For decades, science had treated breast milk like gasoline. A delivery system for calories, fat, protein. Simple fuel for a growing body. When researchers talked about milk, they talked about how much energy it provided, how fast it helped babies gain weight.

But if milk was just nutrition, why would it be different for sons versus daughters?

Evolution was rarely wasteful. Producing milk cost mothers enormous energy. Every calorie diverted to milk was a calorie not used for survival or future reproduction. There was no reason for milk to differ by sex unless those differences mattered.

Katie kept digging.

She expanded her =”set. She analyzed over 250 mothers across more than 700 sampling events. The work was slow and meticulous, the kind of science that required patience bordering on obsession. She spent long days pipetting tiny volumes of milk, labeling tubes, logging =”. She spent long nights running analyses, learning to see patterns others missed.

With each new analysis, the picture grew clearer and more astonishing.

Young, first-time mothers produced milk with fewer calories but dramatically higher levels of cortisol, a stress hormone.

That alone was interesting. But when Katie looked at the babies who drank that milk, her breath caught.

Those infants grew faster. But they were also more nervous. More vigilant. Less confident.

They startled more easily. They clung more tightly to their mothers. They explored less.

The milk wasn’t just feeding the baby’s body.

It was programming the baby’s temperament.

Katie felt a chill crawl up her spine. This wasn’t just biology. This was behavior. This was personality. This was the shaping of a life trajectory through a liquid medium no one had taken seriously enough.

Milk was telling babies something about the world they had been born into.

If your mother was young and stressed, the milk carried that signal. Grow fast. Stay alert. Be cautious. The world might not be safe.

It was adaptive. It was elegant. And it was completely invisible to the way science had been thinking.

Still, the most astonishing discovery was yet to come.

It began, as many scientific breakthroughs do, with an anomaly. Katie noticed that immune markers in milk changed rapidly when infants were sick. Not over weeks. Not even over days.

Over hours.

At first, she assumed there must be a delay she wasn’t seeing. Maybe the timing of sample collection was off. Maybe the mothers were responding to environmental cues or behavioral changes.

But the changes were too fast. Too precise.

Then she stumbled across a little-known physiological mechanism that made her stop cold.

When a baby nurses, tiny amounts of saliva travel backward through the nipple into the mother’s breast tissue.

It sounded counterintuitive, almost wrong. But anatomically, it made sense. The nipple wasn’t a one-way valve. During suckling, negative pressure and microflows allowed saliva to enter the milk ducts.

That saliva wasn’t just spit.

It contained information.

It carried bacteria, viruses, and immune signals from the baby’s mouth. It was a biochemical status report.

If the baby was fighting an infection, the mother’s body detected it.

And then, like a living laboratory, her immune system went to work.

Within hours, the composition of the milk changed.

White blood cell counts jumped from around 2,000 per milliliter to over 5,000.

Macrophage counts, the cells that engulf and destroy pathogens, quadrupled.

Specific antibodies tailored to the baby’s infection began appearing in the milk.

Then, once the baby recovered, everything returned to baseline.

No waste. No excess. No lingering inflammation.

It was a conversation.

A biological dialogue between two bodies.

The baby’s spit told the mother what was wrong. The mother’s body responded with exactly the medicine needed.

Katie stared at the =” late one night, her lab notebook open beside her, hands trembling slightly.

This was ancient.

This was older than language, older than writing, older than medicine. This was a communication system that had been evolving for hundreds of millions of years, refined by natural selection long before humans ever existed.

And science had barely noticed.

She imagined the countless mothers throughout history, sitting in huts, caves, villages, apartments, nursing sick babies without understanding the molecular ballet unfolding between them. No doctors. No prescriptions. Just a quiet exchange of information and response.

Invisible. Precise. Powerful.

A language hidden in plain sight.

When Katie tried to explain this to colleagues outside her immediate field, the reactions were mixed. Some were fascinated. Others were skeptical. A few were openly uncomfortable.

One senior researcher laughed and said, “You’re telling me milk is smarter than we are?”

Katie smiled thinly. “In some ways, yes.”

The deeper she went, the more disturbing the broader picture became.

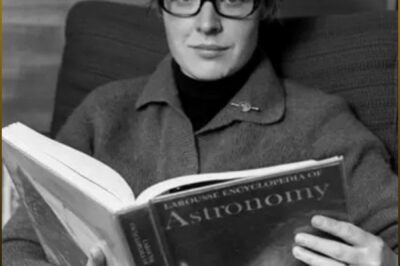

In 2011, when Katie joined Harvard, she began digging into the existing scientific literature on lactation. She assumed she was stepping into a vast, well-developed field.

What she found instead made her angry.

There were twice as many scientific studies on erectile dysfunction as on breast milk composition.

Twice as many.

The world’s first food, the substance that had nourished every human who ever lived, was scientifically neglected.

Funding agencies dismissed it as “women’s issues.” Journals relegated it to niche sections. Medical training barely covered it beyond basic nutrition.

Katie felt a familiar burn behind her eyes. This wasn’t just an oversight. It was a pattern. The same pattern that had dismissed her early findings as noise. The same pattern that treated female biology as secondary, messy, unimportant.

So she did something unusual for an academic.

She started a blog.

She gave it a deliberately provocative title: “Mammals Suck… Milk!”

It was part joke, part challenge. The kind of title that made people laugh and then think twice.

She wrote about milk as a dynamic system, not a static substance. She wrote about hormones, immune cells, evolutionary strategies. She wrote in plain language, refusing to hide behind jargon.

She didn’t expect much.

Within a year, the blog had over a million views.

Emails poured in. Parents. Lactation consultants. Pediatricians. NICU nurses. Fellow scientists. People asking questions research had ignored for decades.

“Why does my baby nurse more at night?”

“Why does my milk look different in the morning?”

“Why does breastfeeding feel different with each child?”

Katie answered as many as she could. She listened. She learned.

And the discoveries kept coming.

Milk changed throughout the day. Fat content peaked in the mid-morning, not at night as many had assumed.

Foremilk differed from hindmilk. Babies who nursed longer received higher-fat milk toward the end of a feeding, a built-in incentive to keep nursing.

Human milk contained over 200 types of oligosaccharides. Complex sugars that babies couldn’t even digest.

They existed solely to feed beneficial gut bacteria.

Milk wasn’t feeding the baby directly. It was feeding the ecosystem inside the baby.

Every mother’s milk was unique. Not just by culture or diet, but by genetics, health status, stress levels, even time since birth. Milk was as individual as a fingerprint.

The more Katie learned, the more she realized how deeply wrong the “milk as fuel” model was.

Milk was software.

It was code, written in molecules, updating in real time.

In 2017, Katie stepped onto the TED stage. The lights were blinding. The audience a dark sea of faces. She took a breath and began telling a story that started with monkeys and ended with humans.

She talked about sons and daughters. About cortisol and temperament. About spit traveling backward through nipples.

The audience leaned in.

Millions of people watched that talk online. Comments flooded in. Some were stunned. Some were skeptical. Many were grateful.

For the first time, countless parents felt that their lived experiences had a scientific explanation.

In 2020, Katie appeared in Netflix’s documentary series “Babies.” Cameras followed her into the lab. She explained her work to a global audience, her enthusiasm infectious, her wonder genuine.

Viewers watched her describe milk as a living tissue, an extension of the mother’s immune and endocrine systems. They watched animations of antibodies flowing into milk ducts, of hormones shaping infant brains.

For many, it was the first time they had seen breastfeeding portrayed not as sentimental or moral, but as profoundly biological and intelligent.

Today, at Arizona State University’s Comparative Lactation Lab, Dr. Katie Hinde continues her work.

Her lab hums with activity. Graduate students pipette samples. Freezers store milk from humans, monkeys, seals, and other mammals. Whiteboards fill with equations and diagrams.

The implications of her research ripple outward.

In neonatal intensive care units, her findings inform care for fragile infants. Preterm babies, whose immune systems are underdeveloped, benefit enormously from tailored milk. Understanding how milk changes helps clinicians support mothers more effectively.

For mothers who can’t breastfeed, her work helps improve formula. Not by trying to copy milk exactly, which may be impossible, but by understanding what functions milk serves and how to approximate them.

Public health policy shifts slowly, but it shifts. Milk banks reconsider pasteurization protocols. Hospitals rethink feeding schedules. Researchers begin asking better questions.

And beneath all of it lies a deeper philosophical shift.

Milk has been evolving for 200 million years. Long before humans. Long before dinosaurs. Long before flowers or birds.

It survived mass extinctions. It adapted to ice ages. It diversified across species, climates, and lifestyles.

What science had dismissed as “simple nutrition” was actually one of the most sophisticated biological communication systems on Earth.

Katie sometimes thought back to that quiet evening in 2008, alone in the lab, staring at numbers that didn’t make sense. She remembered the dismissive comments. The raised eyebrows. The shrugging indifference.

She was glad she hadn’t listened.

She didn’t just study milk.

She revealed that the most ancient form of nourishment was also the most intelligent. A dynamic, responsive conversation between two bodies that had been shaping development since the beginning of our species.

All because one scientist refused to accept that half the conversation was “measurement error.”

Sometimes, the most revolutionary discoveries don’t come from inventing something new.

They come from paying attention to what has always been there, quietly doing its work, waiting for someone to listen.

News

She kept finding women in laboratory photographs from the 1800s. Then she read the published papers—and every single woman had vanished. Someone had erased them from history.

That night, back in her small apartment, she wrote the question again at the top of a fresh page: Were…

In 1991, a 21-year-old posted “just a hobby, won’t be big” to an internet forum. Today, his “hobby” runs 96% of the world’s servers and 3 billion phones. You’ve used it today—and never knew.

He started with small goals. Make the computer talk to him properly. Make it handle tasks the way he wanted….

He called his wife ‘the most beautiful animal I own’ on live TV. She stood up, said ‘I have to leave,’ and walked off—while millions watched. That was 1972, and we’re still talking about it.

A small ripple of laughter moved through the audience. Not because it was funny, but because that was what audiences…

The bill said $0. She thought it was a mistake. Then she realized someone had finally seen her as human.

The Bill That Said Zero The bill said $0. For a long second, the woman at table seven thought the…

He stole her invention and told the judge no woman could design something so complex. She walked into court with 4 years of evidence—and destroyed him.

While other girls asked for dolls or ribbons, Margaret wanted a jackknife. A gimlet. Bits of scrap wood. She liked…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S SHOCKING ESCALATION: A Single Impeachment Move in Washington Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm No One Saw Coming

A Single Impeachment Move Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm in Washington Updated with today’s escalation, the showdown over HHS Secretary Robert…

End of content

No more pages to load