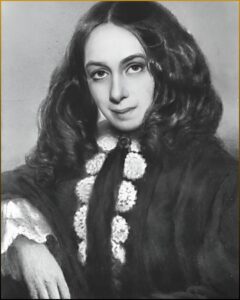

Elizabeth, with her weak body and famous mind, was both the most sheltered and the most dangerous of them all.

She could not run away. Everyone knew it.

But she could think.

And thinking, when a household survives on obedience, is a kind of rebellion that never sleeps.

On an afternoon in the early 1840s, while the fog pressed its face against the windowpanes and the city moved like a rumor, Elizabeth’s maid brought in the post.

It was a small ritual: the maid’s careful knock, her quiet footsteps, the soft placement of envelopes on a tray. Elizabeth watched the tray the way some people watched a horizon. Letters were weather. Letters were fate.

Most were routine: family matters, household logistics, polite notes from people whose lives were made of polite notes.

Then Elizabeth saw a letter whose handwriting did not belong to anyone in the house.

Not her father’s commanding strokes. Not her siblings’ familiar curves. This was bold without being careless, lively without being messy. A hand that did not fear the page.

Her fingers, thin from illness, hovered.

The seal broke with a sound like a tiny door opening.

Inside, the words were simple.

“I love your verses with all my heart.”

The sentence did not flatter her. It recognized her.

It was signed: Robert Browning.

Elizabeth had heard the name, of course. Any poet who paid attention to the living world had heard it. Younger than she was. Bold. Curious. A writer whose poems walked into dark rooms carrying their own light, refusing to apologize for it.

Most men who wrote to Elizabeth wrote as if she were a holy relic. They praised her while building a glass case around her. They admired her suffering more than her mind.

Robert Browning’s letter did not ask her to be fragile.

He wrote to her as if she were an equal.

As if she were alive.

Elizabeth read the letter twice, then a third time, as though the words might change if she stared long enough. She felt, oddly, a tightness in her chest that was not pain.

Flush, her dog, lifted his head from the rug and regarded her with the solemn curiosity of an animal who knew when the air in a room had shifted.

“Flush,” Elizabeth whispered, as if she were letting him in on a secret, “I have been seen.”

That night, after the household had settled into its ordered quiet and her father’s footsteps had ceased in the corridor, Elizabeth wrote back.

Her reply was careful. Not timid, but measured. A poet’s reply: precise, slightly guarded, unwilling to spill her whole self on the first page.

The letter went out.

And then another arrived.

Then another.

One letter became many.

Over twenty months, they exchanged hundreds.

The world, for Elizabeth, changed shape without changing geography. Her room remained the same. The heavy curtains. The faint smell of medicine. The sofa that caught her body like a net.

But now there was a corridor between her and another mind, strung with paper.

Robert wrote about poems, yes, but also about the pulse of the city, about ideas that made the blood lift in the veins. He argued with her gently, then fiercely. He asked questions that assumed she had answers. He did not flinch from her intelligence. He leaned toward it.

Elizabeth found herself waiting for the post like someone waiting for spring.

And then, quietly, he visited.

Not as a spectacle. Not as a conquering hero arriving to rescue an invalid. He came as if he were entering a library, careful of the shelves, respectful of the silence, intensely focused on the book he’d come to read.

He sat near her sofa, not looming over her, not pitying her, his eyes bright with a kind of seriousness that felt like play.

“I always imagined,” he said on their first visit, “that your mind must sound like a room full of bells.”

Elizabeth’s lips twitched.

“And I imagined,” she replied, “that yours must sound like a room full of doors.”

He laughed, delighted. “Doors are more useful.”

“Useful,” she said, “is not the same as beautiful.”

“It can be,” he countered. “If you walk through the right one.”

In those visits, Elizabeth felt herself becoming a person again, not a patient. Her opinions sharpened. Her humor returned, surprising her like an old friend showing up at the wrong address.

Robert spoke to her as if she were not a tragedy.

He treated her as alive.

And being treated as alive does something dangerous to a person who has been preparing to die.

It makes them wonder if death was never the true enemy.

It makes them wonder what else has been killing them.

One evening, after a particularly long visit, Robert stood by the window where the fog had thinned enough to show the outline of the street.

“I can’t stop thinking,” he said, “that this room is too small for you.”

Elizabeth’s stomach tightened.

“It is all I have,” she said, and hated how final her voice sounded.

Robert turned from the window. “No. It’s all they have allowed you.”

The word they landed like a match striking.

“Robert,” she warned quietly, because saying certain truths out loud felt like inviting thunder into the house.

He stepped closer, lowering his voice as if the walls had ears.

“They talk about your illness,” he said. “They speak of your fragility as if it were your nature. But your poems aren’t written by someone who is made of glass. Your poems are written by someone who could split stone.”

Elizabeth looked away. Her eyes burned, not with weakness, but with anger so old it had become familiar.

“You do not understand my father,” she said.

“I understand authority,” Robert replied. “I understand the kind that calls itself love.”

She swallowed. “He will destroy us.”

Robert’s gaze did not flicker. “Then we won’t hand him the hammer.”

Weeks passed. Letters multiplied. Visits continued. Somewhere in those months, without any dramatic announcement, love settled between them like a new element in the air. Not romantic mist. Not sentimental fever. Something sturdier.

A partnership of minds.

A recognition.

And then, because a man like Robert could not live forever inside suggestion, he asked her to marry him.

Elizabeth said no.

She said no because her father would disown her, and disowning in that household was a kind of death. She said no because she was forty and sick and had been told for years that her life was already a fading candle. She said no because she had watched the house swallow her siblings’ futures whole.

“I cannot,” she whispered.

Robert took her hand, careful, as though it were a fragile manuscript.

“You can,” he said.

She shook her head. “You don’t know what you’re asking.”

“I do,” he said. “I’m asking you to live.”

A laugh escaped her, small and sharp. “Live? I can hardly stand.”

Robert’s eyes held hers like a vow.

“You are the strongest person I know,” he said.

Elizabeth felt something in her shift, like a chain loosening by one link.

Strength, she realized, was not only the ability to endure.

Sometimes strength was the willingness to stop enduring the wrong thing.

After Robert left that night, Elizabeth stared at the door for a long time. Flush pressed his warm body against her leg as if he were anchoring her to the world.

In the quiet, she heard the house settling, the old timbers creaking, the whole building breathing in its sleep.

And she thought, with a clarity that frightened her:

If I stay, I will die here.

Not necessarily because of illness.

Because of control.

The next morning, she wrote to Robert.

Her hand trembled. Not from weakness. From the size of what she was about to do.

She did not say yes in a single glowing sentence. She argued with him even as she surrendered. She listed fears, then wrote past them. She was, as always, honest.

But the answer, in the end, was unmistakable.

Yes.

They planned quietly, the way people do when they are planning something that must survive other people’s refusal.

On September 12, 1846, London was the kind of gray that made the world look like it had been sketched in charcoal. The city moved with ordinary purpose. Shops opened. Carriages rolled. People thought about breakfast and errands and debts.

Elizabeth Barrett dressed as if she were going nowhere special.

Her maid, loyal and pale with the secret, helped her with trembling hands. There were no family members. No sisters to fuss over her hair. No brothers to tease. No father to bless.

Only the maid.

And Flush, watching with the anxious seriousness of a creature who understood departure.

Elizabeth’s body protested as she left the house. The air outside felt sharper than she remembered, as if the world had teeth. Her legs were weak. The street seemed too wide.

But Robert was there.

He did not pick her up. He did not carry her like a symbol. He offered his arm as he would to any woman walking beside him.

Elizabeth took it.

They went to St Marylebone Parish Church, not in a triumphant procession, but with the quiet urgency of people who know they are stealing back their own lives.

Inside the church, light fell in pale slabs across the floor. The air smelled faintly of stone and old prayers. It was not grand. It did not need to be.

Elizabeth stood.

Just that was a miracle.

Her lungs worked. Her heart held steady. Her spine, which had spent so long folded into a sofa, aligned itself as if remembering what it had been made for.

The vows were spoken. Simple words that sounded like doors opening.

When the minister pronounced them husband and wife, Elizabeth did not cry. She felt, instead, a deep, strange calm.

Like someone who has been underwater for years and has finally broken the surface.

Afterward, she returned home.

That part was almost more daring than the marriage.

She walked back into the house that had confined her for nearly ten years. She moved through the corridor as if she belonged there, because she still did, technically. She went into her room, sat on the sofa, let the maid remove her bonnet, and resumed her routine.

That evening, she ate dinner with her family as if nothing had happened.

The table was long. The conversation was controlled. Her father sat at the head like a judge presiding over normality. Her siblings spoke in cautious turns, careful not to ignite his temper.

Elizabeth’s hands were steady as she lifted her fork.

Across the table, her father spoke of trivial matters in his deep, satisfied voice. He believed the world was as he had commanded it.

Elizabeth listened. She nodded when required. She smiled when politeness demanded.

Inside her, a ring sat on her finger like a secret pulse.

She was married.

She was no longer merely his.

And he did not know.

There is a particular kind of courage that looks like quiet. It looks like passing bread. It looks like answering questions about the weather while your entire life is turning over like a ship in a storm.

A week later, Elizabeth left for good.

Not in dramatic flight. Not with a shouting confrontation in the doorway. Her departure was quieter than a scandal deserved.

She packed what she could. She took Flush. She took Robert’s hand.

And she walked out of the front door of 50 Wimpole Street.

The house did not collapse. The sky did not split open. The world did not stop.

But something ended.

And something began.

When her father learned the truth, it hit the household like a thrown stone.

He disowned her instantly.

Not with tears. Not with grief. With the cold precision of a man protecting his authority as if it were a holy object.

Elizabeth wrote to him.

Again and again.

Letters that carried love, apology for the pain, explanation, a daughter’s longing for some small mercy.

He rejected every one.

He never spoke her name again.

To him, she no longer existed.

And yet, in another country, she did.

Italy welcomed her with different light. The air felt less like a sentence. Florence opened its arms in a language of warm stone and sun. The streets were alive with voices that did not sound like obedience.

Elizabeth, the woman believed too weak to survive, began to walk again.

At first it was only a few steps, the kind you take while pretending you are not testing yourself. Then more. Then stairs. Then entire rooms. Then streets.

Her body, which had been treated like a doomed thing, responded to freedom like a plant responding to water.

Robert watched her with a fierce, quiet joy that never felt possessive.

“I didn’t save you,” he told her once, when she accused him of it with a tender sort of anger.

“No,” Elizabeth replied. “You did something worse.”

“What?”

“You reminded me I was alive.”

Their marriage was not a fairy tale. It had bills and arguments and tired evenings. It also had laughter, the kind Elizabeth had forgotten she could make. It had mornings where she woke and realized the day belonged to her, not to a household rule.

Her writing surged with energy and clarity.

In the evenings, she wrote with Flush at her feet, the dog’s warmth like a steady endorsement of life. Robert read her drafts the way one reads a powerful document, with attention and respect. He did not eclipse her voice. He supported it, as if her brilliance were not something to compete with but something to protect.

Elizabeth wrote love poems that did not sound like dependence.

Sonnets from the Portuguese rose out of her like music finally given breath, enduring lines shaped from a love that did not erase her but revealed her.

And she wrote boldly about the world beyond her own heart.

Politics. Slavery. Freedom.

She criticized the very plantation wealth her family had depended on, turning her pen toward truths that polite society preferred to keep draped in lace.

It was a kind of defiance her father would have found unforgivable even if she had never married.

In Italy, Elizabeth became more than a survivor. She became a voice, not only for herself, but for the idea that a life can be reclaimed.

And then, at forty-three, she gave birth to a son.

The moment was not neat. It was not effortless. It was real, with fear and pain and breathless gratitude. When she held him, she looked down at the small, wrinkled face and felt something inside her rearrange itself again.

So much of her life had been spent being treated as an ending.

Now she was a beginning.

She wrote of him. She walked with him. She learned the strange miracle of ordinary days: meals, small illnesses, laughter, tantrums, stories. The domestic life she had been forbidden to choose became, in her hands, not a prison but a place of growth.

Fifteen years.

Fifteen years she was never supposed to have.

Sometimes, in quiet moments, Elizabeth would think of her father.

Not with hatred, exactly. Hatred required energy she preferred to spend living. But with a kind of sorrow that did not excuse him.

She would remember him at the head of the table, his voice like a rule, his love like a locked door.

She would remember her own letters, returned unopened, as if her words were poison.

And she would feel, beneath the sorrow, something steadier.

She had left.

She had not died.

The world had not ended.

The true illness, she realized, had never been only in her body. It had been in the air she breathed for years, air made thin by control.

There is a lie households like hers teach their children: that obedience is safety.

Elizabeth learned the truth in Italy.

Obedience is often just another name for disappearing.

In 1861, in Florence, Elizabeth’s life reached its close.

She died at fifty-five.

Not at forty, as London had expected.

Not in the darkened room of Wimpole Street, as her father’s authority had implied would be her only ending.

She died having lived.

Her father had died three years earlier, still unforgiving.

By then, his approval no longer mattered.

That is not a cruel statement. It is a human one.

Approval is not oxygen. You can live without it.

Elizabeth had proven that.

After her death, Robert sat with her papers, her poems, her unfinished thoughts. Grief moved through him like a tide that did not care what he wanted. He missed her voice, her sharp laughter, the way her mind had always seemed to be listening to the world even when the world refused to listen back.

He missed, most of all, her insistence on being herself.

Their son asked questions that no child can ask without breaking something open.

“Where is she now?” the boy whispered.

Robert swallowed. He looked at the room, at the sunlight pooling on the floor, at the pages that still smelled faintly of ink and effort.

“In the work,” he said softly. “In everything she refused to surrender.”

Years later, people would speak of Elizabeth Barrett Browning as if her story were a romantic legend: the sick poet rescued by love, the frail woman carried into sunlight by a bold man.

But that version was too neat, and Elizabeth had never been neat.

The truth was harder, and better.

Love did not rescue her.

Love recognized her.

Love gave her an equal, a companion, a witness.

But the person who stood up at forty, supposedly too weak to live, and walked straight into her own life was Elizabeth herself.

She walked out the door.

She chose freedom over permission.

She chose the terrifying responsibility of her own future over the familiar comfort of someone else’s control.

Sometimes survival means leaving.

Sometimes courage looks like a woman rising from a sofa the world thought would be her coffin and placing her feet on the ground as if she had always belonged to it.

And if you listen closely, even now, to the pages she left behind, you can hear the sound that truly changed her life.

Not the sound of a romantic vow.

The sound of a door opening.

The sound of a person choosing to exist.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

March 6, 1806 – June 29, 1861

Poet. Rebel. Survivor.

She did not need saving.

She needed freedom.

And she took it.

News

When Grandmother Died, the Family Found a Photo She’d Hidden for 70 Years — Now We Know Why

Downstairs, she heard a laugh that ended too quickly, turning into a cough. Someone opened a drawer. Someone shut it….

Evelyn of Texas: The Slave Woman Who Wh!pped Her Mistress on the Same Tree of Her P@in

Five lashes for serving dinner three minutes late. Fifteen for a wrinkle in a pressed tablecloth. Twenty for meeting Margaret’s…

Louisiana Kept Discovering Slave Babies Born With Blue Eyes and Blonde Hair — All From One Father

Marie stared. Not with confusion. With something that looked like the moment a person realizes the door has been locked…

Dutch Schultz SENT 12 Men to K!ll Bumpy Johnson— Only ONE Walked Out (And He Delivered THIS Message)

The message was simple: Work with Dutch. Pay tribute. Or get buried. Madame St. Clare listened without blinking. When the…

Malcolm X’s K!ller Had 30 Seconds to ESCAPE — Bumpy Johnson Made Sure He NEVER Made It to the Door

He looked back at Malcolm. Malcolm understood everything in a blink. The gun. The angle. The child. The impossible arithmetic…

She Could Not Afford a Birthday Cake Yet One Small Act of Kindness Changed Everything for Her Son

“Happy birthday, Bear,” I said. That was my nickname for him since he was a toddler, because he used to…

End of content

No more pages to load