Eirik opened his door and showed Harwick his smoke test. He puffed pipe smoke at the outer planks and watched it bend and escape through invisible seams. He held a feather at the inside log wall and the feather trembled against nothing. “Outer wall takes wind,” Eirik said. “Inner wall sits in still air.”

Harwick asked for numbers. Eirik liked numbers; they listened. He set a ledger. Each morning at six he placed his mercury thermometer at the outer sill and then again at the interior log surface three feet from the stove. He wrote dates and degrees with a steadiness that had nothing to do with pride and everything to do with simple curiosity.

On October nineteenth, with the stove banked to coals, the outer sill read fourteen below. The interior log wall read seven above. Twenty-one degrees’ difference. Harwick could not make that number into a joke. On the twentieth it was similar: minus six outside, plus five inside. Day after day the ledger told the same story—between seventeen and twenty three degrees’ difference, the best morning showing twenty-one. Eirik kept his figures like a man counting favors returned.

The township had to account for its surprise. Martha arrived on the eighth morning with her school thermometer to do what teachers do—measure the world. She took readings at Harwick’s and found pre-dawn lows that made breath fog: minus five to five degrees. Then she came to Eirik’s and found steadiness: plus four to plus ten across the inner surfaces with water pale liquid, with no ice forming where frost had been a regular, hated ring. She recorded it, not out of loyalty but because facts are stubborn things.

When the wind broke again on November third, it came with a hunger that put the earlier storm to shame. Forty mile an hour winds drove temperatures down to thirty-eight below and made indoors a dangerous kingdom. It was in this storm that practical wisdom failed some and saved others. Three cabins in the township were in true peril; the grandfather at the Morrison place had breathing drawn by cold like a bellows; a baby at the Johansson household coughed with the chill in her lungs; a mother at the Johansson place had the kind of fear that burrows into a woman’s voice.

They came to Eirik because fear had no other shelter. Harwick, his wife and two boys, the Morrisons with the failing grandfather, the Johanssons with the coughing infant—they crowded into Eirik’s fourteen by eighteen cabin until eleven people pressed into the warm hush. The musician wind scraped at the outer planks, but inside the inner wall held a lobed calm that insulated human bodies and human tempers. Eirik added extra muslin at his vestibule, shaping an air-lock, and the small demonstration of tobacco smoke at the threshold made the point. Where before the smoke moved a quarter-inch, now it deflected less than an eighth.

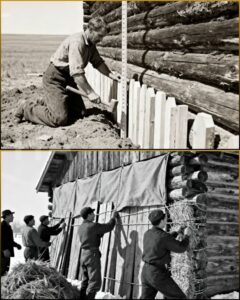

That night the air was mercy. The grandfather’s breathing eased; the baby’s cough softened; the Morrisons stopped burning furniture. Fuel use per person fell by thirty percent compared to their previous consumption. Eirik taught them quickly and without ceremony—lash a temporary plank skin eight to twelve inches off the windward wall, stuff loose straw or hay into the gap, hang blankets inside, and make a vestibule. It was not elegant work. It was desperate and plain as hands. Harwick did the first retrofit on his north wall with bailing wire and rough boards. In forty-eight hours his pre-dawn interior temperature rose twelve to sixteen degrees. That was enough to stop frost where it had been forming every night.

For the rest of that winter the township learned by heat and by habit. Martha kept records for her annual report to the territorial education office, a dry-eyed account that would carry into correspondence and county circulars. Sarah McKenna noted the Johansson baby’s recovery and wrote down dates with the midwife’s precision. Men who had mocked Eirik’s lumber use came to him with measuring tape and practical humility and asked for dimensions and lists of materials. Eirik gave the details without claim—twelve inch cavity, cedar pickets at thirty-six inch spacing, ledger blocks every forty-eight inches, one by tens for the outer skin with one by three battens, half-inch vent slots at the eaves, woven wire at the base, muslin wind-checks up high, hinged shutters for windows. He wrote them into the same ledger he had used during the storm.

There were also costs to learn. The outer skin needed rebattening every few years, because weather works on details. Hay and moss had to be replaced more often than sawdust because of wet seasons; sawdust performed admirably but cost more. Every adaptation revealed a trade-off. But the gains were blunt and easy to see: fuel savings, fewer frost nights, happier babies, fewer funerals. Where once the community measured courage in how much wood a man could burn without complaint, they now quietly measured it in how little wood he needed to keep his family from frost. It was a new kind of sobriety.

Eirik, however, was not merely a man with a ledger. He had come across an ocean with more than tools. In the township he learned to listen. He learned the shape of people as he learned the angle of rafters. Martha admired that he did not brag. Harwick, who had spent years tolerating the plainness of prairie life, learned that there was room for better methods. The Morrisons spoke when they could, and their old grandfather slipped small thanks into his sleep between dreams of roaring wood fires and grandchildren. The Johan family grew less fearful of the biting wind. The town changed in increments.

Spring the following year broke early. The snow melted and revealed tracks and things buried: a barrel lid, a child’s wooden toy, the course of a neighbor’s foot to the barn. In March Harwick arrived at Eirik’s with a notebook that had more questions than blame. “My brother-in-law is homesteading next year,” he said. “Can you put it in writing?”

Eirik made an index of techniques and numbers and passed it along. Martha wrote an account for the county extension bulletin, complete with diagrams. By 1890 the double-wall principle—dead air, sacrificial outer skin, ventilation and baffles—appeared in agricultural extension publications and spread across the plains. Men who had once called him every name came to his door with orders for lumber. They listened as Eirik explained ventialtion and the muslin windcheck; they listened like men who had discovered a recipe and could now replicate it.

If the adoption of Eirik’s method had been merely practical, the community’s gratitude might have remained transactional. But winter had done more than teach them to build; it had put them in each other’s hands. That November—several years after the first storm—a new crisis tested not wood and ingenuity but the softer knot of belonging. A fever swept a neighboring claim; the doctor had to make a ride in a blizzard, and one of the homesteaders lost his lifestock to an unexpected freeze. Folks took turns bringing meals, splitting labor and lending a hand with harvest. Eirik’s cabin became the meetinghouse for simple charity: baking, mending, the giving of warm clothes. He never refused a child who wanted to sit by his fire and listen to the same stories he told about the sea.

Not all stories end with a plaque. Eirik never sought recognition. He was content to have his ledger sit in a drawer and to know that his neighbor’s baby slept throughout the night. But human memory is notoriously fair at imitating law, and the township found ways to honor what could not be easily quantified. On an autumn evening, as the sun bled down the ridge in a thin gutter of orange, the neighbors gathered in front of Eirik’s house. Harwick stood up on a pile of planks and made a short, awkward speech. He said they had called Eirik a fool and that the fool had given them warmth. He said the log of their gratitude could be written small but ought to be written at all.

Eirik accepted a round of handshakes and a cracked wooden bench of praise, which he laughed at more than he deserved. Martha read the ledger’s figures aloud, and children pressed their noses against the outer planks and held hands with elders whose fingers trembled less for being warmed. It was an odd, small ceremony, and later folk would remember it as a turning point—where practical knowledge became a communal legacy.

Years went by and the method spread. Men who adopted it came back with adjustments—some used a wider cavity filled with sawdust, others built masonry sleeves at stove pipes, and the blacksmith offered suggestions about soot and smoke. The schoolhouse in Red Willow had a double wall after the winter that nearly took the township; Martha insisted on it for the children she taught because a warm classroom keeps attention and growing bodies. The county agent who visited wrote a polite formal piece, then a more practical one, then began to recommend double-walled schoolhouses in other precincts. The extension office printed diagrams. Farmers wrote letters across the plains that described in the heat of summer how to trap winter in a wall. The method spread in the economy of necessity and the currency of experience.

Eirik aged as men do—slowly, without drama, with the kind of wear that shows in hands more than in face. He never became a public figure. He remained, in the township, the Norwegian who built a house with a fence around it. Some mornings he walked to the general store and sat in silence with men who once mocked him but now sought his counsel on ventilation for their barns. He taught at harvest-time and in long, patient afternoons how to stuff a cavity so it would not settle. He taught people to hang muslin and to flash tin at the eaves. He taught them to listen to the plain facts of air and heat and to befriend the hidden kindness of stillness.

When he died—quietly, in the bedroom that looked onto the orchard—the town felt a hole the size of a weather hole. They buried him on a small rise near his cabin, under a tree whose roots had not known the threat of frost when he first arrived. Harwick, Martha, Sarah McKenna, and the Johansson mother were there—faces mapped with years of cold and gratitude. The funeral was plain as any frontier gathering: a prayer, a hand-carved headstone, and the passing of recipes for warmth. They read fragments from Eirik’s ledger at the graveside, not out of mummified reverence but to remind themselves of how stubborn gentleness could be.

He left behind the ledger, a bench with a cracked seat, a scatter of tools, and a community that had learned to manufacture warmth from geometry and kindness. But the real inheritance was less tangible: it was a change in how they treated the future. The men who once measured manhood by the size of his fire now measured it by how carefully he prepared for the wind. They sent their children into classrooms where the heat was steadier and the winter lessons less brutal.

At the heart of Eirik’s practice was not mere survival but a kind of humility: to watch, learn, adapt, and to borrow wisdom where it came from the sea and the plains and the hands of a Lakota woman who traded sewn goods and a teacher who kept the ledger of the weather. He had been wrong about some things—no man is wholly right—but mostly he had been right about the stubbornness of air and the patience of careful carpentry.

In time, Red Willow became a place where people took winter less as threat than as a thing to be prepared for. The double wall remained a humble science in the hands of homemakers and barnwrights. Manuals and pamphlets spread the technique in the practical prose of agricultural extension. The Scandinavian methods of packing and ventilation wove into the local vernacular. Every so often a man or woman would bring a child to Eirik’s bench, point out the place where he had written his numbers, and tell the story of the man who built a fence around a house and kept his people from frost.

The story traveled beyond the county lines too. Men who moved westward wrote to friends and families and to county papers and to other lonely posts on the plain. The method was adapted and tested in other towns with other materials. Where straw was abundant, they used it. Where sawdust existed and men had access to mills, they paid the price and enjoyed longer stretches between maintenance. The principle remained the same: moving air steals heat; trapped air holds it. The outer skin takes the weather while the inner stays calm.

There is a kind of quiet heroism in the exchange—an emigrant borrowing from indigenous wisdom, adapting a maritime mechanism for inland cold, and the resulting survival of neighbors who had been too proud to accept help until the cold made their pride pointless. This is perhaps the last and truest lesson of Eirik Olsen’s work: that survival in extremity is often not about who stands tallest in winter but about who is willing to listen, to learn, and to change.

Years later, a school exercise assigned by Martha’s grandchildren asked the students to write about a person in the township who had helped the community. A boy named Thomas wrote about a Norwegian who made a fence for a house and kept a ledger of temperatures. He drew a picture of an outer wall with battens and an inner log house and labelled the muslin windcheck neatly. He said in a sentence that made his teacher grin that Eirik’s house kept the cabin twenty-one degrees warmer than its neighbors in the first storm, and that made his mother sleep better.

Eirik’s ledger sits in the town’s small museum now, behind glass and with the numbers written in a hand that is no longer living. People come to see it on cold days as much for the story as for the artifact. They stand and read his notes and feel the curious mixture of science and gentle stubbornness that it represents. Often they leave to make a pot of tea. They warm their hands and talk about how the world had felt like a furnace and then, because a man measured and wrote and taught, became a little more habitable.

For all the diagrams and circulars and extension publications that followed, the simplest image remains the most moving: eleven people crowded into a small house while storm winds shrieked beyond the outer planks and a single inner wall held warmth like a secret. The grandfather’s breath eased. The baby slept through the night. The mothers who had worried through that year would tell their grandchildren how a fence around a house saved them, and the children would look at Eirik’s bench and scratch the knuckles of their hands where wood had splinters, and someone would laugh and say, “He was stubborn, yes. But look what came of it.”

The final page in the ledger is not remarkable. It holds a figure scratched neatly, then washed by time. But sometimes at dusk, when the wind comes down from the ridge and the plains bend into shadows, the town feels a warmth that is not only from fire. It is a warmth forged in shared knowledge, in borrowed practices made local, in the small, stubborn dignity of preparation. Eirik’s name is maybe not in a book of heroes, but in Red Willow his story is the kind that keeps mothers knitting and men measuring twice and teachers recording the weather. When children ask why they close their shutters tightly and stuff their vestibules with thick blankets each winter, grandparents point toward the old house and say, “Because Tom’s father learned from a Norwegian and a Lakota woman, and we learned not to call each other fools when a better way came along.”

And the wind, which is patient and ever-testing, seems a little less ferocious when a town knows how to meet it.

News

End of content

No more pages to load