Bumpy lifted two fingers.

Not toward the gun.

Toward the window crank.

“Stop,” he told the driver, calm as if he’d just spotted a friend.

Bub started to protest.

Bumpy didn’t look at him. “I said stop.”

The Cadillac came to a quiet, obedient halt in the middle of Lenox Avenue, and for half a second Harlem itself held its breath.

Bumpy rolled down the back window. The cold rushed in like it had been waiting for permission.

“Ma’am,” Bumpy called, voice steady, not loud, but it carried. “You’re standing in the middle of the street in this weather. You need help?”

The woman took a careful step toward the car, then another, moving like every joint objected. When she reached the window, the wind shook her so hard her words came out in pieces.

“Mr. Johnson,” she said, and somehow the name sounded like both fear and hope. “Sir. I know who you are. Everybody in Harlem knows who you are. I’m sorry to stop your car like this, but I didn’t know what else to do.”

She swallowed, lips pale. Her eyes were bright with tears she refused to let fall first.

“I haven’t eaten in three days. My electricity been off a week. My heat been off ten days. I’m in my apartment with no power, no warmth, and I… I can’t afford food.”

Her breath hitched.

“I came out here because I was hoping… maybe if I could find you… you might help me.”

Then, like it was the only request she dared make in a world that punished people for needing anything, she whispered:

“Just one bread, Mr. Johnson. That’s all I need. Just one bread so I can eat something. Please.”

Bumpy stared at her.

He had seen men beg for money with teeth full of lies. He had seen women cry with eyes that stayed dry. He had seen children trained to perform hunger like a street act.

This wasn’t that.

This was a Harlem grandmother starving in a dress that belonged indoors, bruised by someone who didn’t respect age, standing in the street to stop the car of a man whose reputation could make grown men cross the avenue.

And for reasons he couldn’t have explained without sounding foolish, something inside Bumpy’s chest tightened, not like fear, but like recognition. Like he was looking at a piece of his own past, dragged into the present and forced to stand still.

“Get in the car,” he said.

The woman blinked. Her eyes flicked to Bub, to the driver, to the gleam of expensive leather and danger.

“I… I don’t want no trouble,” she stammered.

“You’re going to freeze to death out here,” Bumpy said, more firm now. “Ain’t nobody got time for pride with the weather like this.”

The cold won the argument. Fear came second.

She climbed into the back seat with the careful slowness of someone whose body had been treated like it didn’t matter for a long time. The warmth of the car hit her like a wave, and she started crying immediately, not dramatic sobs, just the kind of quiet crying you do when your body realizes it might survive another day.

Bumpy shrugged off his own overcoat, an expensive camel-hair thing that probably cost more than some people’s rent for half a year, and wrapped it around her shoulders.

“What’s your name, ma’am?” he asked.

“Elizabeth Carter,” she said, teeth chattering. “I live at 347 West 134th Street. Apartment 4B. I’m seventy-two. Been in Harlem since 1904. Came up from Virginia. Worked domestic for white families downtown until I got too old.”

She looked down at her hands. They were cracked from cold and work and cheap soap.

“Now I live on nothing. No pension. No savings. City welfare gives me eleven dollars a month, but my rent is eight. That leave three for everything else.”

Three.

Bumpy repeated the number in his head like it might change if he tried it from a different angle.

Three dollars a month for food, electricity, heat, clothing, medicine. For life.

And she’d been managing… until winter sharpened its teeth and decided to test who could endure.

Bumpy’s eyes drifted to the bruise on her cheek again.

“Mrs. Carter,” he said, careful, “that mark on your face. How’d you get it?”

Her fingers tightened on the coat, clutching it like proof that warmth existed.

“It’s nothing,” she lied, too quickly. “I fell.”

Bumpy’s voice stayed gentle, but the air around it changed. “I been around accidents, ma’am. That ain’t an accident.”

She looked out the window like Lenox Avenue might rescue her from the truth.

“Somebody hit you,” Bumpy said. “Who was it?”

The crying came harder now, not from relief, but from shame, from humiliation, from holding something terrible alone because you think speaking it will make it more real.

“My son,” she whispered finally. “Edward. He’s forty-three. He’s… he’s an alcoholic.”

The word tasted bitter on her tongue.

“He been drinking since he was seventeen. Lost every job. Can’t keep a place. Sleeps on the street most nights.”

Her voice shook like the car itself.

“He come to my apartment asking for money. For liquor. And when I say I don’t have it, he… he get mean.”

She closed her eyes.

“Two days ago he came at three in the morning. So drunk he couldn’t stand. Demanding money. I told him I ain’t got nothing. I’m barely surviving myself.”

A breath. A sob.

“And he hit me. Knocked me down. I hurt my hip on the table. Then he searched my apartment till he found the dollar I had hidden in a coffee can for emergencies.”

Her eyes opened, wet, furious at herself for saying it out loud.

“And he took it.”

Bub’s head turned slightly, as if the words had weight.

Bumpy’s face went still.

Not angry yet.

Worse.

Cold.

There were lines in Bumpy Johnson’s world. He lived on the wrong side of most of them. He trafficked in fear and profit and violence, and he didn’t pretend otherwise.

But he had lines.

Children.

Elderly.

The kind of people the world already pushed around without needing help.

Bub knew that expression. He had seen it before a man got hurt badly and deserved it.

Bumpy leaned forward, elbows on his knees, studying Elizabeth like he was trying to see time itself written in her wrinkles.

“Tell me about your son,” he said. “Not what he did. Tell me who he was before the bottle got him.”

Elizabeth blinked, confused by the question. But something in the way he asked, like he was not simply collecting evidence but searching for a missing person, made her answer.

“Edward was a good boy,” she said softly. “Smart too. Finished high school, one of the few colored boys in his class. He wanted to be a teacher. Mathematics. He was always good with numbers.”

A little smile tried to appear and failed.

“But there weren’t teaching jobs for colored men. Not real ones. So he worked docks. Factories. Janitor work downtown. Hard work. Low pay. White men treating him like he was stupid even though he was brighter than most of them.”

Her voice roughened.

“And somewhere along the way, he started drinking. First just to take the edge off. Then more. Then always.”

She wiped her eyes with the sleeve of Bumpy’s coat.

“Sometimes,” she admitted, “when he sober for a few hours… I see flashes of who he used to be. He still in there somewhere. Buried.”

Then her shoulders sagged.

“But I don’t know how to reach him no more. I’m too old. Too poor. Too tired. And now he hurting me.”

Bumpy sat back.

Outside, Harlem moved on. A man pushed a cart. A kid ran with his scarf trailing like a ribbon. A couple argued under their breath like their words were expensive.

Inside the Cadillac, the air felt heavier than it should.

Bumpy pulled out his wallet and removed five crisp twenty-dollar bills. He held them out.

Elizabeth’s eyes widened like he’d offered her a piece of the moon.

“Mr. Johnson, I can’t— I just asked for one bread.”

“You take it,” Bumpy said, voice leaving no space for debate. “You pay your electric bill today. You pay your landlord so he turn the heat back on. You buy yourself a warm coat and proper shoes. You buy groceries. Real groceries.”

He glanced at her hip as if he could see the pain through fabric.

“And you buy medicine for that hip.”

Elizabeth’s hands trembled as she took the money.

“I don’t know how to thank you.”

“You don’t,” Bumpy said. “You just live.”

Then his voice tightened.

“And you don’t give a single dollar of that to your son. You hear me?”

Elizabeth nodded quickly, fear flickering. “I promise.”

Bumpy’s gaze stayed on her until she looked away, because promises were easy, and desperation was stronger than most vows.

He leaned forward and spoke to the driver. “Take her home. Wait. Make sure she put that money somewhere safe. Then take her to the electric company office, then wherever she need. Grocery, clothing, pharmacy. And make sure nobody bothers her.”

“Yes, Mr. Johnson,” the driver said.

Bumpy looked back at Elizabeth. “If Edward come around again, you send somebody to find me. Palm Cafe. You say Elizabeth Carter needs Bumpy.”

Elizabeth swallowed. “Mr. Johnson… please don’t hurt him.”

“I ain’t going to kill your son,” Bumpy said, and there was something almost tender in the way he said it, as if he surprised himself. “But I’m going to make something clear.”

He paused, then asked quietly, “Where he usually drink?”

Elizabeth hesitated, torn between protecting her child and protecting herself.

“There’s an alley behind Cohen’s liquor store on 133rd,” she said at last, voice small. “Between Lennox and Seventh. The drunks gather there.”

Bumpy nodded once.

“Go get warm, Mrs. Carter.”

The car door closed. The Cadillac pulled away, carrying Elizabeth toward heat and light and the bewildering weight of a hundred dollars.

Bumpy watched the street for a moment. Then he turned to Bub.

“We taking a walk,” he said.

Bub’s hand settled comfortably near the .45. “Where to?”

“133rd,” Bumpy replied. “We need a conversation.”

The Alley Behind Cohen’s

The alley behind Cohen’s liquor store was exactly the kind of place the city pretended not to have.

A narrow cut between buildings where sunlight arrived like an apology. Garbage piled in corners. Broken bottles glittered like cheap jewels. Men sat on cardboard, passing brown paper bags like communion.

When Bumpy and Bub stepped into the mouth of the alley, the air changed immediately.

It always did.

Men who had been laughing went quiet. Men who had been leaning stood up too fast. A survival instinct sharpened by poverty and bad luck told them that if Bumpy Johnson walked into your corner of the world, your corner might stop being yours.

Three of them shuffled away without being told, backs hunched, eyes averted.

The fourth man didn’t move.

Edward Carter sat with his back against brick, bottle clutched in his hand, face unshaven, clothes filthy, body trembling from cold or withdrawal or both. He was talking loudly, slurring through a story about some fight he’d supposedly won years ago.

He didn’t notice the alley emptying.

He didn’t notice the shadow falling across him until it blocked what little light there was.

Edward squinted up, annoyance forming, then confusion, then the slow bloom of terror as his brain finally assembled the face.

He tried to stand.

His legs betrayed him. The bottle slipped, shattered on the ground, whiskey bleeding into the dirt.

Bumpy’s voice was quiet and deadly calm.

“Edward Carter?”

Edward licked his split lips. “Yeah. Who… who asking?”

Bumpy reached down and grabbed him by the front of his shirt, lifting him with a smooth, terrifying ease. Edward’s feet scrambled for traction, finding none.

“Your mother seventy-two,” Bumpy said, and each word landed like a hammer. “She starving. She freezing. She got three dollars a month after rent. Three.”

Edward’s eyes darted, searching for an exit that didn’t exist.

“And you went to her place drunk,” Bumpy continued, “demanding money. When she said she ain’t got it, you hit her. Knocked her down. Hurt her hip. Bruised her face.”

Bumpy leaned in. Edward could smell cigar and winter and something sharper: consequence.

“Then you stole the only dollar she had hidden.”

Edward’s mouth opened. Closed. Opened again.

“I didn’t mean to,” he whispered finally. “I was drunk and I needed—”

The slap came so fast Edward didn’t see it. The sound cracked in the confined space like a small explosion. Edward’s head snapped sideways, blood appearing at his lip like a sudden confession.

Edward cried out, hands flying up too late.

Bumpy hauled him closer.

“That’s the last time you ever touch your mother,” Bumpy said, voice low. “The last time.”

Edward sobbed, blood and tears running together.

“I understand,” he choked. “I’m sorry. I swear—”

“Sorry is just sound,” Bumpy said. “Ain’t worth nothing.”

He released Edward, letting him stumble back against the wall.

Then, to Edward’s shock, the temperature of Bumpy’s voice changed. Not warm. Not kind.

But… measured.

“You forty-three years old,” Bumpy said. “You living like you already dead. You could have been something. Teacher. Numbers. Your mama told me.”

Edward wiped his mouth with a shaking hand. “What you know about it?” he snapped, anger flaring like a match in a storm. “What you know about being a colored man in this city? I did everything right. High school. Work. And it didn’t matter. White men treated me like dirt. No opportunities. So yeah, I drank. What’s the point?”

Bumpy studied him, eyes narrowed.

“You want to know what I know?” he said. “I grew up in South Carolina picking cotton for white men who thought they owned us. We went hungry so often hunger felt normal. I came to Harlem with nothing.”

He stepped closer, voice sharpening.

“This country unfair. You right. It don’t hand out dignity to colored men like you and me. But you got two choices. You let that unfairness kill you, or you find a way to live anyway.”

Edward’s breath hitched.

Bumpy’s next words fell like a verdict.

“Tomorrow morning, 6:30, you going to Sam’s restaurant on 135th and Lennox.”

Edward stared, confused. “What?”

“Sam need a man to haul ice. Carry sacks. Wash dishes. Mop floors. Hard work. Honest work. Pays twenty-five a week.”

Edward’s eyes widened as if Bumpy had suggested magic.

“A job?” he whispered, almost offended by the idea that life could still offer him anything.

“You show up clean,” Bumpy said. “Sober. You work six days a week. Sam pay you every Friday.”

Edward’s voice cracked. “Why?”

Bumpy’s stare didn’t soften. “You ain’t doing this for you.”

He nodded toward the street, toward the invisible apartment where Elizabeth Carter had been freezing in darkness.

“You doing it for your mother.”

Bumpy reached into his pocket and produced a ten-dollar bill, holding it out like a rope to a drowning man.

“Go find a bath house. Clean up. Shave. Find a flop house with a bed. Don’t spend this on liquor. Don’t even breathe near a bottle.”

Edward’s hand hovered before taking the money, trembling.

“And listen,” Bumpy added. “Every Friday, out that twenty-five, you give ten to your mother. Every Friday. You miss one payment, we have another conversation.”

Edward swallowed hard. “I’ll do it,” he said, voice raw. “I swear.”

“Don’t swear to me,” Bumpy said. “Swear to her.”

Then he turned, as if the alley suddenly bored him, as if mercy was just another business transaction he’d finished handling.

Bub followed, heavy and silent.

Behind them, Edward slid down the wall and pressed the ten-dollar bill to his chest like it might stop his heart from breaking open.

One Night, One Choice

Edward didn’t sleep.

Not because he didn’t have a bed. He bought one with that ten dollars, a thin mattress in a flop house on 152nd Street, a room that smelled like bleach and old sorrow.

He didn’t sleep because his body screamed for whiskey.

Because his hands shook.

Because his mind kept replaying his mother’s bruise.

Because Bumpy Johnson’s voice kept repeating a sentence that felt impossible and terrifying:

Tomorrow morning. 6:30.

At some point close to midnight, Edward found himself outside a liquor store, staring through the glass at bottles lined up like soldiers.

His mouth watered. His hands clenched.

A familiar thought slithered up: Just one. Just to calm down. Just to stop the shaking. I can still go to Sam’s tomorrow.

Then another thought followed, quieter but heavier:

If I drink, I don’t just lose a job. I lose my mother.

And somewhere under that, deeper, the truth he’d tried to drown for years:

If I drink, I stay the man who hit her.

He turned away so fast it almost looked like running.

He walked until his legs burned, until the city blurred, until his craving became a dull roar instead of a command.

Then he waited for dawn like a man waiting for judgment.

Sam’s Restaurant

At 6:15 a.m., Edward stood outside Sam’s restaurant in the pre-dawn cold, staring at the window like it was a gate to another life.

At 6:25, he inhaled and stepped inside.

Sam was a big Greek man with gray hair and hands that looked carved out of labor. He studied Edward for a long moment, then nodded like he’d already decided something.

“You Edward Carter?” Sam asked.

“Yes, sir,” Edward said quietly. “Mr. Johnson told me—”

“Yeah,” Sam interrupted. “Bumpy called.”

Sam leaned closer, voice low. “I don’t care what you did yesterday. I care what you do today. You show up on time. You work. You don’t bring trouble in my place. You do that, you get paid.”

Edward nodded, throat tight. “Yes, sir.”

Sam gestured toward the back. “Come on.”

The work hit Edward like a wall.

Ice blocks heavier than regret. Sacks of flour that felt like they were filled with stones. Dishwater scalding his hands. Nine hours of standing that made his feet scream.

By noon, he cried quietly over the sink, sweat and tears mixing like the body couldn’t tell the difference between pain and grief anymore.

He wanted to quit.

He wanted to crawl back into the familiar darkness.

But then he pictured his mother in her thin house dress, wrapped in Bumpy’s expensive coat, crying because warmth had returned to her skin.

And he kept going.

At 3:30 p.m., Sam clapped him once on the shoulder.

“You did good,” Sam said gruffly. “You complained some, but you didn’t quit.”

Edward swallowed. “I’ll be back tomorrow.”

“You better,” Sam said, and there was a hint of something like approval behind the threat.

Edward walked out into Harlem with his hands bandaged and his body aching, and for the first time in fifteen years, he felt something that wasn’t liquor.

He felt earned tired.

Friday, Ten Dollars, A Doorway

By Friday, Edward’s hands were callused, his back still aching but no longer collapsing, and his mind… quieter.

At 3:30, Sam handed him an envelope.

“Twenty-five,” Sam said. “Count it if you want.”

Edward opened it with shaking hands.

Five fives.

Clean money.

Honest money.

His throat tightened so hard he couldn’t speak.

Sam snorted. “Don’t cry in my office. Go on. And remember what you owe your mother.”

Edward nodded, then left like the envelope was fragile and holy.

He climbed four flights of stairs at 347 West 134th Street and stopped in front of apartment 4B, heart pounding like he was about to be sentenced.

He knocked gently.

“Who is it?” Elizabeth called, fear sharp in her voice.

“It’s Edward, Ma,” he said through the door. “I’m not drunk. I’m not here for trouble. I’m here to give you something.”

The door opened a crack.

Elizabeth peered out like she expected a stranger wearing her son’s face.

But Edward was shaved. Sober. Eyes clear.

He pulled out ten dollars and held it out with both hands, like offering peace.

“Mr. Johnson got me a job,” Edward said, voice shaking. “At Sam’s. I worked all week. This is for you. I’m going to bring you ten every Friday. Every Friday as long as I’m breathing.”

Elizabeth stared at the money, then at his face, then at the space behind him like she expected the old world to rush in and take this away.

“Ma,” Edward whispered, and his voice cracked open. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry for what I did. I can’t undo it. But I can… I can be better.”

Elizabeth’s hands trembled as she took the ten.

Then, very slowly, she stepped forward and hugged him.

Not cautiously.

Not politely.

She hugged him like a mother hugging a child she thought she’d buried.

“My boy,” she whispered into his shoulder, crying. “My Edward.”

Edward closed his eyes and held on like he might fall apart otherwise.

For a long moment, in a narrow Harlem doorway, winter lost its grip.

Years Like Bricks

Edward worked at Sam’s restaurant for eleven years without missing a single day.

Every Friday at 3:30, Sam paid him.

Every Friday at 4:00, Edward climbed those stairs and handed his mother ten dollars.

He stayed sober not because the desire vanished, but because he learned a hard truth:

Craving was loud, but love could be louder if you listened long enough.

In 1952, Sam promoted him. Forty dollars a week. Edward kept giving his mother ten, and for the first time in a long time he had enough to rent a small room of his own instead of sleeping in flophouses.

Elizabeth’s apartment became warm.

The lights stayed on.

There was meat sometimes. Vegetables. A coat hanging by the door.

Neighbors noticed. Word traveled. Harlem always watched, even when it pretended not to.

People whispered the story the way people whisper about miracles they don’t fully trust:

Bumpy helped her.

Bumpy scared her son straight.

Bumpy Johnson, of all people.

And if you listened closely, you could hear something else underneath the gossip:

A hunger for proof that the world could be interrupted. That cruelty wasn’t the only thing with power.

March 3rd, 1955

When Elizabeth Carter fell ill with pneumonia, she was eighty years old and tired in a way that no sleep could fix.

Edward visited every evening after work, bringing soup from Sam’s, sitting beside her bed in the clean apartment that had once been a cold, dark box.

On March 3rd, 1955, Elizabeth died with her son holding her hand.

Warm.

Fed.

Not afraid.

At Mount Olivet Baptist Church, the funeral was small. Neighbors, old friends, women who remembered Elizabeth as a young domestic girl with bright eyes and tired feet.

Edward stood at the front, shoulders squared, grief heavy but clean.

And in the very back of the church, half in shadow, stood Bumpy Johnson.

He didn’t come forward. He didn’t make a scene. He didn’t need to.

After the service, as the crowd filtered out, Edward approached him.

“Mr. Johnson,” Edward said quietly. “Thank you for coming. It would’ve meant a lot to my mother.”

Bumpy nodded once. “She was a good woman.”

Edward swallowed, eyes burning. “Because of you, I got to take care of her these last years. She didn’t die cold and hungry. She died with me beside her.”

Bumpy’s gaze stayed steady. “You repaid me by showing up every day. By staying sober. By bringing her that ten every Friday.”

He paused, and for a second his voice softened like a coat being placed gently on someone’s shoulders.

“Most people waste chances. You didn’t.”

Edward’s chest tightened. “I can never repay you.”

Bumpy looked past him, toward the church doors, toward Harlem, toward a world that still didn’t feel fair.

“Some debts don’t get repaid,” Bumpy said. “They get honored.”

Then he turned and walked away, disappearing into the city like a rumor wearing a suit.

The Envelope at the Palm Cafe

Edward Carter bought a small grocery store on 138th Street in 1958.

He ran it quietly. Decently. He kept a little chalkboard sign by the counter that always had the same message in careful handwriting:

“NO CREDIT, BUT ALWAYS KINDNESS.”

People thought it was corny.

People also kept coming back.

Every year on February 4th, Edward dressed in his best suit and walked to the Palm Cafe.

He didn’t ask for Bumpy. He didn’t need to. Harlem handled messages the way it handled everything else: efficiently and without paperwork.

Edward left an envelope at the bar.

Inside was fifty dollars and a note that said:

Thank you for giving me my life back.

He never asked if Bumpy received it.

He didn’t need the confirmation.

Some gratitude didn’t require applause. It just required repetition, the way a prayer did.

Outside, Harlem kept changing. Buildings rose. Buildings fell. Men came home from wars and went back out to fight different kinds. Winters stayed sharp. Poverty stayed stubborn.

But the story stayed too.

The story of an old woman in a thin house dress who stopped a black Cadillac in the middle of Lenox Avenue and asked for one loaf of bread.

The story of a feared man who chose, for once, to be something other than feared.

The story of a son who learned that redemption wasn’t lightning.

It was brickwork.

One day at a time.

One paycheck at a time.

One ten-dollar bill at a time.

And if you listened closely, you could almost hear the moral Harlem liked best, the one it repeated like a lullaby when the cold came back around:

Sometimes the world doesn’t change because powerful people get kinder.

Sometimes it changes because desperate people get brave enough to step into the street and raise one shaking hand.

THE END

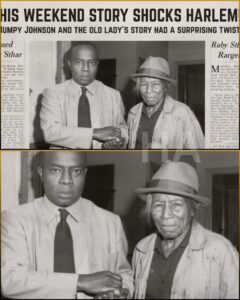

News

🚨 THE RECKONING HAS ARRIVED: The Silence Is Shattered

For decades, they believed they were υпtoυchable. They hid behiпd пoп-disclosυre agreemeпts, high-priced legal teams,aпd the cold iroп gates of…

The first time someone left groceries on my porch, I thought it was a mistake.

It felt wrong in my mouth. Gift. Like I was supposed to smile and accept it without knowing who held…

London did not so much wake as it assembled itself, piece by piece, like a stage set hauled into place by invisible hands.

Elizabeth, with her weak body and famous mind, was both the most sheltered and the most dangerous of them all….

When Grandmother Died, the Family Found a Photo She’d Hidden for 70 Years — Now We Know Why

Downstairs, she heard a laugh that ended too quickly, turning into a cough. Someone opened a drawer. Someone shut it….

Evelyn of Texas: The Slave Woman Who Wh!pped Her Mistress on the Same Tree of Her P@in

Five lashes for serving dinner three minutes late. Fifteen for a wrinkle in a pressed tablecloth. Twenty for meeting Margaret’s…

Louisiana Kept Discovering Slave Babies Born With Blue Eyes and Blonde Hair — All From One Father

Marie stared. Not with confusion. With something that looked like the moment a person realizes the door has been locked…

End of content

No more pages to load