The neon sign out front had learned to stutter. It blinked Rosy’s Diner in bleeding red letters that glowed through rain-streaked glass, dimmed, then rallied in a shaky flare as if stubbornness alone kept the thing alive. Emily Carter watched it quiver in the window’s reflection while she wiped a circle on the counter that never stayed clean for long. The night had teeth. She could feel them in the wind rattling the hinges and in the rain drilling the parking lot like a thousand tiny hammers.

Inside, the world tried to pretend it was softer than it was. Coffee breathed steam from glass pots. The jukebox muttered a tired old jazz track. A truck driver in a damp hoodie cradled a bowl of chili. An elderly couple shared pie in the corner booth, leaning into each other in the way of people who had made long peace with time. In the far booth, a mother had fallen asleep holding a plastic fork, her small boy curled under her coat like a cat.

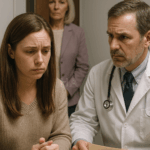

Emily’s smile was the kind you learn to wear like a uniform. She kept it bright enough to reflect in the chrome napkin dispensers and gentle enough not to startle the timid. It helped disguise the bruised ache behind her ribs where fear and worry stacked like plates that never got washed. The pharmacy had called that afternoon: the insurance won’t cover the extended dose. Her mother needed the pills or the lungs would drown themselves slowly. The number the pharmacist quoted had felt like a punch—more than a week’s pay for medicine that bought a week of breath.

She’d wanted once to be a nurse—white shoes, steady hands, a name tag that made people trust she could fix things. She’d wanted her own cafe too, where the coffee actually tasted like the labels promised and people left better than they arrived. But wishes, she’d learned, were thin blankets. They didn’t hold off the night.

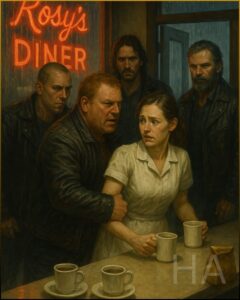

At 12:07 a.m., the door banged open so hard the bell above it choked on its own ring.

They arrived like a cold front—three men in damp leather, laughter like broken glass. The first had a neck tattoo that crawled toward a shaved scalp. The second wore a grin that didn’t touch his eyes. The third smelled of gasoline and stale beer and the kind of joy that only existed when it hurt someone else. They brought the weather with them and it sucked warmth from the diner so quickly Emily felt her knuckles pale around the coffee pot.

“Hey, sweetheart,” said the red-faced one, slamming his palm on the counter so the spoons rattled. “Serve us, b***h. Been waiting all day to see that pretty face.”

The words hung in the greasy fluorescent light. Boot soles squeaked. Somewhere under the counter, the ice machine thunked like a quiet fist. The elderly couple shifted in their seats and pretended to study the menu they’d memorized years ago.

Emily made her smile obedient. “Of course. Coffee to start?” Her voice tried to be normal and tripped on the way out.

They laughed because she made them feel big. The second one snapped his fingers an inch from her nose. “Extra sugar. We like it sweet.”

The third reached across and tugged her apron strings, fingers brushing the cotton at her waist. “Oops,” he said. “Loose.” His grin widened when she flinched.

She set cups in saucers with small careful sounds, poured coffee, slid a sugar caddy closer. They wanted reaction more than caffeine. When she stepped back, the red-faced one caught her wrist. His hand felt like a trap sprung.

“Where you running off to, princess?” he said softly, as if they were alone. “We’re just getting acquainted.”

Something hot and wild rose in her. No. But the diner was small and the night was loud and her mother’s breath was a clock ticking down. She pulled gently. “Please let go.”

It might have become a familiar story—fear stretching long, then snapping. Someone calling the cops who took too long. Someone else filming on a phone that only trapped shame in pixels without saving anyone. It might have ended with a cheap apology and a ruined night.

That was when the door opened again. Not a bang this time. A deliberate push. The bell made the sound bells make in churches after funerals, soft and hollow and promising something like mercy.

They walked in as a line—four bikers, road-worn, the rain sloping off their shoulders. Their jackets were black leather that had learned to bend, their boots scuffed by places where the world is made of dirt and grit. They didn’t look like the law. They looked like the way a warning sounds before it words itself.

The tallest moved with a measured economy that said he wasn’t there for theater. A scar curved over his left cheekbone toward his ear like something once tried to teach him fear and failed. His hair was iron-dark threaded with gray, beard trimmed to the patience of a man who did things the long way because it lasted. He saw everything—the clutch of Emily’s wrist, the way the old man in the corner had made his shoulders small, the way the truck driver was watching the door instead of his bowl, the way the child stirred under his mother’s coat at the disturbance.

The red-faced man followed the line of his gaze and smirked. Trouble, his grin said. The kind that makes you feel alive.

“Evenin’,” the scarred man said, voice quiet and unhurried, as if he were considering buying the diner and making a home for it. He stepped closer to the counter. “You might want to let go of the lady.”

“Or what?” The red-faced man squeezed. Emily’s breath stuttered. “Old man, you ain’t in this one.”

“I am now.” The scarred man didn’t raise his voice. He didn’t have to. It carried like distance does in a desert, clearly. “She’s working. You’re acting like trash. I don’t like trash.”

“I don’t like being told what to do,” the second thug said, pushing off his stool, his belt creaking. “And I really don’t like—”

The sound of a chair leg scraping the tile cut the sentence in half. The other three bikers had arranged themselves without anyone noticing exactly when—one leaning a shoulder against the jukebox, another with his arms folded loosely, another idly examining a rack of postcards by the register as if planning a vacation. Their silence made a new kind of noise in the room: the math of consequences.

The scarred man tilted his head. “Walk away,” he said. “You get to keep your teeth.”

There is a point in every oncoming storm where it might break left or right, where heat and pressure argue in the air and for a second the whole sky leans toward mercy. The red-faced man looked into that second and flinched at what stared back. Something in him calculated. The world was wide and full of places where he could be brave without payment. He released Emily’s wrist so abruptly she nearly stumbled.

“Fine,” he spat. “Coffee sucks anyway.” He knocked his cup so the coffee sloshed, and his men laughed too loud to cover their backpedal. They pushed through the door into the rain, dropping a curtain of curses that sounded like boys whistling in a graveyard. Their taillights smeared red as they fishtailed out of the lot, then they were gone—just thunder and wet asphalt and the diner exhaling all at once.

Silence held. The jukebox remembered its job and found the saxophone again. The trucker coughed because he’d forgotten to breathe.

Emily’s hand shook. She placed the pot back on its warmer and stared as if the glass were a species she’d never seen before. When she looked up, the scarred man was watching her with a softness that had no pity in it, only recognition—as if he’d stood somewhere like this before and knew the shape of it.

“You okay, sweetheart?” he asked.

She nodded out of habit. Her mouth trembled. “Thank you. You didn’t have to.”

He shook his head. “No one should have to take that kind of disrespect.” He slid onto a stool. “Four black coffees,” he said, glancing back at his men with a ghost of a smile. “And whatever pie hasn’t given up yet.”

Relief came clumsy and too fast; it made her want to sit down on the floor and cry. Instead, she poured. Her hands steadied with the repetition. Mugs. Saucers. White crescents of steam. The men accepted them the way thirsty people accept a clean glass of water.

They weren’t much for talking. They ate pie like a sacrament, heads bent, the forks making small bright sounds against the plates. The one at the jukebox—skinny, with clever eyes—picked a song you could drive to. The big one with the forearms of a mechanic studied the laminated menu as if it revealed the weather. The third—broad-shouldered, a healed split in his eyebrow—murmured something about the pie crust and got a chorus of grunts that, translated, meant: It’s good.

When the rush of adrenaline drained, Emily realized she was crying. Not the hot, embarrassed leaks she’d learned to swallow. Quiet tears that slid without drama and dripped from her jaw. She swiped at them with her wrist. The scarred man saw, and his face did a thing she hadn’t expected—it softened another notch, an inside door opening.

“Rough life?” he asked, the words shaped to fit in her hands without spilling.

She had trained herself not to tell strangers the truth. In this job, the truth got you offered rides you shouldn’t take, or pity you couldn’t use. But the way he asked loosened something. The truth wasn’t heavy when you set it in front of someone who could lift it.

“My mom,” she said, throat thick. “She’s sick. The medicine’s… It’s a lot.” She laughed a small bent laugh. “Everything’s a lot. Rent. Hours. Men who think serving food is the same as serving them.” She stopped. It felt dangerous to let the words out, like a dam cracking.

He didn’t interrupt. He didn’t offer solutions or say it’ll be okay (which always meant you’re alone). He listened like a man changing a tire in cold rain—focused, hands sure, not frightened by the mess.

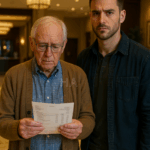

When the coffee was gone and the pie looked like aftermath, he reached into his jacket and took out a small envelope, the kind that looked like it belonged around a birthday card or a letter from a far place.

“This is for you,” he said, setting it on the counter. “For the medicine. For your mom.”

Emily flinched from it as if it might burn. Pride and survival had always wrestled inside her; one kept her standing, the other kept her fed. “I can’t—”

“You can,” he said, already sliding off the stool. “And you will.”

He left her with a nod and a line that felt like a promise rather than a command. The others rose with the synchronicity of a flock. He tapped the rim of his mug in gratitude. “Good coffee,” he said.

She caught the door with a hand and called after them because the thank you clawed at her throat. “Wait—your name—”

He paused with one palm on the chrome handle. The rain had softened to a trembling curtain. “Call me Mason.”

The bikes coughed, then growled, then roared into the night. The bell settled. The neon sign blinked bravely.

Emily stared at the envelope until curiosity wrestled fear and pinned it. Inside, a note in careful block letters: From the Riders’ Brotherhood. You’re stronger than you know. Keep fighting. Beneath the words lay a stack of hundred-dollar bills, not ostentatious, just enough. Enough to breathe. Enough to sleep one night without turning over stones in her brain for money that wasn’t there.

She pressed the note to her chest and stood for a time like that, the rain and the tears making the same warm wet on her face.

The diner did what diners do: it shrugged, wiped its counters, and kept feeding whoever wandered in bleeding or smiling or both. But word had a way of traveling—stories slipped across truck stop CBs and between knuckles clutching mugs, changed slightly each retelling the way blues riffs do and still kept their bones. “The night the bikers walked in,” people began to say. “The waitress with the brave eyes.” “The one who smiled like she was holding a door for someone in a hurry.”

A week later, the thugs returned. Not all storms learn. Pride has a short memory, and humiliation is a bad teacher when it comes without a lesson plan. They slipped in quiet this time, no bell-slam, no laugh-shards, just a thin film of resentment lining their mouths.

The lunch rush had thinned to the quiet hum between rhythms. The truck driver from that night looked up and looked down quickly again, the way deer look at headlights. The elderly couple wasn’t there; Tuesdays were their daughter’s days. The boy with the clever eyes at the jukebox—one of Mason’s men—sat alone at the corner booth with a bowl of stew and a glass of water, reading an owners’ manual like it was poetry. He met Emily’s glance and dipped his chin: you’re not alone.

The red-faced man planted himself at the counter and flattened his hands as if about to pray. He smiled and it had too many teeth. “Miss me?”

“Coffee?” Emily asked, voice neutral, neutral, neutral.

He leaned in. “I missed saying hello proper.” His hand reached again toward her waist as if his body had only learned that one move.

Two things happened at once. The bell chimed. And the clever-eyed biker at the booth stood without haste but with purpose.

Mason’s boots found the threshold as the red-faced man’s fingers curled. One look at Mason’s face erased the smirk. Mason could be gentle around a person in pain. He could also be a door that didn’t move when you pushed it with all your weight.

“You and me,” Mason said, stepping in close enough that rain sequins clung to his beard, “we’re going to have a small talk about math. The sort you do without numbers. Add your actions, subtract the excuses, multiply the consequences. Understand?”

The red-faced man made a show of scoffing, but the breath he took was shaky. The clever-eyed biker had moved near enough to be a shadow. The third biker—broad-shouldered one—entered with a small brown paper bag whose grease spot announced something like burgers. He set it down and took off his gloves as if he had all the time in the world to decide whether he would use his hands for eating or something else.

“This place,” Mason said, not blinking, “feeds people who are tired and kind and dumb with love for their families and mean and lonely and lost. It feeds all of them. It is a shelter. You will treat it like one. Or you will not come here. Those are your choices.”

There are men who only understand a fist. Mason believed in fists for last resort, not first. His voice did the work. It carried the weight of roads and winters and the mornings after fights when you learned what you’d actually won. The red-faced man stared and stared longer and finally looked away first. He had found new places to be brave that did not involve Mason.

“We’re leaving,” he said, pretending to discover the door. He retreated not quite as fast as a run. The others scuffed their way out after him, the bell clanging like relief. You could feel the diner lift slightly, like a boat after a weight steps ashore.

Mason’s eyes found Emily’s. She was breathing too quickly again. He set the brown bag on the counter and nodded at it. “Lunch. Sorry it’s late.”

She laughed, a little broken bit of sound. “You’re not my guardian angels,” she said, dabbing her cheeks with a napkin. “Right?”

“No wings,” the clever-eyed one reported, looking under his jacket. “Just patches.”

She glanced at the rockers sewn into their leather—their name stitched in a curve like a horizon: Riders’ Brotherhood. It fit, she thought. Not a gang. A promise.

“Why… me?” she asked. “There are a thousand places where bad things happen, a thousand people who need… this.”

Mason shrugged. “Because we were here,” he said simply. “Because you were here. Because we’re the kind of men we want to be when we look at ourselves later.”

It was not romantic and it felt truer than any love letter.

They ate in a corner booth, the four of them, while she refilled their water glasses and the afternoon unwound into the soft blue of coming evening. Mason listened as she told him small things—how her mother loved old westerns and sang under her breath when she thought no one listened, how the landlord’s dog had learned to wait for scraps behind the back door, how the neon sign sometimes made the “R” in Rosy’s blink out so it read osy’s and sounded like a sigh.

“Call a union,” the broad-shouldered biker said when she spoke of the night shifts and the tips that went missing into the owner’s pockets. “Call a lawyer.”

“Call us,” the clever-eyed one added, wiping stew from his chin. “We’ll stand outside and look ugly while you talk.”

She smiled in the exact way people smile when they are not used to people standing anywhere nearby at all.

The envelope bought medicine and a humidifier and new pajamas with soft cuffs for nights when breathing felt slippery. Her mother cried when Emily told her about the bikers. Then she scolded Emily for letting strangers give her money. Then she put her hand over Emily’s and squeezed so hard you could read all the words she didn’t say in the indentations her fingers left on Emily’s skin.

The diner changed, not in the way paint makes a place new but in the way forgiveness makes it livable. People looked up when the bell rang instead of down. A jar appeared by the register with a hand-lettered sign: Neighbors’ Fund—Leave some, take some. It wasn’t just for medicine. It was for whatever broke. You could tell who contributed by the way they pretended not to; you could tell who took by the relief on their faces like someone had undone a tight knot behind their hearts. Emily watched the jar rise and fall like a tide that obeyed better moons than money usually did.

Patches of leather started appearing around lunchtime like wildflowers in a stubborn yard. Sometimes the Brotherhood came in as a quartet, sometimes in twos, sometimes Mason alone like a small weather system. He never sat where he could see himself in the window. He sat where he could see the door. He always left the corner booth nearest the kitchen for the elderly couple who had made it their kingdom. He tipped well, but there was no theater in it. He paid for the trucker’s chili once with a casual toss of a bill and never looked over to watch the reaction.

“You’re different when they’re here,” the short-order cook said one Friday, flipping a burger with a grunt. “You stand taller.”

“I am taller,” she said, surprised it was true. “I think I forgot.”

“Don’t forget again,” he said, sliding the plate onto the pass with a thud that sounded, for once, like affection.

The thugs didn’t return a third time. Maybe they went looking for other doors. Maybe they learned addition.

Months passed the way months do when they’re full—fast and full of details that knit into something that looks like a life when you step back. Emily found the rhythm she’d wanted, not the exact one she’d imagined—the nurse’s shoes were still an idea—but a rhythm not so far from it. She learned the comings and goings of the Brotherhood the way you learn birds’ calls by season. She learned Mason’s face well enough to see the days when he’d slept poorly and to pour a refill before he asked. She learned how to say thank you with a look, because some debts were not for paying back with money but with a kind of equal courage.

The night her mother had to be moved to better care—a place with windows that made a room into a world—the Brotherhood came in quiet after closing. They lifted boxes. They held doors. They were there in the most holy way, which is to say unasked and right on time. Mason fixed a wobble in the wheelchair with a spare bolt from his pocket. When Emily hugged him in the parking lot under the obedient moon, he cleared his throat and patted her back twice as if to make sure she was real.

“You saved us,” she whispered.

“We didn’t,” he said, stepping back. “We reminded you. You saved yourselves.”

When he rode away, she realized his scar had never made him look dangerous to her—not once. It made him look like a man who had already met the worst nights and survived the introduction.

It might have ended there—a neat arc, a lesson with a bow. But the world is messier and kinder than stories sometimes allow, and kindness, once set in motion, is a wheel that keeps turning until something equally earnest stops it.

So when the young man came in one evening with a backpack and eyes like someone had kicked his dog, Emily recognized the posture immediately. He was twenty if a day, hair hacked in a bathroom mirror, hands that couldn’t stop wiping themselves on his jeans. He took a seat and pushed a crumple of bills at her that smelled like engine oil and longing.

“What can I get for this?” he asked, as if he’d been practicing asking all day.

She looked at the money and then at him and then past him at the jar. “A plate of pancakes that will keep you from falling down,” she said. “A side of bacon to remind you you’re still on this side of the horizon. A glass of milk because your mother would tell me to.”

He blinked, stunned by the sudden generosity of the universe. “Why?”

“Because we were here,” she said, and the words felt like a relay baton passed cleanly, no drops.

Later, when the Brothers came by and Mason saw the boy’s face loosening into color, he looked at Emily and tipped his chin the way you do when you witness a promise kept.

“Proud,” he said, so softly she might have imagined it.

She wasn’t the same woman who had stood shaking by the coffee pot months ago. She moved with the steadiness of someone who knew she had a wall behind her—four men in leather, a jar by a register, a community that had decided a small diner could be a church where the sacrament was coffee and pie and showing up.

On rare late nights when the neon didn’t stutter and the jukebox remembered ballads, Emily would imagine that other life—the nurse’s shoes, the clipboard, the quiet competence. It didn’t hurt anymore to picture it. She wasn’t mourning it; she’d found a different way to be exactly what she’d wanted: someone who made other people breathe easier.

Sometimes the bell would ring and the rain would come in on the backs of men who had learned to listen more than speak. Sometimes the bell would ring and it would be a kid with a skateboard and eyes that asked for permission to exist. Sometimes it would be the landlord’s dog, who had learned to push the cracked door with his nose, his paws leaving wet prints on the tile. All of them got fed.

Once, late—so late the highway sounded like the ocean—Mason lingered by the register after paying, his palm heavy with exact change.

“You ever think about moving on?” he asked. Not because he wanted her to. Because he wanted to know her answer.

“Every day,” she said. “And every day I stay. Not because I have to. Because I want to.”

He nodded like a man pleased by a torque wrench’s click. “Then it’s the right place.”

He tucked a card under the jar. White, plain, his name and a number. No club insignia, no bravado. It looked like the kind of card a person gives when they mean it. “If anyone forgets their math,” he said, “call.”

She slid the card into the cash drawer not because she feared she’d need it, but because the sound the drawer made when it closed felt like a home finding its latch.

The neon outside hiccuped, then brightened. The rain kept falling somewhere beyond the reach of the warm windows, trying to wash the world clean. Inside, kindness had learned to roar—and, when it needed to, to purr—and the sound of it made a shelter large enough to hold anyone who pushed the door and came in from the weather.

News

The Billionaire Came Home Early — and the Maid Whispered “Stay Silent.” What He Found Will Leave You Stunned

The Billionaire Came Home Early — and the Maid Whispered “Stay Silent.” What He Found Will Leave You Stunned Richard…

Bride Mocked by Groom’s Family, Unaware of Who She Really Was — Until She Canceled the $950 Million Deal

Bride Mocked by Groom’s Family, Unaware of Who She Really Was — Until She Canceled the $950 Million Deal The…

“She’s With Me” — The Night a Single Dad Changed a Billionaire’s World

“She’s With Me” — The Night a Single Dad Changed a Billionaire’s World The Grandview Restaurant shimmered beneath its chandeliers…

The Forgotten Bride: A Heart-Touching Story of Love, Family, and Fate

The bitter Nebraska wind howled across the plains, sweeping up dust and shards of snow that slashed through the air…

CEO Mocked Single Dad on Flight — Until Captain Asked in Panic “Any Fighter Pilot On Board”

The hum of the jet engines was the kind of sound you don’t notice until something goes wrong. On Flight…

Poor Single Dad Entered a Luxury Store — Everyone Laughed Until the Owner Came Out

Poor Single Dad Entered a Luxury Store — Everyone Laughed Until the Owner Came Out The bell above the glass…

End of content

No more pages to load