The Warm Towel

Warsaw, Winter 1943

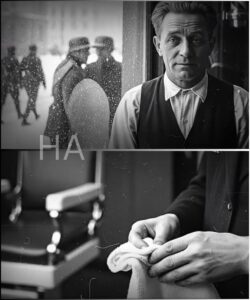

Snow had been falling since dawn, the kind that erased footprints within minutes, as if the city itself were trying to forget who had walked its streets. Inside a narrow barbershop on Nowolipki Street, the world smelled of steam, soap, and bay rum. The windows were fogged. The doorbell chimed softly whenever it opened, a fragile sound in a city accustomed to boots and gunfire.

Eugeniusz Wazowski tightened the leather strap on his straight razor and glanced at the clock. Tuesday. Ten minutes early.

“They’ll come,” he murmured to himself, more statement than hope.

He had been a barber since he was seventeen, apprenticed under his father, who had learned the trade from his own father. Three generations of hands had held razors in this room. Three generations of men who believed that dignity could survive even when the world lost its mind.

Now the chair belonged to the occupiers.

Outside, German officers marched past in perfect formation, their breath clouding the air, medals glinting like cold stars. They never looked at the shop. They did not need to. The barber was part of the street, like a lamppost or a drainpipe. Invisible. Useful. Harmless.

That invisibility was why Eugeniusz was still alive.

He wiped his hands carefully, checking his skin for cuts. None. Good.

From the back room, his wife’s voice echoed faintly in memory.

“Promise me you’ll stay invisible,” Anna had said the night he sent her and the girls away.

“I promise,” he had answered, knowing it was already a lie.

Before the Razor

Before the war, Eugeniusz had almost been a doctor.

He still remembered the lecture halls, the smell of chalk and disinfectant, the thrill of understanding how the body worked, how disease moved like an unseen army. Then the Depression came. His father died. Tuition became impossible.

“So you cut hair,” a professor had said kindly. “Medicine loses a student. Life gains a barber.”

But knowledge does not disappear just because it is unused. It waits.

And in Warsaw under occupation, knowledge became a weapon.

It began with whispers.

Typhus, people said, had appeared in the barracks. German doctors denied it. Then more whispers came. Fevers. Rashes. Quarantines.

One night, long after curfew, a knock sounded on Eugeniusz’s back door. Three short taps. Two long. One short.

He opened it to find Dr. Stanislaw Matulewicz, his former classmate, his face thinner, eyes sharper.

“You still remember microbiology?” Matulewicz asked without greeting.

Eugeniusz said nothing. He stepped aside.

The Conversation That Changed Everything

They spoke in whispers over weak tea.

“Typhus is killing our people,” Matulewicz said. “The Germans fear it more than bullets.”

“They should,” Eugeniusz replied. “It has followed every army in history.”

Matulewicz leaned forward. “What if it followed them?”

Silence thickened the room.

“You’re talking about biological warfare,” Eugeniusz said finally.

“I’m talking about survival.”

Eugeniusz stood and paced. “Doctors swear oaths.”

“And barbers hold knives to throats,” Matulewicz shot back. “We all crossed lines the moment they marched in.”

The plan took shape slowly, reluctantly, like frost forming on glass.

Not bombs. Not poison. Towels.

“Microabrasions from shaving,” Eugeniusz murmured, memory stirring. “Invisible entry points.”

Matulewicz nodded. “A cultured strain. Controlled. Limited.”

“And if it spreads?” Eugeniusz asked.

“It already has,” Matulewicz said softly. “Just not where it matters.”

That night, Eugeniusz did not sleep.

By morning, he had chosen.

The First Client

The bell rang at precisely nine.

Hauptmann Friedrich Weiss entered, brushing snow from his coat.

“Good morning, barber,” Weiss said in passable Polish. “Same as usual.”

“Of course, Herr Hauptmann.”

Weiss settled into the chair, sighing as if the war were a mild inconvenience.

“France will be better,” Weiss said conversationally. “Wine. Women. Civilization.”

Eugeniusz draped the cloth with steady hands.

“Warsaw is… cold,” he replied.

“Yes,” Weiss laughed. “Like its people.”

The razor sang softly.

Steam rose from the first towel. The safe one.

Eugeniusz worked methodically, his mind ticking through each step.

Soap. Stroke. Rinse.

Weiss talked about trains. About quotas. About delays caused by “lazy locals.”

Eugeniusz listened.

Then came the second towel.

It looked identical. It smelled identical. It felt identical.

It was not.

He pressed it gently to Weiss’s face.

“Ah,” Weiss sighed. “That’s perfect.”

Fifteen seconds.

One breath.

Two.

Three.

Done.

When Weiss left, the bell chimed as cheerfully as ever.

Eugeniusz sat down hard, his legs trembling.

“It’s begun,” he whispered.

Waiting for the Fever

The worst part was the waiting.

Ten days. Eleven.

Each morning, Eugeniusz opened his shop as usual. Each night, he scrubbed his hands until the skin cracked.

On the twelfth day, three chairs remained empty.

On the thirteenth, a neighbor whispered, “The infirmary is sealed.”

On the fourteenth, Matulewicz returned, pale but smiling.

“It’s confirmed,” he said. “Typhus.”

Eugeniusz closed his eyes.

“How many?”

“Enough.”

The City Reacts

Panic did not arrive loudly. It crept.

German officers stopped shaking hands. Restaurants closed. Inspections multiplied.

One barber down the street was arrested. A cook vanished. A laundress was shot.

Eugeniusz burned the towels at night, feeding them into the stove until nothing remained but ash. He scattered it into the river at dawn.

Weiss died screaming, they said.

Eugeniusz did not ask how they knew.

He dreamed of rashes blooming like maps across pale skin.

He dreamed of his daughters.

The Raid

The warning came from a girl no older than sixteen.

“They’re coming,” she whispered, pressing a note into his hand. “Four hours.”

Eugeniusz looked at the shop. At the chair. At the mirror cracked just enough to remind him it could shatter.

He stayed.

When the Gestapo arrived, they destroyed everything they could touch.

“Who comes here?” one agent barked.

“Officers,” Eugeniusz replied. “And neighbors. When allowed.”

They broke the sink. Ripped the floorboards. Questioned him for hours.

“You’re a simple barber,” the officer sneered. “Lucky.”

Eugeniusz nodded.

That night, alone, he shook until his teeth chattered.

Aftermath

The shop reopened.

The officers returned, wary now, inspecting towels, bringing their own razors.

Eugeniusz accommodated them all.

He never infected another.

He did not need to.

The damage had spread.

Transfers increased. Deportations slowed. Time, precious and bloody, was bought.

Anna and the girls survived.

Warsaw did not.

Years Later

Decades passed.

The city rebuilt itself layer by layer, scar by scar.

In 1991, a historian knocked on Eugeniusz’s door.

“We found something,” the man said. “Medical records. Patterns.”

Eugeniusz looked at his hands. Old hands now. Still steady.

“I was a barber,” he said.

“Yes,” the historian replied. “And more.”

That night, Eugeniusz opened the leather journal for the last time.

“I was not brave,” he wrote. “I was precise. And afraid. And angry.”

“But sometimes,” he added, “that is enough.”

The End

At his funeral, no speeches mentioned typhus.

They spoke of a man who cut hair. Who survived. Who loved his family.

And perhaps that was the truest version.

Because history remembers numbers.

But humanity lives in the quiet moments.

In warm towels.

In steady hands.

In a chair where a man once closed his eyes, believing himself safe.

News

The Widow’s Sunday Soup for the Miners — The Pot Was Free, but Every Bowl Came with a Macabre …

On the first Sunday of November 1923, the fog came down into Beckley Hollow like a living thing. It slid…

Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

The Hand That Refused to Disappear The afternoon light in Riverside Antiques arrived the way it always did: tired, slanted,…

How One Factory Girl’s Idea Tripled Ammunition Output and Saved Entire WWII Offensives

How One Factory Girl’s Idea Helped Turn the Tide of War 1 At 7:10 a.m., the Lake City Ordnance Plant…

1904 portrait resurfaces — and historians pale as they enlarge the image of the bride

The Veil That Remembered The box arrived without ceremony. It was late afternoon in New Orleans, the kind of slow,…

Muhammad Ali Walked Into a “WHITES ONLY” Diner in 1974—What He Did Next Changed Owner’s Life FOREVER

The Day Muhammad Ali Walked Into Miller’s Diner The summer heat in rural Georgia pressed down like a hand on…

The Impossible Secret of 2 Nuns who Shared 3 Male Slaves — Bishop Knew Everything

The Locked Rooms of Sacred Heart New Orleans, Summer 1843 The heat lay over the city like a damp confession…

End of content

No more pages to load