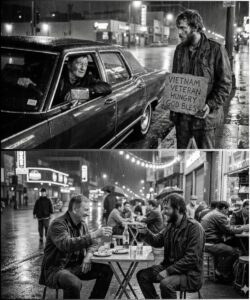

So when a black Lincoln rolled up and the window came down, and the man inside said, simply, “When did you serve, son?” Jerry thought at first it was a trick of tiredness. He expected an insult, or a thrown paper cup, or a television face that belonged to another life. Then he heard the low baritone, the slow cadence of a voice that belonged to a different, almost mythic America. “Two tours, sir,” he managed. “Sixty-eight to seventy.”

John Wayne glanced into the rain-lashed face and saw a young man—thin, eyes rimmed with a kind of exhaustion that was deeper than hunger, a man who smelled of city gutters and trench cold. He thought of the men who had come home from the wars he had not fought. He had been unable to join the military in his youth—medical deferments, family obligations, and a life that already held small sacrifices. For a man with the silhouette of a cowboy, the absence of a uniform had become a private ache. He had compensated by honoring, in his way, those who had worn it. That night, at that green light, he folded his hands around the wheel and did a thing he had not planned at all: he told the young man to get in.

Jerry hesitated—nervous, suspicious, ashamed of the wet smell he carried with him and the filth under his nails. This was Los Angeles in 1972; it was a city of harsh faces and harder itineraries. Men with money often waved disdain like a flag. But John Wayne’s voice did not carry the contempt Jerry had grown to expect. “I don’t want to mess up your car,” Jerry said, because that was a small human rule he had learned on the street: don’t inconvenience those who are already kind enough to look your way.

Wayne leaned in, the cigarette less an indulgence than a memory, and answered as plainly as someone who had lived too long to bother with false courtesies. “I don’t care about the car, son. Get in.”

The warmth inside the Lincoln was like another climate. Jerry’s teeth had been chattering hours earlier; they stopped. The heater breathed, and with it came a quiet that allowed him to feel his hands without the tremor of cold. They drove without much talk. Rain on a car roof is a kind of private percussion, and then Wayne asked, casually, “When did you last eat?”

“A little bread this morning,” Jerry said. It felt like announcing a crime.

They parked at a motel that smelled like carpet cleaner and the notion of shelter. Wayne paid for two weeks, enough so the room would not be a revolving door of homelessness. He handed Jerry five hundred dollars in cash and a business card with a name scrawled on the back: Tom Mitchell, VA counselor. “Tell him Duke sent you,” Wayne said. “He’ll help.”

Jerry didn’t have words then. His throat was a valley of something he could not name. He fumbled with the money as if afraid to contaminate it with his gratitude. He tried to offer something that would balance the ledger of the moment: promises that he would call, that he would not waste the chance. Wayne waved him off. “Don’t thank me,” he said. “Get your life back on track. That’s all I’m asking.”

The man walked away into rain, a figure who had given something seismic but not seeking seismic praise. John Wayne closed the motel door behind him and walked into the night with the rain striking his shoulders and the small satisfaction of having done what felt right settling around him like an armor.

Inside the motel room, Jerry soaked in hot water until the world loosened like a fist. He shaved the beard that had been more cloak than fashion. He did not look at himself for a long while. When he did, the boy he had been and the man he had become argued in the mirror. He called the number on the back of the card the next morning, hardly believing that a name written in a hurried hand could unlock anything at all.

Tom Mitchell was real, perhaps larger in compassion than his title implied. He believed something of what Wayne had said because Wayne’s name was not easy to use without consequence; “Duke” carried weight. Mitchell’s voice slid into matter-of-fact protocol—first intake, paperwork, an appointment, what services were available. There were beds, there were counselors specialized in combat trauma, there were people who had survived similar thinness and could, in time, become maps that Jerry might navigate.

The first months were halting. Recovery is not a straight line. There were slips—rum that smelled like old comrades, nights when nightmares demanded a toll—and there were triumphs: a program that helped him not only in therapy but in practical training, an introduction to a man who taught plumbing because he needed help and because the job had a rhythm that made sense to hands used to heavy things. The work steadied him. It put a weight in his days that belonged to something other than survival: responsibility, pride, a measureable competence. Wayne had given money and access, but the rest—Jerry’s slow hard work, the people who took him in, the counselors—built the scaffolding of his life.

Years passed. Jerry dried into someone else, not less haunted, but more domesticated by routine, laughter, and small victories. He married a woman from the neighborhood who had a laugh like a bell and a patience like a bridge. He named his plumbing business Duke’s Plumbing, partly as homage, partly as a talisman: a reminder of a night when an actor who was also a man had altered the course of his life.

He rarely pressed Wayne’s number again. That was not the point. Wayne had done what he did quietly. Those were the acts that made a life more than a legend. He kept the business card, folded and delicate, inside his wallet for decades. It was proof, an artifact of a kindness that had not asked the world to witness it.

Word spreads in the way it does when a life has a center and people lean in. In 1995 a Los Angeles Times reporter working on a piece about homeless veterans called Jerry. The story wanted a human who could stand in as both witness and emblem of what years of civic indifference had cost. Jerry told the story, slowly, like someone admonishing himself to remember all the small mercies. He produced the card—yellowed, ink faded from the constant opening and closing of a wallet—handwriting that matched the calloused logic of the man who had given it to him. The reporter’s eyebrows rose. The story ran with a photo of Jerry in front of his shop, the Duke silhouette a logo on the truck behind him.

After the piece, other veterans called with similar stories—anonymous cabs with cash, a quiet phone call that changed things, checks that arrived on the door of a rehab center. None of those men had been asked to go public. None had expected their acts to knit into a broad portrait of a man who had given large favours in small packages. But they did. Wayne’s estate, when it later reached out privately to some men, confirmed a pattern of private giving.

For Jerry, the trajectory turned in ways that felt almost like seeing the world through binoculars that had shifted focus. He found purpose in providing the help he had been given. He used his own money to start Second Chances for Veterans, a small nonprofit that focused on housing and job training for older veterans who had slid into homelessness. It was not a grand charity with celebrity fundraising galas. It was a small, stubborn place, one that learned how to navigate bureaucracy and to negotiate the tiny kindnesses that aggregated into major life changes: a plumber here, a caseworker there, a roof fixed, a bed that did not leak.

He told his children the story often, sometimes at breakfast, sometimes before they played outside. They learned to revere small, practical acts in the way that certain families honor osteoporosis of tradition. “You never know what a turn can do,” he would say. “You never know which corner will be the place that decides everything. But you keep going.”

If the story is about a star and a soldier, it is also about the ways the country treated its returned fighters. The nation that had sent its sons overseas often shrugged its shoulders when those sons returned different. It forgot how to measure the costs of war in other currencies: in insomnia, in the twinge of a hand that could not forget, in the small humiliations of being a man who had killed in an unlovely cause and then found himself refused employment for that very truth.

John Wayne carried his own complex about service. He had not worn the uniform in war—circumstance, family obligations, and health had intervened—but he had the cultural muscle of patriotism and a private conscience that fed on the emptiness he sometimes felt at his own compromises. He made amends by tending, quietly, to those who had borne the brunt of his absence. The acts were not public because Wayne had learned early in his fame that good deeds shouted often become shadows in the newspapers the next day, and that the truth of a kindness is sometimes in its anonymity.

Then there were the small and persistent echoes that made Memphis of the mind. Men who had been given checks would find ways to pay it forward. The ripple effect was not quantifiable except in stories, in lives that changed, in a man who had the same hands he had always had but used them differently than he used swords in plays and films. Wayne’s public persona—stoic, iconic, carved from the grain of a bygone American myth—was complicated by the way he lived privately. People tend to prefer their legends unshaken. But the truth was more precise: he was a man who had decided to be prosaically kind.

Time passed, as it always does. Jerry’s plumbing business thrived and then plateaued. His nonprofit grew by degrees. He married and lost, and then remarried; life experimented with him in the quiet ways life does. He watched the world change: Nixon resigned, the country argued and raged, music altered the grammar of evenings, televisions became more common, and the faces on them changed more often. He collected both joy and sorrow with the same hands that had once gripped a rifle in a jungle and then fumbled with a ratchet in a basement under a sink.

He wrote Wayne a handful of letters over the years, letters that never expected answers. “Thank you,” they said, which is a lifetime’s work, not a request. He called Wayne’s number once in the first year to leave a message of thanks. “Duke,” he left on the answering machine, because gratitude sometimes has the cadence of familiarity, “I’m doing fine. Thanks to you. I started a small shop. Thought I’d let you know.” He got no response, not because his words went unread but because Wayne had not sought public commendation. The silence did not feel like a slight.

In the middle of a life that was, materially and spiritually, reasonably whole, Jerry experienced one of the most human tragedies: the realization that even gratitude has limits in the face of mortality. When Wayne died in June 1979, there was a short, honest grief. For Jerry, it was not about losing a Hollywood icon. It was losing a man who had stepped off the set of his life long enough to do a small, decisive thing. Wayne had given a life back.

So Jerry went to the funeral not as a celebrity pilgrim but as a man who owed another man a quiet debt. He stood with other veterans at the edge of the procession, a small placard with his own name on a ribbon pinned to his jacket. He did not speak at the funeral. He did not expect the world to understand the ledger of favors. He simply stood with his hands folded, the way he had once been taught to stand at attention, and let the rain—if there were rain that day—wash over the differences between his life and the one Wayne had lived.

There is a remarkable thing about small acts: they often plant the seeds for larger ones in people who have been spared from the brink. Jerry had been three days away from an ending that would have rewritten what followed; he had been at the end of his tether when someone decided that human being matters more than convenience. This is the kernel that became Second Chances for Veterans. He used the principles Wayne had given in his own way: anonymity when necessary, dignity first, the practical path to a new life.

With the nonprofit, Jerry learned the slow art of bureaucracy. He wrote letters to agencies, begged for small grants, made partnerships with laundromats and pizza shops that would donate a meal and a warm place. He became an expert at locating what a man needed besides a bed: documentation, a VA caseworker who would vouch for his service, a counselor who would be patient with the jagged rhythms of PTSD. Every person fetched from the street was a renewed chance to remake the world in the small way he had been remade.

He named the plumbing business Duke’s in a way that surprised some clients but pleased most. People liked the story of a man saved by a movie star. It had the architecture of myth and the bones of a true thing. Jerry’s children grew up hearing the story at breakfast and repeated it at sleepovers. It was a parable that required no sermon: turn the car around.

The heart of the story is not Wayne’s fame but the choice each of us makes when we encounter someone who needs help. The green light that night had been a signal of something ordinary—go, proceed—but Wayne chose to stop. It takes a particular kind of bravery to reverse direction in a culture that vectors forward. To go back to a corner, to invite someone into warmth despite the smell and the tears, to pay without spectacle—that is not small courage. It is the quiet labor of humane men and women.

Jerry kept that business card for twenty-three years before framing it. He had used it as talisman and proof, and then as his own compass. When he finally framed it, he wrote beneath it a small plaque: He turned around. December 1972. Thank you, Duke. The frame hung in his office above the phone, under a small photograph of a night on the corner taken years later by a man who had become a friend and wanted to capture the geometry of that life-shift. Visitors asked about it, and Jerry told them the story, slow and careful, as if he were counting syllables so as not to lose the weight of each one.

When the nonprofit matured, Jerry brought it into a space with a small office and a few beds. He took calls from men who had nowhere else to go. Sometimes he recognized them from twenty years earlier. Sometimes they were young and raw and needed only a place to breathe before therapy could begin. He taught a man to thread a sink trap and another to read a meter. He taught kids the dignity of work. He ran fundraisers that were awkward, local, and sustained. The city supported him in small ways. People donated. The men who had been helped came back to volunteer. It was exactly the sort of thing that multiplied quietly.

In 2010, after decades leaning into the work, he opened a program he called “The Turnaround,” a training initiative that taught trades—plumbing, carpentry, electrical work—so veterans could be employable and have meaningful, paid labor. He named a scholarship after the man who had given him those first steps. It was not a grand monument; it was a concrete resource measured in vocational certificates and the number of beds not rented by despair but filled by hope.

There are scenes in life that build to a high tension not because of external thunder but because of an internal heat that demands release. For Jerry, the most dangerous moments were nights alone before the Lincoln had reversed, before the money, before the counselor’s patient voice. Those nights were small tragedies in miniature—heaping shame, hunger, and the heavy, quiet knowledge that no one was coming to save him. The decision to save—or not—your own life is a private courtroom, and the judge often has no mercy.

When the press finally picked up his story in the ’90s, when his life became one of many testimonials about forgotten veterans, Jerry was surprised by the ripple. People wrote letters to him, asked him to appear on radio programs, called with offers to help. Some people wanted to make monuments. He always refused the bigger spectacles. Wayne had not wanted a monument. He had wanted real help. Jerry tried to obey the shape of that wish by being discreet, fiercely effective, and careful not to let gratitude become a trumpet that drowned the point.

The climax of Jerry’s story is both the turn of a car and an accumulation of small acts that become unstoppable. It is not the climax of fireworks and speeches; it’s quieter. It is a man who decides not to die because a stranger takes him in. Later the man decides to walk into another stranger’s life and do for him what was done for him. That is the kind of high point that changes generations.

There is an important recognition in these stories: many of the people Wayne helped did not go on to write books or even to become prominent. They lived, they worked, they raised children. Their quiet returns to life fed communities. Jerry’s story was emblematic because it had the full arc: near-death, rescue, rebuilding, and then the replication of mercy. That is the thing that makes meaning out of an isolated act. It is the way kindness loops back into society.

Years later, when Jerry stood in front of a group of new recruits at his training center, he would sometimes ask them to sit in a circle and tell their stories. He thought narrative was a kind of therapy. People needed witness. He would tell them his story and then ask a question that felt simple and yet enormous: “Who turned their car around for you?” The answers varied. Some had a church that fed them. Some had a neighbor. Some had a social worker who refused to write them off. The point was not to make Wayne a lone hero but to make them see that anyone could be the person who turned around.

“You don’t need a celebrity or a legend,” he would tell them. “The person who turns around could be you. Or it could be a kid with a pickup. Or it could be a social worker who stays late. The important thing is that we don’t think someone else will always do it.”

That logic formed the beating heart of Second Chances: that ordinary people could intersect with one another and produce extraordinary outcomes. That evening in December, Wayne had been one of those ordinances, but he had not been unique in the sense of being alone. The world is better when we look for the person who needs help and choose to act.

There were complications in the years—politics, funding disputes, people who felt insulted by offers of help, the stubborn headaches of a nonprofit. People think transformation is neat; it rarely is. There were nights when Jerry went home exhausted and frustrated, curling into the small happiness of a warm bed and an argument with dinner that needed less salt. He had fights with his children, disappointments with employees, days of boredom that made him fret. But underneath everything steadied a current: the knowledge that something mattered deeply.

When his grandson bounded into the workshop one afternoon and picked up a wrench, Jerry taught him how to tighten a pipe without overwrenching it. He found himself laughing at jokes he would have once considered unfit for a man whose stoicism was part of his charm. He read little poems at night sometimes, under his breath, about small mercies. He had been a soldier, then a salvaged man, then a builder of other salvageings. He had been tended by a celebrity who had the decency to be profoundly human.

It is fitting that the end of Jerry’s life was quiet, not theatrical. He died at home in the presence of family at the age of seventy-six. His hand was in his wife’s. He had told her the story of John Wayne a hundred times, and she knew it by heart. She had not been there the night in the rain—she had not known him then—but she had cherished the phone call that led to their life together.

At his funeral, men from across the city came—some of them had been clients, some had been colleagues. Veterans in neat suits stood beside plumbers in work shirts. A framed copy of the business card hung above his casket, under a small plaque that read simply: He turned around. December 1972. Thank you, Duke. A small band played something that sounded like a cross between hymnal and march. People told stories. They laughed. They cried. The arc of one life, compensated by the kindness of another, held together.

What is a humane ending? It is not tidy. It is not an apology that makes the world suddenly perfect. It is an acknowledgment that people can be both complicated and capable of goodness. The humane ending of this story is not that Wayne’s giving solved all the problems of veterans. It did not. It is that one small act cascaded into something bigger: a man’s choice to be alive, a family formed, a nonprofit that served hundreds, plumbers trained, roofs repaired, lives gently redirected.

In the years after Wayne’s death, Jerry sometimes wished for a last conversation with the man who had made his life possible. He imagined telling him about the nonprofit, about the men it had helped, about the children who slept easier because someone had chosen to take a detour. He imagined Wayne, with a cigarette behind his ear, grinning and telling him modestly that it had been nothing—a woman’s equivalent of a shrug. But of course Wayne was gone. The imagined conversation lived then in lighter places: in the faces of the men who had been given a chance, in the kids who learned trades, in the small offices that found their lamps full. The gratitude found its own lodging.

When people asked Jerry if he had ever regretted anything, he would pause and then say, simply, “I regret not turning my car around sooner for others. I didn’t always see what needed seeing. But when I did, I turned. And we kept turning.”

If there is a lesson to be had here, it is not a moralizing one but plain and practical. Try to recognize the man at the corner. If the green light is a signal to proceed, sometimes let it be an opportunity to stop. Human lives are not transactions. They are accumulations of small decisions. To change the course of a life, all it usually takes is a willful, inconvenient kindness. The rest is work.

John Wayne, the actor who had played many rough, honorable men, had become, in the small ledger of a single corner, one such man not on camera but in life. He had driven past and then driven back. That U-turn saved one life that night and helped produce the ripple that saved hundreds more. Jerry’s life, which could have ended under a bridge, instead repaired pipes, built houses, taught trades, and anchored a nonprofit. It was a chain of kindnesses that began at a green light and a rain-smeared cardboard sign.

On the wall of the nonprofit, under the framed business card, Jerry had the words of his own making: “We are what we do for each other. Remember. Turn.” The phrase was not a slogan. It was a complicity in hope.

In the end, perhaps, the most truthful tribute to John Wayne is not to raise statues or to crown him anew, but to continue the labor he practiced in private: to be someone who can turn in traffic not because it’s dramatic, not because there’s an audience, but because the act itself is the only fitting tribute to the humanity we owe one another. The rain will fall. The city will forget. But some nights, if you are lucky, a car will stop, and a warm seat will wait, and the world will be remade—quietly, by the simple decision to go back.

News

🚨 “Manhattan Power Circles in Shock: Robert De Niro Just Took a Flamethrower to America’s Tech Royalty — Then Stunned the Gala With One Move No Billionaire Saw Coming” 💥🎬

BREAKING: Robert De Niro TORCHES America’s Tech Titans — Then Drops an $8 MILLION Bombshell A glittering Manhattan night, a…

“America’s Dad” SNAPPS — Tom Hanks SLAMS DOWN 10 PIECES OF EVIDENCE, READS 36 NAMES LIVE ON SNL AND STUNS THE NATION

SHOCKWAVES: Unseen Faces, Unspoken Truths – The Tom Hanks Intervention and the Grid of 36 That Has America Reeling EXCLUSIVE…

🚨 “TV Mayhem STOPS COLD: Kid Rock Turns a Shouting Match Into the Most Savage On-Air Reality Check of the Year” 🎤🔥

“ENOUGH, LADIES!” — The Moment a Rock Legend Silenced the Chaos The lights blazed, the cameras rolled, and the talk…

🚨 “CNN IN SHOCK: Terence Crawford Just Ignited the Most Brutal On-Air Reality Check of the Year — and He Didn’t Even Raise His Voice.” 🔥

BOXING LEGEND TERENCE CRAWFORD “SNAPPED” ON LIVE CNN: “IF YOU HAD ANY HONOR — YOU WOULD FACE THE TRUTH.” “IF…

🚨 “The Silence Breaks: Netflix Just Detonated a Cultural Earthquake With Its Most Dangerous Series Yet — and the Power Elite Are Scrambling to Contain It.” 🔥

“Into the Shadows: Netflix’s Dramatized Series Exposes the Hidden World Behind the Virginia Giuffre Case” Netflix’s New Series Breaks the…

🚨 “Media Earthquake: Maddow, Colbert, and Joy Reid Just Cut Loose From Corporate News — And Their Dawn ‘UNFILTERED’ Broadcast Has Executives in Full-Blown Panic” ⚡

It began in a moment so quiet, so unexpected, that the media world would later struggle to believe it hadn’t…

End of content

No more pages to load