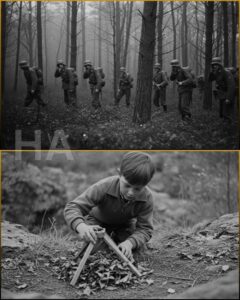

What he discovered later to be physics—the convergence of photons into heat—felt like fate. In the months that followed he turned the broken lens into an obsession because people who are stripped of everything else cartography their curiosity into the small things they can control. He learned to measure focal length by trial and error, to carve a steady cradle from a fallen branch, to brace his forearm against the log in the way a marksman learns to still his breath. He practiced with leaves and bark, with curls of paper and splintered wood, timing seconds and learning the sinews of light.

Trains did not bother to be gentle. They lumbered through the valley as if the whole eastern front depended on their indifferent wheels. They carried tanks and shells and blankets and fuel—the last of which smelled faintly and chemically even when it did not leak in the broad daylight. The tanks’ seams were sometimes sloppily welded; their relief valves, designed to spare pressure, leaked a scent like a promise of ignition. Yseph, who had learned to notice the smallest betrayals of metal and seam, noticed these details and was not merely curious. He had a ledger in his head of the things the occupiers moved across his country, and hate had learned to read like a practical ledger.

His first strike—if the word strike was not too martial for something that began with a boy and a borrowed lens—was a clumsy, accidental thing on a gray Tuesday in October of 1942. He had been sitting on the ridge at Dead Man’s Curve, 60 meters above the tracks, palms numbed by frost. He had chosen the spot because the world angulated at that point in such a way that the sun came from behind him, and the curve slowed the train, and the valve on the tankers would lift its head just long enough. The train that day crawled like a beast, engine groaning, smoke spitting. He had steadied the lens and felt the absurd hush in his own chest, the silence before something that might make a noise that a boy’s heart is not meant to hear.

Three seconds.

He told himself it was three seconds because that is what it had felt like. The beam caught the valve and he saw a heat shimmer, that air-wave that rises off the asphalt in summer. He did not place his intention in the world as a prayer; he placed it as a calculation, as one might aim a stone. The vapor above the valve ignited—not a small flame, but the kind of bloom that surprises the sky. The tanker roof folded inward like a tin can pressed by a giant’s thumb and the train became a geyser of orange that lit the valley like a cathedral exploding. He dropped the lens, rolled backward into the ditch, and vomited his breakfast in a skinny river the color of iron.

The immediacy of the blast had a clarity to it that would never leave him. He heard the soldiers shout and the crack of ammunition catching fire in other cars. He saw the guards incinerated before their rifles could lift, saw metal twitch like a body in rigor. He crawled through mud and roots until he could stand to look again, and in that hour the valley was lit and small, an ugliness that belonged to other people but which now also belonged, intimately, to him.

For a while the Germans did not look for the child. They were, in their efficient cruelty, methodical. They brought men in to analyze fragments, to search for the fingerprints of explosives. Reinhardt—a man with the thin face of someone who thought too much about columns and ledger lines—came first. He walked the tracks with gloved hands and a notebook, and where others expected fury, he offered deduction. He scrawled the word “anomaly” and ordered tree lines cut back, patrols doubled. But they were looking in the wrong way; they wanted someone with dynamite, someone who made a messy, chemical mess. They did not look for glass.

Yseph learned to be smarter after that. He learned that greed and patterns could be used by smaller creatures. He trained through the frost and the thaw. He carved a log to hold the lens, learned to mount it, to cradle the tiny needle of light against the tremor of his own blood. He read, surreptitiously, from a ruined schoolbook in a language with German words that meant less than the diagrams that taught collimation and focal planes. He studied sun angles the way other children learned ghosts and saints. He learned to be patient with weather, with the way the atmosphere breathes like a sleeping animal, picking days where the air sat like glass on a valley.

His triumphs grew as the stakes grew. On a spring afternoon he found a cliff that looked out over the Naru bridge. At three hundred meters the air itself conspired against him with moisture, pollen, and dust. For forty seconds—forty threshold seconds—he kept the coin of light on the valve of the tanker. When the seal finally gave, the vapor met the beam and a contained blast buckled the trusses like bone. The bridge sagged and gave and the tanks, with everything that fed their bellies, plunged in a fumy rain into the river below. For the first time in many months, the valley smelled not only of fear but of possibility.

But it was in that same moment of possibility that Reinhardt had decided the village would pay for silence with flesh. He stood on the town hall steps and announced—through a language that was not his—an impossible calculus: ten men would die for the crime that the saboteur did not confess. They hanged neighbors in front of their families. The baker’s body swung like a metronome in the square. Yseph watched the rope take the men he had known and felt the rope tighten around his own throat.

He knew, clearly then, that heroism was not an uncomplicated thing. He had set his hand to the world, and the world had responded in such a way that the cost registered not in tanks downed or bridges ruined but in the faces of small boys and women who had given him bread. He retreated to the familiar dark of the cottage and did what he could not stop doing: he thought like a craftsman, not like a martyr. The calculus of war was obscene, but he could not unmake the arithmetic any more than he could unmake the beam of light. If the Germans would trade ten lives for one, he could trade for a steeper price. He decided to keep going.

What he did not expect was Reinhardt’s answer: the mind can fasten itself to an idea like a vice. Reinhardt studied lines on a map and realized what those lines suggested—attack times synchronized with the arc of the sun. He began to watch not just the tracks but the ridges, the way light glinted off a hidden lens. He set snipers in trees and inspectors with instruments; he waited like a spider in a web. On the summer solstice he planned to watch the sun and wait for the glint.

Yseph did not know Reinhardt was waiting when he climbed the opposite ridge on the longest day of the year. The sun was a mercy and a weapon, and at four hundred and fifty meters the margin for error was a single shaking breath. He wedged the lens and watched the valves pass like a heartbeat. For three seconds—it is always three for Yseph in his memory—the beam found the third tanker. Reinhardt saw that degree of unnatural bright and signaled his marksman. Bullets cracked around the stone where Yseph crouched. A bullet splintered a rock inches from his face, sending shards into his eyes.

He flinched and the lens wobbled. He rolled. The beam, however, had already done its work. The vapor above the third tanker was hair-fine but ready; it met the converging photons and detonated. The entire convoy answered with a roar that emptied the forest of birds. Metal folded, rails buckled, and three tankers—three of them—turned into a single, cathedral-sized fireball. The blast blew Reinhardt off his feet. It shattered glass and scattered the nearest hunters with honeycombs of heat. The valley became a breathing wound.

Yseph ran until he could not. He ran with the twofold weight of triumph and culpability pressing his chest. He collapsed into a ditch and smothered his face into his hands for a long time, counting the shards of his life like prayer beads. He was alive. The train was gone. But somewhere two dozen men and the logistics of a front were counting losses in arithmetic that did not name the names of the dead as people, only as =”.

What followed was a season of hunting. Reinhardt and his men swept villages and questioned children and burned houses where suspicion hung heaviest. They interrogated with methodical cruelty, with the coldness of insurance adjusters. They looked for glass and for burns and for the telltale tremor of one who had seen the flame and wished they had not. The snow came and then the year wore on and Reinhardt, like many men packed with his sort of small certainties, was reassigned. He left a file on a desk and a string of open wounds through families who had been punished for a phantom.

Yseph never struck again. The lens was too heavy for the kind of boy he wanted to be, and it was suddenly as ugly as any instrument a human could make. When the occupation ended and the Soviets rolled in, the world shifted with new names and new rulers, and in the spring Awa died in her sleep with a hand that had once steadied him resting on the blanket. Yseph buried the lens in her curled fingers, wrapped in the same rag he had used on the ridges. He did not speak when people asked if he was a hero. He did not know how to be a hero; he only knew how to make something burn.

Time does strange things to people who have been both hunter and hunted. Yseph grew into a man with hands that learned to coax the temperaments of machines rather than to make them obey. He crossed the ocean after the war because borders needed to be crossed and new names needed to be invented. In Detroit he lived a life that looked like any other factory man’s life: a rhythm of machines, three children, a house with a porch that leaned in the same way his grandmother’s had. On paper he was Joseph Kowalski—steady, polite, the sort of man who kept his work gloves in the same drawer and who never spoke of flames.

But some fires are stubborn in how they will not be contained. Fifty years after the first train went up in a ribbon of orange and smoke, Joseph sat in a hospital bed with a young graduate student leaning close and a recorder in his hand. He had agreed, with the weary collusion of an old man who thinks telling the truth might be a small absolution, to tell his story. He told it in short sentences, the way one does when a memory is a brittle plate. He told of the lens and the curve and the bridge and the faces. When he finished, the student—bright-eyed, eager—wrote “senile” in the margin and put the tape in a box with other sound and other ghosts.

The box sat in an archive for decades, scribbled with time and dust until a historian named Dr. Helena Zimmermann found Reinhardt’s file in a basement of military logistics. Reinhardt’s notes were clinical, neat—“anomaly,” the word repeated like a talisman. The records were rigid with the German penchant for numbers, dates, and angles, and they made an odd pattern when placed side by side with Joseph’s voice. Dr. Zimmermann, who had made a profession of listening to things others preferred not to hear, cross-referenced weather logs, train manifests, and the scratchy tape from Detroit. She traced the sunlight out of maps like a seamstress looking for thread.

It took the cold, quiet work of scholarship to place a small, broken lens into the narrative of history. When she published the paper—careful, footnoted, unwilling to over-claim—she did not write of glory. She wrote of consequence. She wrote the boy’s name and then the man’s. She wrote of a valley and of scorched stone that had vitrified in the sun and could not be explained by ordinance. She wrote of the terrible arithmetic of reprisals and how a child’s ingenuity can be both a wedge against empire and a hammer that breaks small lives.

By then Joseph was gone. He had died two weeks after the interview in 1987, a man who never wished to be remembered as monstrous or noble. He had been a man who learned how to make the light do the work of explosives, and whose nights were occupied with faces he could not unlearn. There was no medal on his grave, no public marker in the village; only a small stone and the whisper of a name.

The story—if story can ever be used for history—refuses neat moralization. There is no tidy line between sin and courage when children make war on things that took their families. Yseph had not sought to become a martyr. He sought to avenge, to wrestle agency from the hollow epic of occupation. In doing so he recalculated matter and light, and the world answered with flames. He found that cunning and science, when held in a small hand, are as dangerous as any rifle. He also found, cruelly, that the legalistic mind of an occupying power will always translate acts of desperation into paperwork and reprisals.

A woman who had been a child in the village wrote to Dr. Zimmermann after the paper appeared. She signed her letter with a name Yseph did not know; she described the long winter and the smell that followed the explosions for months and how, for a while, the war had been an abstract machine and then—suddenly—an orange bloom in the valley. “We loved the men who hanged,” she wrote simply. “They baked our bread. We had their children attend our weddings. The rails bringing fuel were a thing that kept the world moving, but when the sky became a furnace we knew it was not only an economic calculation. We became small and cold and hungry and so afraid.”

Her letter asked for something impossible: not forgiveness but understanding. Not absolution but that someone somewhere know that what people do in wartime is often layered in motives that are not clean. It is one thing to kill an empire’s supply line and another to understand the faces that hang for it.

That complexity is, in the end, the humanistic core of Yseph’s story. He had been a child who learned to make sunlight a weapon because the stronger men had taken other weapons away. He had been both the product and the producer of war’s perverse mathematics. He had killed—if the word could not be unmade—and he had mourned those he had not killed but whose lives were undone by the chain reaction of his act. He kept the lens wrapped and buried, as if doing so could bury the calculus too.

Sometimes in the quiet of night he would dream of the burned bridge and then wake and stare at his hands. They were ordinary hands, yellowed with oil and callus, and yet they had once cupped a focus of light as if it were a fragile planet. He could not reconcile those two things. He could only live the rest of his life in the muddy valley between them: the man who mended machines, the boy who made trains a bonfire.

When scholars and small-mouthed history shows later chronicled the phenomenon, they called it the “sun gun,” a name heavy with the curious poetry of cheap engineering. The label is less important than the human residue: the baker who swung on a rope for trains that carried other people’s needs, the grandmother who pulled blankets over a sleeping child’s feet and who died without ever seeing peace, the man who would spend his life on a factory floor mending transmissions for an army that had long since folded, the boy who had learned to count the sun like a clock.

In the summer, when the valley was green and wildflowers forgot their names, you could hike to the ridge where the first scorch marks froze into black stone. The granite there, vitrified in a way not wholly explainable by conventional explosions, held a stubborn testimony. The locals grew used to the story told by the stones: Yseph had been a child who used sunlight as a detonator; he had been a maker of mischief and a figure of ruin. Some called him a hero who dared to make the occupying machine pay a price. Others called him a murderer. Most, when they went home, sat in the dim of their kitchens and thought of the men who hanged in the square, and of the bread their bodies had once shaped, and of the hands on their children’s shoulders that had still trembled after.

The moral of such a memory is not neat; it resists the tidy categories war historians prefer. It is humbling because it refuses to be heroic in the way a weathervane of cause likes to be. Yseph had been both instrument and instrument-wielder, a child and a maker of consequences.

Near the end of his life in America Joseph used to go to a small park on Sunday mornings when the city felt like a village without a rope. He would sit on a bench and watch fathers teach sons to swing a bat, watch kids throw stones into the river with the light reckless and intact. He never told them about the lens. He loved those afternoons because they had smallness to them: a thrown ball, a laugh. In that smallness he believed the only honest redemption was in the everyday acts of care. He would leave the park with his pockets filled with the small understanding that if you could not undo the past you could try—one conversation, one loaf, one mending at a time—to keep yourself from becoming a story that only taught others how to break.

When Dr. Zimmermann published her paper, she did it without fanfare. She put footnotes where others might have put coronations. She did not declare a hero. She declared a fact: there had been a series of saboteur attacks on fuel trains that matched the dates and weather, and a man in Detroit had, in his last voice, told the tape his truth. The world took it in different ways. Postwar resentment and the need for clean narratives made the story convenient to fold into larger myths about the asymmetric genius of desperate people. Veterans of the valley argued in small rooms over whether it was right. Small-town newspapers ran obituaries and genealogies. Families—those who hanged and those who fled—kept living.

Yseph’s life was not redeemed with a monument nor vanquished into shame so absolute that historians must look away. It remained, like all hard stories, a fissure in the face of memory that let weeds grow. The story refuses absolution, but it does not refuse truth. The truth is that sometimes a child will pick up a piece of glass because the world has offered him nothing else, and that physics—an impartial collaborator—will do what physics does. The truth is also that human cost is not a useful metric for history unless it is paired with the recognition that those costs are people’s lives, too complicated and tender for a single sentence.

If you walk now to the ridge and place your palm on the blackened stone, you might find it warm in late sun. You might see the arc of the valley where trains once cut a river of industry. You might notice the smallness of a boy’s footsteps in the dirt if you listen. And then you might walk back into the village, buy a loaf of bread from some baker who had only children and small dreams, and carry it home with the knowledge that war is made of many small acts—some of courage, some of desperation, some of cruelty—and that the human heart learns to live among them not by seeking simple labels but by holding the facts in one hand and, in the other, the small acts of care that might, in low and broken ways, stitch the world back together.

Yseph died like many people do: quietly, with the neighbor’s cat on the windowsill and a slow reading light on a table. He died without expecting to be forgiven for things history would name and without expecting a medal. He had been a boy who learned to turn sun into fire because it was the only means left to him. He had been a man who learned to fix transmissions and to keep his promises small and kind. In the end, the broken lens lay buried under his grandmother’s hand and a stone that bore no inscription, because the story did not fit on a plaque. It fit, instead, in the hard and generous work of remembering.

This is not a story that asks you to choose a side. It asks you to look, carefully, at the faces that war makes: the one who reaches for a tool because everything else has been taken; the one who pays a price for an act he did not commit because the machinery of power demands a sacrifice; the old woman who wraps a rag around a lens without knowing it will be used again. It asks for a kind of compassion that is specific and not sentimental—an obligation to name complexity and to refuse the economy that simplifies people into statistics.

History will keep its lists and its columns, its dates and its strategies. But the ridge remembers the heat in a way paper cannot, and the stone keeps the ghost of a child’s decision in the crystalline scars of its face. The light that once burned the valley is ordinary now, usable for tea and for reading and for the warmth of morning. Sometimes, if you sit very still on a clear day, you can see the way it catches in a pocket of glass—a tiny, perfect world inverted—and wonder at the shapes of choices we make when the world puts us in front of a sun and gives us a lens.

News

STEPHEN COLBERT NAMES 25 HOLLYWOOD FIGURES IN A ‘SPECIAL INDICTMENT REPORT’ — A WEEKEND BOMB THAT SHOOK AMERICA.”

The 14-Minute Broadcast That Exploded Across the Nation It was supposed to be an ordinary weekend.A quiet Saturday night, a…

On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does not simply revisit the story of Virginia Giuffre. It tears apart the entire network of power that once fought to erase that truth from history.

“On November 27, the dark wall shatters into pieces once again. ‘DIRTY MONEY’ — Netflix’s new four-part series — does…

THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE OF VIRGINIA GIUFFRE

“THE ‘KING OF COUNTRY MUSIC’ GEORGE STRAIT LOST CONTROL AS HE CALLED OUT 38 POWERFUL FIGURES CONNECTED TO THE FATE…

They tried to bury her. She left a bomb behind.o press tour. No staged interviews. Just 400 sealed pages… and the names no one else dared to print. Virginia Giuffre — the survivor, the fighter, the woman whose truth once disrupted palaces, gyms, and studios.

Now, even after her death, Virginia Giuffre’s 400-page memoir is set to reveal the hidden battles, the names, and the…

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed before the world finally uncovered the truth..

In 1995, four teenage girls learned they were pregnant. Only weeks later, they vanished without a trace. Twenty years passed…

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway I was paying for.

My sister ordered me to babysit her four children on New Year’s Eve so she could enjoy the holiday getaway…

End of content

No more pages to load