“How can they be so… ordinary?” Chio asked one night, speaking under her breath in their narrow dormitory. She was the youngest of the group, barely twenty, and fear and curiosity warred in the pupil of her eye. “They have songs, husbands, children. They laugh.”

“They bombed our cities,” May said quietly, her voice brittle like thin ice. “They killed our boys.”

“They treat us as human beings,” Fumiko said, the syllables of her voice rounded by a faith for which she had always taken refuge. She had been given a Bible by the camp chaplain, and the possibility that Christianity might be real in the mouths of strangers began to tilt something in her. “It’s different here. It is not cruelty.”

The women divided themselves—without banner or formal decree—into camps. Silito anchored the traditionalists: keep Japanese customs, bow to the emperor in private, hold tight to the script that had formed them. The pragmatists kept their heads down, learned enough English to function, hoarded their thoughts like discreet coin. Others—Chio, Fumiko, sometimes young Hatsuko—tilted toward questions that tasted like treason and truth.

Small, human acts accelerated the unravelling. The American cooks sometimes learned how to make a crude rice dish when they noticed the Japanese nurses picking at unfamiliar vegetables. An American named Helen who had learned a few Japanese phrases bent down to help Hatsuko pick up a bundle of linen and smiled in a way that made Hatsuko laugh. “Daijōbu,” she said, and their laughter, brief and astonished, was a translation that needed no other words.

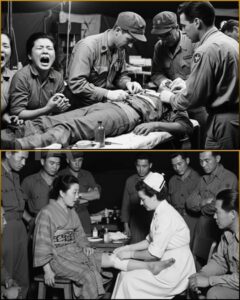

Months into their stay, Yuko found herself assigned to the camp hospital. The hands of the American nurses were skilled; their language curt and efficient. One morning a reel of film was shown in the recreation hall. The lights dimmed and images flickered—American field hospitals with nurses and doctors bent over Japanese soldiers, foreign faces set in concentration as if the man beneath their hands were their own. They watched operations, transfusions, the horrors of battle and then the clinical insistence on life.

The room was silent when the lights came on.

“This cannot be real,” someone whispered, but they all knew the images had been shot from military ships and hospital tents. The moral terrain the government had sold them—that surrender meant certain shame and that Americans would treat them as less than human—began to crumble into shards.

Then, on a cold March morning, everything they had managed to hold as a cohesive identity shattered in a single operating room.

The patient was a captain, captured in the Philippines after he had tried to resist. He had survived, but barely—an attempt at suicide, a blade that had not completed its task. Blood pooled in the surgical field; saline laced the air with a smell Yuko recognized from her past shifts. American doctors worked with the unremarkable, terrifying precision of men and women who had held life at their hands for years. A surgeon barked for instruments. A nurse handed them. A doctor asked for a sponge. Yuko stood at the doorway, the operating room light haloing the figures in blue, and for an instant she could not move.

“Nurse,” the head surgeon said, looking up at her with eyes like flint. “We need another pair of hands. Will you assist?”

There was no time for thought—there never had been—only reflex and training. She scrubbed in and took a position at the table. Her fingers moved between clamps and sutures, between the same sterile light and the same humming machines that had once been her world. The captain’s blood had salted her gloves; she smelled him and felt, absurdly, ashamed. The knot of ideology and grief that had held her together loosened into a runny, dangerous empathy. She set aside the thought of honor; she set aside the story of what a Japanese soldier must be. She stitched veins, helped administer transfusions, passed the necessary instruments with the efficiency of a professional.

They saved him.

At the end, the surgeon removed his mask and nodded. “Thank you,” he said, in plain English. “You were excellent.”

“Arigatō,” Yuko breathed, voice tiny. The word felt both like an admission and a betrayal.

Back in the dormitory, she undressed in a slow, forced ritual. Fumiko watched her and asked, quietly, “What was it like?”

“You should not ask me,” Yuko said. “I have broken something.”

“No,” Fumiko contradicted softly. “You saved a life. That is not breaking.”

But something had broken. Not Yuko, not entirely, but an internal map with the emperor’s face scrawled across every mountain and river. The operating room had been a crucible; the surgeon’s eyes had been the forge. What they did to that captain—what they did to any man—rendered the propaganda into meaningless noise. To watch enemy hands pull a soldier back from death was to see, in the most visceral way possible, that the enemy saw life as sacred.

The debate in the barracks that night turned vicious and luminous at once. Silito cried out that they were being turned into agents of the enemy, that the Americans treated them well only to pacify them and use them as propaganda. “They feed us!” she shouted. “They give us beds! They do not want our hearts; they want our tongues!”

“But they did not let him die to humiliate him,” May said. “They connived nothing. They acted because he was human.”

“You were trained to never accept surrender,” Chio said to Yuko, voice raw. “We believed—if they took us, it was worse than death. How can you stand knowing we were lied to?”

“What else was a lie?” Yuko answered, and the question expanded into every corner of the room.

Months stretched like the cold prairie winter. Letters arrived from home, censored but enough to tell the story of ruin. The nurses received news of burned cities and starving children, and a guilt heavy as iron settled into their ribs. They had eaten and slept and been tended to while home became an abstract agony.

One letter arrived for Aiko. Her mother wrote in a trembling hand about a house that was only a memory and how neighbors said their son had died heroically. Aiko folded the letter and tucked it away and did what many did—smiled politely in public and sobbed in private.

“Will my father speak to me when I return?” she asked Fumiko one night, fingers fumbling the locket.

“You were a nurse,” Fumiko said. “You did what you could to keep people alive.”

“But they will say I was with the enemy,” Aiko whispered.

Repatriation became an ever-present fear. If being captured carried the stigma of betrayal at home, then those who had known ordinary hospitality from the enemy feared returning like criminals going home.

The end of the war came like a sudden, terrible weather. Emperor Hirohito’s recorded voice, the one that many had never heard, spoke surrender into the radio and reality reoriented itself with a nauseating, vertiginous finality. They gathered around the camp radio with guards who hugged each other awkwardly, not sure whether to mourn for the dead or the lost illusions. Tears blurred the words; silence held a new kind of meaning.

It was not until spring of 1946 that they boarded a transport ship to return to Japan. They left Fort Lincoln with sturdier frames and minds that had been forced into new shapes. Yuko gathered the others before they disembarked in Seattle and said, quietly, “Remember that what we saw was real. Remember that mercy is not a weapon.”

There was no cheering when they left. The ship’s hull thrummed with the muted conversations of women who had been through too much to be sentimental. The return to Japan was a confrontation. Yokohama was a skeleton of its former self—pier once proud reduced to a ruinous, ash-scented shore. Americans in uniform directed traffic with the brisk efficiency the nurses now recognized. Children in ragged clothes lined the docks like small ghosts, and Yuko felt a hot, sharp shame that they had eaten well while others starved.

Homecomings cut and cold. Mothers hugged daughters but left out questions and then gave them back small, suspicious smiles. Some families refused to speak about their time in enemy hands. For others the years of occupation complicated things further—some married, some adopted American modes of medicine, some kept their experience hidden like contraband.

Yuko returned to a Tokyo that had been gutted by firebombs and political certainties. Her father’s house was rubble; her father had not survived. Her mother, diminished by grief, looked at Yuko with a mixture of relief and accusation.

“You survived?” her mother asked, and the question had the weight of a verdict.

“I was treated fairly,” Yuko said. She left out the more dangerous truth: that she had seen the enemy’s hands tending their own, the way a boy once taught to hate an old man for his accent might later find himself learning to listen.

“In our papers,” her mother whispered, “they called some prisoners pitiful.” The word hung small and brittle in the kitchen. “Did they force you to speak…”

“No,” Yuko said. “They allowed us what was due to human beings.”

This answer satisfied none and explained everything. In the quiet that followed she began to pull from her memories and the small, abiding habits she had learnt—clean techniques, better bandaging, the gentle way an American surgeon held a patient’s life like a thing sacred. She found work in a hospital because that was how she had learned to breathe. Years later, she would sit behind a desk as the director of nursing at a major Tokyo hospital and wonder at the strange arc of a life shaped by compassion from the other side.

Some of the other nurses fared differently. Chio married an American medical student who remained in Japan after the occupation and was disowned by her family for a time. Fumiko built a modest mission clinic in Hokkaido and said often that what the American chaplain had shown her had been the truest form of Christianity she had ever seen. Hatsuko eventually wrote a small manual of wound care for nurses in provincial hospitals, borrowing techniques she had observed in the camp. Three among them could not reconcile what they had seen with what they had been taught, and the psychic rupture was too much; they took their own lives. These tragedies collected into an ache that never vanished.

In 1975, thirty years after the moment the operating room light had cut through Yuko’s certainty, eleven of the original twenty-seven reconvened in Kyoto. The city smelled of new businesses and the old rice-stall hums, but the women who met were both older and younger than their years—older for the time that lay between their capture and reunion, younger in the secret places that tenderness had forced open inside them.

They sat around a low table and spoke with hands that had sutured both skin and silence. Yuko, now carrying the authority of a woman who had taught others, looked at her companions and said, “Perhaps the most important thing we were given in captivity was not food or bed, but a different way of seeing another human being.”

“Soap,” May said, and all of them laughed despite themselves. Soap, a small rectangular bar of lavender-scented kindness, had been their first proof that the enemy considered them worthy.

“What did you do after you left?” Aiko asked, and the answers unfurled: marriages, hospitals, missions, quiet lives of tending and teaching. Some said they hid their time in America, speaking only to the ones who had become confidants. Others said they had made peace and tried to teach a new generation that an enemy could be made into a neighbor with patience.

Yuko pulled out the little hidden notebook she had kept during the war—pages yellowing at the edges, the ink smudged in places where rain had leaked through a tent. She read a short entry aloud: “They treated him as a life to be saved. I do not know yet if this makes me a traitor or a visionary. I only know that I learned to save life in a way that no policy could define.”

At the end of the reunion, old grief and careful joy braided into something like hope. They all carried scars; each scar was a story. Some of the stories were quiet acts of repentance—nurses who later traveled to provinces where Japanese soldiers had brought suffering and offered care to the descendants of victims. Others were loud, political acts—testimonies to a nation slowly reorienting itself in a world that had become smaller and more connected than the myths of empire had allowed.

Years later, Yuko would be asked by a journalist what had broken her. She thought of the operating room, the surgeon’s simple words, the tiny human kindnesses and the smell of soap. “We were broken,” she said, “not by blows but by mercy. Mercy does not disarm a person’s body; it disarms their certainties. That is the hardest thing to bear and, in a strange way, the most precious.”

In the end, the story of the twenty-seven nurses was not a neat parable of conversion or betrayal. It was messy and human. Some stayed rigid in old loyalties. Some changed and adapted and married into lives they could never have imagined. A few could not live with the fractures. Most, however, found ways to reconcile what they had learned with what they had lost. Their experience taught generations of nurses and doctors in postwar Japan better techniques and a new ethic—one that placed individual life at the center of professional duty.

The world they returned to after the war was also learning to be human to its enemies. Old alliances were rebuilt and new ones formed. The soldiers who had once been enemies found themselves decades later in meetings and committees and exchange programs where the same hands that had once grasped rifles now shook in fellowship.

On an autumn morning when Yuko visited a clinic she had helped organize in a shattered neighborhood, an American doctor she had known in the camp—taller now, hair thinner—entered with a delegation from a medical exchange. He recognized her and for a long moment they simply looked at each other like old colleagues who had shared the most contained, intimate of theatres.

“You saved my captain,” he said, and there was no judgment in his voice, only a memory that refused to be reduced to rhetoric.

“You kept him alive,” Yuko answered. “You kept many alive.”

They stood together on a rooftop with a view of the city. Children chased a ball on a field below, and beyond that the harbor’s water flashed like a memory. Yuko reached into her pocket and pulled out a small bar of soap wrapped in paper—a souvenir kept all these years. She handed it to the doctor.

“For luck,” she said.

He took the soap like a blessing and for a moment the two of them held a fragile peace between their hands. They both understood, without the need for grand speeches, that what mattered most was not the politics of the war or the historical judgments that would be rendered in books and lectures. It was the small, stubborn choice to treat a person as a person in the face of instructions that might have told you otherwise.

On the wall of the clinic, Yuko later hung a small framed quotation: “To heal is to remember the humanity in another.” Under it she placed a photograph—faded, black-and-white—of a surgeon and a nurse in an operating room, gloves stained with blood, faces intent. For years afterward, students would sit under that quotation and learn how to operate and how to choose mercy. The clinic became a place where the wounds of the body were tended and, quietly, the wounds of the memory were given a different kind of salve.

When the old nurses gathered in Kyoto for that reunion, someone proposed a simple toast. They lifted small glasses of tea and said, in a chorus that trembled with the weight of memory, “For the lives we saved and the lives we could have saved had the world been kinder sooner.”

And they poured the tea into their lips, tasted it, and knew that their lives—complicated, compromised, redeemed in parts—had become a testament. The enemy had not been crushed by tanks or by rhetoric but by a continuum of ordinary, human actions: a steady hand in surgery, a bar of soap, clean sheets, a bowl of rice passed across a counter. Those acts had unmoored hatred and opened the possibility that compassion, like a small flame, could survive even in the blast-shadow of war.

At the end of her days, Yuko often walked along the harbor that had first greeted her with sun and bewilderment. She would watch the ships and think of the strange pilgrimages of people and the small mercies that had defined so much of her life. Once, when asked what she feared the most, she said, “I fear forgetting how easy it is to be cruel and how cheap it is to dehumanize. But I fear more forgetting how powerful it is to resist that by being kind. The rest—politics, borders, histories—they shift. But the act of saving a life is simple and eternal.”

When she died, some of those who would come to her funeral had been American colleagues who had once sat beside her in an operating theatre, hands steady against life and death. They walked up the aisle and placed a pale bar of soap on her coffin. It seemed to everyone there both an odd gesture and perfectly fitting.

The soap dissolved years before, but what it represented did not. It lingered in the hands that healed and in the minds that taught, a tiny emblem of a belief that had been hard-won: that even in war’s cruel architecture, a single medical act—an insistence on saving a life, regardless of uniform—could break a person’s certainty enough to let compassion in.

Perhaps that was the true victory—small, quiet, far from the triumphant bells of history. A life saved, a prejudice softened, a hand reached across a surgical table. In the long tail of war, those were the things that, when multiplied quietly and steadily, built a new world.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load