Rick’s chest hitched with the confusion of a man whose script had failed.

“What do you mean?” Tanya whispered, clutching the granite counter I had installed because she once said how much the house needed “modern touches.” She had loved the kitchen when she was a child, until she grew into a woman who treated things as props for her life.

I told them. I told them everything I had done in three days: closed the accounts, moved the assets, opened a new secure vault of a bank a town over, printed off every single statement I could find. I told them I had done this while they were shopping for leather seat colors they could never afford if not for my money.

Silence followed my sentence like a physical thing. Tanya’s lips moved but no sound came out. Rick’s hand landed on the table and the vibration rattled the remaining dishes in the cabinet. He tried anger. He tried threat. He tried to sound wounded.

“You live under our roof, Evelyn.” His voice had the brittle quality of a man who had run out of reasons. “You are an elderly woman with health issues. We sacrifice for you. We manage your life. You can’t do this. You’ll ruin us. We have investments, debts — Rick’s partners are expecting payments today. We have a lifestyle.”

“You moved in four years ago because you were evicted for nonpayment of rent,” I said. “You promised it was temporary. You came because you’d lost everything. You are guests. This house is mine, in my name, Arthur’s and my hands laid these bricks forty years ago.”

Tanya’s shoulders shook. She reached toward me as if to touch, but it was only a gesture. “How can you be so cruel?” she said. Her practiced tears shone new on her cheeks. “We’re family, Mom. We love you. We were only managing things for you. Why would you do this now?”

If this was love, I thought, then hate is a safer thing.

I did not stay to argue. I left them in the kitchen, two wounded actors yelling at one another as the curtain fell. I went upstairs to my bedroom, locked the door, and pushed the old oak dresser against it. My heart pounded like a war drum within my chest. I had to remind myself of each step that brought me here, because this was not a sudden betrayal but a slow, corrosive erosion — like the frog in warm water.

It had started soon after Arthur died. The grief had hit me like actual weight — a dull, grey cloak I had to drag through the rooms. On an evening I could not bear the silence, Tanya had called, voice breaking as if she, too, were one of the mourners. Rick had lost his job, their landlord was evicting them, could they come home? Would I take them in?

Of course I did. The whole world had narrowed to the small comforts of being needed. Those first months (honeymoon months, I now see) were filled with mowing, cooking, watching movies. Rick mowed our lawn; Tanya made Sunday dinners. I breathed easier, thinking my prayers had been answered and my loneliness cured.

Then the requests began to tilt into demands, gratitude into expectation. Bills were “temporary,” car repairs “urgent.” Rick suggested putting his name on my account “to take the stress off me.” He sounded like he cared. He sounded like a son.

So I signed. I handed the keys to the kingdom to people I loved and trusted.

And then the mask slipped.

They began to gaslight me. My glasses would go missing; Rick would smile with affection and suggest I was “forgetting things.” He would find them in the refrigerator, or the medicine cabinet. “See?” he’d say, pitying. “Maybe you should talk to Doctor Eris.”

Doctor Eris was everything the name suggested: a man far too eager to write prescriptions and too cheap with empathy. When he offered pills that made the edges of my thoughts soft and manageable, Tanya would hand them to me with a tray of herbal tea. “It’ll help you sleep,” she said. “You’re wound thin.”

They were remodeling the house “to increase property value.” The basement theater was mine in name only. The wine cellar was for them. They brought in a security system that felt designed to keep me in rather than protect me from the world.

The first time I noticed money missing was the day the bank card declined at an ATM. I had gone to buy a birthday card for my granddaughter Mia — a brilliant creature studying law in Boston who Tanya had told me was too busy to visit. When the machine flashed “insufficient funds,” I thought it was a glitch. Inside, a woman named Sarah — a personal banker who had known Arthur for years — pulled up my file and the color drained from her face.

She clicked. $42. That was all that remained, while transfers had been going out for months: Caribbean boat rentals, bespoke suits, casinos, lease payments for a Porsche — a slaughter of forty thousand here, twelve thousand there — and monthly siphons to accounts I did not recognize. I sat there, chest pinching, the world tilting as if I were walking on a ship at sea.

They told me I was confused. They told me I was forgetting. Sarah took my hand. “You’re not confused,” she said. “You’re being exploited.”

That day I devised a plan. If I froze the accounts with the police, Tanya and Rick would be told and would fabricate permission. If I did nothing, the money would be gone. So I opened a new account in a bank a town over, moved everything I could quietly, and walked out with stacks of statements. I sat on a park bench opposite my own house and watched them like beasts feasting. Rick laughed on the porch. Tanya accepted a delivery of designer bags. They looked like vultures coated in luxury.

I went back, put on the old role — apologetic, confused, sweet. They packed my bag for me with relief and glee and eagerness. “Give them space,” Tanya said. “We need to have a little party.”

A cab took me to a motel with flickering neon. For three nights I sat on a lumpy mattress with those bank statements spread on the bed like sacred text. I highlighted every fraudulent transaction in yellow. The total ripped out my throat: nearly a quarter of a million dollars missing. I called Mia.

“Grandma?” she said, voice startlingly like Arthur’s when he’d call late. “Are you all right?”

“Tanya’s lied,” I told her. The confession was an anchor. She sobbed once, then stopped. “I’ll come,” she said. “Get me a plane. I’ll be there in two days. Don’t go back alone.”

So that’s how the scene in the kitchen came to be. For three days I let them think I was gone. I sat quietly and let the plan unfurl. I played the fool who returns early, to catch them mid-feast with their hands still sticky with the jam.

I listened while they argued below my bedroom door. I listened to the scuffle and the threats and the occasional whisper that sounded like hatred. They tried the door once or twice, whispering awful words. The night I did not sleep, I clutched the phone and watched the snow mound around my windows like a white wall of time.

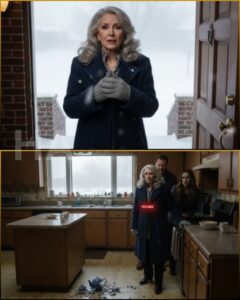

Dawn came crisp and cruel. The street was bright and blinding with snow. I looked out and saw a police cruiser arriving. A sleek black sedan pulled into my unplowed driveway. When I opened the front door, Mia burst into me like a blast of cold, clean air. She folded herself into my shoulders, crying into my coat. Behind her was a uniformed officer and a man in a suit whose whole manner said “law firm,” which Mia had.

We walked into the kitchen where Rick and Tanya sat, hungover and pale. Rick’s chair clattered back as he stood, feigning strength. There were mouths full of coffee and that horrible taste of arrogance.

“What is this?” he demanded. “Evelyn, did you call the cops on your family? Are you having another episode?”

Mia stepped forward like a steel blade. “I am Mia Vance,” she said. “I represent Evelyn Moore. This is a notice of immediate eviction and a temporary restraining order.”

Tanya looked at her daughter as if she were seeing a ghost. “Mia, what — you can’t do this. You can’t represent her against us. She’s sick. She doesn’t know what she’s doing.”

Mia dropped a file onto the granite: bank statements, emails, pictures, forms. “I have proof of financial fraud,” she said. “I have evidence of elder abuse, of attempts to have her declared incompetent, of forgery. You two are under criminal investigation. You will vacate the premises in thirty minutes. Do not test me.”

The transformation in Rick was almost pathetic. The bluster drained out of him like air from a balloon. He started to whistle a new tune: “It was a misunderstanding. It was an investment plan. We were going to pay it back.”

“You can save it for the judge,” the officer said, and the words were heavier than handcuffs. They had thirty minutes. They packed like thieves — clothes heaped into garbage bags, small keepsakes shoved into boxes. Tanya paused at the door and looked at me. Her eyes were empty. “You’re going to die alone,” she spat. “Don’t come to my funeral.”

“Goodbye, Tanya,” I said, and it felt like cutting a rope that had been pulling at me for too long.

When the door slammed behind them I expected silence to fall like a tombstone. Instead a warmth came in, like the first soft breath of spring. It was a small thing, but it was light.

Mia stayed for two weeks. We scrubbed the house until my hands were raw; we painted the guest room a bright yellow because darkness had lived there for too long; we cooked meals that made us laugh until our stomachs hurt. We went to the bank and tied up my assets so snugly that not even the memory of Rick’s fingers could reach them. I learned how to set two-factor authentication with Mia’s help and to use a phone app that told me every debit as it happened. It felt like learning to hold onto myself again.

The trial — such as it was — happened slowly. Rick and Tanya tried every story: “She gifted it,” “She signed willingly,” “She’s being manipulated.” They filed forms that smelled like desperation and cunning. They had friends who could be bought with threats of exposure. But a paper trail is a funny thing; it is stubbornly truthful. The bank had records of transfers. The accountants were unimpressed by tears. The prosecutors were quiet and efficient.

In the end, they took a plea deal to avoid a long, humiliating trial. No one who reads plea deal language will exult in justice, but their deal came with consequences: felony records, orders of restitution, the slow, grinding work of paying back what they had stolen. They avoided prison — a mercy I would have refused if I could have given my money and taken their jail time in return. The system is imperfect. Still, they were marked. They lost their social life, their friends, their comfortable myths of themselves. Most of all, they lost each other.

Life after that was not the same as life before. I have less money than I did, yes. But I have my license to be myself back. I am seventy-three years old and utterly, wonderfully alive in a way I had not been for years.

Spring came late that year. The snow melted to reveal the black earth of the garden, the places where Arthur and I planted bulbs every season. On my knees in the dirt, fingers as cold as when I first learned sutures in the hospital, I planted tulips. I felt the soil press into my calluses and thought of how resistant life is. You press seeds into compressed earth and you trust, and then you wait.

Mia calls every Sunday. We go to the lawyer for updates together. We write letters to the court together when necessary. She became part daughter, part guardian, part friend. She is fierce and proud and, sometimes, infuriatingly young. But she is also tender. Once, when she thought I was asleep on the couch, she sat in the doorway and told me about a case she had won at school. I woke and watched her and felt something like awe. “You saved me,” I said.

“You saved yourself,” she corrected, with the simple conviction of a woman who had learned to stand up for what she loved. “But you saved me, too. You opened my eyes.”

There are days I miss what was lost. The money will never come back in full. There are practical things I do without now — a new roof waits, a car that will be bought later. The house, though smaller in my budget, is mine. I sleep without pills more often. I read late into the night again. I practice piano in the mornings when the light is right. I volunteer down at the clinic twice a week, stitching up what life hands me, and I find it humbling and restorative to be useful again. It is good to be needed for reasons beyond the balance of a bank account.

Sometimes, in a quiet hour, I think about forgiveness. Tanya called me once six months after they left. I almost didn’t pick up. Her voice was thin and full of apologies I had heard before in different shapes. “Mom, I’m sorry,” she said. “We were messed up. We… I don’t know how to fix it.”

I listened. Her apology was not a bridge; it was a leaf blown in from a street. “I don’t want your apology to fix what you broke,” I said. “I want you to help pay what you stole. I want you to learn how to be honest. If that ever happens, maybe then we can talk.”

She hung up. It was not a malicious cut; it was medicine.

If I had to name the hardest lesson, it would be this: blood does not make a contract. A mother’s love can be weaponized if it is unconditional and unexamined. I used to think that sacrifice was the highest form of love. I have learned that boundaries are love’s backbone. Saying no, protecting yourself, insisting on dignity — these are also acts of love, perhaps the most selfish but also the most vital.

Sometimes people ask me if I regret. The answer is complicated. I regret the loss of money and the time taken from me by fear and legal maneuvers. I regret that Arthur is not here to see how stubborn I can be. But do I regret shutting the accounts? No. Do I regret the lie I told about visiting Ruth? No. Both were necessary. To survive, I had to be cleverer than the predators under my roof.

One afternoon, two springs after the storm, I found myself sitting on the back stoop as the tulips opened in a careless parade of reds and pinks. The sun warmed my face. A neighbor passed by with an aging golden retriever that still believed in the magic of squirrels. The neighbor — a woman named Helen whose late husband had been a mechanic down the block — waved. “You doing all right?” she asked.

I laughed. “I’m planting tulips and plotting my vengeance,” I said, because humor is the best armor.

She smiled. “You look good for a woman with vengeance plans. You owe a lot to your holiday bulbs.”

“Every spring gives the world a little back,” I said. “And I guess I’ve been given a second one.”

Helen nodded, the kind of small, human understanding that costs nothing and gives much. She planted a new friend in an old life: a neighbor who would check in, bring casseroles at odd hours, and complain about noise in a way that was familiar and welcome.

At night, I often sit in my kitchen and look at the spot where the teapot lay that terrible day. I have a reproduction now — a humble thing with the same blue irises painted by someone else’s steady hand. It doesn’t replace the original, but it is a promise: that fragility can be built again.

“Grandma,” Mia said one Sunday after we planted a row of bulbs together, “you taught me how to read the fine print.”

I kissed her knuckles as she scrubbed dirt from her nails. Her face was freckled and sharp and the same shade of stubborn I’d always seen in Tanya when she was a child, the way she’d stand before a skinned knee and insist on bravery with a face that was almost a laugh.

“You taught yourself,” I said. “But I’m glad you were there.”

She looked at me with that fierce, appointed tenderness of hers. “You deserved better,” she said.

“No,” I answered. “We learned we deserve better.”

There are mornings now when I rise and realize that I do not begin with small, secret dread. I do not reach for the phone expecting a debt call or a pretended emergency. I have quiet, which once was terrifying and now is a clean space to create from. I have people who respect me for my mind and my stubbornness, not for the bank balance that used to call them home.

If you ask me whether I would do it all again — the hiding, the motel, the fear — I would say yes. Not because I love battle, but because I love the life I fought for after. I love the taste of my coffee in the morning, the clumsy cat who now sleeps at the foot of my bed, the letters Mia writes and the lunches I make and the x-rays I read at the clinic and the way the garden smells in May.

On a small, ordinary note, once in a while I treat myself to buying a card and sending it to Mia in Boston with scribbles in the margins about tulips and weather and how stubbornly brave she is. She writes back in long, legalese-free letters about cases and friends and sometimes, in a corner, a doodle of a tulip or a dog.

I am Evelyn Moore. I am seventy-three. I have less money than I did, but I have enough. I have my house. I have my dignity. I have Mia, who calls every Sunday and sometimes during the week with a brief, “How are you?” that is really an armor-bearer.

There are seasons I will always remember: a winter that nearly killed me, a spring that made me plant tulips with hands that had been taught to stitch human flesh into wholeness, a summer in which I walked the lakefront with new steady steps. The storm came and went. It took my security, shook it like loose change, and left me to collect what mattered.

When strangers come to my yard and ask about my bulbs, I tell them, with the same plainness I used when confronting two grown people who thought themselves entitled to everything, that bulbs need a little darkness to grow. “Plant them deep,” I tell them. “Cover them and wait. They’ll come up when they’re ready.”

Sometimes people look at me, confused by the metaphor. Sometimes they understand. Either way, I plant. I wait. And come spring, the world blooms again.

News

The Twins Separated at Auction… When They Reunited, One Was a Mistress

ELI CARTER HARGROVE Beloved Son Beloved. Son. Two words that now tasted like a lie. “What’s your name?” the billionaire…

The Beautiful Slave Who Married Both the Colonel and His Wife – No One at the Plantation Understood

Isaiah held a bucket with wilted carnations like he’d been sent on an errand by someone who didn’t notice winter….

The White Mistress Who Had Her Slave’s Baby… And Stole His Entire Fortune

His eyes were huge. Not just scared. Certain. Elliot’s guard stepped forward. “Hey, kid, this area is—” “Wait.” Elliot’s voice…

The Sick Slave Girl Sold for Two Coins — But Her Final Words Haunted the Plantation Forever

Words. Loved beyond words. Ethan wanted to laugh at the cruelty of it. He had buried his son with words…

In 1847, a Widow Chose Her Tallest Slave for Her Five Daughters… to Create a New Bloodline

Thin as a thread. “Da… ddy…” The billionaire’s face went pale in a way money couldn’t fix. He jerked back…

The master of Mississippi always chose the weakest slave to fight — but that day, he chose wrong

The boy stood a few steps away, half-hidden behind a leaning headstone like it was a shield. He couldn’t have…

End of content

No more pages to load