We returned to camp to find it empty.

Not messy. Not abandoned in the small chaotic ways that happen when someone goes to the bathroom and forgets to take their thermos. Clean. Gone. The tents were ripped up like someone had hauled them away; the smoldering circle was cold and neat. Chairs stacked. Coolers lifted. The cars? Gone. The tracks in the dust headed away from the clearing into the trees and then—nothing. As if the whole family had been dissolved out of the scene by the careless hand of a god. Only Nova’s backpack lay where she’d left it by the stones, half unzipped and smelling faintly of marshmallow and crayons.

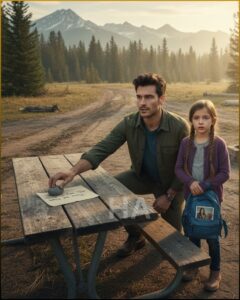

Pinned beneath a river-smoothed rock on the central picnic table was a small note. Lennox’s handwriting: This is for the best. Trust me.

Nova asked, small voice wobbling, “Did they go get help, Daddy?”

I wanted to answer with certainty the way a parent does when a child asks if the monster in the closet is real. “Maybe,” I said. The lie tasted like metal.

The truth—when it refused to stay buried—was sharper. There were tire tracks that headed not toward any road but deeper into the forest and half a plastic hotel key tucked in the dirt with a hotel’s name I recognized from Jackson Hole: a service path, a card, a plan. The forest wasn’t stupid. It would keep secrets like a miser hoards coins. We had to keep moving.

I gathered what we had: Nova’s half-full water bottle, a pocketknife, a lighter, a sweater. They had left us with childlike cruelty—just enough to light a fire, not enough to live on one. That first day we followed the stream. Water means direction. Direction means people or roads or cabins—something that is not the brutal, indifferent wilderness.

Nova was a model of child’s faith. Every step she took trusted me to carry her across the world. She filtered water—no, I taught her to build a charcoal filter and to set a pan on small stones—and she did it solemnly as if the wilderness were a classroom and I had been her teacher all along. At night we slept in a hollow beside the stream, rain pound overhead, and she asked me why our family “would do that.” I had no honest answer.

On the third day a bear came and sniffed the air near our shelter. We climbed a low branch and waited until its breathing slowed and the forest exhaled the animal away. The next morning I found human footprints along the riverbed: deep, angled outward, someone tall with a strange limp. Not my family’s. They were fresh. The trail sometimes vanished, then reappeared as if the person had danced around us in the trees. On the fourth day Nova simmered with fever. I made willow-bark tea in a dented tin cup I’d been saving; I stripped my shirt for a bandage and tied it tight, humming nonsense songs I remembered from Maya’s childhood. That night she slept fitfully and I kept watch, counting the minutes like beads to keep myself from thinking about Lennox’s handwriting.

By the fifth day we found a ranger’s cabin. The door hung open like a tired mouth; inside the air smelled of dust and old wood and the kind of silence that carries weight. The radio was smashed. On the back wall someone had burned a message with a stick—smudged black letters: Don’t trust the one you came with. My skin crawled like a lizard. In a drawer I found a hotel receipt with Sylvia’s neat looping signature—dated the same morning we’d been left. Somewhere in this tangle my family’s excuse of “we had to go” had acquired more purposeful adjectives: planned, rehearsed, cold.

On the sixth day we followed the footprints and the shallower trail and found a red-nylon strap caught on a branch with a first-aid kit inside. The kit was almost new; inside lay a gym card with Lennox’s name and a packet of antibiotics that saved us from a creeping infection in Nova’s ankle. A card from a gym? A hotel receipt? Why would my brother’s name be beside a trail of desperate supplies? The forest was closing into itself like a fist; something else lived among these pines and it had been watching my family for longer than I had known.

Hoarfrost began to lace the grasses on the eighth day. On the ninth, Nova collapsed. I carried her as though gravity were a personal vendetta. Her forehead burned. Her breath came in shallow waves. I whispered to her like prayers I hadn’t thought I believed. “Hold onto me,” I said. “Hold onto me, Nova. Please, love, please.” She drifted on that wavering edge between sleep and sleepless panic; her fingers clenched the back of my shirt like anchors.

We found the second ranger station on the tenth day, shuttered and spray-painted with a desperate note scrawled in soot: Go east. I burned a stack of newspaper and piled wood until I could make a column of smoke brave enough to tell someone the truth. When the helicopter blades finally whined above us and the crew dropped a harness, I felt something like a tide of relief roll through me so hard my knees threatened to break. Nova went up first, limp against the harness, her small body lifted into the humming machine. In the chopper’s cabin they strapped her in, and I watched until they lifted me, too, and the trees slipped away and the world didn’t feel like an abyss any more.

Hospitals smell like disinfectant and the white is almost painful if you’re used to the soft shadows of pine. Nova’s fever broke. A federal agent with a badge that flashed in the fluorescent light told me things I had suspected but didn’t want to see spelled out: there had been a missing ranger months before, notes that hinted at suspicious shipments connected to a corporation registered in Victor’s name, strange payments, and then my family’s filings. They handed me a packet that had once been my life: a fabricated will, forged signatures, a doctored recording of my voice saying things I had never said. They had moved funds within forty-eight hours of my disappearance, siphoning out more than two hundred thousand dollars. They had filed a missing-person report asserting I had walked away, and they had tried to use an edited clip to make me look mentally unwell. Harlo had turned in the manipulated tape.

The agent watched me as I absorbed the bestiary of their betrayal. “They abandoned you deliberately,” he said flatly. “And they attempted to profit off it.”

When they brought me to testify, when they showed the Jackson Hole hotel receipt and the GPS logs that proved Victor’s SUV had taken a service path out of the forest, the first crumble happened. Sylvia’s hand trembled. Lennox’s jaw tightened but then unhinged into excuses like a trick of a flawed clock. Harlo looked like she might vomit.

We didn’t go to court for catharsis. We went because the law is a blunt instrument and the truth had teeth that needed to be set down like stakes. Jared Miles—the ranger whose name I had found scrawled on a torn page in the crevice we sheltered in—had been digging at their transactions. His notes—handwriting experts later confirmed—matched what I found. He’d written about shipments that didn’t line up with logging permits and telephone numbers that led to shell companies. He’d watched men who moved in suits and spoke in hush. He disappeared two months before our trip.

When the prosecution laid out the case, it read like a slow detective novel. The jury leaned forward. There were forgeries, falsified wills, forged fingerprints; there was the altered video showing me declaring my desire to vanish; there were financial records and wire transfers. There were also human things in the evidence: an old scrap of a child’s drawing of three people and a small stick figure under a tree—the kind of thing Nova would do, and an image of a damage deposit receipt where Sylvia’s scrawl suggested she had been in Jackson Hole the morning they left us.

At one point I watched Luna—my daughter, my little comet—stand at the courthouse’s hallway and press her forehead to my leg, trusting me like a ship trusts a lighthouse. The prosecutor asked me to explain what survival had felt like. So I told them: the cold like an accusation; the bear’s breath like thunder; the taste of rain on your own lips when the body is a bag of frayed ropes; the knowledge that a father can carry a child until his own knees fail. I told them about the soot-smeared message—Go east—and about Jared’s page that said simply, If they tell you to trust them, don’t.

The jury returned guilty. Lennox on attempted murder, fraud, endangering a child, falsifying legal documents; Harlo on aiding the cover-up and submitting doctored evidence; Victor guilty of conspiracy and financial manipulation. Sylvia, who had helped but who also broke down on the stand and showed the smallness of human terror, cooperated and received reduced sentencing. The verdict didn’t heal the hollows they left in me. It merely allowed the law to file the fractures into a ledger and close a chapter that had been written in the blood of the missing ranger and the near-death of my daughter.

When it was over, people said things like, “At least you have closure,” as if justice can be a tourniquet against grief. But Julia, my attorney, sat with me on the courthouse steps and let me look at her as if I were not the man who’d been on the edge of breaking. “You did what you needed to,” she said. “You kept her alive.”

After the trial Nova and I moved to Helena, Montana—a small house with a porch that looked at mountains instead of news. Forgiveness did not arrive like a letter in the mail. It arrived slowly, like paint drying over an old stain. Nova started to draw again. She filled page after page with trees and rivers and a man carrying a small child through dark spaces. I started to write—pages about the clearing, the note, the cabin—because sometimes the only way to move forward is to tell the story exactly as it was, even if repeating it hurts.

People would ask me sometimes if I missed them. I didn’t always know what they meant. Which ‘them’—the family that had abandoned us, the family I’d once imagined? There are ways to miss an idea of someone and still know their reality is poison. The truth is this: I missed the version of my father who had told me jokes and shown me how to change a tire. I didn’t miss the man who gambled with my daughter’s life. I grieved both losses.

There were small mercies. Sylvia visited once after sentencing, eyes hollow, voice thinner. She brought with her a crumpled Polaroid of me and Maya at a wedding. “I thought I was saving you,” she said, as if telling the truth were a hygiene act. “I thought if we removed the pain you’d be safer.”

“Safer?” I repeated. “You made us trespass through death for profit.”

“I didn’t know they’d take it that far,” she whispered. It wasn’t an apology; it was more of an admission. The evening she stayed was awkward and full of small, careful pauses. Nova sat at the table and refused to look at Sylvia. When she left, she placed a single folded envelope on the counter—not money, not letters, just a receipt of apology, half-burned by war.

I forgave Sylvia in the only way I could: by stepping out from the exact center of my rage. Forgiveness didn’t mean letting her back into our lives. It meant I would not let her actions shape my soul into something small and bitter. It meant I could walk Nova to school without thinking about the clearing every step of the way.

Months became seasons. The book I wrote did well enough to keep us in that modest house and to buy Nova a second-hand set of watercolor paints. She painted mountains and men carrying children; she painted helicopters and smoky signals. She started to laugh with the sound of someone learning to trust again. Sometimes, when she was sprawled on the floor drawing, she would ask me questions that were heavy for someone her age: “Daddy, was Maya proud of me?” “Do you think Jared ever got lonely?” I answered them as honestly as I could. “Maya was proud,” I would say. “Jared was brave.”

People ask if I wanted revenge. Sometimes, in the swollen seconds before sleep, I did. But revenge is a noisy thing with shallow roots. The law took care of what lay on the surface. What I wanted more than anything was to make sure Nova could sleep without dreams of cold and pine needles. I wanted to teach her that people—even those we trust—are sometimes capable of terrible things but that the world is also full of strangers who show up with harnesses and radios and hands that know how to lift you into life. I wanted Nova to know she had been chosen by love—by me and by Maya—and that that one choice carried more weight than a thousand betrayals.

We eventually started a foundation in Jared Miles’s name. It was small at first: a scholarship for park rangers’ children, money for search-and-rescue teams, and grants for investigations into illegal shipments in public lands. I thought about naming it after Maya, too, because she would have liked the idea of doing good out of that kind of sorrow. We used some of the funds to support families whose loved ones went missing and to train rangers in forensic accounting—an odd niche that had, unfortunately, proved necessary.

One evening, two years after the clearing, Nova drew a picture and slid it across the kitchen table. It was simple: a man with wide, proud shoulders, a child perched on his back, and in the distance a small black helicopter rising above the trees. “Is that me?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said, without hesitation. “You’re always carrying me, Daddy. Even in the pictures you draw.”

“Yeah?” I said, my throat thick with something that wasn’t sorrow. “Even if I’m tired?”

“Especially when you’re tired,” she corrected. Then she added, mischievous as a bird, “And you have better jokes now.”

We both laughed. The sound of it was clean and forgiving.

I still think about them—the ones who left us—that’s unavoidable. But I also think about the people who didn’t leave. The ranger who wrote in soot and whose pages I found; the crew who flew into a wind that smelled like brimstone to bring us out; the nurse who held my daughter’s hand until she slept. There is a weird, stubborn tenderness in the world: while some people will do anything for money, others will risk everything for a stranger. I chose to build my life around the latter.

If you asked me now what survival looked like, I would say it looked like a succession of tiny decisions made every minute: to keep going when the ground was slick; to make a filter out of charcoal and tape; to keep singing stupid songs when the fever made your child’s voice thin; to set smoke into the sky until a rotor heard it. But survival also looked like choosing people who value life as an end in itself over the tidy arithmetic of profit. It looked like courtrooms and verdicts and a book that paid our bills. It looked like a house with a porch that faces mountains and a small girl who paints the things she loves.

On the first anniversary of our rescue, Nova and I hiked to a small bench overlooking a river. There we planted a stone with Jared Miles’s name and the words Watched. Remembered. She placed a bouquet of purple wildflowers on it and then ate a sandwich with jam on both sides of the bread like she always did. As we walked back, her hand folded into mine, I realized that the clearing had become one part of our story but not the only one. The forest had tried to erase us. The people who left had thought they could bury a man and child under their own lies. Instead, a community of strange, brave people pulled us back up, piece by narrow piece.

“Do you ever forgive them, Daddy?” Nova asked that evening as we sat on the porch watching dusk unfurl like blue ink.

I thought of Sylvia’s apology; of the thin, brittle way Victor had looked away in court; of Lennox’s stunted attempts at remorse. Forgiveness, I decided then, is not a single word you hand someone. It’s a road you choose to walk because you prefer the country over the ruins.

“I don’t know if I can forgive all of them,” I said. “But I’m choosing to stop letting them be the center of our story.”

Nova tucked her head under my arm, content like a cat.

“That’s okay,” she said, sleepy. “We get to write the rest.”

We do. I still carry scars—physical ones, yes, but mostly ones that feel like maps: a ridge in my jaw from when a tarp flew during a storm, a small freckle of memory behind my right eye that lights every time I see a hotel key, a tenderness that blesses small things like jam sandwiches. Those marks have become part of the man I am.

The final thing I learned, painfully and plainly, is this: family, in the pure, biological sense, is not the only fabric that binds us. There are other families: the ranger with soot on his hands who warned us by burning wood on a wall; the pilot who flew low in a storm to find a thin column of smoke; the judge who looked at facts and said, “These actions are criminal.” There are hands that pick you up not because they are bound to you by blood but because they are bound to the idea that other people’s lives are sacred.

If this story finds you and you feel alone, or betrayed, or invisible, then please believe this: there are people who will carry you. There are helicopters that will come if you can make a signal. There are courts that will take a long time to render justice, but they’ll listen to the truth if you can lay it out and refuse to be silent. And most of all—if you are someone who has been left—know that you are not the sum of the violent choices others made on your behalf. You are the arc of every small decision to stay, to fight, to feed, to sing.

Nova is ten now in my story’s telling, but in my actual life she has grown, has learned to tell jokes, and can paint with a patience I never expected to see in her. People sometimes stop us on the street and tell her she’s brave. She shrugs and says, “I had a good teacher.” I believe her. She learned from someone who had to carry more than his weight.

Sometimes, late at night, I take Maya’s thermos out from the small cupboard where it lives—clean, dented, waiting—and I think of what could have been. Grief still sits with me like an old, honest friend sometimes. But mostly, the silence that used to feel like an axe now gently empties for a fuller thing: a life rebuilt deliberately, like a bridge over rushing water—not without scars, but strong.

In the end, the family that left us to die in the wilderness regretted it. The law brought them consequence. Life dragged us up and away. We settled in a town where people plant bulbs in the spring and forget their troubles for a while. Nova paints mountains and men carrying children through dark spaces until the figures in her drawings look more like the people we are becoming than the people who hurt us.

I do not think of them with the same heat as I once did. That heat was a fire that nearly consumed me. Now I warm myself with a different fire—the one Nova lights with jam sandwiches and watercolor sets and jokes about moose. It is small and stubborn and good.

If you are here with me now, listening, I want to thank you. Tell me where you are, or say you are listening, and know that your attention is part of this life we stitched back together. If my story helps one person find a faster way out of a dark place, then the ten days in the clearing will mean something more than cruelty. They will mean warning and warning turned into shelter and shelter into a life where the loudest thing is not the echo of abandonment but the steady, ordinary sound of a child laughing.

We learned, the hard way, that the clearest way forward is to build something that cannot be bought—trust, again—out of the treasures leftover after catastrophe. And sometimes, that is enough.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load