. People carved out versions of him to justify what they wanted to believe—some called him a Robin Hood, others a thief—each version refusing certain facts like a child refusing to eat vegetables. But even he, in private, wrestled with what he had seen: the hollowness in Anderson’s final stare, the way the man’s fingers kept their shape even in death. These images were not easily cast into the tidy moral boxes people desired.

Time does something peculiar to names. It sharpens them into icons and then chips away at the edges until they fit different pockets. Bloody Bill Anderson’s name would linger in taverns and in the mouths of children as a bed-time threat for a generation. It would also become a cautionary tale in the hands of preachers and teachers about the corrosive logic of unending vengeance. The same event, repeated in memory, becomes a mirror for the concerns of later years: a sermon in one decade, a ghost story in another, a short-handed moral in yet another.

History likes a neat question: was he made by war or did he make war monstrous? But human lives resist such easy dissolutions into thesis statements. William Anderson was both a product of the violence he inhabited and an agent of further violence. He had choices in how he could have contained his pain and how he could have returned to the small domesticities that once defined him. He did not choose those options, or he chose not to for reasons tied up in personal traumas and in the cultural atmosphere of the time. Neither verdict absolves nor fully condemns. It is enough to say that the man’s life was a series of decisions whose consequences spilled into the lives of others.

In the years after his death, the towns rebuilt in a slow modular way. They planted shade trees that grew into larger shadows than any man might cast. Children who had watched fires were taught to play under the same sycamores where raids had once passed. The land slowly softened the scars as land does; it accumulated new patterns of hay and footing and laughter.

There were, of course, no miraculous reconciliations. Men who had once fought on opposite sides buried their own grudges in the ground and carried others at odd angles like tools. Laws were written, disputed, and then enforced with uneven enthusiasm. Apologies arrived sometimes, tentative and awkward, sometimes never at all. But within households there were quiet acts: a neighbor helping another plow an in-law’s small plot, a woman giving a loaf of bread to a man whose hands still trembled from a fever brought on by relentless grief. These small acts did not cure the past but they kept the present bearable.

When Liza March finally grew old, she would sit on her porch and watch the grandchildren of men who had once ridden with Anderson learning their own chores. She would tell them one story about a man who had once fallen from power and the way the town had reacted. She would say, with the gentleness of one who had watched both rage and tenderness, that violence may make the first impression, but the labor of rebuilding is equal to any battle. Children listened because she had a voice that was honest and because she seemed to carry in her knuckles the same kind of toughness that keeps a home standing.

Jesse James’s life unfolded and folded into other stories, and when he died, people were quick to argue what that final scene meant. A life built on ambush and calculated spectacle generated epitaphs that were quick to judge. But a surprising number of those who had known him as a boy remembered the way he would stop at broken gates and help set the hinges. It was as if, embedded in these outlaw myths, were the fragments of humane acts that people preferred to forget when the headline wanted blood.

Anderson’s grave was no shrine. It had a stone with a name and dates and a small patch of thyme growing wild around it. Sometimes men dared to bring bottles there, or curses, or flowers. The grave existed the way a bruise does—visible and then fading, the edges blurring into the surrounding skin. Time did not make his crimes disappear. It redistributed them into the archive of memory.

Years after the war wound down and the long tail of violence subsided into ordinances and rebuilding committees, some people would stand at the creek where the boy William once chased frogs and consider the astonishing fact of change. The creek had not changed all that much. It still slipped along its shallow bed, washing stones in the way rivers always do. It seemed to declare a stubborn neutrality: water flows and makes a path, it does not hold grudges.

Perhaps that was the humbler moral of the story: life continues where it is possible to continue, and where it is not, we are left to build again. The storm of Bloody Bill’s fury had passed, and the landscape took its long breath. People learned to articulate revenge in law instead of in raids. They relearned what neighborliness could be when worn like the sturdy coat given a worker. They taught their children that names should not be given the power to bind futures; that courage could be the labor of mending rather than the spectacle of taking.

Violence will always have its architects, and memory will often tell the story the victors or the senseless flowers prefer. But there is a quieter, more stubborn truth: the world heals in small increments. Gardens grow. Lawns are mowed. Babies are born and given names that are not curses. Liza’s hands continued to teach midwifery until she could no longer stand, and the grandchildren she helped keep alive grew up to be neighbors who swapped eggs and told stories at kitchen tables.

That is not a triumphant ending. It is a soft one, which to some ears will sound insufficient. But it carries within it the only kind of moral the land would accept: that the telling of a life and its final fall is not the last word on a place, and that while some men will be remembered for the worst things they did, the people around them will not be wholly defined by those moments alone. They will tilt their lives toward the ordinary goodness of mending a fence, or sewing a blanket, or showing up for a neighbor—those exacting, unsexy things that keep a community from unraveling.

In the end, the matter of whether William Anderson was made monstrous by war or whether he made the war monster remains a question historians will argue over in footnotes and monographs. But the people who had slept under shuttered windows with their children gathered close—those whose ledger of loss was the most exact and private—chose another bookkeeping. They tallied up kindnesses. They planted trees. They taught children not to repeat the precise gestures that had brought pain. From the ashes, they tried to build a town that would be, in small daily increments, less hospitable to the kind of rage that had once galloped through its streets.

So the land, with its long patience, exhaled. The ghost of Bloody Bill Anderson faded into the hills, and the sound he had made—hobbling toward a finality that was neither theatrical nor clean—became one of many echoes heard in a place where people continued their ordinary labors and, slowly, their reparations. The final punctuation to his life was less an answer than a clearing, a space in which those who remained had to decide what to do with the weight that had been left behind. They chose, imperfectly and always humanly, to try to be better caretakers of the small, stubborn things that stitch a life together after the thunder has passed.

News

🚨 “Manhattan Power Circles in Shock: Robert De Niro Just Took a Flamethrower to America’s Tech Royalty — Then Stunned the Gala With One Move No Billionaire Saw Coming” 💥🎬

BREAKING: Robert De Niro TORCHES America’s Tech Titans — Then Drops an $8 MILLION Bombshell A glittering Manhattan night, a…

“America’s Dad” SNAPPS — Tom Hanks SLAMS DOWN 10 PIECES OF EVIDENCE, READS 36 NAMES LIVE ON SNL AND STUNS THE NATION

SHOCKWAVES: Unseen Faces, Unspoken Truths – The Tom Hanks Intervention and the Grid of 36 That Has America Reeling EXCLUSIVE…

🚨 “TV Mayhem STOPS COLD: Kid Rock Turns a Shouting Match Into the Most Savage On-Air Reality Check of the Year” 🎤🔥

“ENOUGH, LADIES!” — The Moment a Rock Legend Silenced the Chaos The lights blazed, the cameras rolled, and the talk…

🚨 “CNN IN SHOCK: Terence Crawford Just Ignited the Most Brutal On-Air Reality Check of the Year — and He Didn’t Even Raise His Voice.” 🔥

BOXING LEGEND TERENCE CRAWFORD “SNAPPED” ON LIVE CNN: “IF YOU HAD ANY HONOR — YOU WOULD FACE THE TRUTH.” “IF…

🚨 “The Silence Breaks: Netflix Just Detonated a Cultural Earthquake With Its Most Dangerous Series Yet — and the Power Elite Are Scrambling to Contain It.” 🔥

“Into the Shadows: Netflix’s Dramatized Series Exposes the Hidden World Behind the Virginia Giuffre Case” Netflix’s New Series Breaks the…

🚨 “Media Earthquake: Maddow, Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Cut Loose From Corporate News — And Their Dawn ‘UNFILTERED’ Broadcast Has Executives in Full-Blown Panic” ⚡

It began in a moment so quiet, so unexpected, that the media world would later struggle to believe it hadn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load