“My father,” Thomas explained in halting German. “Like him.” He looked at the sleeping man as though he wished the man could wake and tell him how things had been, before war reshaped every name and memory.

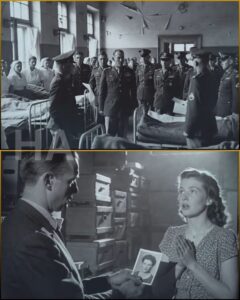

That night the hospital hummed with conversation. The Americans kept returning with crates—bandages, antibiotics, coal for the furnace—and the nurses’ hands were steady but raw with disbelief. For weeks they had rationed kindness as one might ration heat; now warmth arrived in boxes stamped with foreign markings. People whispered, half grateful and half terrified, as if kindness might be another trick.

In the days that followed, Thomas became a frequent presence. He carried small things—tea packets wrapped in waxed paper, a box of soap, gum that tasted like sunlight—and he moved among the cots like a man who had been taught to see the person beneath a uniform before seeing the uniform at all. He spoke little; when he did, his voice had a softness that surprised Elsa.

“I was told to hate people like you,” he said once as they sat on the scuffed bench by the window, folding gowns. His fingers worked the fabric while he looked at her, not at his hands. Snowflakes scrawled themselves slowly down the glass.

Elsa kept folding. “We were told to hate,” she said. Her voice was small and even. “To be afraid that everyone outside our borders was different—worse. It was easier to obey if you believed the fear.”

Thomas made a tiny sound that might have been a laugh. “They told us the same things.” He tapped the photograph in his palm. “But this”—his thumb brushed the woman’s smiling face—“reminded me we were other things too.”

They began to trade stories like they traded bandages and supplies. He told her of his hometown back in Ohio—of summer fairs and an ex-wife who’d left small notes and bigger silences on a kitchen table. She told him of her father’s bakery on Linden Street, of the smell of fresh bread at dawn, the way students used to troop in before class with pockets full of change and too much optimism for the world. When she spoke of the bakery, Elsa’s hands moved as though kneading the air, remembering the dough beneath her palms.

“Did you ever think about the men you fought?” she asked one afternoon while they sat by a patient whose leg had been taken in a bomb crater.

Thomas’s face folded into something solemn. “I think about it when the lights go out,” he admitted. “I replay doors I could have knocked on, orders I could have argued. I was young and good at listening when they said it was for the right reasons. But listening is not knowing.”

Elsa thought of the small things that had mattered during the fighting: a ration of sugar saved and shared, a child’s scraped knee tended while the world burned, the way names blurred into “the enemy” to make the choices easier. “We all listened,” she said. “We were taught stories that made murder logical.”

Winter pressed harder on the city. Frost etched itself along the edges of the ward’s ripped curtains. The Americans arranged coal and blankets; the furnace, with its stubborn fitful flames, made the ward smell faintly of hot iron and promise. For the first time in a long while, the nurses slept through the night without waking to the sound of distant artillery.

One February morning, a rumor swept the ward. Thomas would be reassigned in a week. Movement sounded like good news and like loss; Elsa found both sitting at the same table in her chest. A small panic, private and unreasonable, rose in her.

“Don’t go,” Greta said bluntly one evening, arms crossed, an open bandage in her lap. Greta had never softened so quickly for anyone, not until Thomas appeared in the doorway with a tray of tea for the staff. “People like you leave and the kindness leaves with them.” Her voice had the brittle edge of someone who had lost too much to hope.

Thomas smiled a little. “Maybe the kindness won’t leave,” he said. “Maybe it changes who keeps it.”

“What if it’s only a stopgap?” Elsa asked. “What if next week someone else comes and we’re back where we started?”

“You’ll still be here,” Thomas said simply. “Doing what you do.”

The day before he left, Elsa found him in the storage room. He was packing his duffel with the same care he had shown a dying man’s hand: slowly, reverently, as if each item deserved a goodbye.

“I wanted to thank you,” Elsa said before she could stop herself. The words felt clumsy, inadequate, but they were all she had. “For being human here. For not seeing us as a thing.”

“You don’t have to thank me,” he replied, as though the thought never crossed his mind. Then he hesitated, reached into his breast pocket, and drew out the creased photograph. He pushed it toward her with a steadiness she had not expected.

“For you,” he said. “I want you to have it.”

Elsa’s breath caught. “Why would I—why would you give me this?”

He swallowed. “Because I’ve been keeping the past in my pocket like a stone, and it weighs me down. It reminds me of what I had and what I lost, and it has stopped me from stepping forward. You… you know about loss. You know about carrying things that are gone.”

She looked at the woman’s face in the photograph and felt an ache that had nothing to do with who the woman had been. It had everything to do with what the gesture meant: the handing over of a memory without bitterness, the offering of a space in her life for someone else’s sorrow. “I will keep it safe,” Elsa promised, and slipped the picture into the inner pocket of her coat like a talisman.

Thomas left at dawn, his silhouette swallowed by a gray morning. He turned once to wave—a small, hesitant motion—and the Jeep slipped away, windshield frosted with a road that had to be traveled. The ward seemed to expel a breath it hadn’t known it held.

In the months that followed, the Americans’ presence thinned. Local doctors came back, then administrators, then the slow, stubborn reweaving of ordinary life. The bakery on Linden Street reopened in a new form with fewer staff and a tin sign. Elsa returned there for a morning, tasting bread that was both familiar and new; the dough remembered hands that had been different, but the warmth was the same.

Greta teased her once—half-accusing, half-humored—about keeping a stranger’s photograph in her pocket. “You’re keeping the ghost of a woman who never met you,” she laughed, but her smile softened. Elsa only said, “She reminded him that people had names.”

Years unrolled in a way that heals with small, even stitches. Elsa married, though not the way she had once imagined; the bakery’s owner, a quiet widower who had a laugh like the peal of a bell, offered companionship that was steady as a hearth. They had a daughter named Anna, who insisted on calling the red-haired soldier “the helpful giant” in bedtime stories. Elsa told the story of Thomas mostly in fragments—never the full chronicle; some memories were owned and some were offered like careful relics.

The photograph stayed in a wooden box on Elsa’s mantle. It was not exactly a shrine, nor a shrineless thing. It was a reminder that people could change direction, that a life’s burden might be surrendered, and that a single act of trust could ripple.

On a summer afternoon many years later, when the streets were lined with trees grown taller than the ruined chimneys that had once scarred the skyline, a letter arrived from a place she did not know. The handwriting was unfamiliar, the stamp foreign. Elsa unfolded the paper with the same cautious excitement one uses to open a gift-wrapped secret.

Thomas had found a small job in a clinic in a neighboring town. He wrote of patients who smelled of coal and new paint, of a woman he had married—a nurse, he said, with a laugh that pulled in the corners like a map. He wrote he had never stopped thinking of the kindness he had found in a ruined ward and that sometimes, when the clinic grew quiet and the snow fell, he would take the photograph out and remember the woman who had held it as if it were a seed.

Elsa read the letter with a private kind of joy, one that did not dissolve the years nor cancel the grief. She folded it back into its envelope and placed it into the box with the photograph. The box felt heavier now but in a way that suggested fullness rather than weight. She found herself smiling at a memory that was not a wound.

When she died—peacefully, in a bed that faced the quiet garden—her daughter and grandchildren gathered around and found the little wooden box. Anna, now grown, took the photograph into her hand and learned the story properly for the first time: about a man who had been told to hate and chose to care instead; about a nurse who kept a stranger’s past in her pocket; about coal and bread and the small mercies of hot tea.

At Elsa’s funeral, in a room warmed by remembered laughter and newly lit candles, Anna read aloud Thomas’s letter into a hush that felt like the world agreeing to listen. She finished and set the photograph on the casket as if to say that small things matter—one soldier’s photograph, one woman’s willingness to keep it, one nurse’s patient life lived afterward.

Later, Anna placed the photograph on her own mantel. When friends asked, she would say simply, “It’s a reminder.” Then she would tell them a shorter version of the story: how a man who had been taught to hate learned another way; how a nurse who had been taught to fear received a gift of letting go; how the city’s broken bones had been stitched back together with the ordinary thread of everyday kindness.

“You were told to hate him, weren’t you?” a neighbor once asked across a garden wall, thinking of the old stories and the long lives that changed them.

Elsa—who had been a child then and the neighbor’s voice now belonged to someone else—would have replied the same as her daughter. “Yes. We were told many things. But most important was that we learned how to change our minds.”

And that, in a city that had been rebuilt and renamed and reflowered, is what survived: not the banners and the orders, but the small, stubborn human decisions that say, quietly, I will be kind.

News

STEPHEN COLBERT NAMES 25 HOLLYWOOD FIGURES IN A ‘SPECIAL INDICTMENT REPORT’ — A WEEKEND BOMB THAT SHOOK AMERICA.”

The 14-Minute Broadcast That Exploded Across the Nation It was supposed to be an ordinary weekend.A quiet Saturday night, a…

On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does not simply revisit the story of Virginia Giuffre. It tears apart the entire network of power that once fought to erase that truth from history.

“On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does…

THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE OF VIRGINIA GIUFFRE

“THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE…

They tried to bury her. She left a bomb behind.o press tour. No staged interviews. Just 400 sealed pages… and the names no one else dared to print. Virginia Giuffre — the survivor, the fighter, the woman whose truth once disrupted palaces, gyms, and studios.

Now, even after her death, Virginia Giuffre’s 400-page memoir is set to reveal the hidden battles, the names, and the…

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed before the world finally uncovered the truth..

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed…

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway I was paying for.

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway…

End of content

No more pages to load