She worked like a woman born older. She fetched firewood, each log a promise. She mended the roof where the drifter had thrown his weight and left a broken tile. She fed fenland stock that no longer belonged to her and gathered eggs when she could find them. She ate less than she should have and drank bitter coffee until it felt like a thing that kept her upright.

Neighbors watched. Men on larger ranches rode past and tipped their hats though the tips were clumsy. Ranch hands whispered. One or two of the women crossed themselves when she passed. A man named Hale brought a square of bacon and set it on her stoop without looking at her. He had a daughter the same age as Ruby and the look of a man who did not like to be tender. He did not speak much. He came when he had wood and left when there was grain to be split.

People told stories then like they told cold weather: to make sense of danger. The story of the girl who would not leave spread. It became, in the telling, something larger: defiant, admirable, an example. Strangers arrived with tools and lumber and blankets. A boy from the town station—young and round-faced—brought nails and a box of screws. A widow named Eliza brought a bolt of cloth and the knowledge of how to stitch insulation. They did not come because it was worthy. They came because there were reasons in every town that simple acts of kindness are the glue.

When neighbors came it was never a fete. They came in small numbers, at dusk and at dawn. They worked quiet. They did not ask. Ruby watched them from the doorway with her hands folded. She would not let them see how hollow the nights had been, how she had set a chair in the center of the room and talk as if people sat in it. She would not let them see the moments she laid her forehead to the latch of the door and counted breaths.

The drifter drifted. Men like him cannot be held by a roof. By spring he had moved on. He rode out with a swagger and a pack of old bottles. The roof Ruby and her helpers had put over the house was new wood and had a seal against the weather. Snow melted into runnels and pooled by the barn. Mottle clucked and scratched in thawed dirt. The land smelled of its own slow coming back.

The miracle people remember is seldom a moment. It is more often the accumulation of small decisions. Ruby learned to coax a garden from the ground. She planted what she could, saved seed in a jar wrapped in cloth, and watched the green lift. She carved spoons and a small cradle. She mended clothing for the elderly. Her hands always had some small work.

But the winter had left tracks. There were debts—loans taken for coffins, for a fence that had rotted. The county records were not kind to orphans. There is a ledger of law and one of mercy; Ruby had acquaintances who favored the latter. A clerk in Pine Bluff—a man with soft eyes—brought a document one afternoon and said that if she would sign it the county might look after the minor affairs until she came of age. Ruby read the paper and then folded it without fury. She would sign nothing to give away the claim her father had beaten out of sod and rock.

Time, then, became the other wall she faced. People come and go on the plains. Some add; some take. It was the pattern of their lives. Ruby fit into that pattern by being as steady as a post in the ground.

Summer came thin and fierce. Ruby trod a narrow path between grief and persistence. She did not talk about the hollow places in her chest. She kept them like a secret that belonged only to her.

One evening in late summer, when the light was silver and the hay had the smell of sun and old bees, the drifter returned. He arrived not alone this time. He was with two other men and a wagon. They had the look of men who took advantage of endings and had a strategy for fussing out what they called right.

They pulled up and the horses stamped their impatience in the dust. Ruby was at the well; she had a bucket in each hand. The drifter stepped forward and set his palm on the fence rail as if he owned the wood. He squinted at her like a man checking the weather. He smiled and it was a smile that wanted to be mean.

“You still here, little bird?” he said.

Ruby did not move for a heartbeat. Then she set the buckets down with a careful ease and wiped her hands on her skirt. “You left,” she said.

“You ain’t got much here for a man.” He looked past her to the rows of beans and the cluck of Mottle. He looked at the cradle. The man laughed, low and ugly. “Not much, but good enough.”

“You can’t just take,” Ruby said.

“You’re a child,” he said. “You don’t own much. No one who matters’ll care.”

The two men with him snorted. One spat.

Ruby had no lawman with her, and the nearest deputy was some hours away. She had, however, a kitchen of witnesses on the hillside. She also had a stubbornness that did not know how to back down. She went to the yard and lifted the gate. Her hands were small against the weight.

“You’re going to have to show me,” she said.

He pushed. They argued. Men exchanged jokes at the expense of women. The drifter said he had a right to possess the property because he had paid for debts in whiskey and in threats. Ruby said she had a deed tucked in her father’s trunk and that deed had the county seal. The drifter snarled.

“You’ll need more than paper,” he said.

That night the drifter and his men lashed themselves in the barn, but the barn was not theirs to stay in without a lawyer’s instrument. They set about breaking the fence at dawn. Ruby found them with crowbars and a small-headed malice. One of the men swung and the iron struck a post and sent a splinter into the air. The sound was like a small gun.

Ruby stepped between the swing and the post. “Stop,” she said.

He laughed. He thought a girl like her would retreat. His grip hardened on the bar. The sunlight ran white across his arm.

The second man, a broad-shouldered fellow with a whisker that stopped near his mouth, stepped forward. He had a smirk like a coin. “Move,” he said to Ruby.

“You move,” she said. “Get off my land.”

For a long minute the two of them measured each other like two horses at a gate. The drifter moved closer to the man with the crowbar as if to check his loyalty. Ruby watched the set of his shoulders. She could smell the whiskey on his breath even from where she stood.

Something broke the air then. A voice from the road, calm and steady. “That’s enough.”

There was a man on a horse held at the edge of the path. He had the look of a man who carried the law by habit more than by hunger. Sheriff Booth had the soft eyes like the clerk but with the set of one who had been on cold nights many times before. Behind him walked a woman carrying a bundle of blankets. There were others—two men from the Hale place, Eliza with her length of cloth, and a boy from the station.

The drifter spat and set the crowbar down. He had the look of a man who would have pushed it farther only if the law had not stood at his back. “You got no proof,” he said.

The sheriff stepped in, the leather of his gauntlets creaking. He examined the papers Ruby held with small, practiced gestures. He read the seal and looked at Ruby with a patience that was not pitying but practical. He said, “This is in order.”

The drifter’s face narrowed. He went red with the sort of temper that gets worse with whiskey and less with thinking. He said words that were meant to cut—about being a child, about being a fool, about how the world eats those who do not fight—but the sound of them had less weight when the sheriff heard them.

“You’ll leave,” the sheriff said.

The drifter spat on the ground as if the earth were somehow at fault in this. He turned his back and walked off with his men, but he left a feeling like a storm cloud over the day. People drift away thinking that space is a thing you can take and keep; sometimes it answers back.

For a time, the matter was done. The sheriff had a way of closing things without noise when the law tallied the right numbers. The drifter rode away and the men with him muttered curses. The sheriff lingered only a short while to ask Ruby if she had need and to promise a watch now and then. He did not promise the impossible. He promised the small favors of a man who knew frost.

In the weeks that followed, the work of living resumed its ordinary, sacrificial rhythm. Ruby kept the garden, fixed the fence, and mended the roof where the storm had bent a tile. She taught herself to stitch a seam so tight it would not let the rain find its way. She learned to bargain for grain and to bargain more for mercy. When a boy from Pine Bluff came to trade for eggs, she bartered a spoon she had carved and left with a sack of flour that had a smell like the sweet of hope.

There were small triumphs: a hen that had been too thin grew plump and hearty; a neighbor taught her how to graft a pear tree. There were losses too: a sow died of fever they could not diagnose in time, and Ruby felt that the world had grown narrower for each opening.

People continued to talk about the girl who would not leave. But talk is a poor currency for the work of life. The real ledger was written in hands and in sweat.

Then, one autumn, things snapped.

There was a night when the wind came like the mouth of a beast and thought to make a ruin of everything it touched. The rain turned to sleet and hammered the windows. Ruby woke to the sound of nails giving. She thought at first it was a branch, then the cry came: fire.

It began at the far side of the barn. A light like an ember flicked through the planks and then grew. The barn had been patched, but old wood takes fire with the ease of a memory catching. Ruby leapt from bed with a shawl low over her shoulders. The house was small; she could feel everything at once: heat on her face, the sputter of wet as snow melted and steam rose. Mottle clucked in panic and ran, feathers in a blur.

She ran for Buck—the neighbor’s boy—who had been staying the night. He was awake and he moved like a boy taught to work. He grabbed a bucket. Hale came with a team of men and the sheriff with his coat flapping.

They pulled water from the creek. They hauled at the barn with axes until the roof came down with a sound like a collapsing heart. Someone threw a blanket on the embers. Smoke stung their eyes. When the last flare died, men stood and panted like dogs. The barn had mostly burned, though the house held and the roof had been saved by a quick thinking.

It was then the drifter came back.

He had been watching at a distance, they said—calling no man his friend and hunting possibilities. He claimed not to have started the fire and said that he had tried to help. The sheriff’s eyes narrowed at that. No one believed him. The embers were cold evidence and could not tell tales, but a man’s movements can. He had been seen with a lantern near the outbuildings earlier in the day. Men had noted it and stored the thought away like rocks in a pocket.

That night they brought him to the edge of the town. There were men with grudges. They wanted the swift and final justice of frontier stories. They wanted blood for a barn. They wanted to burn a man in public because a man’s sins are the easiest to show when wood is in the yard.

Ruby could have stood with them. She had every reason: loss and insult and the grazing of the drifter’s hands on her life like a scab. It would have been easy to let rage carry her forward. But she had something else: a stubbornness that had no desire for scarifications it did not need. She had a memory of the time her father had said small things about fairness, long after the notion had seemed ridiculous: “Justice is not a thing we make by our anger,” he had said once, and then spat tobacco into the dirt. Ruby clung to that sentence like a plank when the wind came.

She stood then on the edge of the circle of light where men gathered and said, “No.”

“Let the sheriff do right,” she said. “If he did it, he should pay like one who did; if he didn’t, then—”

“If he didn’t he gets a trial,” the sheriff said. He had the sense not to smile. He had a way sometimes of being blunt that reminded one of farming: you set the seed and then you wait and tend it. “He’s under arrest.” He cuffed the drifter with a cool hand. “He’ll be held till morning and sent to Pine Bluff to answer.”

The men around them spat into their palms and muttered. They had wanted more immediate theater. But the sheriff was a thing of slow craft, a man who knew the difference between vengeance and law. The drifter was taken. He swore and swore and used words like a man who thinks a tall hat makes him respectable.

Morning brought a courtroom in Pine Bluff that smelled of boiled coffee and old wood. Witnesses shivered under the scrutiny of a bench that had been made for small, stern things. The drifter lay and denied and offered new versions of truth like a man altering a coat to fit. He spoke of being framed and of people who had it in for him. Men who had earlier whispered against him tensed as their names were offered up.

The sheriff and the clerk and a man from the Hale place testified to the lantern on the ridge and the men sawed by the memory. Ruby sat in the front row with Mottle in a small basket at her feet. She had wrapped the hen in a scrap of wool. She kept her chin down. There were questions asked of her about a door being closed and being forced. She answered plainly, in the way patents are made: fact, not embellishment. The law hung on facts like fruit on a tree.

The drifter’s face turned a color when the clerk produced a statement—an old ledger entry signed with the drunk’s name, where he had boasted in ink of a plan to take the cabin. His words betrayed him as if their ink could not be whitewashed. The judge spoke slow and with the gravity of one who had been to hard winters himself. He said a man who steals land and sets fire to the structure where children or helpless folk stay does not receive light treatment. He sentenced the drifter to a stretch in the county lock and ordered restitution to be made where it could.

The drifter struck his fists and cursed. He wanted to be writ small and done with. He wanted the roar of vengeance that men like him count upon. But the sheriff’s law, which was not always kind, was finally the firmest thing in that room that day.

When the drifter was taken away, it felt like a thread snapping. It was not perfect. It rarely is. The barn could not be replaced with a sentence. But the law’s strand pulled him from the edges of Ruby’s life.

After that, time settled a way of its own. Seasons have the cruel decency of recurrence. Spring came with the usual hardness followed by the green spikes. Ruby planted again. She put up posts. Men and women from the town came with hands that were quiet and steady. They brought saplings and taught her the method of graft. Hale’s daughter used fingers that knew how to sew and shared stories of a life she would have. Ruby listened and sometimes allowed herself to laugh. Laughter in such places sounds like something stolen but returned.

There were hard days—times when a sickness would move through the livestock, or when crops failed because of drought. But a community, even a sparse one, is like a net; when one of them fell, others tightened around.

Ruby grew in the way that land grows a crop: slowly, patiently, and with an eye to the long. She learned to read the sky in ways she had not as a child. She argued with merchants in Pine Bluff and won a discount on a sack of oats. She sat at night and drew plans for a new lean-to and kept notes in a small ledger in her father’s hand.

The chicken, Mottle, became something more than a source of eggs. It became a marker. Children in the town would come and sit on the stoop and watch Ruby braid wire for a fence. They asked her for stories about her parents and she told them in small pieces the things that did not break the telling. She made them bowls of cornmeal when their mothers were sick. In time a boy named Samuel—who had been neighbor’s child—fell in love with the way she tamped the soil and the courage in her hands.

Ruby did not forget the winter she had nearly frozen in. She did not forget the smell of whiskey on a man’s breath, the sound of a door slammed, or the small weight of a chicken pressed to her chest. She kept those like a map. They told her where the cliffs were and where the safe channels lay. She would tell them when the moment came and some would learn and some would not. People do not always choose the lessons; sometimes they are passed on like heirlooms.

Years passed. The claim that had been Ruby’s alone slowly became more: a barn rebuilt with sturdier logs, a small orchard that began to hold fruit, a fence that ran longer than it had when her father paced it. They put a porch on the house and a new window where the old one had been marked by a hand. Children came to play beneath the eaves. There were births and small funerals; the circularity of the place held on.

The drifter—he came up in talk like an old bruise. Men who had known him nodded in the street and changed their steps when his name came up. He was, in time, a cautionary illustration in a hundred stories told to boys with wild inclinations. It is strange how time can make monsters small.

One summer, decades after that winter that was almost the end of her, Ruby sat on the porch with a bowl of sliced peaches and listened to the hum of bees. She was older, the lines near her eyes carved by wind and work. Hale’s daughter had married and had a string of children who liked to run across Ruby’s yard—they called her Aunt Ruby though there was no blood. Samuel had left and returned with a steady patience to help keep the property. He had a hand that fit around the small of her back like a second body.

Mottle had long since gone to where hens go. There was a small coop now with more than one hen. The birds scratched at the ground with a busy dignity. Ruby kept them because she had learned that life could be coaxed back.

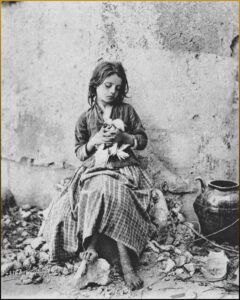

A young girl came, though, to the gate one morning. She was the same age Ruby had been at the worst. Her cheeks had the pallor of someone who had slept outside. She clutched a bundle—a small dog maybe or a hen, it was hard to tell. She walked up the path and looked at Ruby with an open asking.

Ruby could have been stern. She could have closed the door. She had every reason to be selfish with the small things. The girl opened her mouth and said, “My name’s Elsie. I have nowhere else. Please.”

Ruby looked at her the way a skilled person will in order to understand the weight in someone’s hands. She saw her own thin fingers, the tired set of someone who had not been offered warmth. She saw the way her jaw was set like a plank.

She let the girl in. She wrapped a blanket around the small bundle of bird and set a cup of coffee in front of her. She told her, quietly, the things that measure a life: how to stack wood so rain does not rot it; how to bind a wound; how to be patient with the earth.

The girl learned and, in the learning, brightened. She stayed. She planted and tended. She grew a stubbornness that was not different from Ruby’s but was her own. The old woman watched with a satisfaction like a farmer at harvest.

In the winter evenings, when snow came and the light from the window painted a rectangle on the porch, Ruby would sometimes take out her father’s small ledger and thumb it. She would read the names scratched there and feel something like company. She would set the book down and listen to the night. She kept her hand on Samuel’s for the comfort of knowing they were still there.

One day, when Ruby was very old, and her hair had the silver of the high plains frost, she took Elsie to the edge of the field where a small plaque was set in a stone. It had been put there by hands that wanted to keep the story true. It read nothing fancy: LOGAN & MARY CARTER. HOME.

“You remember,” Ruby said.

“I do,” Elsie said. She bent and brushed the stone with her knuckles like someone petting a small animal. She looked up at Ruby. “Why’d you stay?”

Ruby’s face was a map of a life now well-worn. She thought a small while, as if choosing how to tell the truth. “There was nothing for me if I left,” she said. “But that isn’t the only reason. I stayed because it was where they were. I stayed because leaving would have been like forgetting them. I stayed because sometimes a place needs someone to hold it steady so other folk can come to live there.”

“And Mottle?” Elsie asked.

Ruby smiled, the smallest smile. “Mottle kept me warm through the worst nights. She reminded me that little things matter. She reminded me to feed the things that feed me.”

The girl laughed like something that had been taught to be brave. “I’ll keep the place,” she said.

Ruby set her hand on the girl’s head, which was still a small warm thing. “Do,” she said. “Keep it to the best of your ability.”

There is a kind of justice in small steadiness. Not thunderous, not baked into legends men shout across rooms, but the justice that comes when a person refuses to be moved by the easier paths. Ruby had been stubborn. She had been precise. She had been tenacious in a way that required no one’s applause. She had not sought to be hero. She had chosen the daily labor and continued.

At the end, she did not have wealth. She had a house that held memories and a field that fed. She had friends and a girl who would keep the place. She had a bench on the porch where she could sit and listen to the sound of the world moving—quietly, inevitably.

When she died the neighbors came with a stoic tenderness. They closed her eyes and set floral cloth over her chest. The land hummed with the ordinary sound of living. Samuel pressed his hat to his heart. Elsie read the short ledger of names and said a small, clear thing. “She stayed,” she said. “She kept the place.”

They buried Ruby under the stone with her parents. The marker read her name and the dates of her life. Children placed small pebbles at the foot. A hen wandered through the graveyard, unconcerned by sorrow. The sun was bright. It was the kind of day that seemed to insist on the world continuing.

The house stood. The orchard bore fruit. The porch chair held the imprint of a body that had done its work. In time, that imprint faded but the stories did not. The town told of the girl who would not leave and of how she had kept a piece of land open in a place where fortunes moved like wind. They told how, against the easier pull of retreat, she had stayed.

Ruby’s life was not a sermon or a legend. It was the series of small obligations met again and again. It was the grit of someone who did not expect to be saved and who did not expect reward beyond a good meal and a warm bed. Yet in the way she lived, she gave something else: an example, plain and stubborn, that other folk might see and, perhaps, mimic.

If you stand now at the edge of the Carter claim where the wind hits the porch just so, you can see the white of the stone. If you listen you might hear, not the grand music, but the small sounds of life—the cluck of hens, the whisper of trees, the creak of a chair in the evening. It is not a loud history. It is the quiet kind that lasts.

News

On 30 January 1934 at Portz, Romania Eva Mozes and her identical twin sister Miriam were born on 30 January 1934 in the small village of Portz, Romania, into a Jewish farming family whose life was modest, close-knit, and ordinary.

Relocate. The word floated into Eva’s ears as if wrapped in wool, muting its severity. She was ten. How could…

He was no more than ten years old when the streets of Victorian London became his only home. No name anyone cared to remember, no family waiting, no warm bed calling him back.

He had one treasure: a small, slim book with a maroon cover, its pages begun but never finished. He found…

Gillian was only seven years old when the world decided there was something fundamentally wrong with her.

The people behind the glass moved and leaned. The mother’s face softened until she looked very young, like someone remembering…

“Come With Me… The man Said — After Seeing the Woman and Her Kids Alone in the Blizzard”

Marcus kept his voice low; low voices never sounded like danger. “My place is ten minutes from here,” he said….

single dad accidentally saw his boss topless at the beach and she caught him staring

What the note did not prepare me for was the way looking at Victoria would become a private weather system…

(1856, Sara Sutton) The Black girl who came back from the de@d — AN IMPOSSIBLE, INEXPLICABLE SECRET

Sarah rose like a thing that had been to the edge and found a way back. Mud clung to her…

End of content

No more pages to load