That night, back in her small apartment, she wrote the question again at the top of a fresh page: Were there ever any women scientists?

She did not write an answer. Instead, she wrote: How would we know?

Margaret had been trained to respect archives. She believed in documents, in paper trails, in footnotes that could be followed like breadcrumbs through time. If women had not been scientists, the record would show it. If they had been, the record would show that too.

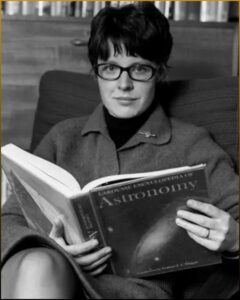

She began where historians always begin: reference books.

One afternoon in the Yale library, she pulled down a thick volume titled American Men of Science. The title alone seemed to settle the matter. But habit, not hope, made her open it anyway.

She flipped through the pages, expecting a parade of Johns, Williams, and Roberts. Instead, she froze.

There, in neat alphabetical order, were women.

Botanists trained at Wellesley. Geologists from Vermont. Chemists, physicists, biologists. Each entry was formal, restrained, factual. Education. Institutional affiliation. Research interests.

They were not footnotes. They were not anomalies. They were professionals.

Margaret sat back in her chair, the book heavy on her lap. The professors at the pub had been wrong. Not vaguely wrong, not philosophically wrong. Factually wrong.

This discovery thrilled her for about ten minutes.

Then the unease returned, sharper now. If these women existed, why did no one talk about them? Why were they absent from lectures, from syllabi, from the easy certainty of Friday afternoon conversations?

She began to look deeper.

Margaret requested access to university archives, museum collections, private papers. She traveled when she could, writing careful letters asking for permission to examine boxes that had not been opened in years. She learned the language of archivists, the etiquette of gloves and pencils and patience.

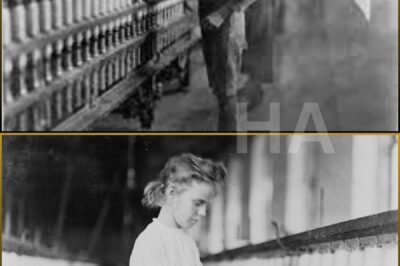

In one archive, she opened a folder of laboratory photographs from the late 1800s. The images were sepia-toned, slightly faded. Men in dark suits stood stiffly beside benches cluttered with glassware and wires. And there, among them, were women.

They were not decorative. They were not on the edges of the frame. They were leaning over microscopes, adjusting equipment, holding notebooks. Their faces were serious, focused, unposed.

Margaret felt a quiet exhilaration. Here they were. Proof not just of presence, but of participation.

She copied names from the backs of photographs. She followed trails to published papers, award announcements, institutional histories.

And then something unsettling emerged.

The women in the photographs were missing from the texts.

The published papers listed male authors only. Award citations praised “his” insight, “his” leadership. Institutional histories mentioned assistants, sometimes anonymously, sometimes not at all.

Margaret checked again, convinced she had made a mistake. She compared dates, projects, equipment. The match was unmistakable.

The women had been there. Then they had vanished.

At first, she considered the possibility of coincidence. Perhaps a few cases had slipped through the cracks. But as she moved from archive to archive, the pattern repeated itself with chilling consistency.

A woman designed an experiment. Her supervisor published the results under his own name.

A woman made a crucial discovery. Credit was assigned to the lab director.

A woman co-authored a paper. Her name appeared only in the acknowledgments.

A woman’s work formed the backbone of a research program. The awards went elsewhere.

This was not random. It was systematic.

Margaret began to feel like a witness at a crime scene that spanned centuries. The evidence was everywhere, once she knew how to see it. But the crime itself had been normalized, folded into institutional habits so thoroughly that no one thought to question it.

She filled notebooks with case after case. She copied letters in which women expressed frustration, gratitude for crumbs of recognition, resignation. She read correspondence between male scientists that treated women colleagues as interchangeable labor, as extensions of equipment.

At night, she lay awake, her mind buzzing. This was not just about correcting a few footnotes. This was about the architecture of scientific credit itself. About who was seen as capable of genius, and who was assumed to be merely helpful.

Margaret realized she needed language. Without a name, the pattern remained slippery, easy to dismiss as anecdotal or emotional. Historians respected frameworks. Terms. Concepts that could be tested, debated, refined.

For years, she worked without one.

She completed her dissertation and continued her research, moving through academic positions, often encountering skepticism. Women’s history, some colleagues suggested, was advocacy, not scholarship. Others accused her of reading modern politics into the past.

Margaret responded the only way she knew how. She did not argue about intentions. She argued with evidence.

She laid out cases side by side. She demonstrated repetition. She showed how the same mechanisms appeared across disciplines, institutions, and eras.

Still, something was missing.

In the early 1990s, while reading the work of nineteenth-century feminists, Margaret came across an essay by Matilda Joslyn Gage, a suffragist writing in 1870. Gage had described how women’s inventions and discoveries were routinely attributed to men, how female creativity was systematically minimized or erased.

Margaret felt a jolt of recognition. The phenomenon she had been tracing had already been named, at least in spirit, more than a century earlier.

In 1993, she published a paper that formally named it: The Matilda Effect.

The term was elegant, pointed, and quietly devastating. It framed the erasure not as a series of unfortunate accidents, but as a recognizable pattern of bias. Once the name existed, scholars could not unsee it.

Margaret’s work gained momentum.

She embarked on what would become her life’s project: a comprehensive, three-volume history titled Women Scientists in America. It was not a polemic. It was an excavation.

She examined institutional policies that barred women from faculty positions. She traced hiring practices that confined women to temporary roles. She analyzed citation patterns, authorship conventions, prize committees.

She wrote about individual careers with care and precision, restoring context where myth had flattened complexity.

Rosalind Franklin emerged not as a footnote to DNA’s discovery, but as a rigorous crystallographer whose X-ray diffraction images were foundational. Lise Meitner appeared not as a forgotten collaborator, but as the scientist who explained nuclear fission while her male colleague received the Nobel Prize. Nettie Stevens, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, and countless others stepped back into view, their contributions clear once the fog of bias was acknowledged.

Resistance did not disappear. Some critics accused Margaret of exaggeration. Others suggested that standards had simply been different in the past, that exclusion was unfortunate but inevitable.

Margaret did not raise her voice. She did not accuse individuals of malice. She showed structures. She showed outcomes.

Slowly, the ground shifted.

The Matilda Effect entered academic vocabulary. Graduate students used it to analyze authorship disputes. Committees cited it when revising award criteria. Universities reconsidered how they taught the history of science.

Curricula changed. Biographies were rewritten. Entire fields began to re-examine their foundational narratives.

Margaret received recognition, though she rarely spoke of it. The Sarton Medal, the highest honor in the history of science. A MacArthur “genius” grant. A department created in part to keep her at Cornell.

But the recognition she cared about most was quieter. It was the moment when a student said, “I didn’t know she existed.” When a name, once erased, returned to circulation.

Margaret was careful never to suggest that bias belonged only to the past. In lectures, she pointed to contemporary =”. Women scientists still received fewer citations. Fewer major awards. Fewer promotions. The pattern persisted, even as its forms evolved.

But now it had a name.

And once a pattern is named, it can be measured. Once it can be measured, it can be challenged.

In her later years, Margaret often returned to those early laboratory photographs. She thought of the women who stood at benches in stiff dresses, their hands steady, their faces serious. She imagined them watching from across time as their names resurfaced, tentative at first, then firmer.

On August 3, 2025, Margaret Rossiter died at the age of 81.

News of her passing moved through academic circles with a particular kind of gravity. Obituaries described her as meticulous, rigorous, transformative. Students and scholars shared stories of how her work had changed their understanding of science, of history, of fairness.

But beyond the accolades, her true legacy was less tangible and more enduring.

Because of her, the absence of women in scientific narratives could no longer be taken at face value. Because of her, silence itself became a clue. Because of her, generations learned to ask not only who was celebrated, but who was missing.

Margaret had begun with a simple question, asked carefully over a beer in a crowded pub. She had followed it into archives and arguments and decades of patient work.

She had shown that history is not just what happened. It is what we choose to notice, record, and remember.

And she had proven that when even one historian refuses to accept a convenient story, the past can change shape, releasing voices that had been waiting, quietly, to be heard.

News

In 1991, a 21-year-old posted “just a hobby, won’t be big” to an internet forum. Today, his “hobby” runs 96% of the world’s servers and 3 billion phones. You’ve used it today—and never knew.

He started with small goals. Make the computer talk to him properly. Make it handle tasks the way he wanted….

He called his wife ‘the most beautiful animal I own’ on live TV. She stood up, said ‘I have to leave,’ and walked off—while millions watched. That was 1972, and we’re still talking about it.

A small ripple of laughter moved through the audience. Not because it was funny, but because that was what audiences…

She discovered that breast milk changes its formula based on whether the baby is a boy or girl. Then she found something even more shocking: the baby’s spit tells the mother’s body what medicine to make.

For decades, science had treated breast milk like gasoline. A delivery system for calories, fat, protein. Simple fuel for a…

The bill said $0. She thought it was a mistake. Then she realized someone had finally seen her as human.

The Bill That Said Zero The bill said $0. For a long second, the woman at table seven thought the…

He stole her invention and told the judge no woman could design something so complex. She walked into court with 4 years of evidence—and destroyed him.

While other girls asked for dolls or ribbons, Margaret wanted a jackknife. A gimlet. Bits of scrap wood. She liked…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S SHOCKING ESCALATION: A Single Impeachment Move in Washington Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm No One Saw Coming

A Single Impeachment Move Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm in Washington Updated with today’s escalation, the showdown over HHS Secretary Robert…

End of content

No more pages to load