He started with small goals. Make the computer talk to him properly. Make it handle tasks the way he wanted. Make it feel less like a locked classroom and more like a workshop.

From scratch.

In C and assembly.

At night, after classes. Between coffee refills. While Helsinki glowed pale and persistent outside the window.

He did not announce it to the world. He did not pitch it to investors. He did not imagine keynote stages or corporate logos.

He imagined himself using it.

That was enough.

The Post

On August 25, Linus did something that, at the time, felt ordinary.

He posted to comp.os.minix.

The message was casual. Almost apologetic.

“I’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones.”

There was no manifesto. No demand. No declaration of rebellion.

Just an invitation.

“If you want to use it, here it is. If you can make it better, please do.”

The internet of 1991 was not the internet of today. It was slow. Fragmented. Mostly academic. Mostly invisible.

But it had one quality that mattered more than speed or scale.

It had people who liked to help.

At first, only a handful noticed.

They downloaded the code. They squinted at it. They poked it with digital sticks.

By September, the system could boot. Barely. It could run a shell. Perform basic operations. Ten thousand lines of code and a stubborn belief that this could be useful.

10,239 lines.

That number would later become a legend, not because it was impressive, but because of what followed it.

Linus did not protect the code. He did not watermark it. He did not sell it.

He left it open.

Wide open.

The Era of Locks

To understand why this mattered, you have to remember the world of software in 1991.

Code was treasure. Corporations guarded it like vaults. Licenses were expensive. Reverse engineering was frowned upon, sometimes punished. The belief was simple and nearly universal.

Quality requires control.

Control requires ownership.

Ownership requires secrecy.

Microsoft, Apple, IBM. They built towers with locked doors and sold keys at premium prices. This model worked. It made fortunes. It shaped the industry.

The idea that thousands of unpaid volunteers could collaborate on something as complex as an operating system felt naive. Dangerous. Almost laughable.

Who would coordinate them?

Who would decide what mattered?

Who would stop chaos?

Linux had no marketing department to answer those questions.

It had a mailing list.

And a rule that sounded reckless.

Anyone could contribute.

The Accidental Community

The first contributors were students, hobbyists, researchers. People who scratched the same itch Linus had scratched.

They found bugs. They fixed them.

They added support for new hardware. They improved performance. They argued. They apologized. They argued again.

They sent patches.

Linus read them.

If the code was good, he merged it.

If it wasn’t, he said so. Sometimes bluntly. Sometimes with humor sharp enough to leave a mark.

This was not democracy. It was meritocracy.

Not political merit. Technical merit.

The code either worked better or it didn’t.

In 1992, Linus made a decision that locked the future in place.

He licensed Linux under the GNU General Public License.

The GPL was not just a legal document. It was a philosophical line in the sand.

Anyone could use Linux. Anyone could modify it. Anyone could distribute it.

But if you improved it, you had to share those improvements.

Forever.

No company could take Linux, lock it up, and sell it back to the world.

Linux would remain free, not as in price, but as in freedom.

That single decision transformed a clever project into a living organism.

Learning to Run

By the mid-1990s, something curious happened.

The internet began to grow teeth.

Websites multiplied. Email exploded. =” centers sprouted like industrial forests.

Companies needed servers. Reliable ones. Cheap ones. Flexible ones.

Linux did not have a sales team.

It had stability.

It did not have glossy brochures.

It had uptime.

It did not require per-seat licenses.

It required curiosity.

Linux became the quiet choice. The engineer’s choice. The system that worked without demanding attention.

Dot-com startups ran on it because they had no money.

Established companies adopted it because it refused to crash at 3 a.m.

Banks trusted it. Universities relied on it. Internet service providers built on it.

Linux did not dominate by conquering. It dominated by being there when things needed to work.

The Phone in Your Pocket

For years, Linux lived mostly in places ordinary people never saw.

Server rooms. Research labs. Supercomputers humming behind locked doors.

Then, in 2008, a company best known for search did something interesting.

Google released Android.

Android was not Linux in name, but it was Linux in spirit and structure. Built on the Linux kernel, wrapped in layers of user-friendly design.

Suddenly, Linux escaped the server room.

It moved into pockets.

Billions of them.

Phones in markets, villages, megacities. Devices that never booted into a terminal window, never showed a penguin mascot, never whispered the word “Linux.”

But it was there. Scheduling tasks. Managing memory. Talking to hardware.

Invisible.

Effective.

Scale Without Ownership

Today, the numbers sound fictional.

Over 96 percent of the world’s top web servers run Linux.

All 500 of the fastest supercomputers use it.

More than three billion Android devices depend on it.

Amazon Web Services. Google Cloud. Microsoft Azure. Mostly Linux.

NASA’s Mars rovers. The International Space Station. SpaceX rockets. Linux.

The Linux kernel now contains more than 27 million lines of code.

More than 19,000 developers from over 1,400 companies have contributed.

It is the largest collaborative project in human history.

And no one owns it.

That last part remains the strangest.

The Philosophy Under the Code

Linux succeeded not just because it was technically sound, but because it broke assumptions.

Before Linux, complexity was thought to require hierarchy.

Linux proved complexity could thrive under shared stewardship.

Before Linux, volunteers were seen as unreliable.

Linux proved volunteers could outperform paid teams when aligned by purpose.

Before Linux, secrecy was equated with quality.

Linux proved transparency could be a force multiplier.

Thousands of eyes do not dilute responsibility. They sharpen it.

Bugs do not hide. They are hunted.

Ideas do not stagnate. They evolve.

This philosophy spilled outward.

Apache became the backbone of the web.

Python reshaped programming culture.

Firefox challenged browser monopolies.

Wikipedia replaced encyclopedias with collaboration.

Open access reshaped science.

Creative Commons reshaped art.

Hardware designs opened up.

The idea that value could be built together, without ownership fencing it off, began to feel less radical and more obvious.

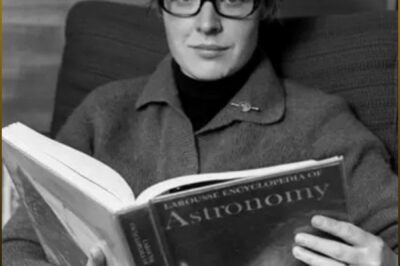

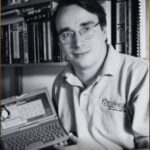

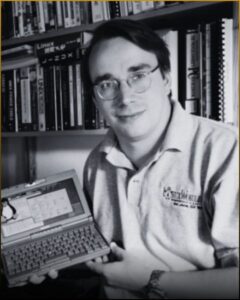

Linus, the Unlikely Symbol

Linus Torvalds never became a tech tycoon.

He never tried.

He works for the Linux Foundation, coordinating development. He earns a comfortable salary. He lives a relatively quiet life.

He remains famously direct. Sometimes abrasive. Uninterested in corporate theater.

He still reviews code.

He still decides what goes in and what stays out.

His leadership style has been studied in business schools that once would have dismissed Linux entirely.

Decentralize authority.

Centralize standards.

Reward merit.

Avoid unnecessary meetings.

Let people do good work and get out of their way.

It is not glamorous leadership.

It is effective.

The Quiet Power

Linux does not advertise.

It does not interrupt your videos.

It does not demand brand loyalty.

It sits beneath things.

It carries weight without asking for credit.

Every Google search. Every streamed song. Every cloud backup. Every online transaction.

Somewhere, Linux is involved.

It does not care if you know.

It was never built to be seen.

From Hobby to Habitat

What began as 10,239 lines of code became a digital habitat.

A place where people from different countries, companies, and cultures could work together without asking permission.

A place where improvement was shared by default.

A place where success did not require exclusion.

Linux did not just change software.

It changed expectations.

It taught the world that collaboration at scale is not chaos.

It is choreography.

It showed that generosity can be structural, not sentimental.

That giving things away does not weaken them.

It strengthens them.

The Sentence That Missed Everything

Looking back, the most famous line in Linux history still feels almost funny.

“Just a hobby, won’t be big.”

It missed everything.

And yet, it captured something essential.

Linux was never built to be big.

It was built to be useful.

Bigness followed usefulness the way gravity follows mass.

Not planned.

Not forced.

Inevitable.

The Ending That Isn’t One

There is no final chapter to Linux.

It updates. It adapts. It continues.

New devices. New architectures. New contributors.

The codebase grows. Shrinks. Refactors itself.

Somewhere, right now, a student is annoyed at their computer.

They open a file.

They read the code.

They change something.

They send a patch.

And the system breathes again.

All because, in 1991, a Finnish student decided his hobby might help someone else.

It did.

Billions of them.

Linux did not just power the modern world.

It quietly redefined how the world could be built.

Together.

Freely.

Without asking permission.

And it all started with a modest post, a small download, and a belief that sharing was not a loss.

It was the point.

News

She kept finding women in laboratory photographs from the 1800s. Then she read the published papers—and every single woman had vanished. Someone had erased them from history.

That night, back in her small apartment, she wrote the question again at the top of a fresh page: Were…

He called his wife ‘the most beautiful animal I own’ on live TV. She stood up, said ‘I have to leave,’ and walked off—while millions watched. That was 1972, and we’re still talking about it.

A small ripple of laughter moved through the audience. Not because it was funny, but because that was what audiences…

She discovered that breast milk changes its formula based on whether the baby is a boy or girl. Then she found something even more shocking: the baby’s spit tells the mother’s body what medicine to make.

For decades, science had treated breast milk like gasoline. A delivery system for calories, fat, protein. Simple fuel for a…

The bill said $0. She thought it was a mistake. Then she realized someone had finally seen her as human.

The Bill That Said Zero The bill said $0. For a long second, the woman at table seven thought the…

He stole her invention and told the judge no woman could design something so complex. She walked into court with 4 years of evidence—and destroyed him.

While other girls asked for dolls or ribbons, Margaret wanted a jackknife. A gimlet. Bits of scrap wood. She liked…

🚨UPDATED WITH TODAY’S SHOCKING ESCALATION: A Single Impeachment Move in Washington Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm No One Saw Coming

A Single Impeachment Move Ignites a Science-Vs-Power Firestorm in Washington Updated with today’s escalation, the showdown over HHS Secretary Robert…

End of content

No more pages to load