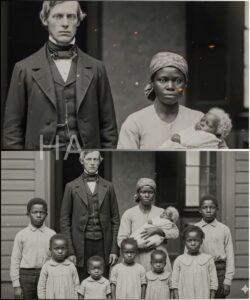

Levine arrived at Bellamal again in the spring of 1841. Madame Duchamp had complained of weakness and dizziness. Levine examined her in the upstairs bedroom while Habert waited below, listening to the creak of floorboards overhead. When the doctor came down, washing his hands carefully at the basin, Habert watched him closely. The pale hair, the blue eyes, the almost gentle smile. It was all there, reflected perfectly in the children whose existence the parish pretended not to see.

“Your wife should rest more,” Levine said to Duchamp, buttoning his coat. “The climate does not favor those of delicate constitution.”

“Of course,” Duchamp replied, relieved to have an explanation that required no action beyond comfort.

Levine turned then, as if noticing Habert for the first time. “Good evening, monsieur. Still keeping everything in order?”

“As best as one can,” Habert said.

Levine smiled. His eyes lingered for a moment, not threatening, not curious, simply measuring. “Indeed,” he said softly, and left.

That night, Habert made a decision he had been postponing for months. If the law would not act, and if the powerful would not listen, then the truth would have to be preserved another way. He began to write a second record, separate even from his private notes. This one was not for authorities. It was for the future.

He wrote names. He wrote dates. He wrote details of where each woman worked, when Levine arrived, how long he stayed. He wrote the words the women would not say, but which lived in the space between their silences. He did not accuse. He did not speculate. He simply recorded, believing that someday, someone would read it with eyes not bound by the laws of 1841.

The eighth child was born in early 1842 at Cypress Bend, a plantation farther north, edging into swampy land where mosquitoes ruled the air. The mother was Elise, barely eighteen, brought into the main house as a runner, sent at all hours to fetch, carry, clean. The baby girl had hair like pale straw and eyes like glass. Elise refused to name her at first, as if delaying attachment might delay the pain that was certain to follow. Her partner ran away two weeks after the birth and was never seen again.

By then, the whispers had grown teeth.

Enslaved people spoke carefully, in fragments, in half-finished sentences shared at night. They did not name Levine. They did not need to. The pattern had become something understood without being said. Mothers warned daughters never to be alone in closed rooms. Midwives watched the road when a doctor’s carriage appeared. Fear settled into the quarters like dampness, unavoidable and always present.

Even among the white population, unease began to surface. Not moral outrage, but discomfort. These children were too visible. Too numerous. They disrupted the fragile fiction that order reigned everywhere it was claimed. Plantation owners began quietly arranging for certain babies to be sold early, shipped to places where their appearance would raise fewer questions. Some were sent north to New Orleans, absorbed into the city’s complicated layers of color and class. Others disappeared downriver, swallowed by distance.

Levine’s practice, however, did not suffer. If anything, it grew. He was discreet. He was skilled. He was, above all, protected by the very structure that made his actions possible. He treated bodies that the law defined as property. Whatever he took from them, the law did not recognize as theft.

The confrontation, when it finally came, was not planned.

It happened in September of 1842, during a fever outbreak that swept through several plantations after a summer of heavy rain. Levine was overwhelmed, moving constantly, sleeping little, riding from house to house. At Bellamal, Marie fell ill. Clare, now five, clung to her mother’s side, frightened and confused. When Levine arrived, Habert was there, standing just outside the cabin as the doctor examined Marie.

“She needs rest and cool water,” Levine said. “The fever has not settled deep yet.”

“And Clare?” Habert asked.

Levine glanced at the child. For the first time, something flickered across his face. Not guilt. Not fear. Recognition. “She will be fine,” he said. “Children are resilient.”

As he stepped outside, Habert followed him.

“Doctor,” he said quietly.

Levine stopped. “Yes?”

“You have seen many children like her.”

Levine met his gaze. The silence stretched. Around them, the plantation moved as it always had, indifferent and efficient. Finally, Levine spoke.

“You are an observant man, Monsieur Habert.”

“So are you.”

A pause. The river murmured somewhere beyond the trees.

“You should be careful,” Levine said. His tone was not threatening. It was instructive. “Observation without power is a dangerous habit.”

“And power without conscience?” Habert asked.

Levine smiled, thin and precise. “Conscience is a luxury afforded by circumstance.”

He turned and walked away, leaving Habert standing with the weight of seven years pressing down on him.

That winter, Habert arranged his affairs quietly. He copied his records again, making two versions. One he sealed in a tin box and buried beneath a cypress at the edge of Bellamal’s land, marking the place only in his memory. The other he placed inside the false bottom of a trunk belonging to a free Black carpenter he trusted, a man who traveled between parishes and occasionally as far as New Orleans. Habert told him only that the papers were important and that they must survive even if he did not.

The ninth child was born in early 1843. The tenth, six months later.

Something began to shift then, not in the law, but in time itself. Abolitionist pamphlets filtered south. Rumors of rebellion flickered like distant lightning. The world that had seemed immovable began, slowly, to crack. Levine sensed it. He reduced his visits. He spoke of plans to travel north, perhaps even return to France for a time. When he left Louisiana in late 1844, there were those who breathed easier, though none dared say why.

No charges were ever brought. No trial was held. Levine lived out his life elsewhere, his reputation intact, his name unmarked by the lives he had altered.

The children grew.

Some were sold. Some died young, claimed by illness and neglect. A few survived long enough to see freedom, their pale faces standing out in newly emancipated communities where identity had to be rebuilt from fragments. They carried questions they could never fully answer. They carried mothers’ silences and a history that refused to fit neatly into any story told aloud.

Vincent Habert did not live to see emancipation. He died in 1859, quietly, of a stroke, his papers still hidden, waiting.

They were found decades later, after the war, after the plantations had fallen into ruin, after new owners dug at the roots of old trees looking for salvage. The tin box emerged first, rusted but intact. The notebook inside smelled of earth and time. It was taken to a parish archive, where a clerk, curious, began to read.

The record did not change the past. It did not bring justice to the dead or heal the women who had learned to survive by silence. But it did something else. It named what had been designed to remain unnamed. It revealed how power had moved unseen, how law had shielded harm, how cruelty could be organized and repeated without consequence.

History, once uncovered, could not be buried again.

And in that small victory, long delayed, there was a measure of humanity reclaimed.

News

The Maid Begged Her to Stop—But What the Millionaire’s Fiancée Did to the Baby Left Everyone Shocked

The day everything shattered began without warning, dressed in the calm disguise of routine. Morning light spilled through the floor-to-ceiling…

In Tears, She Signs the Divorce Papers at Christmas party—Not Knowing She Is the Billionaire’s…..

In Tears, She Signed the Divorce Papers at the Christmas Party — Not Knowing She Was the Billionaire’s Lost Heir…

My Wife Took Everything in the Divorce. She Had No Idea What She Was Really Taking.

My Wife Took Everything in the Divorce. She Had No Idea What She Was Really Taking When my wife finally…

Susannah Turner was eight years old when her family sharecropping debt got so bad that her father had no choice

The Lint That Never Left Her Hair Susannah Turner learned the sound of machines before she learned the sound of…

The Gruesome Case of the Brothers Who Served More Than Soup to Travelers

The autumn wind came early to Boone County in 1867, slipping down the Appalachian ridges like a warning no one…

The Widow’s Sunday Soup for the Miners — The Pot Was Free, but Every Bowl Came with a Macabre …

On the first Sunday of November 1923, the fog came down into Beckley Hollow like a living thing. It slid…

End of content

No more pages to load