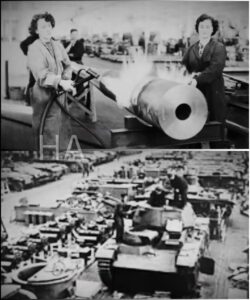

How One Factory Girl’s Idea Helped Turn the Tide of War

1

At 7:10 a.m., the Lake City Ordnance Plant was already awake in the way living things wake during wartime, not gently, but violently.

The stamping presses slammed brass into shape with a force that rattled the ribs. Annealing furnaces exhaled waves of heat that bent the air. Conveyor belts rattled and hissed like long mechanical snakes. The smell was copper, oil, sweat, and ozone, all mixed together until it no longer smelled like anything at all, just urgency.

Nineteen-year-old Evelyn Carter pushed her cart of unfinished cartridge casings across the concrete floor, careful not to look up at the ceiling fans that barely moved the air. She had learned quickly that thinking too much about the heat made it worse.

She had been at Lake City for twelve weeks.

That made her new. That made her invisible.

Most of the women around her had been there since 1942, when the war stopped being something heard on the radio and started being something measured in quotas. They wore cotton headscarves darkened with sweat, sleeves rolled past the elbow, movements precise from repetition. They did not waste motion. They did not waste words.

Evelyn liked them, even when they scared her a little.

“Line four’s behind again,” someone muttered as Evelyn passed.

“Always is,” another answered.

No one raised their voice. Sound disappeared inside the factory. You learned to talk with glances, with nods, with timing.

Evelyn reached line four and began unloading her cart. Six women stood shoulder to shoulder at the feeder table, feeding brass casings into narrow alignment tracks that guided them toward charging and crimping.

Pick. Place. Slide.

Pick. Place. Slide.

The motion never changed.

The plant wanted thirty thousand casings fed per hour on this line. On good days, they reached twenty-three thousand. On bad days, less.

Those missing seven thousand did not stay numbers. They became reports. They became red pencil marks in Washington. They became short letters from soldiers complaining about ammunition rationing, letters that were posted on the bulletin board near the break room.

“We’re firing faster than you can make them,” one Marine sergeant had written. “Send more.”

Evelyn had read it three times.

At 7:26 a.m., a guide rail snapped loose.

The sound was sharp, wrong. Metal clattered across the floor. Casings spilled like coins. The red warning lamp flashed overhead.

“Stop!” the foreman shouted.

The line went silent, an eerie absence that made the heat suddenly unbearable. Mechanics hurried in. Supervisors checked clipboards. The women stepped back, rubbing their wrists, wiping sweat from their faces.

Evelyn knelt to gather the spilled casings.

That was when she noticed the hands.

Not the individual hands, but the pattern.

Six pairs of hands moved in looping arcs, wrists rotating in the same direction, shoulders repeating the same tight circle. The movement was not linear. It was circular, disguised as a line.

Pick. Place. Slide.

Pick. Place. Slide.

It reminded her of something.

She frowned, holding a casing loosely between her fingers. The memory hovered just out of reach. A museum trip with her father, years ago. Something that spun to go faster instead of forcing itself to stop and start.

“Evelyn.”

She looked up. One of the older women, Ruth, nodded toward her cart.

“Go on. We’ve got this.”

Evelyn stood slowly, pushing the cart away, but the thought followed her.

A wheel.

The idea felt absurd. She was not an engineer. She had finished high school and gone straight to factory work when her brother shipped out. She earned eighty cents an hour and kept her head down.

And yet the thought would not leave.

What if the problem was not speed?

What if it was motion?

2

By 8:00 a.m., the day shift had fully settled in. The plant whistle screamed, metal on metal, echoing across the Missouri fields.

Production charts were updated. The deficit was small on paper, tens of thousands of rounds short. But Evelyn had learned how numbers multiplied. Tens of thousands became millions. Millions became stalled offensives.

She pushed her cart past line six, watching the belts rattle under the weight of half-finished rounds. Somewhere over the Pacific, men were firing machine guns faster than Lake City could replenish them.

At 8:25, a lieutenant from the Ordnance Department addressed the floor.

“We are behind,” he said bluntly. “Consumption rates have increased by nearly thirty percent across all commands. If output does not rise by autumn, operations will suffer.”

No one reacted. They already knew.

Evelyn listened, heart pounding, her mind no longer on the speech but on the image forming behind her eyes.

A rotating platform.

Multiple stations sharing the load.

Continuous motion.

Not hands forcing brass forward, but a system that carried it.

At 9:11, she found herself back beside line four, watching the feeders again. The rhythm was precise, but strained. Fatigue showed in the slight tremble of wrists, the micro-pauses between motions.

A loop disguised as a line.

Her breath caught.

It was clear now. So clear it frightened her.

She stepped away before she could talk herself out of it.

3

The scrap bin near the east wall was filled with forgotten things: bent brackets, broken pallets, discarded bearings. Evelyn reached in, her fingers brushing cold metal.

A bearing ring.

Her heart jumped.

She dragged it free, wiping grease onto her apron. It was heavy, solid, circular. A wheel needed a heart.

She ducked behind stacked crates and laid the bearing on the concrete floor. Around it, she arranged wooden slats into rough shapes, testing rotation, imagining casings resting in shallow slots.

“This is insane,” she whispered.

But she kept going.

At 9:31, a mechanic stepped out of the maintenance shed and froze.

“What are you doing, kid?”

Evelyn startled, words tumbling out of her.

“I’m sorry, I just… the feeders. They move in circles already. What if the machine did it instead? Like… like that old gun. The Gatling.”

The mechanic frowned, then squatted beside her.

“What problem are you trying to solve?”

“Throughput,” she said instantly. “We’re losing time.”

He nodded slowly.

“That we are.”

He didn’t laugh.

At 9:42, Evelyn borrowed a dull pencil and sketched furiously at the drafting table. A central ring. Peripheral slots. A linkage to the existing motor.

She did the math roughly. Nine rotations per minute. A thousand casings per rotation. Her hands shook.

At 9:50, the foreman found her.

She braced for anger.

Instead, he stared at the sketch for a long moment.

“We’ll test it at lunch,” he said finally. “Three minutes.”

4

The first test was a disaster.

The wooden wheel wobbled violently. Casings flew. One skittered across the floor like a spinning coin.

Laughter rippled through the crowd, tired but not cruel.

“Time,” the foreman said.

Then the mechanic stepped forward.

“One more.”

They slowed the rotation. Adjusted the tension.

Three casings dropped cleanly.

Silence followed.

Not success. But possibility.

Later, Ruth approached Evelyn quietly.

“You see that dent?” she said, pointing to a casing rim. “Fatigue. To metal. To people.”

She nodded toward the wheel.

“Anything that eases that is worth trying.”

Evelyn swallowed hard.

5

That night, steel replaced wood.

Sparks flew as the night crew welded a proper wheel, heavy and overbuilt. Rubber lined the slots. A weighted rim stabilized the rotation.

Evelyn watched from the shadows, barely breathing.

At 8:06 p.m., the wheel turned smoothly for the first time.

Nineteen casings fed cleanly.

At 8:09, the engineer did the math.

“At scale,” he murmured, “this doubles output.”

No one spoke.

6

The next morning, the wheel was bolted into line two.

“If it fails, we shut it down,” the foreman said. “If it works, you’ll feel it.”

At 7:13 a.m., the counter passed seven hundred casings per minute.

At 7:44, it crossed eighty thousand per hour.

The plant fell into stunned silence.

The superintendent authorized immediate replication.

No speeches. No applause.

Just numbers.

7

Within weeks, Lake City’s output surged past two billion rounds per month.

The rotating feeder spread to other plants. Minor variations appeared. No one remembered Evelyn’s name at first.

She didn’t mind.

Months later, a letter arrived from her brother.

“We never ran dry,” he wrote. “Whatever you’re doing back home, keep doing it.”

Evelyn folded the letter carefully and tucked it into her apron.

The factory roared on.

And the wheel kept turning.

News

🚨 HOT – FINAL MINUTES THAT BROKE THE INTERNET: Joe Rogan Saves One Last Surprise — and Country Music History Is Made LIVE On Air

A Full-Circle Moment for the Broken and the Brave: Jelly Roll’s Emotional Invitation to the Grand Ole Opry on Joe…

THE MUSICAL BOMB EXPLODES: TAYLOR AND Travis Kelce DECIDE TO SPEND 11 MILLION DOLLARS TO LAUNCH THE BIGGEST MUSIC SHOW IN AMERICA CALLED ‘MUSIC AND JUSTICE’

THE MUSICAL BOMB EXPLODES: How “Music and Justice” Became the Most Unprecedented Stage in America THE MUSICAL BOMB EXPLODES: TAYLOR…

🚨 BREAKING “LOYALTY TEST” SHOCKWAVE: One Sentence From AOC Ignites a Constitutional Crisis No One Prepared For

AOC’S SHOCK DECLARATION TRIGGERS EMERGENCY DISQUALIFICATION AND A HISTORIC PURGE OF CONGRESS Emergency Disqualification has hit Congress with a force…

🔥 KENNEDY READS ILHAN OMAR’S FULL “RESUME” LIVE — CNN PANEL FROZEN FOR 11 HEART-STOPPING SECONDS – Inside the Fictional Television Showdown Where Senator Kennedy Read Ilhan Omar’s ‘Resume’ and Silenced an Entire CNN Panel

The fictional broadcast began like any other primetime political segment, with polished voices from the CNN studio warming up the…

The Feral Inbred Cannibals of Appalachia — The Macabre Story of the Godfrey Cousins

Bootprints led toward a creek. Smaller footprints appeared beside them, barefoot, more than one set. Bone fragments lay near an…

Inbred Cannibals You Didn’t Know Existed — The Macabre Legend of the Broussard Family

Generations of isolation had folded the family inward. Marriages between cousins and siblings were not spoken of as unusual. They…

End of content

No more pages to load