And now he was chained like a beast in a cage.

“You listen, boy,” Sorie murmured one night when the guards dozed. “What they take from us is not our bodies. Bodies are clay. What they seek is our remembering.”

Kalenda frowned. “Why would they fear memory?”

The old griot smiled a cracked, tired smile.

“Because memory survives whips. It survives ships. It survives graves. And men who build empires of silence cannot bear witnesses who refuse to forget.”

Sorie made him vow—vow with blood, vow with breath, vow with future bones—to remember everything he saw, everything he suffered, everything done to those beside him.

“You are not just yourself,” the elder whispered. “You carry the dead. And when you speak someday, the world will hear all of us.”

Three days later, Sorie Bala died of fever.

But before his final breath, he leaned close to Kalenda and whispered:

Do not surrender your mind.

When they steal your name, speak it inside yourself.

When they beat your body, let your memory sharpen.

And when they try to erase you—

become the fire that burns their forgetting.

Kalenda held those words like armor.

Then the ship came.

The Portuguese vessel was a floating tomb named The Maria Esperança, though for the souls forced aboard her, she carried no hope. Shackled from wrist to ankle, the captives were crammed so tightly they could smell each other’s fear as sharply as blood.

The Middle Passage swallowed them for eleven weeks.

Some screamed until their voices dissolved. Some prayed. Some clawed their faces until their nails tore away. Some simply closed their eyes and never opened them again.

But Kalenda whispered.

Whispered night after night, fighting the suffocating dark with syllables as ancient as dust, reciting stories Sorie had taught him, then inventing new stories to fill the void—genealogies that weren’t his but became his, memories of strangers whose names he vowed to keep alive.

Around him, others listened.

Soon they whispered too.

In the deepest pit of the slave hold, surrounded by rot and vomit and the sting of salt water on raw skin, a secret library began to form—not written on paper, but carried in tongues and hearts.

And the men guarding the ship never suspected that the cargo beneath them was collecting knowledge sharper than steel.

When the Maria Esperança finally docked at Charleston Harbor in August of 1807—mere weeks before slave importation was outlawed—only 133 of the 300 Africans who’d boarded her remained alive.

Kalenda stood among them.

Barely.

His ribs showed like cracked branches. His breath rattled. His wrists were raw. But his eyes—those eyes Edmund Hale would one day fear—were steady, burning, unbroken.

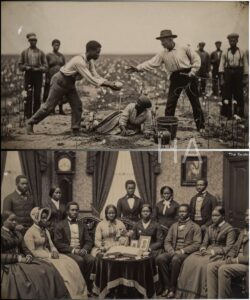

At the slave market, buyers prodded him like livestock. One man shoved open his mouth to inspect his teeth. Another slapped his back to judge muscle tone. A third tugged his hair to check for lice.

Kalenda said nothing.

Not because he lacked English—though he did—but because he refused to give them anything resembling a plea.

The man who bought him was named Marcus Bellweather, owner of a rice plantation where mosquitoes swarmed like armies and death stalked every flooded field.

And on that plantation, the first chapter of the forbidden legacy began.

Bellweather’s overseer, Tom Brannock, believed in breaking slaves the way one breaks horses—with beatings swift enough to establish authority and cruel enough to extinguish hope. He expected the new Africans to cower when he shouted.

Most did.

Kalenda did not.

On his third day, Brannock struck him across the face with a cane—once, twice—testing him.

Kalenda did not flinch.

He simply looked at Brannock, and something in that look rattled the overseer’s bones. As if this boy—this African who should have been trembling—had already memorized the overseer’s funeral song.

That night, Kalenda taught the first lesson.

He gathered six Africans who understood his tongue and whispered Sorie Bala’s vow.

“You will not forget,” he said. “Not your names. Not your lands. Not what they do to you. Memory is the blade they cannot seize.”

He taught them how to remember genealogies by rhythm. How to preserve moments through repetition. How to hide knowledge inside songs so simple that no overseer would suspect them.

And slowly, a hidden constellation of memory began glowing beneath the plantation’s cruelty.

It would not stay hidden forever.

Because the day Kalenda started teaching the children—

the path toward the 1844 incident began.

Children were the forbidden soil.

Owners feared teaching them anything beyond obedience. Overseers feared their quick eyes, their curiosity, their ability to carry ideas the way wind carried sparks.

But Kalenda had seen the future in their faces.

He saw the small girl with the scar on her cheek who hummed while working.

He saw the boy who traced shapes in the dirt when Brannock wasn’t looking.

He saw the twins who whispered in rhythm as if already practicing a song not yet written.

He knew children could become the archive that slavery could not burn.

So he began teaching them the way griots taught the sons of warriors—not with classrooms or scrolls, but with stories disguised as shadows.

While planting rice beside a boy named Harl, Kalenda murmured as if speaking to the air:

“Back home, we called this plant malo.”

Harl paused. “Malo?”

Kalenda nodded. “And the earth that fed it was older than kings.”

Later, while sweeping the slave quarters, he passed the twins and whispered:

“Let me tell you about a queen who carried her kingdom inside her voice.”

And he recited the story of a Mandé warrior-woman who never bowed, turning history into a bedtime tale.

Soon children repeated these stories, unaware they were preserving a lineage white men believed extinguished.

But Brannock began to notice something.

A shift.

A subtle electricity among the enslaved—one that didn’t smell like rebellion but didn’t smell like surrender either.

He watched them from a distance, feeling an unease that gnawed like a rat inside his ribs.

One day he caught two children speaking words he didn’t recognize—sharp syllables, unlike English.

“What language is that?” he barked.

The children froze.

Kalenda stepped forward calmly, placing himself between them.

But before he could speak, the twins lied with perfect instinct.

“Mama sings it,” one muttered. “We just copy.”

Brannock didn’t believe them entirely.

But he couldn’t prove anything.

Not yet.

He began watching Kalenda more closely.

And so the lessons moved deeper underground—into the corners of fields, into murmured rhythms during work, into the silence just before dawn when children dreamed of lands they’d never seen but somehow knew.

In 1814, Kalenda was sold.

Not for misbehavior.

For influence.

Bellweather feared him not because he disobeyed, but because he obeyed too quietly, too confidently, as if choosing cooperation rather than succumbing to it.

And because even when beaten, that terrible gaze remained—sure, unbroken, remembering.

So they dragged him in chains to a slave coffle headed west.

The march was a knife through the spine of the South—hundreds of miles walked barefoot, through mud, through hunger, through the kind of exhaustion that could fold a man into death.

Kalenda walked at the center.

He memorized.

Forty-three people shackled beside him.

Forty-three names.

Forty-three stories.

“I am not myself alone,” he whispered each night. “I am the vault that carries you.”

They taught him their histories, their mothers’ names, the villages where they had once danced. And Kalenda wove them into his mind until he could recite them backward, forward, sideways—names turned into constellations, memories turned into maps.

Two months later, the coffle arrived in Alabama.

There, Kalenda was purchased by Samuel Crawford, a man whose cruelty was not chaotic but methodical.

Where others beat from anger, Crawford beat from philosophy.

The plantation was enormous—cotton stretching like white bones across the horizon, cracked under the fists of relentless sun. The overseer, Jacob Reeves, kept meticulous logs:

Six beatings today.

Three fainted from heat.

One lost an eye after punishment.

Productivity down two percent—adjust whips accordingly.

Reeves treated the enslaved not as workers but as malfunctioning machinery.

And into this machine, Kalenda was thrust.

The first week nearly killed him.

But death was not what found him.

Something else did.

On the eighth day, a woman collapsed in the field. Sarah—small, soft-spoken, barely twenty. Her body trembled. Her breath came in ragged gasps. It was heatstroke, a killer swifter than any whip.

Reeves strode over.

“Get her up,” he barked.

When she didn’t move, he lifted his cane.

And Kalenda stepped forward.

He did not think—some truths were faster than thought.

“She will die,” he said in slow, careful English. “Shade. Water. Now.”

Reeves froze.

Slaves did not speak to overseers.

Especially not new Africans.

Especially not with this tone—steady, assessing, almost clinical.

“You know medicine?” Reeves asked, thrown off balance.

“I know bodies,” Kalenda said. “And I know death. It waits for her. Give water, or lose property.”

Appealing to profit saved her life.

Sarah survived.

And Reeves, intrigued by this strange African who understood sickness, began to pull Kalenda from fieldwork to evaluate other enslaved people.

Which gave him access.

To everyone.

To their stories, their wounds, their memories.

He would touch a fevered forehead and whisper:

“What is your true name? Not the one they use. The one your mother gave.”

He would clean a wound and murmur:

“Tell me where you were born. I will hold it for you.”

He became the quiet center of the enslaved community, a pulse of remembering, a man who taught others to store their lives like fire inside their ribs.

By 1820, he had built another network—fifty people who could speak fragments of African languages, who knew genealogies, who remembered their humanity in a place built to crush it.

But Crawford noticed something shifting.

Not rebellion.

Not laziness.

Something harder to define.

A spark.

A dignity that should not have been possible.

“Break them harder,” he told Reeves.

Reeves increased beatings.

Increased quotas.

Increased searches of slave quarters.

And one day in 1832, during a routine inspection, they found writing on a wall.

Charcoal scrawls.

A list of names.

Dates.

Wounds.

Punishments.

Women violated.

Children sold.

Slavery’s truth, written by the enslaved themselves.

Panic detonated through the plantation.

They interrogated, tortured, killed.

But no one confessed.

Crawford dragged Kalenda to the big house.

Whips.

Shackles.

Threats.

Until finally he demanded:

“Are you the one keeping record?”

Kalenda lifted his head.

Blood on his lips.

Sweat in his eyes.

Voice calm as prophecy.

“I wrote nothing,” he said.

“But I remember everything.”

He pointed to his skull.

“You can burn paper.

You can tear down walls.

But you cannot burn memory.”

The room went cold.

Reeves wrote later:

He speaks as if each moment is carved inside him. If true, then he is more dangerous than any slave with a knife.

Crawford sold him immediately.

Not to punish him.

To remove him.

And so Kalenda was sold again—this time to a plantation near Beaufort, owned by George Bellamy, a man who fancied himself a scholar of “negro psychology.”

Bellamy was curious.

Curiosity is often more dangerous than cruelty.

He brought Kalenda into his house for long conversations, attempting to study him—never realizing the lion does not reveal his hunt to the one holding the leash.

Kalenda answered questions with lies wrapped in honey.

“Slaves do not think deeply,” he claimed.

“We do not remember long.”

“We cannot organize without masters noticing.”

Bellamy believed him.

Meanwhile, the enslaved whispered the truth beneath the floorboards.

Beneath the curiosity of their owner, a new network formed—sharper, deeper, and built not only for remembering…

…but for shaping the memories of others.

For in the years since the coffle, since Sorie Bala’s vow, Kalenda had learned something new:

Memory could wound.

Story could blister.

Truth could break the mind of an oppressor more cleanly than any blade.

All it required was telling the truth so precisely that the listener became unable to hide inside ignorance.

By 1844, twelve enslaved people had mastered the technique Kalenda created.

And on a night when the Carolina wind whistled like a spirit out for answers, they met in the woods to rehearse their testimonies.

Not magic.

Not voodoo.

Not curses.

Memory as a weapon sharpened to a spear.

None of them knew that two white men—Daniel Harding and his brother William—were in those woods too.

Listening.

Absorbing.

Breaking.

When the Hardings burst into the clearing, the twelve froze.

But it wasn’t the shock that frightened Daniel Harding.

It was what he’d just heard.

A man describing the Middle Passage so vividly Harding could taste saltwater in his throat.

A woman recounting the moment her child was torn from her arms with such detail that Harding felt phantom fingers clawing at his own shirt.

By the time he reached town, he was vomiting.

By the next week, he was muttering in Wolof—the language of a land he had never touched.

And by the end of the month, William Harding had lost his grip on which memories were his and which belonged to the enslaved souls whose suffering he had absorbed.

The South panicked.

Courts intervened.

Doctors examined.

Legislators passed new laws.

Not to punish a rebellion.

But to crush a memory network they did not understand.

And at the center of the storm…

…was Kalenda Adisa.

The 1844 inquiry consumed the Lowcountry like a fever, burning through plantations and courtrooms alike. White officials had names for every kind of terror—insurrection, arson, poisoning—but they had no word for what the Hardings had endured.

How do you catalogue suffering transmitted by memory?

How do you punish a story?

How do you outlaw the truth?

They interrogated the twelve.

They interrogated Bellamy.

They interrogated anyone who had ever spoken to Kalenda.

And finally, they dragged Kalenda himself into the courthouse—heavy chains on his wrists, his ankles, even around his neck, as if iron alone could muzzle what lived inside his mind.

The courtroom was packed.

Planters sweating through waistcoats.

Doctors sharpening quills.

Politicians whispering new laws before votes were even cast.

Kalenda stood quietly, gaze steady, breath calm.

The judge leaned forward.

“You are accused of meeting in secret, teaching forbidden knowledge, and causing the mental ruin of two white men.”

Kalenda didn’t answer.

The judge struck the table. “Speak!”

Kalenda lifted his eyes.

And for a moment, no sound existed except for the tide pounding against the docks outside.

“I only told them what has always been true,” he said.

His voice did not tremble.

“It was not I who entered their minds. It was they who finally heard ours.”

A murmur rippled through the room.

The prosecutor stepped forward, jabbing a finger.

“You expect us to believe twelve slaves speaking stories caused madness?”

Kalenda responded with the smallest tilt of his head.

“Truth is heavier than chains,” he said. “Some minds break when they try to carry it.”

The judge ordered him removed.

The next day, the legislature passed a law forbidding slaves from meeting in groups larger than three, forbidding any form of “mnemonic training,” forbidding anything that smelled of intelligence held in common.

Laws made to smother one man’s legacy, though his mouth never shaped a threat.

Bellamy, shaken to his marrow, did what others before him had done: he sold Kalenda.

Not out of anger.

Out of fear.

“Your presence pulls the veil from our eyes,” Bellamy whispered on the morning the slave trader arrived. “And we cannot live in a world where we see what we’ve done.”

Kalenda was taken to a smaller plantation inland, owned by a man named Edmund Hale.

This is where the forbidden letter came from.

This is where the final fire of Kalenda’s life began.

Hale’s plantation was small—only twenty enslaved workers, fields modest enough to be managed without an overseer. Hale himself monitored the work, a man who preferred order, quiet routines, predictable lives.

Slaves terrified him for a simple reason:

He could not imagine their inner worlds.

Therefore, he could not control them.

Kalenda was brought like a dangerous dog—muzzled, shackled, warned about.

“Speak little,” the trader told Hale. “He has a way of getting inside you.”

Hale scoffed.

But that night, when he passed the slave quarters, he caught Kalenda looking at him.

Just looking.

And something inside Hale tightened like a rope.

He told himself it was nothing.

But the sensation returned every time their eyes met:

the soft, undeniable feeling that the man in chains knew him more intimately than he knew himself.

As if Kalenda could see the guilt Hale buried beneath sermons and family pride—guilt passed from father to son, a rot inherited along with the land.

The enslaved on Hale’s plantation were a quiet people— worn down by years of small cruelties, but not broken. They accepted Kalenda the way dry soil accepts rain.

He did not teach them in gatherings.

Hale watched too closely.

Instead, he taught them inwardness.

A new technique.

A private, silent, almost sacred act:

witnessing.

During fieldwork, he would murmur:

“At night, close your eyes. Remember the worst thing done to you. Speak it inside yourself. And remain standing.”

A woman named Amara tried it first.

She had lost three children—sold before they could walk.

For years the grief had sat in her chest like a stone.

When she witnessed the memory, she shook until her bones ached.

But afterward, she could breathe.

Not because the pain disappeared.

But because it finally had shape.

One by one, the enslaved learned this.

Grief that had festered now flowed.

Rage that had burned now clarified.

Fear that had ruled them now receded.

Hale noticed.

They did not walk like broken people.

They did not speak like shadows.

Something in them felt upright, centered, alive.

It terrified him.

So Hale started writing letters to his brother in Charleston. He tried to describe the unease, the nightmares, the way Kalenda’s silence seemed to vibrate like a tuning fork inside the walls.

In the third letter—the one he never mailed, the one hidden inside the plantation wall—he confessed:

When he looks at me, I remember things I never lived. I dream I am chained, that I am being beaten, that my children are taken. I wake gasping, tasting iron in my mouth. He is doing this to me. Or perhaps truth itself is doing this.

Hale became afraid to sleep.

Because every night, he lived the life he had forced on others.

He did not tell his wife.

He did not tell his neighbors.

He wrote, and wrote, and wrote.

Then hid the pages away because he feared what they made him.

He feared he was becoming human.

In the fall of 1845, something snapped in Hale.

He called Kalenda into the barn.

The door shut behind them.

The lantern’s flame shook.

“Tell me what you are,” Hale whispered. “Tell me what you’ve done to me.”

Kalenda did not move.

“I have done nothing,” he said.

“That is a lie!”

“No,” Kalenda corrected softly. “It is a mirror.”

He stepped toward Hale—not threatening, not pleading.

Simply present.

“You fear me because I remind you you are a man,” Kalenda said. “Men know right from wrong. Only beasts forget.”

Hale trembled.

“They say you haunt minds.”

“No,” Kalenda said. “I awaken them.”

The lantern flickered.

“You can kill me,” Kalenda continued. “But you will dream the truth until your bones rot.”

Hale’s knees weakened.

“No more,” he whispered. “I cannot bear it.”

Kalenda nodded. “Then change.”

Those two words broke Hale open.

In the weeks that followed, he stopped whipping.

Stopped shouting.

Stopped pretending his world made sense.

Each night he dreamt the dreams of the enslaved:

running through forest;

wading through rice fields;

hiding in swamps;

screaming into the silence of a world that refused to hear.

Hale began visiting freedmen in nearby towns, asking how they lived, how they worked, how one could set slaves free without causing ruin.

And in the winter of 1846, Hale did something no plantation owner around Beaufort had done in decades:

He freed everyone.

All twenty.

Including Kalenda.

Neighbors called him mad.

Charleston newspapers mocked him.

Politicians warned he was inviting insurrection.

But Hale had learned something:

It was not fear that kept the South together.

It was forgetting.

And Kalenda had taken forgetting away.

Freedom struck Kalenda not as joy but as silence.

A silence too wide to cross in one step.

For fifty-seven years he had lived inside a system built on theft— the theft of breath, of names, of futures. The open world felt unfamiliar, a sky with too many possibilities.

He walked to Beaufort town on unchained feet.

He introduced himself not as Jim, not as Jacob, not as the names he’d been branded with.

“I am Kalenda Adisa,” he said.

And the name felt like a drumbeat resurrected.

He found work teaching the children of freed families. Many did not know where they came from. Their parents had been sold and scattered. Their grandparents’ stories had been burnt with plantation ledgers.

So Kalenda taught them how to rebuild the past from what survived.

He taught literacy.

He taught remembering circles.

He taught witnessing.

And the children—wide-eyed, open-hearted— learned the stories of hundreds whose names had nearly vanished.

He became a walking library.

A living archive.

A flame passed hand to hand.

From 1846 to 1864, he taught more than two hundred people across the Lowcountry. Many of them would later testify during Reconstruction about slave conditions with a clarity northern officials could barely believe.

But Kalenda never sought fame.

He sought closure.

He sought to finish what Sorie Bala had begun in the hold of a slave ship.

And during all these years, he waited for one thing:

The moment he would be allowed to rest.

It came in the spring of 1864.

His breath grew shallow.

His bones tightened.

The world began dimming at the edges, not with fear, but with fullness—like a story nearing its last line.

On the fifteenth of March, rain tapped the roof of his small Beaufort cabin like ancestral fingers.

Around him gathered dozens of the people he had taught.

He whispered one sentence before his final breath:

“Do not bury me. Carry me.”

And they did.

They carried him in memory, which was the only place he ever wanted to live.

Kalenda’s funeral defied the laws of the state.

Nearly three hundred people gathered.

A wave of black faces, freed and enslaved alike, filling the clearing with a presence so undeniable that the sheriff, watching from horseback, decided prosecution could wait for another lifetime.

One by one, they stood.

A young woman recited the lineage of twelve families whose history would have disappeared without Kalenda’s teaching.

A man named Isaac read from a document he’d written—listing punishments, dates, overseers, crimes passed off as routine.

Another sang a griot song nearly lost to time—the melody carried from Senya across the ocean, across generations, across graves.

Every voice was a rebellion.

Every memory a blade.

They turned their grief into testimony.

They turned their survival into scripture.

They turned Kalenda into a legend the law could not contain.

And this is why the South tried to erase him.

Not because he fought with fists.

But because he built witnesses.

Because he proved that the enslaved had not lived in darkness but in watchfulness.

Because he taught that history kept inside a person cannot be burned.

And because he revealed the truth slaveholders feared more than revolt:

that the oppressed were always remembering, even when no one was listening.

The Final Movement

In the years after Kalenda’s burial, the Lowcountry changed color.

Not of skin—of memory.

The people he had taught scattered across South Carolina, Georgia, and the Sea Islands. Some sought wages in towns. Some worked on farms run cooperatively by freed families. Some snuck north. Some joined the Union Army when the war reached their shores.

But all of them carried Kalenda.

They spoke to their children the way he had spoken to them—slow, deliberate, rhythmic, weaving truth into stories like thread into cloth. They told of mothers stolen, fathers broken, voyages survived against the jaws of the sea. They taught the names of those who had vanished, repeating them during storms so the wind could not take them.

And through this retelling, a quiet revolution began.

A revolution with no guns.

No generals.

No flags.

A revolution of remembrance.

When the Civil War ended, federal agents arrived to collect testimony about slavery. The Freedmen’s Bureau tried to document atrocities, map abuse, identify perpetrators. But most freedmen hesitated; speaking truth under oath meant risking retaliation, losing work, or inviting the wrath of neighbors who still believed the old order sacred.

But then came the ones Kalenda had taught.

They walked into those makeshift offices with steady steps.

A woman named Dinah recited exact dates of whippings from twenty years prior.

A man named Ellis described slave auctions in Savannah with such detail the examiner cried.

Two sisters listed every child stolen from the coastal plantations—names, ages, buyers—=” so precise it contradicted official ledgers.

One agent wrote:

It is as if these people hold an archive in their minds, clearer than any courthouse record.

He did not know he was speaking of Kalenda.

Meanwhile, the South tried to forget faster than memory could pursue it.

Plantation owners rewrote diaries.

Churches preached a softened past.

Politicians claimed slavery had been “misunderstood,” “mild,” “beneficial.”

But each time forgetting grew bold, someone would stand and say:

“I remember.”

And the lie would wither.

In 1872, during a legal dispute over land once owned by Edmund Hale, workmen discovered a sealed cavity in the wall of the old plantation house.

Inside were Hale’s letters.

Dozens of them.

Unsent.

Unread.

His handwriting trembled between fear and awakening, describing dreams of bondage, guilt blooming into hallucination, and a man named Kalenda who forced him to see the truth he’d spent his life avoiding.

The letters were submitted to the county archive.

The archivist, a former Confederate officer, read them with rising horror. He wrote across the file:

These documents are dangerous. They must not be circulated.

But ink cannot silence experience, and memory does not consult permission.

The letters leaked anyway—copied by freedmen, read in secret, whispered at night over firelight. They became part of the oral chain, another bead on a story-string stretching from Senya to the Carolinas.

But this circulation did something no one expected:

It awakened Edmund Hale himself.

After emancipation, Hale tried to rebuild his life quietly in Beaufort. He planted gardens. He avoided neighbors. He attended church but spoke little. Some called him broken; others said humbled. Most ignored him, for Reconstruction was a storm swallowing larger men than him.

But when news of his old letters reached him, he did not deny them.

He walked to the county clerk and asked to see the originals.

They trembled in his hands.

His wife watched him from a distance, afraid to approach the man he had become.

“Did he put this inside you?” she whispered.

Hale shook his head.

“No. I hid this inside myself. He only made me look.”

And in that moment, free of whips and laws and the machinery of slavery, Edmund Hale did something extraordinary in its rarity:

He told the whole truth.

Publicly.

Completely.

Without excuse.

He testified before a Reconstruction panel in Charleston, describing not only his plantation but the system itself—the cruelty, the fear, the generational rot. He admitted greed, cowardice, the willingness to blind oneself to preserve comfort.

White citizens cursed him.

Black citizens watched with cautious astonishment.

His own family disowned him.

But Hale felt lighter with every word.

And when he concluded, he said something that would echo in the records for decades:

“I am not the victim of that man. I am the evidence of him.”

He did not live long after that testimony.

But for once, he died unafraid.

Because truth had finally carried him home.

By the turn of the century, Kalenda’s students were elders.

Their hair silvered.

Their voices deepened.

Their memories sharpened by years of retelling.

They taught grandchildren how to rebuild family trees lost to the auction block. They created “remembering circles” every harvest season—gatherings where the youngest listened while the oldest recited histories with the cadence of griots reborn on foreign soil.

And though none of these elders had ever seen Africa, they spoke of Senya as if its dust still clung to their ankles.

As if Kalenda had opened a doorway in their minds and told them:

“Here. This is where your roots begin.”

Some said he performed miracles.

Others said he possessed a mystic gift.

But those who knew him best said nothing supernatural was needed.

Because memory—true memory—was miracle enough.

In 1921, a scholar from Howard University traveled through the Sea Islands collecting oral histories. He found something he had not expected: stories that aligned across families who had not lived on the same plantation for generations.

Stories with the same core.

The same patterns.

The same name spoken like a quiet drumbeat:

Kalenda Adisa.

The scholar wrote in his notebook:

I expected fragments. I found a cathedral.

He followed the stories to Beaufort, where he met a woman nearly a hundred years old. Her vision had dimmed. Her hands shook. Her voice rasped.

But when he asked about Kalenda, she sat straighter.

“Child,” she said, “you asking about the one who kept us human?”

She told him her mother had been one of the twelve who witnessed truth in the woods. That Kalenda walked like a man guided by ancestors. That when he spoke, even the broken felt whole enough to stand.

“And how did he die?” the scholar asked gently.

The old woman smiled.

“Die? Son, he ain’t dead. People die when they get buried. He told us not to bury him.”

She tapped her forehead.

“He right here. Same place he put everyone he carried.”

The scholar left with pages of notes.

But he knew he had not captured the full story.

Because stories like Kalenda are not captured.

They are carried.

Time moved onward.

Wars came.

Wars ended.

New migrations stripped the Lowcountry of families who had lived there for centuries.

Fields turned into roads.

Roads turned into suburbs.

Suburbs turned into memories.

And the story of Kalenda Adisa—like so much Black history—was nearly lost in the noise of progress.

Nearly.

But memory has a strange stubbornness.

It seeps.

It waits.

It returns.

It taps walls like a heartbeat until someone listens.

And that is why, nearly a century later, workers tearing down a decaying house discovered a hidden panel.

A hidden cavity.

A hidden letter.

Hale’s letter.

A story that refused to die.

When the letter reached modern historians, debates erupted.

Was it authentic?

Was Hale exaggerating?

Could memory alone break a man’s mind?

Could one enslaved African truly influence so many?

They argued.

They dismissed.

They resisted.

But eventually, they yielded to the evidence.

Because truth does not vanish simply because it is inconvenient.

Truth waits.

A historian from Columbia University, after reviewing all the testimonies tied to Kalenda’s name, wrote in her final report:

We teach about revolts of the body, but rare are histories of revolts of the mind. Kalenda Adisa led neither insurrection nor army, yet he destabilized the ideological foundation of slavery: the belief that the enslaved had no interior life. His rebellion was memory. His weapon was truth. And in this way, he stands among the most consequential freedom fighters of the American continent.

But the most powerful acknowledgment came not from scholars.

It came from descendants.

Hundreds of names once scattered across plantations began appearing in genealogies reconstructed by families who had never before known where they came from. Every branch of every tree traced back to someone who had been taught, directly or indirectly, by Kalenda.

A lineage rebuilt from ash.

A nation inside a man.

And so, when we tell the story today, we do not speak of him as a ghost, or a prophet, or a miracle-worker.

We speak of him as something rarer:

A man who understood that history is not what happens.

History is what survives.

He survived.

His people survived.

His memory survived.

And every time someone whispers the truth of the past, a small piece of Kalenda Adisa steps forward, carrying the weight of those who could not speak for themselves.

He asked for one thing before he died:

“Do not bury me. Carry me.”

And we still do.

Not in tombs.

Not in monuments.

Not in textbooks alone.

But in the oldest library the world has ever known—

the human mind, where flames do not fade,

and stories, once lit, do not die.

This is the forbidden song he left behind.

And now that you have heard it,

you carry him too.

News

End of content

No more pages to load